30.2 The Psychology of Hunger

30-

Our internal hunger games are pushed by our body chemistry and brain activity. Yet there is more to hunger than meets the stomach. This was strikingly apparent when trickster researchers tested two patients who had no memory for events occurring more than a minute ago (Rozin et al., 1998). If offered a second lunch 20 minutes after eating a normal lunch, both patients readily consumed it … and usually a third meal offered 20 minutes after they finished the second. This suggests that one part of our decision to eat is our memory of the time of our last meal. As time passes, we think about eating again, and those thoughts trigger feelings of hunger.

Taste Preferences: Biology and Culture

Body cues and environmental factors together influence not only the when of hunger, but also the what—our taste preferences. When feeling tense or depressed, do you tend to take solace in high-

Our preferences for sweet and salty tastes are genetic and universal, but conditioning can intensify or alter those preferences. People given highly salted foods may develop a liking for excess salt (Beauchamp, 1987). People sickened by a food may develop an aversion to it. (The frequency of children’s illnesses provides many chances for them to learn to avoid certain foods.)

Our culture teaches us that some foods are acceptable but others are not. Many Japanese people enjoy nattó, a fermented soybean dish that “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire,” reports smell expert Rachel Herz (2012). Although many Westerners find this disgusting, Asians, she adds, are often repulsed by what Westerners love—

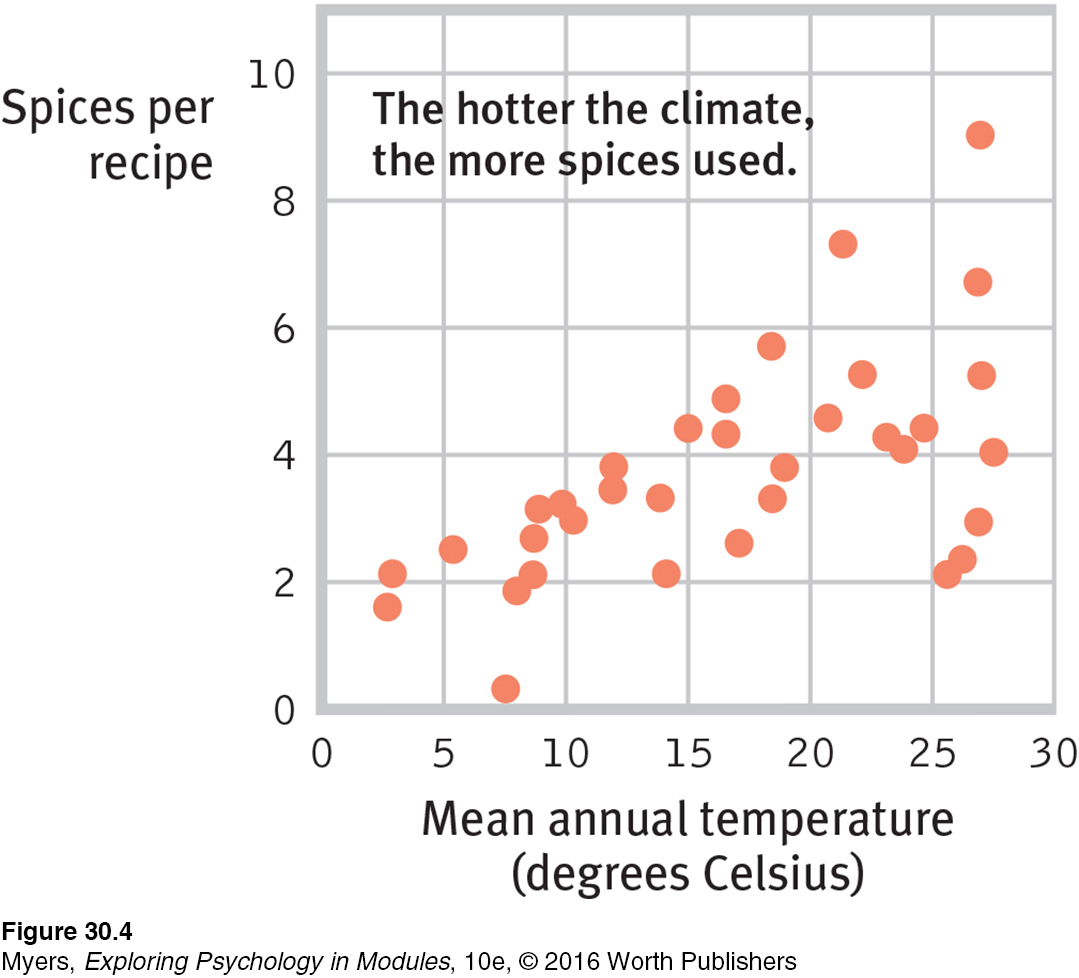

But there is biological wisdom to many of our taste preferences. For example, in hot climates (where foods spoil more quickly) recipes often include spices that inhibit bacteria growth (FIGURE 30.4). Pregnancy-

Rats tend to avoid unfamiliar foods (Sclafani, 1995). So do we, especially those that are animal-

Situational Influences on Eating

To a surprising extent, situations also control our eating—

Arousing appetite In one experiment, watching an intense action movie (rather than a nonarousing interview) doubled snacking (Tal et al., 2014).

Friends and food Do you eat more when eating with others? Most of us do (Herman et al., 2003; Hetherington et al., 2006). After a party, you may realize you’ve overeaten. This happens because the presence of others tends to amplify our natural behavior tendencies. (We explore this social facilitation in the Social Psychology modules.)

Serving size is significant “Unit bias” occurs with similar mindlessness. Investigators studied the effects of portion size by offering people varieties of free snacks. In an apartment lobby, they laid out full or half pretzels, big or little Tootsie Rolls, or a small or large serving scoop with a bowl of M&M’s. Their consistent result: Offered a supersized portion, people put away more calories. In another study, people ate more pasta when given a bigger plate (Van Ittersum & Wansink, 2012). Children also eat more when using adult-

sized (rather than child- sized) dishware (DiSantis et al., 2013). Even nutrition experts helped themselves to 31 percent more ice cream when given a big bowl rather than a small one (Wansink, 2006, 2014). Portion size matters. Page 382Selections stimulate Food variety also stimulates eating. Offered a dessert buffet, we eat more than we do when choosing a portion from one favorite dessert. For our early ancestors, variety was healthy. When foods were abundant and varied, eating more provided a wide range of vitamins and minerals and produced protective fat for winter cold or famine. When a bounty of varied foods was unavailable, eating less extended the food supply until winter or famine ended (Polivy et al., 2008; Remick et al., 2009).

Nudging nutrition One research team quadrupled carrots taken by offering schoolchildren carrots before they picked up other foods in a lunch line (Redden et al., 2015). A planned new school lunch tray will put fruits and veggies up front, and spread the entrée out in a shallow compartment to make it look bigger (Wansink, 2014).

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Using Larger Dinner Plates Makes People Gain Weight?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Using Larger Dinner Plates Makes People Gain Weight?

RETRIEVE IT

Question

After an eight-