29.1 Motivational Concepts

29-

motivation a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior.

Psychologists define motivation as a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. Our motivations arise from the interplay between nature (the bodily “push”) and nurture (the “pulls” from our thought processes and culture).

If our motivations get hijacked, our lives go awry. Those with substance use disorder, for example, may find their cravings for an addictive substance override their longings for sustenance, safety, and social support.

In their attempts to understand ordinary motivated behavior, psychologists have viewed it from four perspectives:

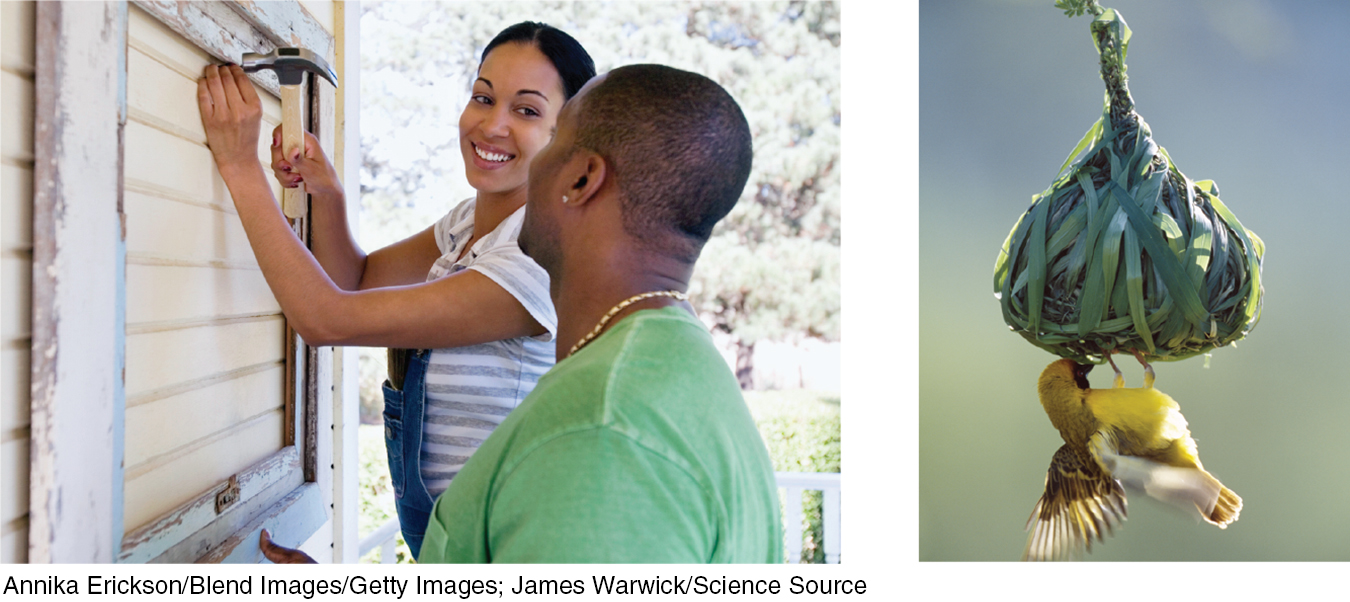

Instinct theory (now replaced by the evolutionary perspective) focuses on genetically predisposed behaviors.

Drive-

reduction theory focuses on how we respond to our inner pushes.Arousal theory focuses on finding the right level of stimulation.

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs focuses on the priority of some needs over others.

Instincts and Evolutionary Psychology

instinct a complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned.

To qualify as an instinct, a complex behavior must have a fixed pattern throughout a species and be unlearned (Tinbergen, 1951). Such behaviors are common in other species and include imprinting in birds and the return of salmon to their birthplace. A few human behaviors, such as infants’ innate reflexes to root for a nipple and suck, exhibit unlearned fixed patterns, but many more are directed by both physiological needs and psychological wants.

Although instincts cannot explain most human motives, the underlying assumption continues in evolutionary psychology: Genes do predispose some species-

Drives and Incentives

drive-reduction theory the idea that a physiological need creates an aroused tension state (a drive) that motivates an organism to satisfy the need.

