32.1 Detecting Emotion in Others

32-1 How do we communicate nonverbally?

A silent language of emotion Hindu classic dance uses the face and body to effectively convey 10 different emotions (Hejmadi et al., 2000).

© Ruby/Alamy

To Westerners, a firm handshake conveys an outgoing, expressive personality (Chaplin et al., 2000). A gaze communicates intimacy, while darting eyes signal anxiety (Kleinke, 1986; Perkins et al., 2012). When two people are passionately in love, they typically spend time—quite a bit of time—gazing into each other’s eyes (Bolmont et al., 2014; Rubin, 1970). Would such gazes stir these feelings between strangers? To find out, researchers have asked unacquainted (and presumed heterosexual) male-female pairs to gaze intently for 2 minutes either at each other’s hands or into each other’s eyes. After separating, the eye gazers reported feeling a tingle of attraction and affection (Kellerman et al., 1989).

Most of us read nonverbal cues well. Shown 10 seconds of video from the end of a speed-dating interaction, people can often detect whether one person is attracted to the other (Place et al., 2009). We are adept at detecting a subtle smile (Maher et al., 2014). We also excel at detecting nonverbal threat. We readily sense subliminally presented negative words, such as snake or bomb (Dijksterhuis & Aarts, 2003). In a crowd, angry faces will “pop out” (Hansen & Hansen, 1988; Pinkham et al., 2010). Signs of status are also easy to spot. When shown someone with arms raised, chest expanded, and a slight smile, people—from Canadian undergraduates to Fijian villagers—perceive that person as experiencing pride and having high status (Tracy et al., 2013).

