31.1 Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition

31-1 How do arousal, expressive behavior, and cognition interact in emotion?

Not only emotion, but most psychological phenomena (vision, sleep, memory, sex, and so forth) can be approached these three ways—physiologically, behaviorally, and cognitively.

Motivated behavior is often connected to powerful emotions. My [DM’s] own need to belong was unforgettably disrupted one day. I went to a huge store and brought along Peter, my toddler first-born child. As I set Peter down on his feet for a moment so I could do some paperwork, a passerby warned, “You’d better be careful or you’ll lose that boy!” Not more than a few breaths later, I turned and found no Peter beside me.

With mild anxiety, I peered around one end of the customer service counter. No Peter in sight. With slightly more anxiety, I peered around the other end. No Peter there, either. Now, with my heart accelerating, I circled the neighboring counters. Still no Peter anywhere. As anxiety turned to panic, I began racing up and down the store aisles. He was nowhere to be found. The alerted store manager used the public-address system to ask customers to assist in looking for a missing child. Soon after, I passed the customer who had warned me. “I told you that you were going to lose him!” he now scorned. With visions of kidnapping (strangers routinely adored that beautiful child), I braced for the unthinkable possibility that my negligence had caused me to lose what I loved above all else, and that I might have to return home and face my wife without our only child.

Courtesy of David Myers

But then, as I passed the customer service counter yet again, there he was, having been found and returned by some obliging customer. In an instant, the arousal of terror spilled into ecstasy. Clutching my son, with tears suddenly flowing, I found myself unable to speak my thanks and stumbled out of the store awash in grateful joy.

Emotions are subjective. But they are real, says researcher Lisa Feldman Barrett (2012, 2013): “My experience of anger is not an illusion. When I’m angry, I feel angry. That’s real.” Where do our emotions come from? Why do we have them? What are they made of?

Emotions are our body’s adaptive response. They support our survival. When we face challenges, emotions focus our attention and energize our actions (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Our heart races. Our pace quickens. All our senses go on high alert. Receiving unexpected good news, we may find our eyes tearing up. We raise our hands triumphantly. We feel exuberance and a newfound confidence. Yet negative and prolonged emotions can harm our health.

emotion a response of the whole organism, involving (1) physiological arousal, (2) expressive behaviors, and (3) conscious experience.

As my panicked search for Peter illustrates, emotions are a mix of:

bodily arousal (heart pounding).

expressive behaviors (quickened pace).

conscious experience, including thoughts (“Is this a kidnapping?”) and feelings (panic, fear, joy).

The puzzle for psychologists is figuring out how these three pieces fit together. To do that, the first researchers of emotion considered two big questions:

A chicken-and-egg debate: Does your bodily arousal come before or after your emotional feelings? (Did I first notice my racing heart and faster step, and then feel terror about losing Peter? Or did my sense of fear come first, stirring my heart and legs to respond?)

How do thinking (cognition) and feeling interact? Does cognition always come before emotion? (Did I think about a kidnapping threat before I reacted emotionally?)

Historical emotion theories, as well as current research, have sought to answer these questions.

Historical Emotion Theories

The psychological study of emotion began with the first question: How do bodily responses relate to emotions? Two historical theories provided different answers.

Joy expressed According to the James-Lange theory, we don’t just smile because we share our teammates’ joy. We also share the joy because we are smiling with them.

Matt Sullivan/Reuters/Landov

James-Lange theory the theory that our experience of emotion is our awareness of our physiological responses to an emotion-arousing stimulus.

JAMES-LANGE THEORY: AROUSAL COMES BEFORE EMOTION Common sense tells most of us that we cry because we are sad, lash out because we are angry, tremble because we are afraid. First comes conscious awareness, then the feeling. But to pioneering psychologist William James, this commonsense view of emotion had things backward. Rather, “We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble” (1890, p. 1066). To James, emotions result from attention to our bodily activity. James’ idea was also proposed by Danish physiologist Carl Lange, and so is called the James-Lange theory. James and Lange would have guessed that I noticed my racing heart and then, shaking with fright, felt the whoosh of emotion—that my feeling of fear followed my body’s response.