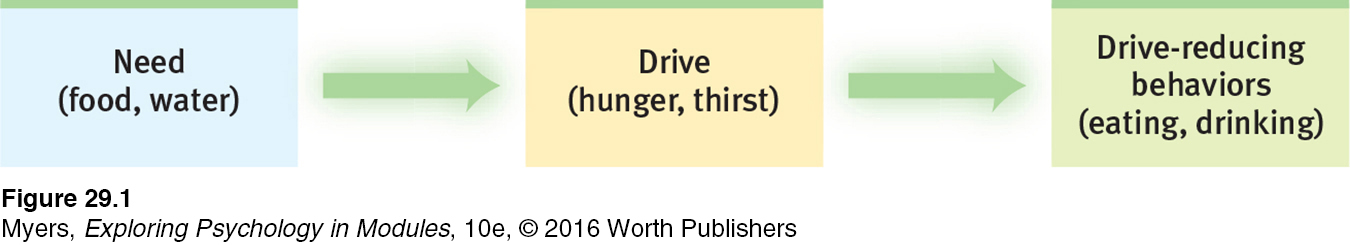

In addition to our predispositions, we have drives. Physiological needs (such as for food or water) create an aroused, motivated state—

homeostasis a tendency to maintain a balanced or constant internal state; the regulation of any aspect of body chemistry, such as blood glucose, around a particular level.

Drive reduction is one way our bodies strive for homeostasis (literally “staying the same”)—the maintenance of a steady internal state. For example, our body regulates its temperature in a way similar to a room’s thermostat. Both systems operate through feedback loops: Sensors feed room temperature to a control device. If the room’s temperature cools, the control device switches on the furnace. Likewise, if our body’s temperature cools, our blood vessels constrict (to conserve warmth) and we feel driven to put on more clothes or seek a warmer environment (FIGURE 29.1).

incentive a positive or negative environmental stimulus that motivates behavior.

Not only are we pushed by our need to reduce drives, we also are pulled by incentives—positive or negative environmental stimuli that lure or repel us. This is one way our individual learning histories influence our motives. Depending on our learning, the aroma of good food, whether fresh roasted peanuts or toasted ants, can motivate our behavior. So can the sight of those we find attractive or threatening.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. The food-

Optimum Arousal

We are much more than homeostatic systems, however. Some motivated behaviors actually increase rather than decrease arousal. Well-

So, human motivation aims not to eliminate arousal but to seek optimum levels of arousal. Having all our biological needs satisfied, we feel driven to experience stimulation and we hunger for information. Lacking stimulation, we feel bored and look for a way to increase arousal to some optimum level. If left alone by themselves, most people prefer to do something—

Yerkes-Dodson law the principle that performance increases with arousal only up to a point, beyond which performance decreases.

