33.2 Stress and Vulnerability to Disease

33-

health psychology a subfield of psychology that provides psychology’s contribution to behavioral medicine.

psychoneuroimmunology the study of how psychological, neural, and endocrine processes together affect the immune system and resulting health.

To study how stress and healthy and unhealthy behaviors influence health and illness, psychologists and physicians have created the interdisciplinary field of behavioral medicine, integrating behavioral and medical knowledge. One subfield, health psychology, provides psychology’s contribution to behavioral medicine. A branch of health psychology called psychoneuroimmunology focuses on mind-

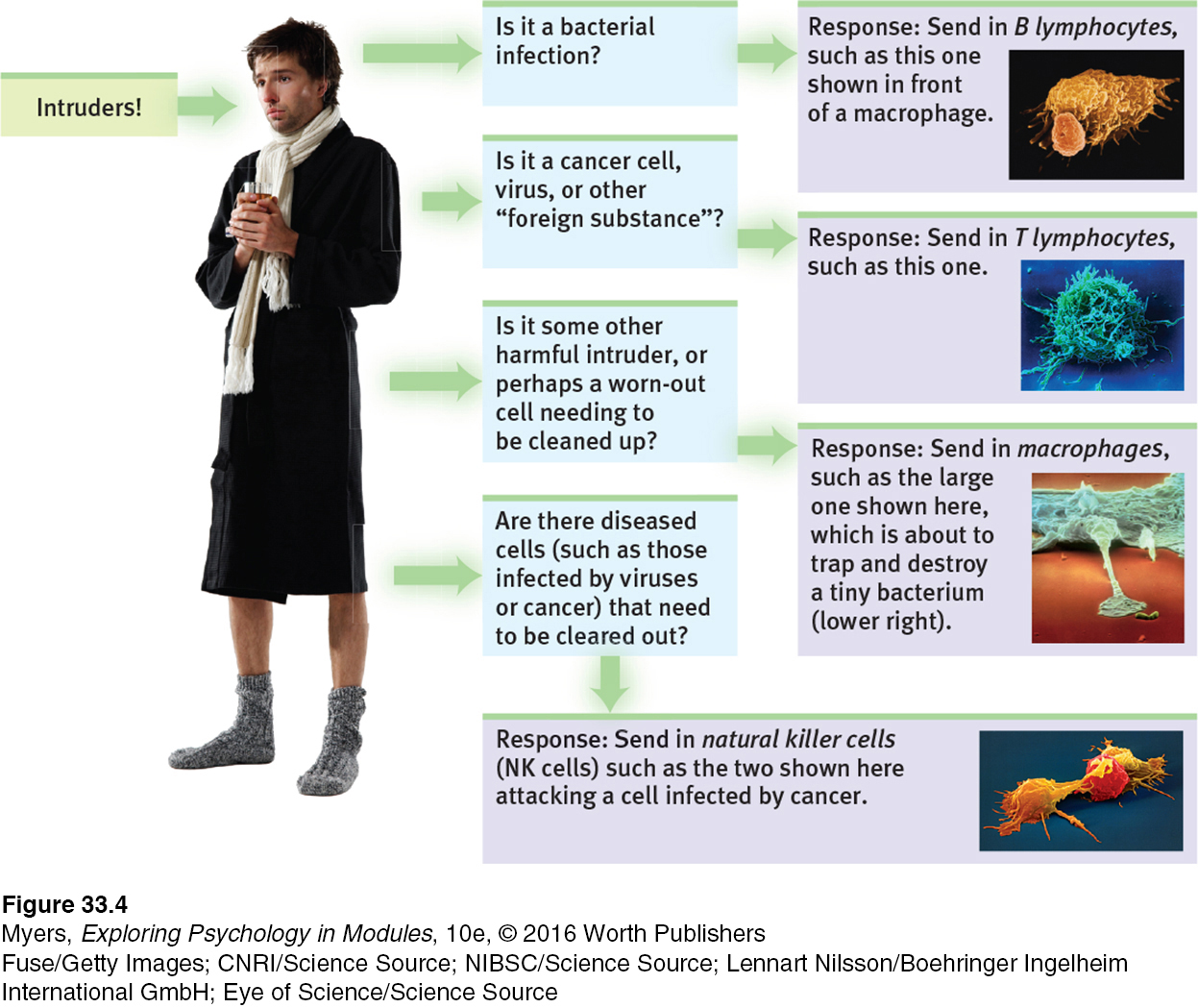

If you’ve ever had a stress headache, or felt your blood pressure rise with anger, you don’t need to be convinced that our psychological states have physiological effects. Stress can even leave you less able to fight off disease because your nervous and endocrine systems influence your immune system (Sternberg, 2009). You can think of your immune system as a complex surveillance system. When it functions properly, it keeps you healthy by isolating and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other invaders. Four types of cells are active in these search-

B lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the bone marrow and release antibodies that fight bacterial infections.

T lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the thymus and other lymphatic tissue and attack cancer cells, viruses, and foreign substances.

Macrophages (“big eaters”) identify, pursue, and ingest harmful invaders and worn-

out cells. Natural killer cells (NK cells) pursue diseased cells (such as those infected by viruses or cancer).

Your age, nutrition, genetics, body temperature, and stress all influence your immune system’s activity. If it doesn’t function properly, your immune system can err in two directions:

Responding too strongly, the immune system may attack the body’s own tissues, causing an allergic reaction or a self-

attacking disease such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, or some forms of arthritis. Women, who are immunologically stronger than men, are more susceptible to self- attacking diseases (Nussinovitch & Schoenfeld, 2012; Schwartzman- Morris & Putterman, 2012). Underreacting, the immune system may allow a bacterial infection to flare, a dormant virus to erupt, or cancer cells to multiply. To protect transplanted organs, which the recipient’s immune system would view as a foreign body, surgeons may deliberately suppress the patient’s immune system.

Stress can also trigger immune suppression by reducing the release of disease-

Human immune systems react similarly. Some examples:

Surgical wounds heal more slowly in stressed people. In one experiment, dental students received punch wounds (precise small holes punched in the skin). Compared with wounds placed during summer vacation, those placed three days before a major exam healed 40 percent more slowly (Kiecolt-