Cannon-Bard theory the theory that an emotion-arousing stimulus simultaneously triggers (1) physiological responses and (2) the subjective experience of emotion.

CANNON-BARD THEORY: AROUSAL AND EMOTION OCCUR SIMULTANEOUSLY Physiologist Walter Cannon (1871-1945) disagreed with the James-Lange theory. Does a racing heart signal fear or anger or love? The body’s responses—heart rate, perspiration, and body temperature—are too similar, and they change too slowly, to cause the different emotions, said Cannon. He, and later another physiologist, Philip Bard, concluded that our bodily responses and experienced emotions occur separately but simultaneously. So, according to the Cannon-Bard theory, my heart began pounding as I experienced fear. The emotion-triggering stimulus traveled to my sympathetic nervous system, causing my body’s arousal. At the same time, it traveled to my brain’s cortex, causing my awareness of my emotion. My pounding heart did not cause my feeling of fear, nor did my feeling of fear cause my pounding heart.

If our bodily responses and emotional experiences occur simultaneously and independently, as the Cannon-Bard theory suggested, then people who suffer spinal cord injuries should not notice a difference in their experience of emotion after the injury. But there are differences, according to one study of 25 World War II soldiers (Hohmann, 1966). Those with lower-spine injuries, who had lost sensation only in their legs, reported little change in their emotions’ intensity. Those with high spinal cord injury, who could feel nothing below the neck, did report changes. Some reactions were much less intense than before the injuries. Anger, one man with a high spinal cord injury confessed, “just doesn’t have the heat to it that it used to. It’s a mental kind of anger.” Other emotions, those expressed mostly in body areas above the neck, were felt more intensely. These men reported increases in weeping, lumps in the throat, and getting choked up when saying good-bye, worshiping, or watching a touching movie. Such evidence has led some researchers to view feelings as “mostly shadows” of our bodily responses and behaviors (Damasio, 2003). Brain activity underlies our emotions and our emotion-fed actions (Davidson & Begley, 2012).

But our emotions also involve cognition (Averill, 1993; Barrett, 2006). Here we arrive at psychology’s second big emotion question: How do thinking and feeling interact? Whether we fear the man behind us on the dark street depends entirely on whether we interpret his actions as threatening or friendly.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

According to the Cannon-Bard theory, (a) our physiological response to a stimulus (for example, a pounding heart), and (b) the emotion we experience (for example, fear) occur EyzGsDe490D04Wlzz8y3ksgMZ4M=

(simultaneously/sequentially). According to the James-Lange theory, (a) and (b) occur a7V8Uz5jhOwIrHUA1B2DlfuZhj4=

(simultaneously/sequentially).

(first the physiological response, and then the experienced emotion)

Schachter-Singer’s Two Factors: Arousal + Label = Emotion

31-2 To experience emotions, must we consciously interpret and label them?

two-factor theory the Schachter-Singer theory that to experience emotion one must (1) be physically aroused and (2) cognitively label the arousal.

The spillover effect Arousal from a soccer match can fuel anger, which can descend into rioting or other violent confrontations.

Oleg Popov/Reuters/Landov

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, see LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation, below.

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, see LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation, below.

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) demonstrated that how we appraise our experiences matters greatly. Our physical reactions and our thoughts (perceptions, memories, and interpretations) together create emotion. In their two-factor theory, emotions have two ingredients: physical arousal and cognitive appraisal. An emotional experience, they argued, requires a conscious interpretation of arousal.

Consider how arousal spills over from one event to the next. Imagine arriving home after an invigorating run and finding a message that you got a longed-for job. With arousal lingering from the run, would you feel more elated than if you received this news after staying awake all night studying?

