31.2 Embodied Emotion

Whether you are falling in love or grieving a death, you need little convincing that emotions involve the body. Feeling without a body is like breathing without lungs. Some physical responses are easy to notice. Other emotional responses we experience without awareness. Before examining our physical responses to specific emotions, consider another big question: How many distinct emotions are there?

The Basic Emotions

31-

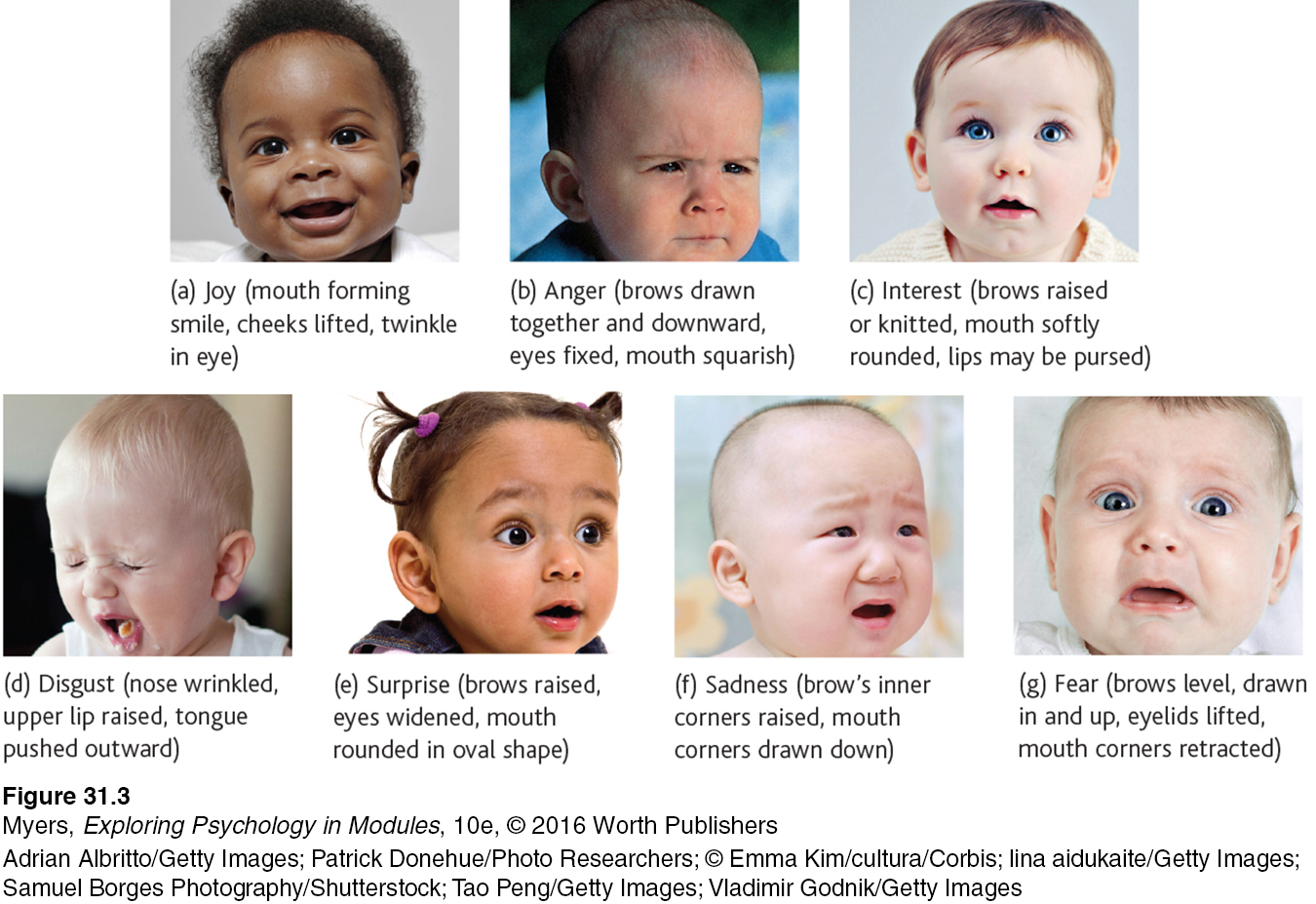

Carroll Izard (1977) isolated 10 basic emotions (joy, interest-

Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System

31-

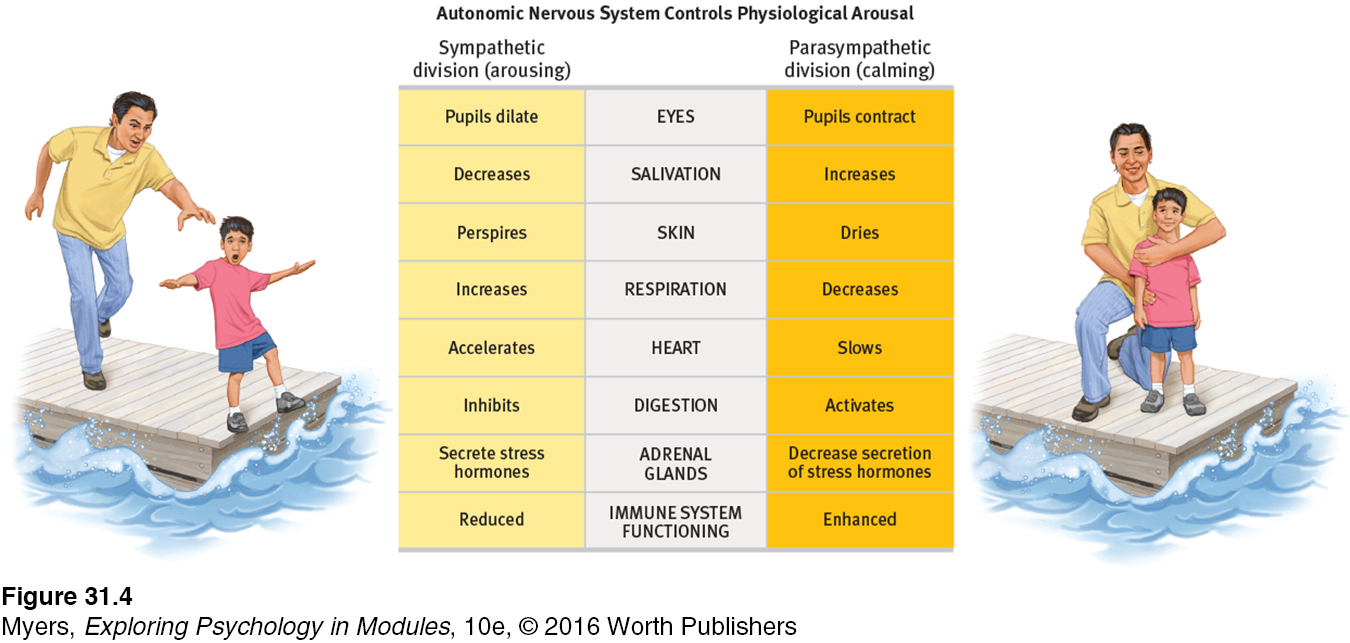

In a crisis, the sympathetic division of your autonomic nervous system (ANS) mobilizes your body for fight or flight (FIGURE 31.4). It triggers your adrenal glands to release the stress hormones epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). To provide energy, your liver pours extra sugar into your bloodstream. To help burn the sugar, your respiration increases to supply needed oxygen. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase. Your digestion slows, diverting blood from your internal organs to your muscles. With blood sugar driven into the large muscles, running becomes easier. Your pupils dilate, letting in more light. To cool your stirred-

“Fear lends wings to his feet.”

Virgil, Aeneid, 19 B.C.E.

When the crisis passes, the parasympathetic division of your ANS gradually calms your body, as stress hormones slowly leave your bloodstream. After your next crisis, think of this: Without any conscious effort, your body’s response to danger is wonderfully coordinated and adaptive—

The Physiology of Emotions

31-

Imagine conducting an experiment measuring the physiological responses of emotion. In each of four rooms, you have someone watching a movie: In the first, the person is viewing a horror show; in the second, an anger-