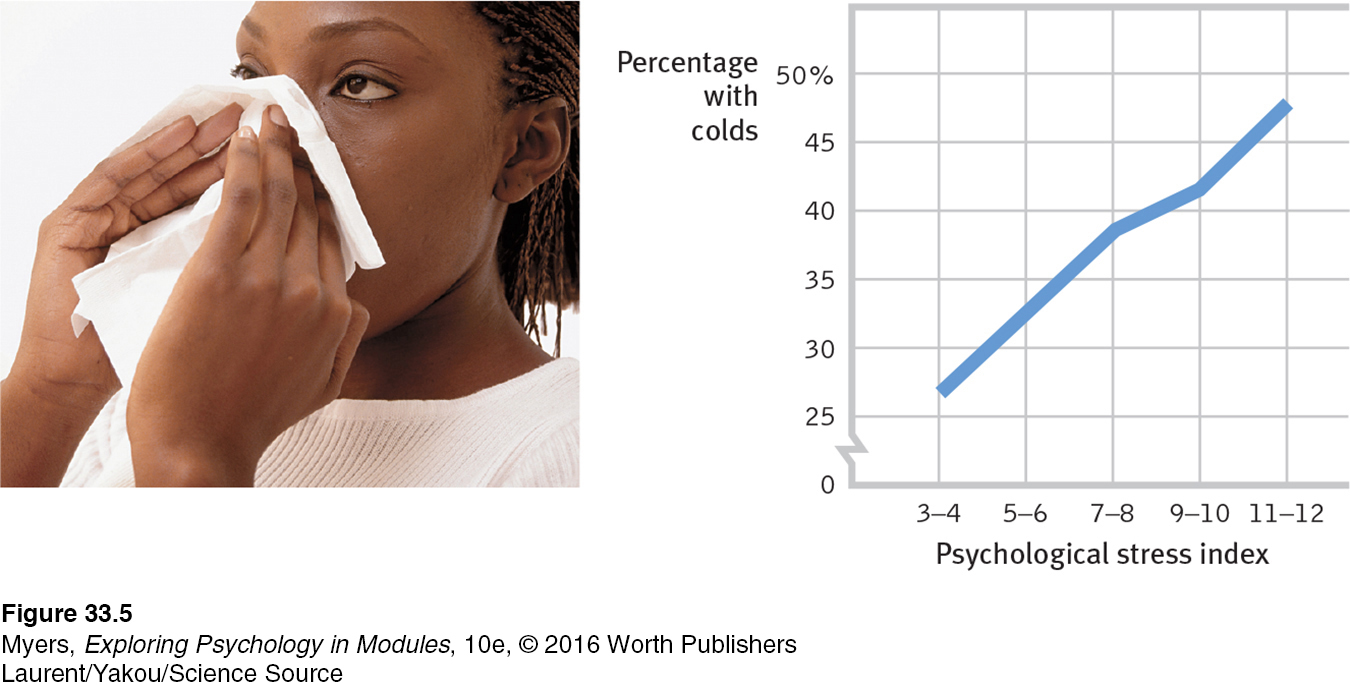

Glaser et al., 1998). In other studies, marriage conflict has also slowed punch- wound healing (Kiecolt- Glaser et al., 2005). Page 412Stressed people are more vulnerable to colds. Major life stress increases the risk of a respiratory infection (Pedersen et al., 2010). When researchers dropped a cold virus into the noses of stressed and relatively unstressed people, 47 percent of those living stress-

filled lives developed colds (FIGURE 33.5). Among those living relatively free of stress, only 27 percent did. In follow- up research, the happiest and most relaxed people were likewise markedly less vulnerable to an experimentally delivered cold virus (Cohen et al., 2003, 2006; Cohen & Pressman, 2006). Vaccine effectiveness declines with stress. Nurses gave older adults a flu vaccine and then measured how well their bodies fought off bacteria and viruses. The vaccine was most effective among those who reported experiencing low stress (Segerstrom et al., 2012).

The stress effect on immunity makes physiological sense. It takes energy to track down invaders, produce swelling, and maintain fevers. Thus, when diseased, your body reduces its muscular energy output by decreasing activity and increasing sleep. Stress does the opposite. It creates a competing energy need. During an aroused fight-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The field of studies mind-body interactions, including the effects of psychological, neural, and endocrine functioning on the immune system and overall health.

Question

What general effect does stress have on our overall health?

Stress and AIDS

We know that stress suppresses immune system functioning. What does this mean for people with AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome)? As its name tells us, AIDS is an immune disorder, caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although AIDS-

Stress cannot give people AIDS. But could stress and negative emotions speed the transition from HIV infection to AIDS? And might stress predict a faster decline in those with AIDS? An analysis of 33,252 participants from around the world suggests the answer to both questions is Yes (Chida & Vedhata, 2009). The greater the stress that HIV-

Would efforts to reduce stress help control the disease? Again, the answer appears to be Yes. Educational initiatives, bereavement support groups, cognitive therapy, relaxation training, and exercise programs that reduce distress have all had positive consequences for HIV-

Stress and Cancer

Stress does not create cancer cells. But in a healthy, functioning immune system, lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells search out and destroy cancer cells and cancer-

“I didn’t give myself cancer.”

Mayor Barbara Boggs Sigmund (1939–

Does this stress-

For a 7-

For a 7-

When organic causes of illness are unknown, it is tempting to invent psychological explanations. Before the germ that causes tuberculosis was discovered, personality explanations of TB were popular (Sontag, 1978).

One danger in hyping reports on emotions and cancer is that some patients may then blame themselves for their illness: “If only I had been more expressive, relaxed, and hopeful.” A corollary danger is a “wellness macho” among the healthy, who take credit for their “healthy character” and lay a guilt trip on the ill: “She has cancer? That’s what you get for holding your feelings in and being so nice.” Dying thus becomes the ultimate failure.