To explore this spillover effect, Schachter and Singer injected college men with the hormone epinephrine, which triggers feelings of arousal. Picture yourself as a participant: After receiving the injection, you go to a waiting room, where you find yourself with another person (actually an accomplice of the experimenters) who is acting either euphoric or irritated. As you observe this person, you begin to feel your heart race, your body flush, and your breathing become more rapid. If you had been told to expect these effects from the injection, what would you feel? The actual volunteers felt little emotion—because they attributed their arousal to the drug. But if you had been told the injection would produce no effects, what would you feel? Perhaps you would react as another group of participants did. They “caught” the apparent emotion of the other person in the waiting room. They became happy if the accomplice was acting euphoric, and testy if the accomplice was acting irritated.

This discovery—that a stirred-up state can be experienced as one emotion or another, depending on how we interpret and label it—has been replicated in dozens of experiments (Reisenzein, 1983; Sinclair et al., 1994; Zillmann, 1986). As Daniel Gilbert (2006) noted, “Feelings that one interprets as fear in the presence of a sheer drop may be interpreted as lust in the presence of a sheer blouse.”

The point to remember: Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

According to Schachter and Singer, two factors lead to our experience of an emotion: (1) physiological arousal and (2) XkPMXfT7QJJq66nMlxyQ1A==

appraisal.

Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Does Cognition Always Precede Emotion?

But is the heart always subject to the mind? Must we always interpret our arousal before we can experience an emotion? Robert Zajonc (1923–2008) [ZI-yence] didn’t think so. Zajonc (1980, 1984) contended that we actually have many emotional reactions apart from, or even before, our conscious interpretation of a situation. Perhaps you can recall liking something or someone immediately, without knowing why.

For example, when people repeatedly view stimuli flashed too briefly for them to interpret, they come to prefer those stimuli. Unaware of having previously seen them, they nevertheless like them. We have an acutely sensitive automatic radar for emotionally significant information; even a subliminally flashed stimulus can prime us to feel better or worse about a follow-up stimulus (Murphy et al., 1995; Zeelenberg et al., 2006).