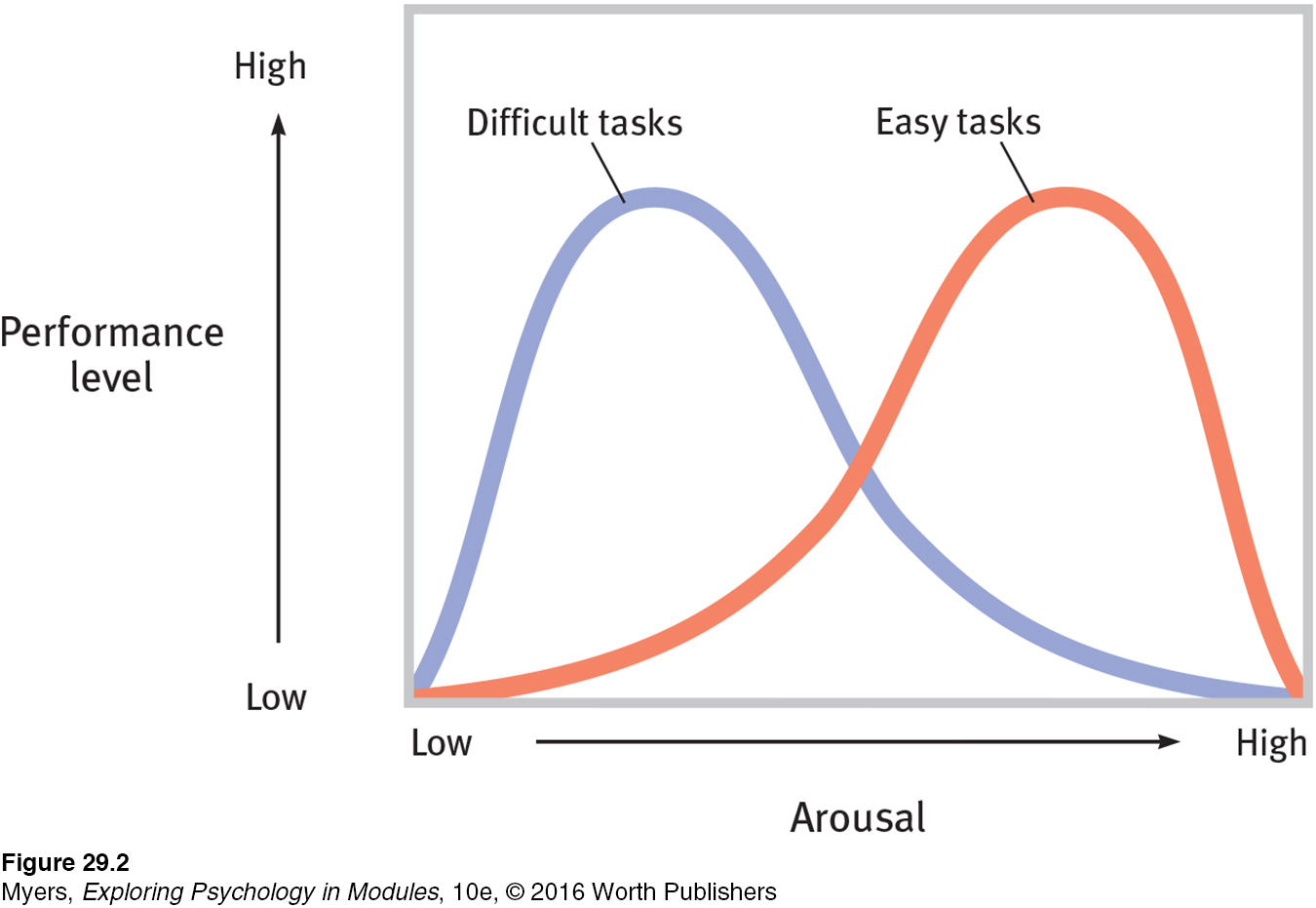

Two early twentieth-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-

learned tasks. (1) How might this phenomenon affect runners? (2) How might this phenomenon affect anxious test- takers facing a difficult exam? (3) How might the performance of anxious students be affected by relaxation training? ANSWER: (1) Runners, who are executing a well-learned task, tend to excel when aroused by competition. (2) High anxiety in test- takers, who are completing a difficult task, may disrupt their performance. (3) Teaching anxious students how to relax before an exam can enable them to perform better (Hembree, 1988).

A Hierarchy of Motives

“Hunger is the most urgent form of poverty.”

Alliance to End Hunger, 2002

Some needs take priority over others. At this moment, with your needs for air and water hopefully satisfied, other motives—

To test your understanding of the hierarchy of needs, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Building Maslow’s Hierarchy.

To test your understanding of the hierarchy of needs, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Building Maslow’s Hierarchy.

