33.1 Stress: Some Basic Concepts

33-

stress the process by which we perceive and respond to certain events, called stressors, that we appraise as threatening or challenging.

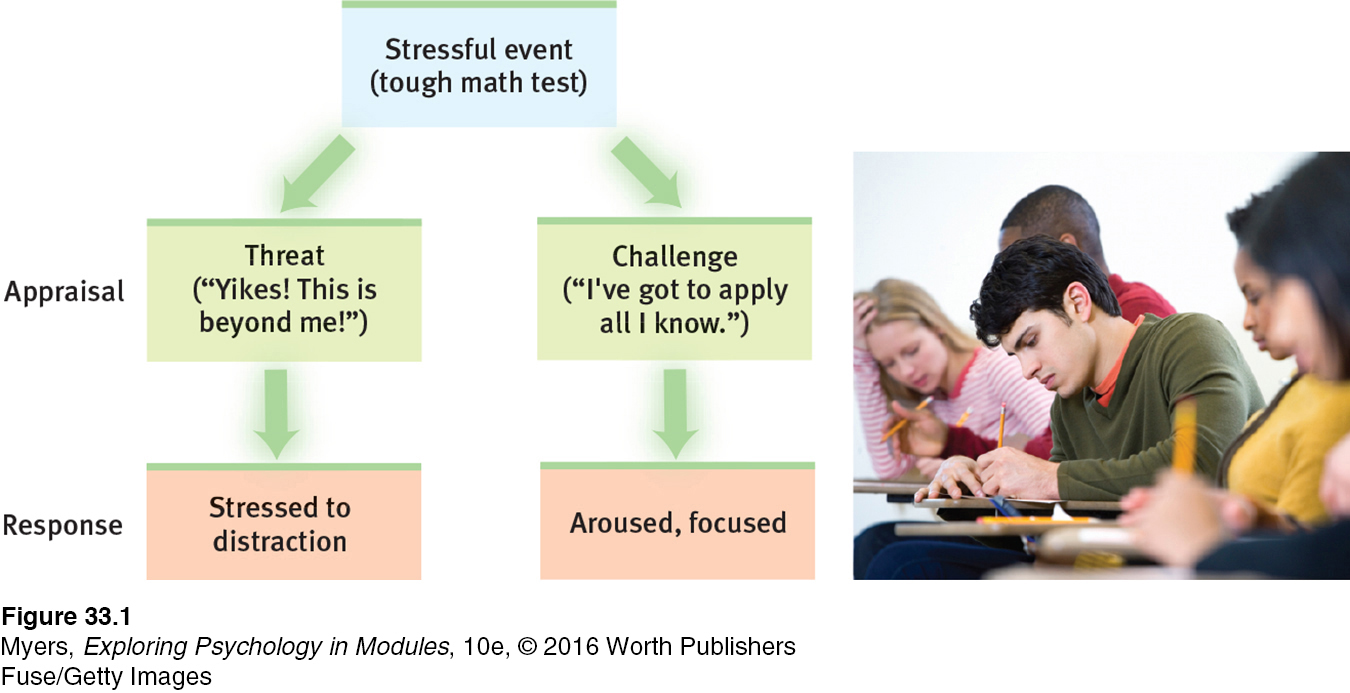

Psychologists define stress as the process of appraising and responding to a threatening or challenging event (FIGURE 33.1). But stress is a slippery concept. We sometimes use the word informally to describe threats or challenges (“Ben was under a lot of stress”), and at other times our responses (“Ben experienced acute stress”). To a psychologist, the dangerous truck ride was a stressor. Ben’s physical and emotional responses were a stress reaction. And the process by which he related to the threat was stress.

Stress arises less from events themselves than from how we appraise them (Lazarus, 1998). One person, alone in a house, ignores its creaking sounds and experiences no stress; someone else suspects an intruder and becomes alarmed. One person regards a new job as a welcome challenge; someone else appraises it as risking failure. When short-

“Too many parents make life hard for their children by trying, too zealously, to make it easy for them.”

German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–

But extreme or prolonged stress can harm us. Demanding jobs that mentally exhaust workers also can damage their physical health (Huang et al., 2010). Pregnant women with overactive stress systems tend to have shorter pregnancies, which pose health risks for their infants (Entringer et al., 2011).