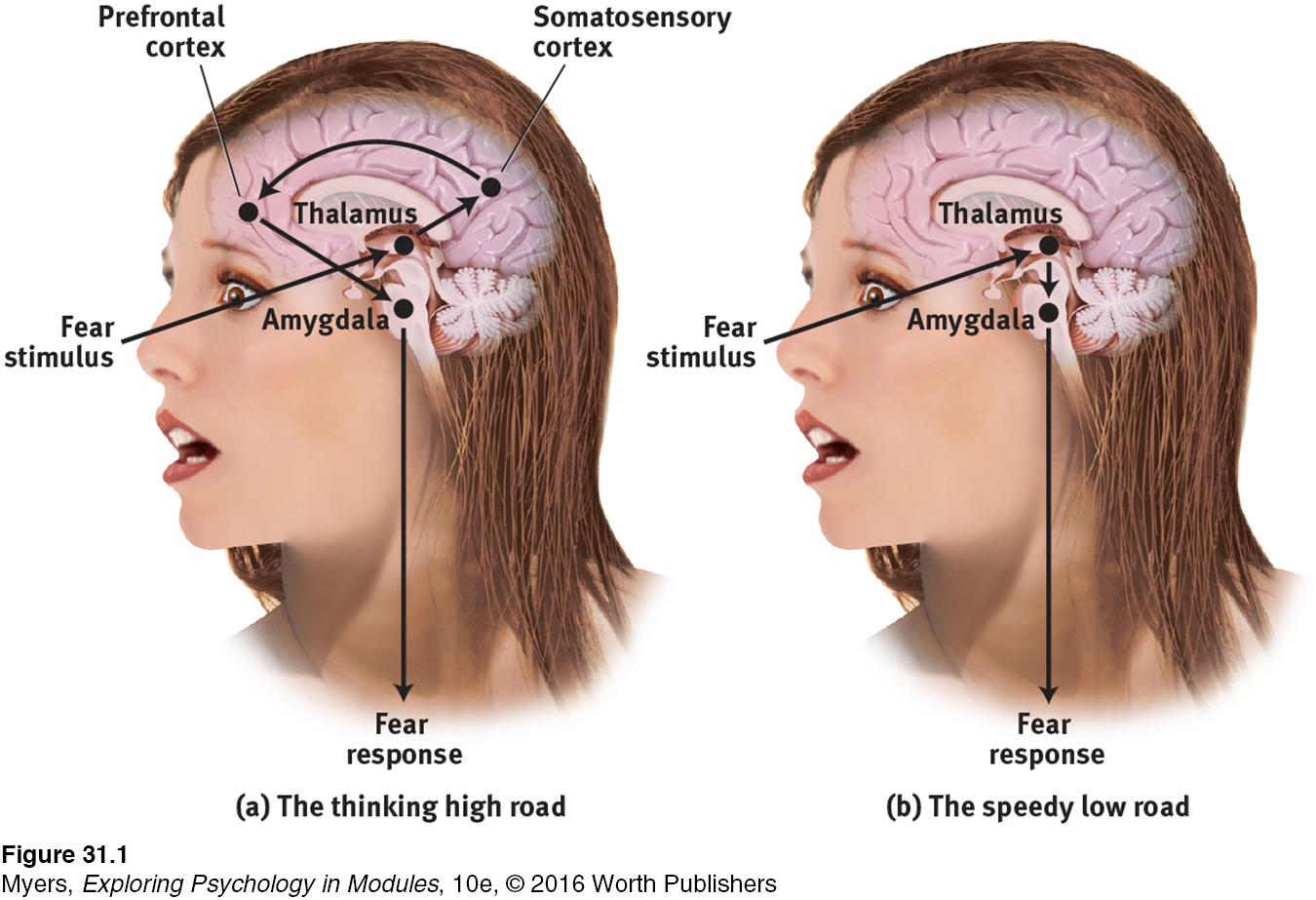

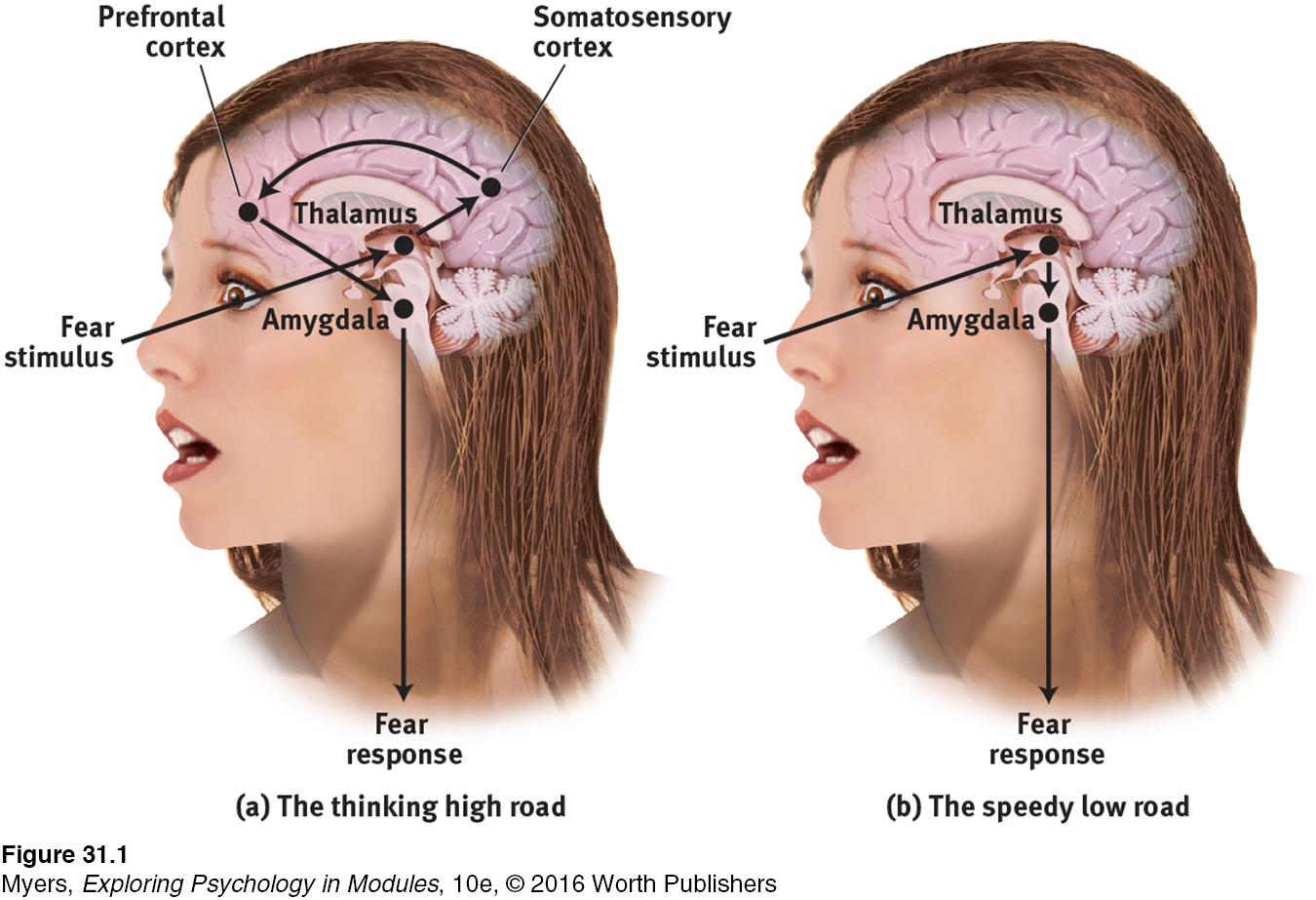

Neuroscientists are charting the neural pathways of emotions (Ochsner et al., 2009). Our emotional responses can follow two different brain pathways. Some emotions (especially more complex feelings like hatred and love) travel a “high road.” A stimulus following this path would travel (by way of the thalamus) to the brain’s cortex (FIGURE 31.1a below). There, it would be analyzed and labeled before the response command is sent out, via the amygdala (an emotion-control center).

But sometimes our emotions (especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears) take what Joseph LeDoux (2002) has called the “low road,” a neural shortcut that bypasses the cortex. Following the low road, a fear-provoking stimulus would travel from the eye or ear (again via the thalamus) directly to the amygdala (FIGURE 31.1b). This shortcut enables our greased-lightning emotional response before our intellect intervenes. Like speedy reflexes (that also operate apart from the brain’s thinking cortex), the amygdala reactions are so fast that we may be unaware of what’s transpired (Dimberg et al., 2000).

The amygdala sends more neural projections up to the cortex than it receives back, which makes it easier for our feelings to hijack our thinking than for our thinking to rule our feelings (LeDoux & Armony, 1999). Thus, in the forest, we can jump at the sound of rustling bushes nearby, leaving it to our cortex to decide later whether the sound was made by a snake or by the wind. Such experiences support Zajonc’s belief that some of our emotional reactions involve no deliberate thinking.

Figure 10.9: FIGURE 31.1 The brain’s pathways for emotions In the two-track brain, sensory input may be routed (a) to the cortex (via the thalamus) for analysis and then transmission to the amygdala; or (b) directly to the amygdala (via the thalamus) for an instant emotional reaction.