It’s important enough to repeat: Stress does not create cancer cells. At worst, it may affect their growth by weakening the body’s natural defenses against multiplying malignant cells (Lutgendorf et al., 2008; Nausheen et al., 2010; Sood et al., 2010). Although a relaxed, hopeful state may enhance these defenses, we should be aware of the thin line that divides science from wishful thinking. The powerful biological processes at work in advanced cancer or AIDS are not likely to be completely derailed by avoiding stress or maintaining a relaxed but determined spirit (Anderson, 2002; Kessler et al., 1991). And that explains why research consistently indicates that psychotherapy does not extend cancer patients’ survival (Coyne et al., 2007, 2009; Coyne & Tennen, 2010).

Stress and Heart Disease

33-

Depart from reality for a moment. In this new world, you wake up each day, eat your breakfast, and check the news. Four 747 jumbo jet airplanes crashed yesterday and all 1642 passengers died. You finish your breakfast, grab your things, and head to class. It’s just an average day.

coronary heart disease the clogging of the vessels that nourish the heart muscle; the leading cause of death in many developed countries.

Replace airline crashes with coronary heart disease, the United States’ leading cause of death, and you have reentered reality. About 610,000 Americans die annually from heart disease (CDC, 2015). High blood pressure and a family history of the disease increase the risk. So do smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, and a high cholesterol level.

Stress and personality also play a big role in heart disease. The more psychological trauma people experience, the more their bodies generate inflammation, which is associated with heart and other health problems (O’Donovan et al., 2012). Plucking a hair and measuring its level of cortisol (a stress hormone) can help predict whether a child has experienced prolonged stress or an adult will have a future heart attack (Karlén et al., 2015; Pereg et al., 2011).

TYPE A PERSONALITY In a classic study, Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues tested the idea that stress increases heart disease risk by measuring the blood cholesterol level and clotting speed of 40 U.S. male tax accountants at different times of year (Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). From January through March, the test results were completely normal. Then, as the accountants began scrambling to finish their clients’ tax returns before the April 15 filing deadline, their cholesterol and clotting measures rose to dangerous levels. In May and June, with the deadline past, the measures returned to normal. For these men, stress predicted heart attack risk. Blood pressure also rises as students approach stressful exams (Conley & Lehman, 2012).

Type A Friedman and Rosenman’s term for competitive, hard-

Type B Friedman and Rosenman’s term for easygoing, relaxed people.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

So, are some of us at high risk of stress-

Nine years later, 257 men had suffered heart attacks, and 69 percent of them were Type A. Moreover, not one of the “pure” Type Bs—

In both India and America, Type A bus drivers are literally hard-

As often happens in science, this exciting discovery provoked enormous public interest. After that initial honeymoon period, researchers wanted to know more. Was the finding reliable? If so, what was the toxic component of the Type A profile: Time-

More than 700 studies have now explored possible psychological correlates or predictors of cardiovascular health (Chida & Hamer, 2008; Chida & Steptoe, 2009). These reveal that Type A’s toxic core is negative emotions—

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.”

Chinese proverb

Hundreds of other studies of young and middle-

TYPE D PERSONALITY In recent years, another personality type has interested stress and heart disease researchers. Type A individuals direct their negative emotion toward dominating others. People with another personality type—