With training, you could probably pick out the bored viewer. But discerning physiological differences among fear, anger, and sexual arousal is much more difficult (Barrett, 2006). Different emotions can share common biological signatures.

A single brain region can also serve as the seat of seemingly different emotions. Consider the broad emotional portfolio of the insula, a neural center deep inside the brain. The insula is activated when we experience various negative social emotions, such as disgust. In brain scans, it becomes active when people bite into some disgusting food, smell disgusting food, think about biting into a disgusting cockroach, or feel moral disgust over a sleazy business exploiting a saintly widow (Sapolsky, 2010). Similar multitasking regions are found in other brains areas.

Yet our emotions—

“No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.”

C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed, 1961

Some of our emotions also differ in their brain circuits (Panksepp, 2007). Observers watching fearful faces showed more amygdala activity than did other observers who watched angry faces (Whalen et al., 2001). Brain scans and EEG recordings show that emotions also activate different areas of the brain’s cortex. When you experience negative emotions such as disgust, your right prefrontal cortex tends to be more active than the left. Depression-

Positive moods tend to trigger more left frontal lobe activity. People with positive personalities—

To sum up, we can’t easily see differences in emotions from tracking heart rate, breathing, and perspiration. But facial expressions and brain activity can vary from one emotion to another. So, do we, like Pinocchio, give off telltale signs when we lie? For more on that question, see Thinking Critically About: Lie Detection.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Lie Detection

31-

polygraph a machine, commonly used in attempts to detect lies, that measures several of the physiological responses (such as perspiration and cardiovascular and breathing changes) accompanying emotion.