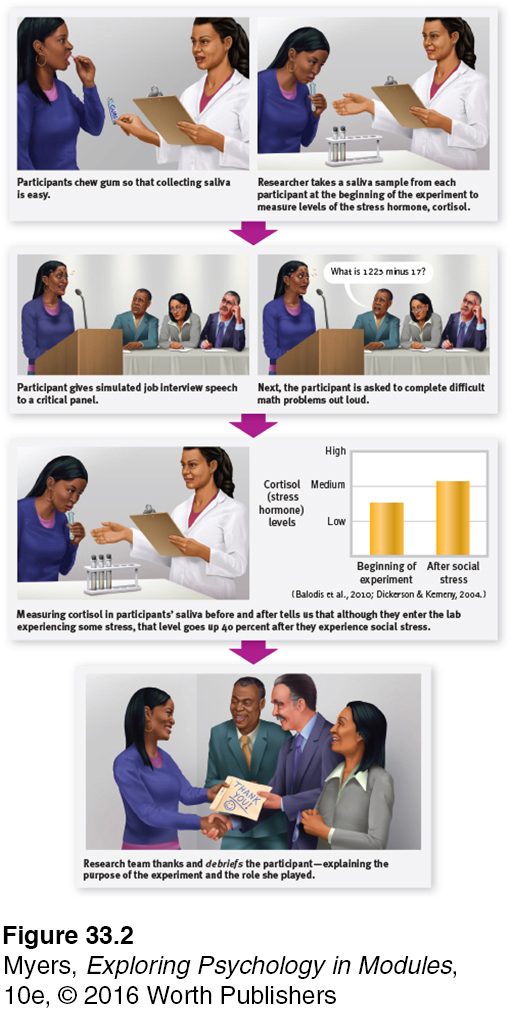

So there is an interplay between our head and our health. Psychological states are physiological events that influence other parts of our physiological system. Just pausing to think about biting into an orange wedge—

Stressors—Things That Push Our Buttons

Stressors fall into three main types: catastrophes, significant life changes, and daily hassles. All can be toxic.

CATASTROPHES Catastrophes are unpredictable large-

For those who respond to catastrophes by relocating to another country, the stress may be twofold. The trauma of uprooting and family separation may combine with the challenges of adjusting to a new culture’s language, ethnicity, climate, and social norms (Pipher, 2002; Williams & Berry, 1991). In the first half-

SIGNIFICANT LIFE CHANGES Life transitions—

Some psychologists study the health effects of life changes by following people over time. Others compare the life changes recalled by those who have or have not suffered a specific health problem, such as a heart attack. In such studies, those recently widowed, fired, or divorced have been more vulnerable to disease (Dohrenwend et al., 1982; Strully, 2009). One Finnish study of 96,000 widowed people found that the survivor’s risk of death doubled in the week following a partner’s death (Kaprio et al., 1987). A cluster of crises—

DAILY HASSLES AND SOCIAL STRESS Events don’t have to remake our lives to cause stress. Stress also comes from daily hassles—

Many people face more significant daily hassles. As the Great Recession of 2008–

Daily economic pressures may be compounded by prejudice against our gender identity, sexual orientation, or race, which—