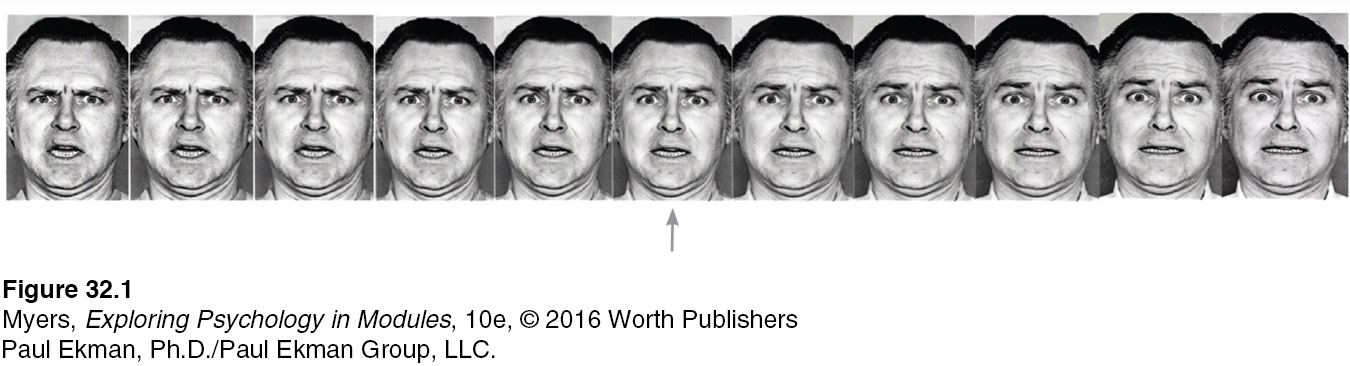

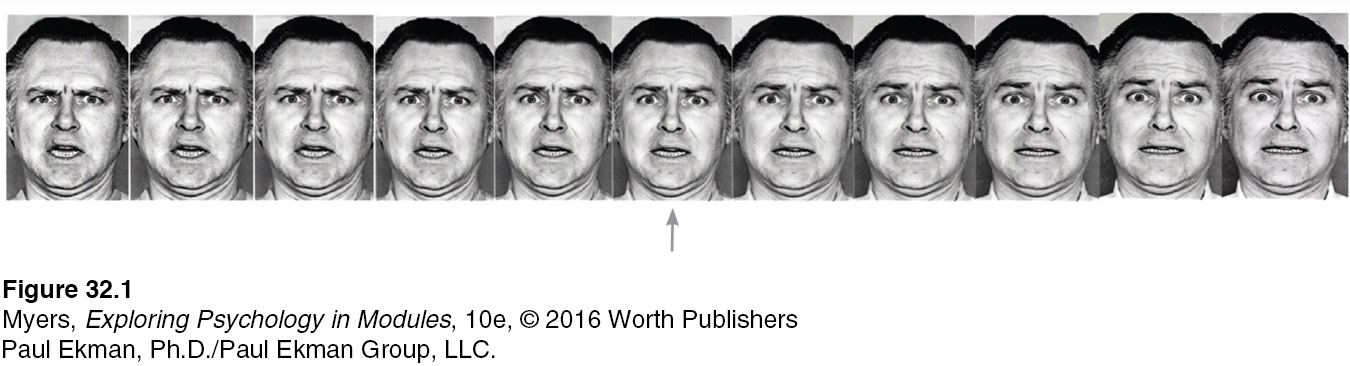

Experience can sensitize us to particular emotions, as shown by experiments using a series of faces (like those in FIGURE 32.1) that morph from anger to fear (or sadness). Viewing such faces, physically abused children are much quicker than other children to spot the signals of anger. Shown a face that is 50 percent fear and 50 percent anger, those with a history of being abused are more likely to perceive anger than fear. Their perceptions become sensitively attuned to glimmers of danger that nonabused children miss.

Figure 10.14: FIGURE 32.1 Experience influences how we perceive emotions Viewing the morphed middle face, evenly mixing anger with fear, physically abused children were more likely than nonabused children to perceive the face as angry (Pollak & Kistler, 2002; Pollak & Tolley-Schell, 2003).

Paul Ekman, Ph.D./Paul Ekman Group, LLC.

