Personnel Psychology

B-

Psychologists can assist organizations at various stages of selecting and assessing employees. They may help identify needed job skills, decide upon selection methods, recruit and evaluate applicants, introduce and train new employees, and appraise their performance. They can also help job seekers. Across four dozen studies, training programs (which teach job-

Matching Interests and Strengths to Work

The best job is one that pays you to do what you love, which may be doing things with your hands, thinking of solutions, expressing yourself creatively, assisting people, being in charge, or working with data. Do what you love and you will love what you do.

A career counseling science aims, first, to assess our differing values, personalities, and, especially, interests, which are remarkably stable (Dik & Rottinghaus, 2013). (Your job may change, but your interests today will likely still be your interests in 10 years.) Second, it aims to alert us to well-

Discovering Your Interests and Strengths

You can use some of the techniques personnel psychologists have developed to identify your own interests and strengths and pinpoint types of work that will likely prove satisfying and successful. Gallup researchers Marcus Buckingham and Donald Clifton (2001) have suggested asking yourself these questions:

What activities give me pleasure? Bringing order out of chaos? Playing host? Helping others? Challenging sloppy thinking?

What activities leave me wondering, “When can I do this again?” rather than, “When will this be over?”

What sorts of challenges do I relish? And which do I dread?

What sorts of tasks do I learn easily? And which do I struggle with?

Some people find themselves in flow—

The U.S. Department of Labor also offers a vocational interest questionnaire via its Occupational Information Network (O*NET). At www.mynextmove.org/

realistic (hands-

on doers), investigative (thinkers),

artistic (creators),

social (helpers, teachers),

enterprising (persuaders, deciders), and

conventional (organizers).

Finally, depending on how much training you indicate being willing to undertake, you will be shown occupations that fit with your interest pattern (selected from a national database of 900+ occupations). A more comprehensive (and fee-

Satisfied and successful people devote far less time to correcting their deficiencies than to accentuating their strengths. Top performers are “rarely well rounded,” Buckingham and Clifton found (p. 26). Instead, they have sharpened their existing skills. Given the persistence of our traits and temperaments, we should focus not on our deficiencies, but rather on identifying and employing our talents. There may be limits to the benefits of assertiveness training if you are extremely shy, of public speaking courses if you tend to be nervous and soft-

Identifying your interests can help you recognize the activities you learn quickly and find absorbing. Knowing your strengths, you can develop them further.

Matching Strengths to Work

As a new AT&T human resources executive, psychologist Mary Tenopyr (1997) was assigned to solve a problem: Customer-

She asked new applicants to respond to various test questions (without as yet making any use of their responses).

She followed up later to assess which of the applicants excelled on the job.

She identified the earlier test questions that best predicted success.

The happy result of her data-

Your strengths are any enduring qualities that can be productively applied. Are you naturally curious? Persuasive? Charming? Persistent? Competitive? Analytical? Empathic? Organized? Articulate? Neat? Mechanical? Any such trait, if matched with suitable work, can function as a strength (Buckingham, 2007).

Buckingham and Clifton (2001) have argued that the first step to a stronger organization is instituting a strengths-

For example, if you were interested in harnessing the strengths needed for success in software development, and you had discovered that your best software developers are analytical, disciplined, and eager to learn, you would focus employment ads less on experience than on the identified strengths. You might ask: “Do you take a logical and systematic approach to problem solving [analytical]? Are you a perfectionist who strives for timely completion of your projects [disciplined]? Do you want to master Java, C++, and Python [eager to learn]?”

Identifying people’s strengths and matching those strengths to work is a first step toward workplace effectiveness. To assess applicants’ strengths and decide who is best suited to the job, personnel managers use various tools. These include ability tests, personality tests, and behavioral observations in “assessment centers” and work situations that test applicants on tasks that mimic the job they seek (Ryan & Ployhart, 2014; Sackett & Lievens, 2008). Some traits predict success in many types of jobs. If you are both conscientious and agreeable, you will likely flourish in many work settings (Cohen et al., 2014; Sackett & Walmsley, 2014).

Do Interviews Predict Performance?

“Interviews are a terrible predictor of performance.”

Laszlo Bock, Google’s Vice President, People Operations, 2007

Many interviewers feel confident of their ability to predict long-

Unstructured Interviews and the Interviewer Illusion

Traditional unstructured interviews can provide a sense of someone’s personality—

Interviewers presume that people are what they seem to be in the interview situation. An unstructured interview may create a false impression of a person’s behavior toward others in different situations. But research reveals that how we behave reflects not only our enduring traits, but also the details of the particular situation (such as wanting to impress in a job interview).

Interviewers’ preconceptions and moods color how they perceive interviewees’ responses (Cable & Gilovich, 1998; Macan & Dipboye, 1994). If interviewers instantly like a person who perhaps is similar to themselves, they may interpret the person’s assertiveness as indicating “confidence” rather than “arrogance.” If told certain applicants have been prescreened, interviewers are disposed to judge them more favorably.