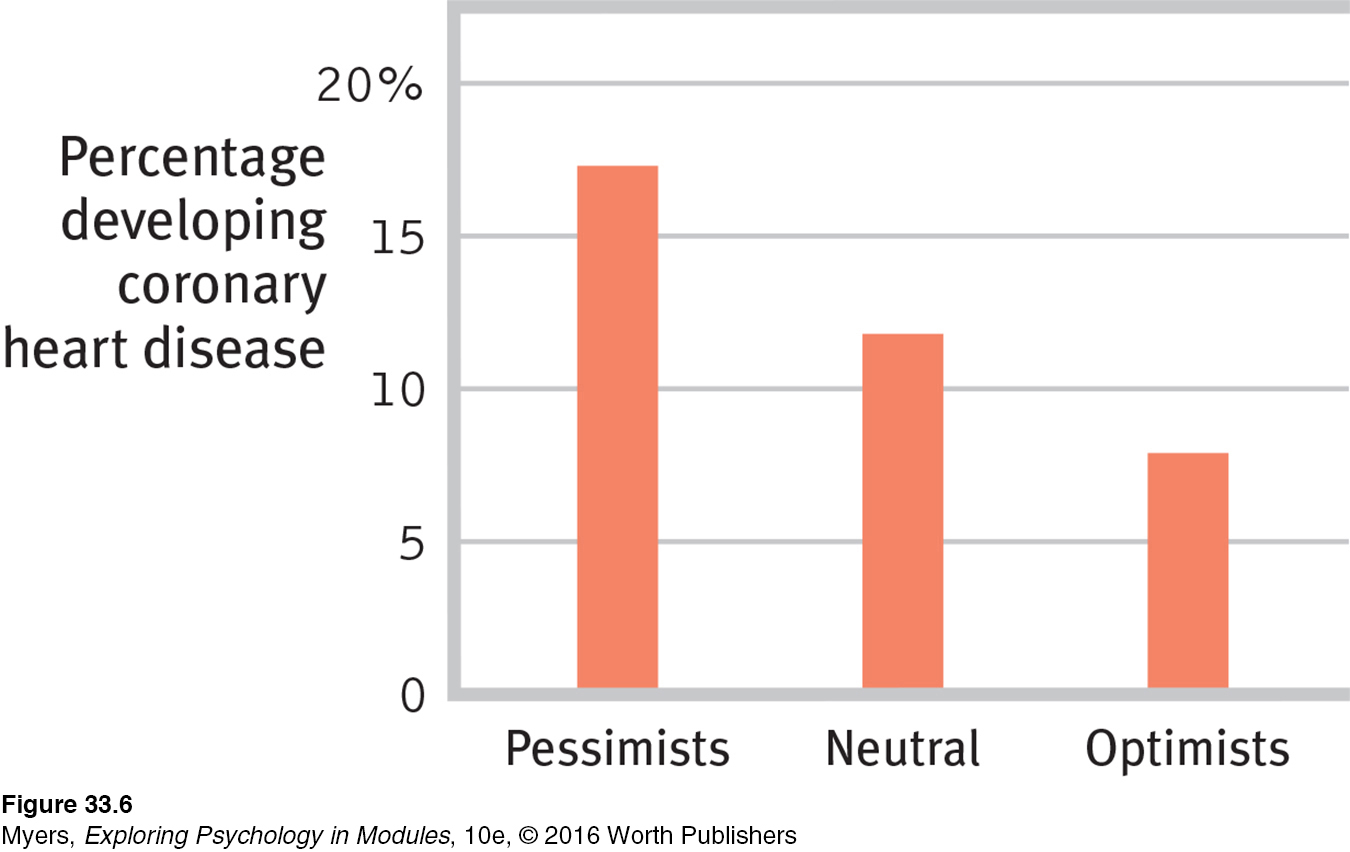

EFFECTS OF PESSIMISM AND DEPRESSION Pessimism seems to be similarly toxic. Laura Kubzansky and her colleagues (2001) studied 1306 initially healthy men who a decade earlier had scored as optimists, pessimists, or neither. Even after other risk factors such as smoking had been ruled out, pessimists were more than twice as likely as optimists to develop coronary heart disease (FIGURE 33.6). Happy people tend to be healthier and to outlive their unhappy peers (Diener & Chan, 2011; Siahpush et al., 2008). Even a big, happy smile predicts longevity, as researchers discovered when they examined the photographs of 150 Major League Baseball players who had appeared in the 1952 Baseball Register and had died by 2009 (Abel & Kruger, 2010). On average, the nonsmilers had died at 73, compared with an average 80 years for those with a broad, genuine smile. People with broad smiles tend to have extensive social networks, which predict longer life (Hertenstein, 2009).

“A cheerful heart is a good medicine, but a downcast spirit dries up the bones.”