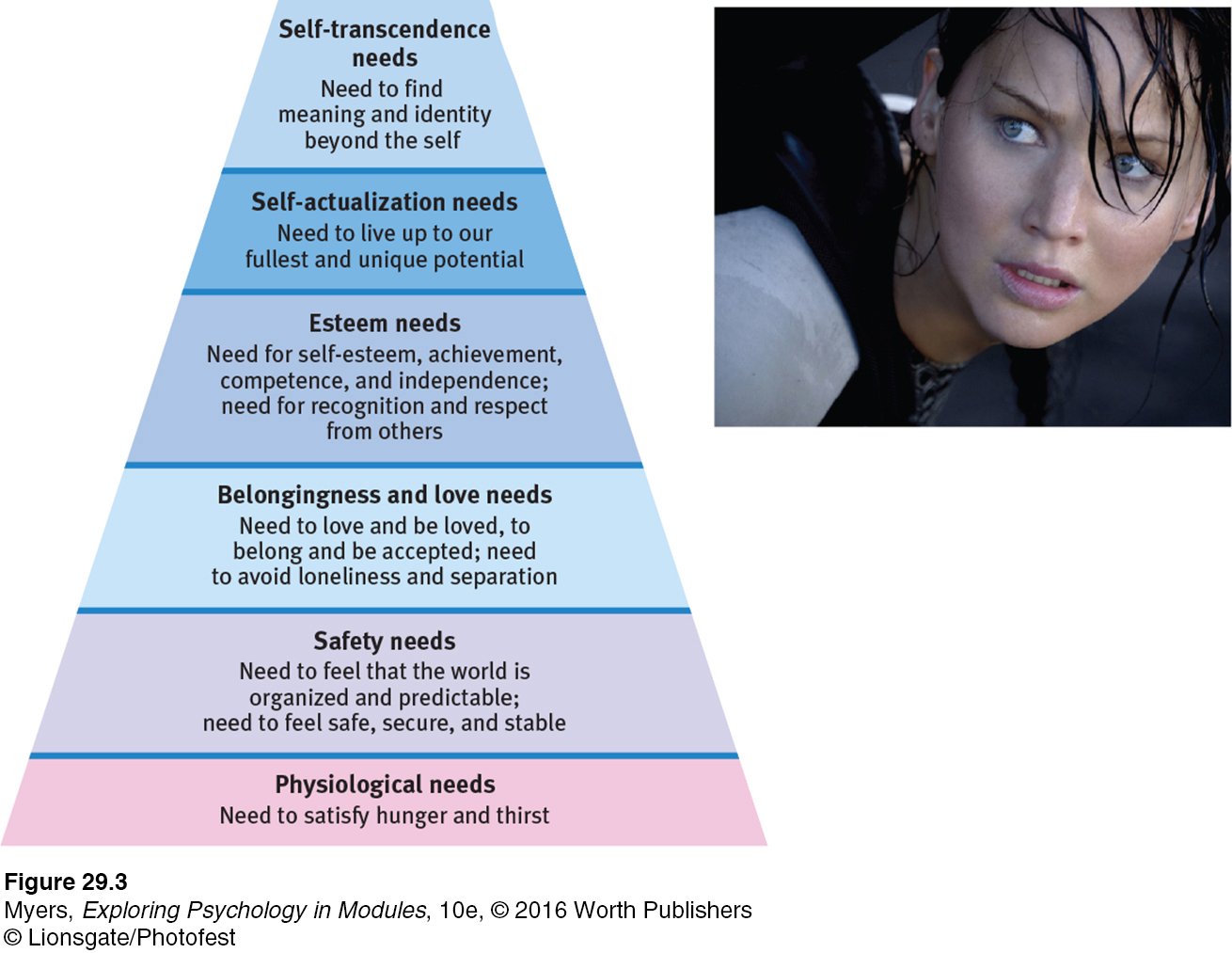

hierarchy of needs Maslow’s pyramid of human needs, beginning at the base with physiological needs that must first be satisfied before higher-

Abraham Maslow (1970) described these priorities as a hierarchy of needs (FIGURE 29.3). At the base of this pyramid are our physiological needs, such as those for food and water. Only if these needs are met are we prompted to meet our need for safety, and then to satisfy our human needs to give and receive love and to enjoy self-

Near the end of his life, Maslow proposed that some of us also reach a level of self-

The order of Maslow’s hierarchy is not universally fixed: People have starved themselves to make a political statement. Culture also influences our priorities: Self-

Nevertheless, the simple idea that some motives are more compelling than others provides a framework for thinking about motivation. Worldwide life-

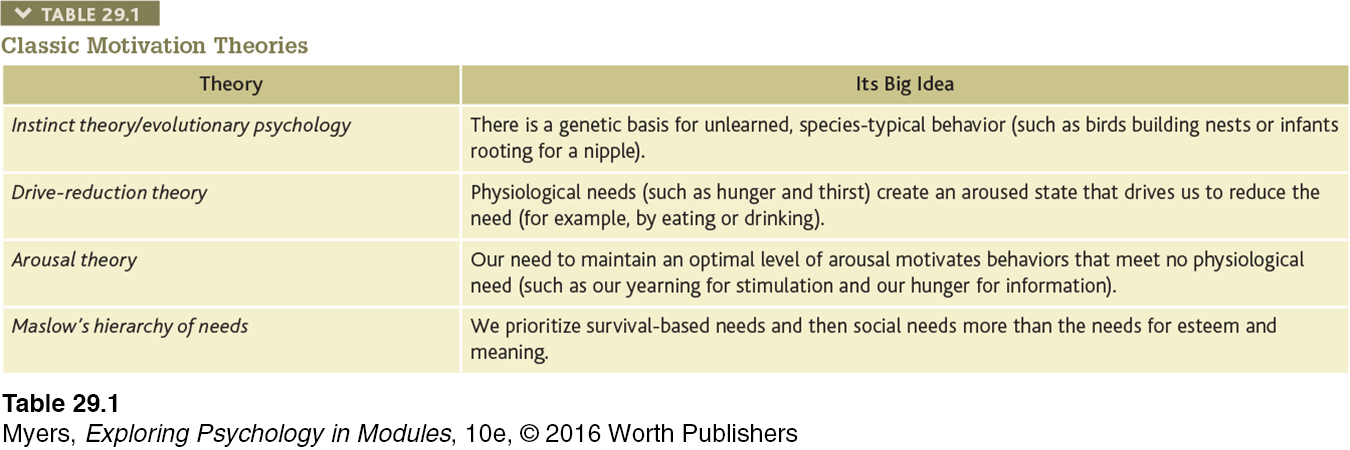

With these classic motivation theories in mind (see TABLE 10.1), let’s now take a closer look at two specific, higher-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

After hours of driving alone in an unfamiliar city, you finally see a diner. Although it looks deserted and a little creepy, you stop because you are really hungry and thirsty. How would Maslow's hierarchy of needs explain your behavior?