Page B-6Interviewers judge people relative to those interviewed just before and after them (Simonsohn & Gino, 2013). If you are being interviewed for business or medical school, hope for a day when the other interviewees have been weak.

Interviewers more often follow the successful careers of those they have hired than the successful careers of those they have rejected. This missing feedback prevents interviewers from getting a reality check on their hiring ability.

Interviews disclose the interviewee’s good intentions, which are less revealing than habitual behaviors (Ouellette & Wood, 1998). Intentions matter. People can change. But the best predictor of the person we will be is the person we have been. Educational attainments predict job performance partly because people who have shown up for school each day and stayed on task also tend to show up for work and stay on task (Ng & Feldman, 2009). Wherever we go, we take ourselves along.

“Between the idea and reality . . . falls the shadow.”

T. S. Eliot, The Hollow Men, 1925

Hoping to improve prediction and selection, personnel psychologists have put people in simulated work situations, sought information on past performance, aggregated evaluations from multiple interviews, administered tests, and developed job-

Structured Interviews

structured interview interview process that asks the same job-

Unlike casual conversation aimed at getting a feel for someone, structured interviews offer a disciplined method of collecting information. A personnel psychologist may analyze a job, script questions, and train interviewers. The interviewers then ask all applicants the same questions, in the same order, and rate each applicant on established scales.

In an unstructured interview, someone might ask, “How organized are you?” “How well do you get along with people?” or “How do you handle stress?” Street-

By contrast, structured interviews pinpoint strengths (attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, and skills) that distinguish high performers in a particular line of work. The process includes outlining job-

To reduce memory distortions and bias, the interviewer takes notes and makes ratings as the interview proceeds and avoids irrelevant and follow-

A review of 150 findings revealed that structured interviews had double the predictive accuracy of unstructured interviews (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998; Wiesner & Cronshaw, 1988). Structured interviews also reduce bias, such as against overweight applicants (Kutcher & Bragger, 2004).

If, instead, we let our intuitions bias the hiring process, noted writer Malcolm Gladwell (2000, p. 86), then “all we will have done is replace the old-

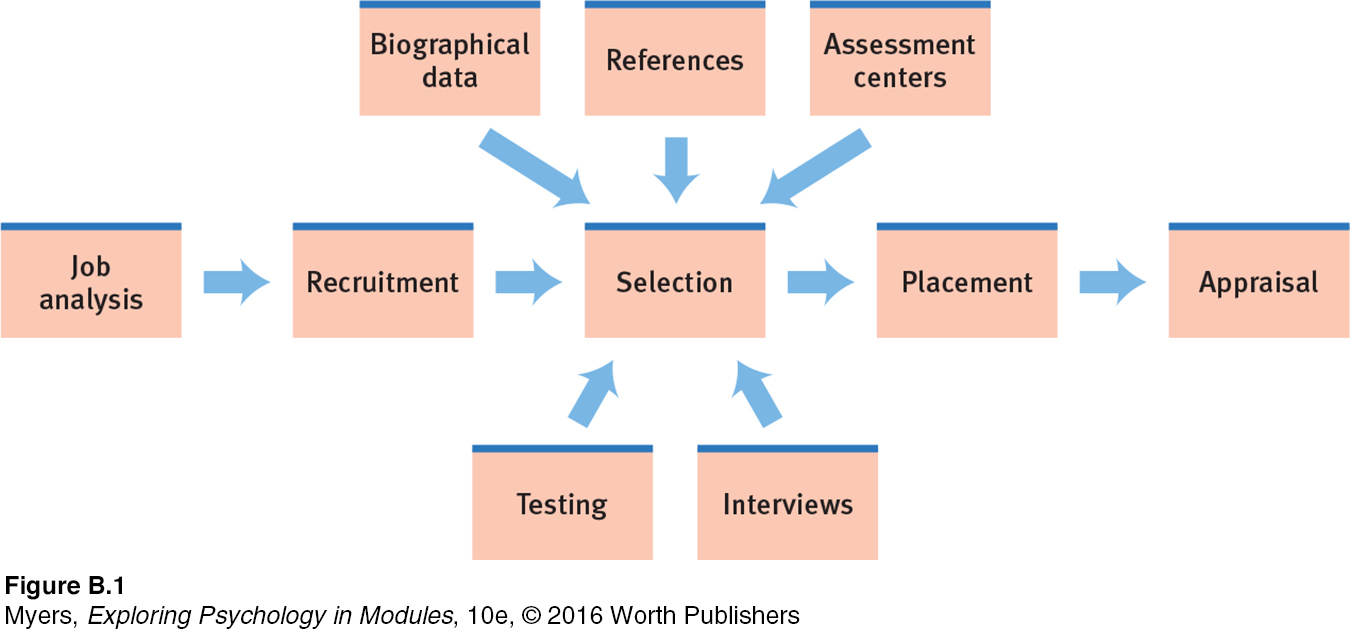

To recap, personnel psychologists help job candidates to assess their own interests and strengths, and they assist organizations in matching employee strengths to appropriate jobs. Personnel psychologists also appraise employees’ performance (FIGURE B.1)—the topic we turn to next.