Proverbs 17:22

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

Depression, too, can be lethal. The accumulated evidence suggests that “depression substantially increases the risk of death, especially death by unnatural causes and cardiovascular disease” (Wulsin et al., 1999). In one study, nearly 4000 English adults (ages 52 to 79) provided mood reports from a single day. Compared with those in a good mood on that day, those in a blue mood were twice as likely to be dead five years later (Steptoe & Wardle, 2011). After following 63,469 women over a dozen years, researchers found more than a doubled rate of heart attack death among those who initially scored as depressed (Whang et al., 2009). In the years following a heart attack, people with high depression scores were four times more likely than their low-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Anger Management

33-

When we face a threat or challenge, fear triggers flight but anger triggers fight—

Individualist cultures encourage people to vent their rage. Such advice is seldom heard in cultures where people’s identity is centered more on the group. People who keenly sense their interdependence see anger as a threat to group harmony (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In Tahiti, for instance, people learn to be considerate and gentle. In Japan, from infancy on, angry expressions are less common than in Western cultures, where in recent politics, anger seems all the rage.

catharsis in psychology, the idea that “releasing” aggressive energy (through action or fantasy) relieves aggressive urges.

The Western vent-

However, catharsis usually fails to cleanse our rage. More often, expressing anger breeds more anger. For one thing, it may provoke further retaliation, causing a minor conflict to escalate into a major confrontation. For another, expressing anger can magnify anger. As behavior feedback research indicates, acting angry can make us feel angrier (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). In one study, people who had been provoked were asked to wallop a punching bag while ruminating about the person who had angered them. Later, when given a chance for revenge, they became even more aggressive (Bushman, 2002).

Angry outbursts that temporarily calm us may also become reinforcing and therefore habit forming. If stressed managers find they can drain off some of their tension by berating an employee, then the next time they feel irritated and tense they may be more likely to explode again.

What are some better ways to manage anger? Experts offer three suggestions:

Wait. You can reduce the level of physiological arousal of anger by waiting. “It is true of the body as of arrows,” noted Carol Tavris (1982), “what goes up must come down. Any emotional arousal will simmer down if you just wait long enough.”

Find a healthy distraction or support. Calm yourself by exercising, playing an instrument, or talking it through with a friend. Brain scans show that ruminating inwardly about why you are angry serves only to increase amygdala bloodflow (Fabiansson et al., 2012).

Distance yourself. Try to move away from the situation mentally, as if you are watching it unfold from a distance. Self-

distancing reduces rumination, anger, and aggression (Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Mischkowski et al., 2012; White et al., 2015).

Anger is not always wrong. Used wisely, it can communicate strength and competence (Tiedens, 2001). Anger also motivates people to take action and achieve goals (Aarts & Custers, 2012). Controlled expressions of anger are more adaptive than either hostile outbursts or pent-

What if someone’s behavior really hurts you, and you cannot resolve the conflict? Research commends the age-

“Venting to reduce anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire.”

Researcher Brad Bushman (2002)

“Anger will never disappear so long as thoughts of resentment are cherished in the mind.”

The Buddha, 500 B.C.E.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which one of the following is an effective strategy for reducing angry feelings?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

STRESS AND INFLAMMATION Depressed people tend to smoke more and exercise less (Whooley et al., 2008), but stress itself is also disheartening:

When following 17,415 middle-

aged American women, researchers found an 88 percent increased risk of heart attacks among those facing significant work stress (Slopen et al., 2010). In Denmark, a study of 12,116 female nurses found that those reporting “much too high” work pressures had a 40 percent increased risk of heart disease (Allesøe et al., 2010).

In the United States, a 10-

year study of middle- aged workers found that involuntary job loss more than doubled their risk of a heart attack (Gallo et al., 2006).