The Stress Response System

Medical interest in stress dates back to Hippocrates (460–

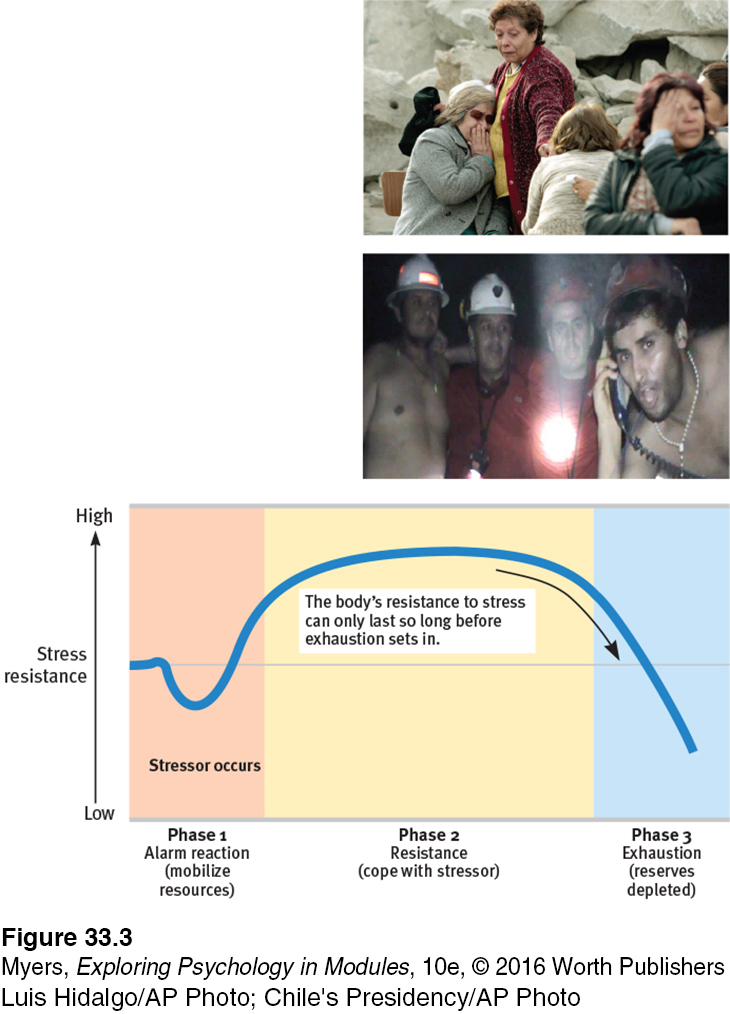

general adaptation syndrome (GAS) Selye’s concept of the body’s adaptive response to stress in three phases—

Canadian scientist Hans Selye’s (1936, 1976) 40 years of research on stress extended Cannon’s findings. His studies of animals’ reactions to various stressors, such as electric shock and surgery, helped make stress a major concept in both psychology and medicine. Selye proposed that the body’s adaptive response to stress is so general that, like a single burglar alarm, it sounds, no matter what intrudes. He named this response the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), and he saw it as a three-

In Phase 1, you have an alarm reaction, as your sympathetic nervous system is suddenly activated. Your heart rate zooms. Blood is diverted to your skeletal muscles. You feel the faintness of shock. With your resources mobilized, you are now ready to fight back.

During Phase 2, resistance, your temperature, blood pressure, and respiration remain high. Your adrenal glands pump hormones into your bloodstream. You are fully engaged, summoning all your resources to meet the challenge. As time passes, with no relief from stress, your body’s reserves dwindle.

You have reached Phase 3, exhaustion. With exhaustion, you become more vulnerable to illness or even, in extreme cases, collapse and death.

Selye’s basic point: Although the human body copes well with temporary stress, prolonged stress can damage it. Severe childhood stress, such as from abuse, gets under the skin, leading to greater stress responses and disease risk (Hanson et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2011). Even fearful, stressed rats have been found to die sooner, after about 600 days, than their more confident siblings, which average 700-

tend and befriend under stress, people (especially women) often provide support to others (tend) and bond with and seek support from others (befriend).

There are other ways to deal with stress. One option is a common response to a loved one’s death: Withdraw. Pull back. Conserve energy. Faced with an extreme disaster, such as a ship sinking, some people become paralyzed by fear. Another option (often found among women) is to give and seek support—

Facing stress, men more often than women tend to withdraw socially, turn to alcohol, or become aggressive. Women more often respond to stress by nurturing and banding together. This may in part be due to oxytocin, a stress-

It often pays to spend our resources in fighting or fleeing an external threat. But we do so at a cost. When stress is momentary, the cost is small. When stress persists, the cost may be much higher, in the form of lowered resistance to infections and other threats to mental and physical well-

“You’ve got to know when to hold ’em; know when to fold ’em. Know when to walk away, and know when to run.”

Kenny Rogers, “The Gambler,” 1978

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The stress response system: When alerted to a negative, uncontrollable event, our nervous system arouses us. Heart rate and respiration (increase/decrease). Blood is diverted from digestion to the skeletal . The body releases sugar and fat. All this prepares the body for the response.