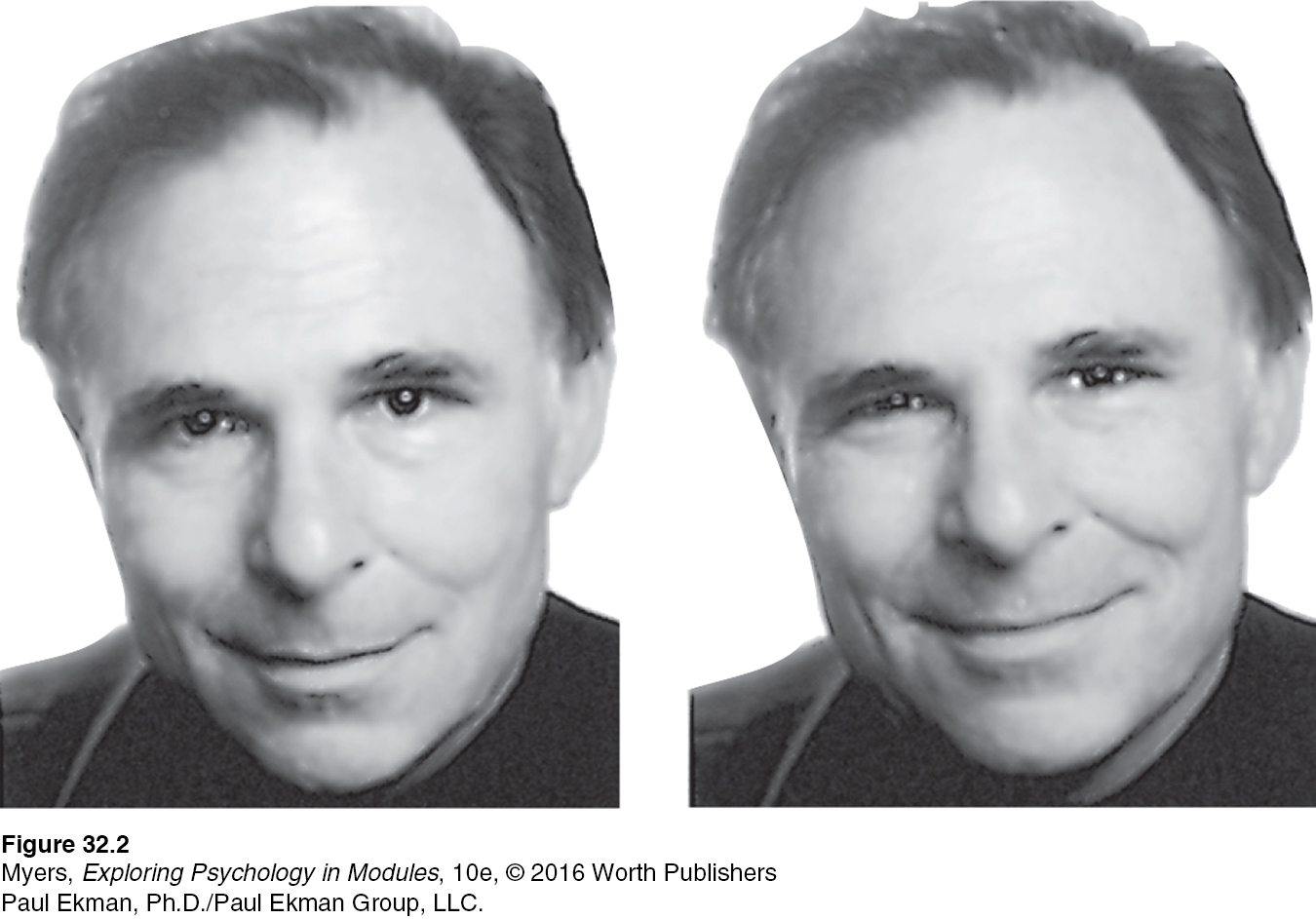

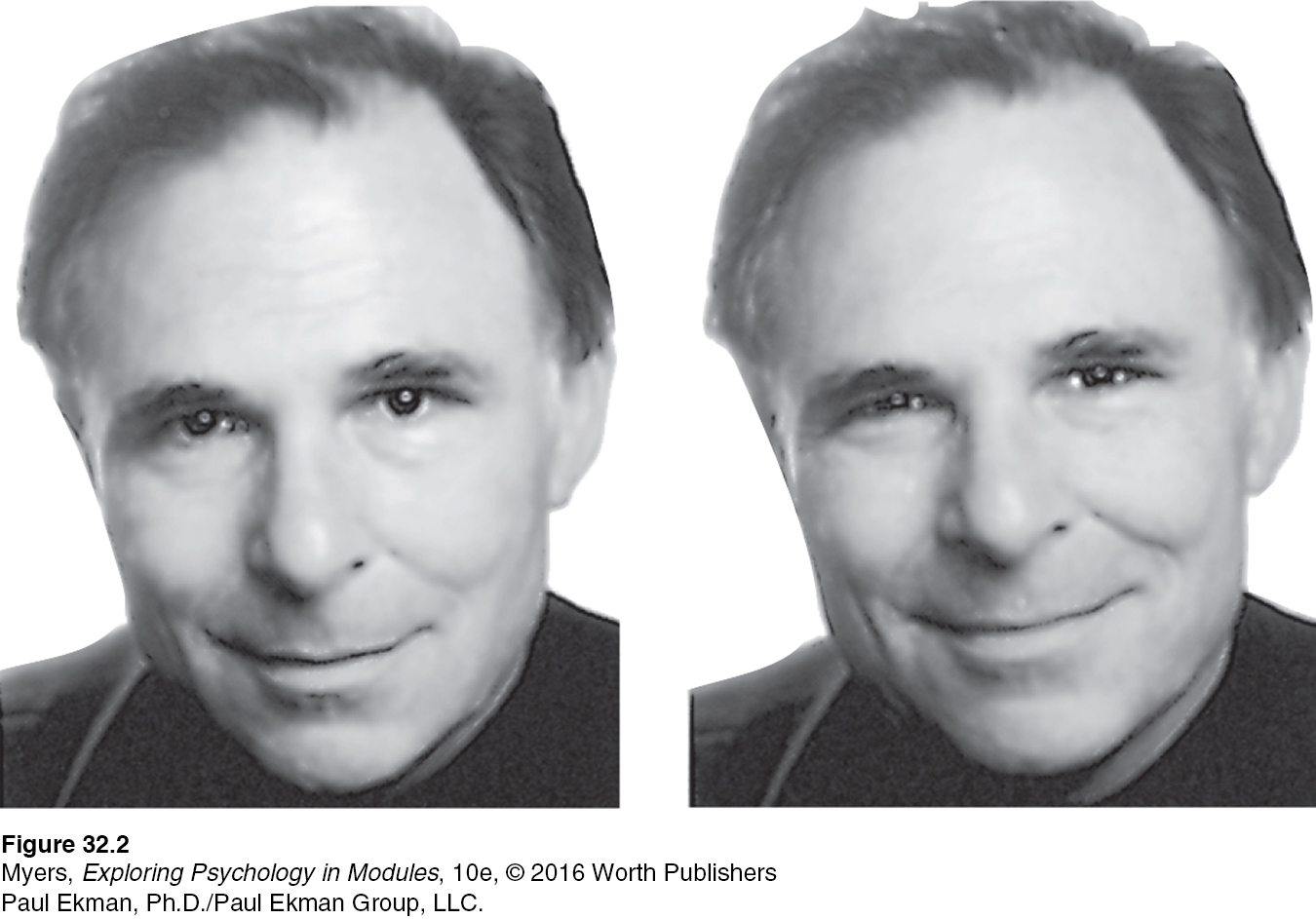

Figure 10.15: FIGURE 32.2 Which of researcher Paul Ekman’s smiles is feigned, which natural? The smile on the right engages the facial muscles of a natural smile.

Paul Ekman, Ph.D./Paul Ekman Group, LLC.

Hard-to-control facial muscles may reveal signs of emotions, even ones you are trying to conceal. Lifting just the inner part of your eyebrows, which few people do consciously, reveals distress or worry. Eyebrows raised and pulled together signal fear. Activated muscles under the eyes and raised cheeks suggest a natural smile. A feigned smile, such as one we make for a photographer, is often frozen in place for several seconds, then suddenly switched off (FIGURE 32.2). Genuine happy smiles tend to be briefer and to fade less abruptly (Bugental, 1986).

Our brain is an amazing detector of subtle expressions. When researchers filmed teachers talking to unseen schoolchildren, a mere 10-second clip of the teacher’s voice or face provided enough clues for both young and old viewers to determine whether the teacher liked and admired a child (Babad et al., 1991). In other experiments, even glimpsing a face for one-tenth of a second enabled viewers to judge people’s attractiveness or trustworthiness or to rate politicians’ competence and predict their voter support (Willis & Todorov, 2006). “First impressions … occur with astonishing speed,” note Christopher Olivola and Alexander Todorov (2010).

Despite our brain’s emotion-detecting skill, we find it difficult to detect deceiving expressions (Porter & ten Brinke, 2008). The behavioral differences between liars and truth tellers are too minute for most people to detect (Hartwig & Bond, 2011). In one digest of many studies, people were just 54 percent accurate in discerning truth from lies—barely better than a coin toss (Bond & DePaulo, 2006). Moreover, the available research indicates that virtually no one—save perhaps police professionals in high-stakes situations—beats chance by much (Bond & DePaulo, 2008; O’Sullivan et al., 2009).

Page 397

Some of us are, however, more sensitive than others to physical cues to various emotions. In one study, hundreds of people were asked to name the emotion displayed in brief film clips. The clips showed portions of a person’s emotionally expressive face or body, sometimes accompanied by a garbled voice (Rosenthal et al., 1979). For example, after a 2-second scene revealing only the face of an upset woman, the researchers would ask whether the woman was criticizing someone for being late or was talking about her divorce. Given such “thin slices,” some people were much better emotion detectors than others. Introverts tend to excel at reading others’ emotions, while extraverts are generally easier to read (Ambady et al., 1995).

Gestures, facial expressions, and voice tones, which are absent in written communication, convey important information. The difference was clear in one study. In one group, participants heard 30-second recordings of people describing their marital separations. In the other group, participants read a script of the recording. Those who heard the recording were better able to predict people’s current and future adjustment (Mason et al., 2010).

The absence of expressive emotion can make for ambiguous emotion in electronic communications. To partly remedy that, we sometimes embed cues to emotion (LOL!) in our messages. Without the vocal nuances that signal whether our statement is serious, kidding, or sarcastic, we are in danger of what developmental psychologist Jean Piaget called egocentrism, by failing to perceive how others interpret our “just kidding” message (Kruger et al., 2005).