Can a lie detector—a polygraph—reveal lies? Polygraphs don’t literally detect lies. Instead, they measure emotion-

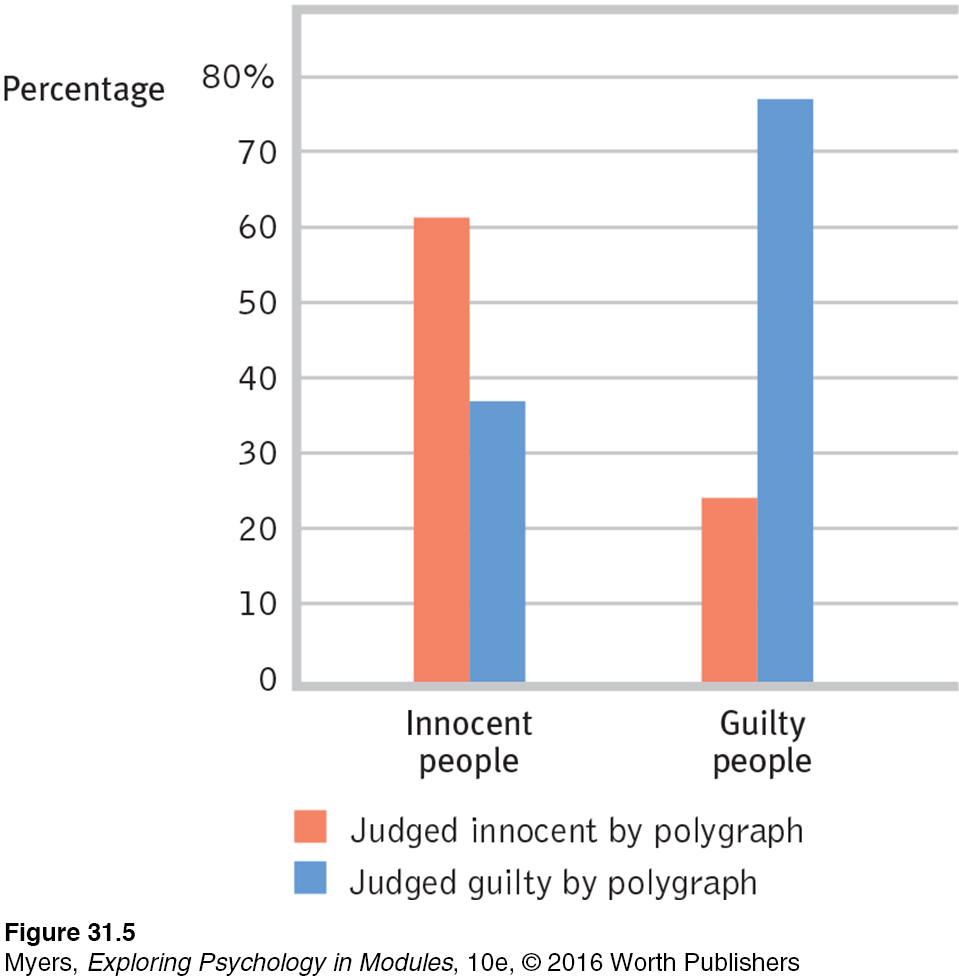

Critics point out two problems: First, our physiological arousal is much the same from one emotion to another. Anxiety, irritation, and guilt all prompt similar physiological reactivity. Second, many innocent people do respond with heightened tension to the accusations implied by the critical questions (FIGURE 31.5). Many rape victims, for example, have “failed” these tests when reacting emotionally but truthfully (Lykken, 1991).

A 2002 U.S. National Academy of Sciences report noted that “no spy has ever been caught [by] using the polygraph.” It is not for lack of trying. The FBI, CIA, and U.S. Departments of Defense and Energy have tested tens of thousands of employees, and polygraph use in Europe has also increased (Meijer & Verschuere, 2010). Yet Aldrich Ames, a Russian spy within the CIA, went undetected. Ames took many “polygraph tests and passed them all,” noted Robert Park (1999). “Nobody thought to investigate the source of his sudden wealth—

A more effective lie detection approach uses a guilty knowledge test, which assesses a suspect’s physiological responses to crime-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How do the two divisions of the autonomic nervous system affect our emotional responses?