Emotion researcher Richard Lazarus (1991, 1998) conceded that our brain processes vast amounts of information without our conscious awareness, and that some emotional responses do not require conscious thinking. Much of our emotional life operates via the automatic, speedy low road. But, he asked, how would we know what we are reacting to if we did not in some way appraise the situation? The appraisal may be effortless and we may not be conscious of it, but it is still a mental function. To know whether a stimulus is good or bad, the brain must have some idea of what it is (Storbeck et al., 2006). Thus, said Lazarus, emotions arise when we appraise an event as harmless or dangerous, whether we truly know it is or not. We appraise the sound of the rustling bushes as the presence of a threat. Later, we realize that it was “just the wind.”

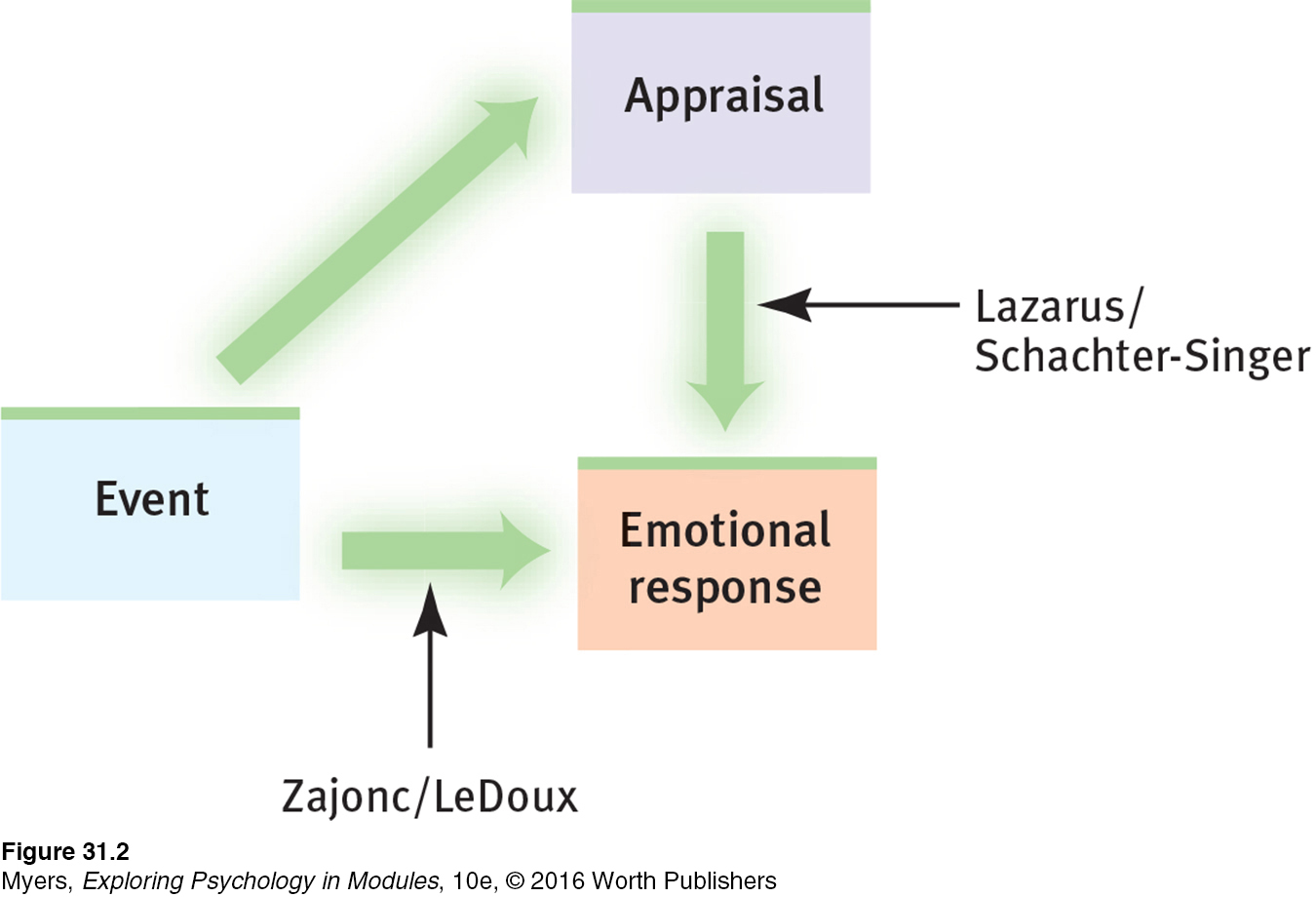

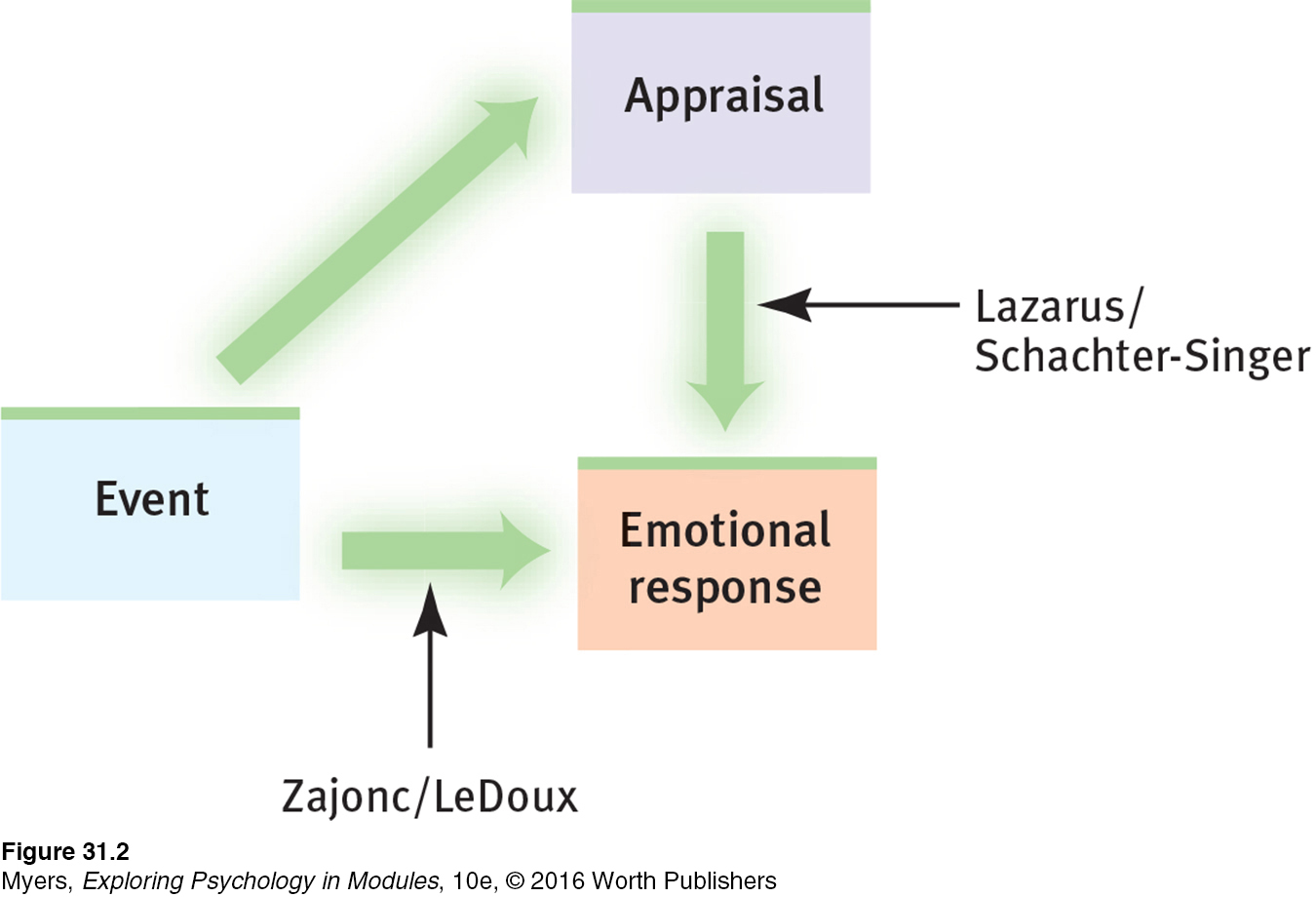

So, as Zajonc and LeDoux have demonstrated, some emotional responses—especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears—involve no conscious thinking (FIGURE 31.2). When I [ND] view a big spider trapped behind glass, I experience fear even though I “know” the spider can’t hurt me. Such responses are difficult to alter by changing our thinking. Within a fraction of a second, we may automatically perceive one person as more likeable or trustworthy than another (Willis & Todorov, 2006). This instant appeal can even influence our political decisions if we vote (as many people do) for a candidate we like over the candidate who expresses positions closer to our own (Westen, 2007).