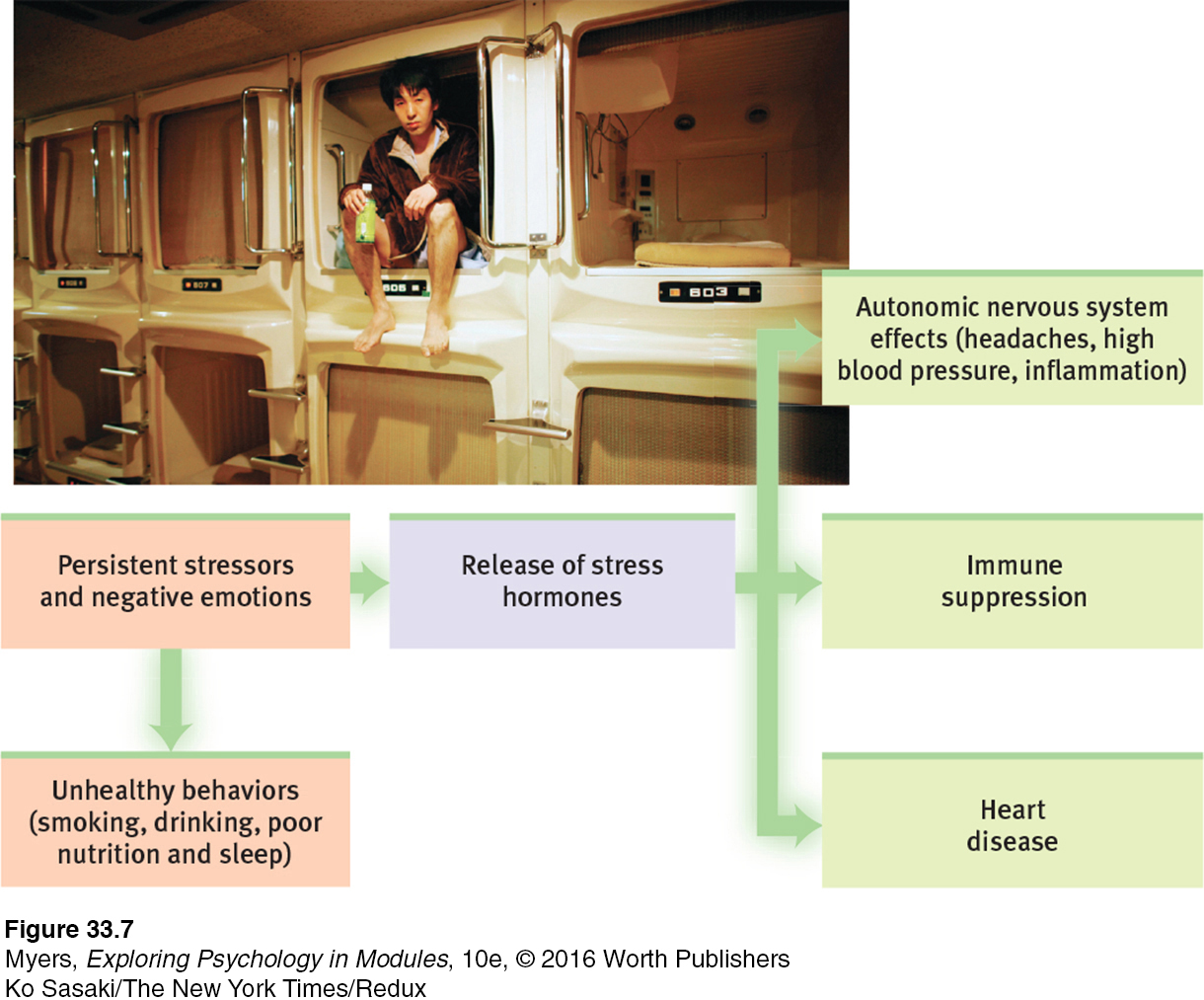

Both heart disease and depression may result when stress triggers blood vessel inflammation (Matthews, 2005; Miller & Blackwell, 2006). As the body focuses its energies on fleeing or fighting a threat, stress hormones boost the production of proteins that contribute to inflammation. Persistent inflammation can lead to asthma or clogged arteries and can worsen depression.

We can view the stress effect on our disease resistance as a price we pay for the benefits of stress (FIGURE 33.7). Stress invigorates our lives by arousing and motivating us. An unstressed life would hardly be challenging or productive.

* * *

Traditionally, people have thought about their health only when something goes wrong—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which component of the Type A personality has been linked most closely to coronary heart disease?

Question

How does Type D personality differ from Type A?