Appraising Performance

Performance appraisal serves organizational purposes: It helps decide who to retain, how to appropriately reward and pay people, and how to better harness employee strengths, sometimes with job shifts or promotions. Performance appraisal also serves individual purposes: Feedback affirms workers’ strengths and helps motivate needed improvement.

Performance appraisal methods include

checklists on which supervisors simply check specific behaviors that describe the worker (“always attends to customers’ needs,” “takes long breaks”).

graphic rating scales on which a supervisor checks, perhaps on a five-

point scale, how often a worker is dependable, productive, and so forth. behavior rating scales on which a supervisor checks scaled behaviors that describe a worker’s performance. If rating the extent to which a worker “follows procedures,” the supervisor might mark the employee somewhere between “often takes shortcuts” and “always follows established procedures” (Levy, 2003).

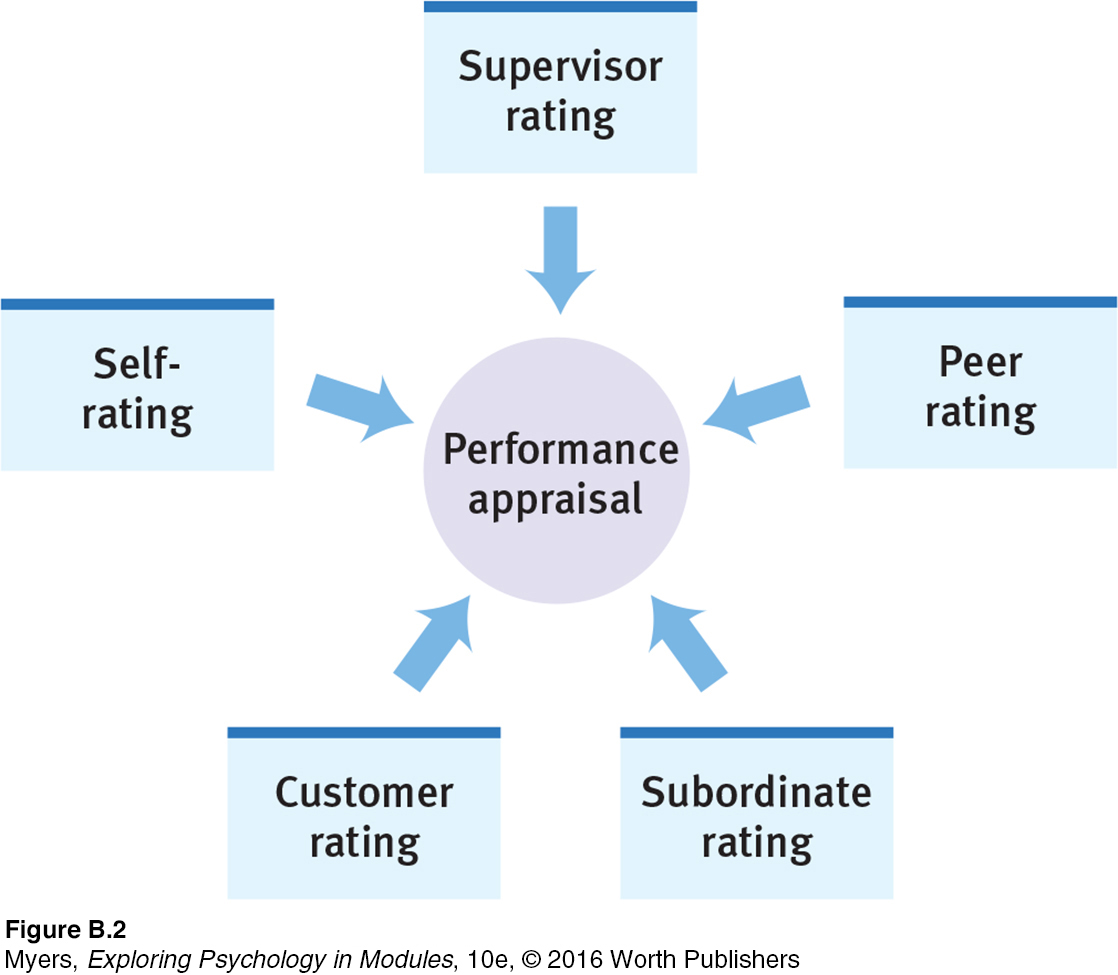

In some organizations, performance feedback comes not only from supervisors but also from all organizational levels. If you join an organization that practices 360-

Performance appraisal, like other social judgments, is vulnerable to bias (-Murphy & Cleveland, 1995). Halo errors occur when one’s overall evaluation of an employee, or of a personal trait such as their friendliness, biases ratings of their specific work-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

A human resources director explains to you that “I don't bother with tests or references. It's all about the interview.” Based on I/O research, what concerns does this raise?