Figure 10.10: FIGURE 31.2 Two pathways for emotions Zajonc and LeDoux emphasized that some emotional responses are immediate, before any conscious appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized that our appraisal and labeling of events also determine our emotional responses.

But our feelings about politics are also subject to our conscious and unconscious information processing—to our memories, expectations, and interpretations. When we feel emotionally overwhelmed, we can change our interpretations (Gross, 2013). Such reappraisal often reduces distress and the corresponding amygdala response (Buhle et al., 2014; Denny et al., 2015). Highly emotional people are intense partly because of their interpretations. They may personalize events as being somehow directed at them, and they may generalize their experiences by blowing single incidents out of proportion (Larsen & Diener, 1987). Thus, learning to think more positively can help people feel better. Although the emotional low road functions automatically, the thinking high road allows us to retake some control over our emotional life. Together, automatic emotion and conscious thinking weave the fabric of our emotional lives. (TABLE 10.3 summarizes these emotion theories.)

Table 10.2: TABLE 10.3

Summary of Emotion Theories

| Theory |

Explanation of Emotions |

Example |

| James-Lange |

Emotions arise from our awareness of our specific bodily responses to emotion-arousing stimuli. |

We observe our heart racing after a threat and then feel afraid. |

| Cannon-Bard |

Emotion-arousing stimuli trigger our bodily responses and simultaneous subjective experience. |

Our heart races at the same time that we feel afraid. |

| Schachter-Singer |

Our experience of emotion depends on two factors: general arousal and a conscious cognitive label. |

We may interpret our arousal as fear or excitement, depending on the context. |

| Zajonc; LeDoux |

Some embodied responses happen instantly, without conscious appraisal. |

We automatically feel startled by a sound in the forest before labeling it as a threat. |

| Lazarus |

Cognitive appraisal (“Is it dangerous or not?”)—sometimes without our awareness—defines emotion. |

The sound is “just the wind.” |

RETRIEVE IT

Question

pNteiTEGD5Ke53+urWgS4HkP889f89E6vaENuRlvTDBJmJoCt/55OHsDxg3b+Z2PVC2X3Rt9NNsZQmQs1LRdULeojUVo7b31VVQhSXKhQWS+eBM+je/3Y7UnzyJsOXGkDHOdITTonHS5ojWnvgoY8lRg4WlnrBHsRhd7i19aaa3mkDGPEXD3sd9BAhr5JgRROD0f+JosKNQhZjZUxhzrL0RPYqYqTqz5mHB/xpHxfRoWmyPVXSA/QqUwNuPNHTQO5jK5LobTJzlgeUnZeUmV7UPFIQszxLKzlJI46hVtleznaZ906vlUQ0PKsj4yw31CC+tLQA==

ANSWERS: Zajonc and Ledoux suggested that we experience some emotions without any conscious, cognitive appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized the importance of appraisal and cognitive labeling in our experience of emotion.

For a 4-

For a 4-