34.1 Coping With Stress

34-

coping alleviating stress using emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods.

Stressors are unavoidable. This fact, coupled with the fact that persistent stress correlates with heart disease, depression, and lowered immunity, gives us a clear message: We need to learn to cope with the stress in our lives, alleviating it with emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods.

problem-focused coping attempting to alleviate stress directly—

emotion-focused coping attempting to alleviate stress by avoiding or ignoring a stressor and attending to emotional needs related to our stress reaction.

Some stressors we address directly, with problem-focused coping. If our impatience leads to a family fight, we may go directly to that family member to work things out. We tend to use problem-

When challenged, some of us tend to respond with problem-

Personal Control

34-

Picture the scene: Two rats receive simultaneous shocks. One can turn a wheel to stop the shocks. The helpless rat, but not the wheel turner, becomes more susceptible to ulcers and lowered immunity to disease (Laudenslager & Reite, 1984). In humans, too, uncontrollable threats trigger the strongest stress responses (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

learned helplessness the hopelessness and passive resignation an animal or person learns when unable to avoid repeated aversive events.

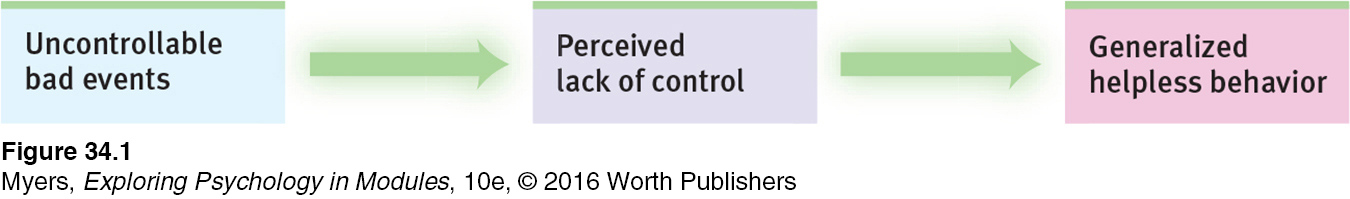

At times, we all feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our control. Martin Seligman and his colleagues have shown that for some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (FIGURE 34.1 below). In one series of experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). Later, when placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control and easily escaped the shocks in the new situation (Seligman & Maier, 1967). In other experiments, people have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Perceiving a loss of control, we become more vulnerable to ill health. A famous study of elderly nursing home residents with little perceived control over their activities found that they declined faster and died sooner than those given more control (Rodin, 1986). Workers able to adjust office furnishings and control interruptions and distractions in their work environment have experienced less stress (O’Neill, 1993). Such findings may help explain why British executives have tended to outlive those in clerical or laboring positions, and why Finnish workers with low job stress have been less than half as likely to die of stroke or heart disease as those with a demanding job and little control. The more control workers have, the longer they live (Bosma et al., 1997, 1998; Kivimaki et al., 2002; Marmot et al., 1997).

Increasing control—

Control also helps explain a link between economic status and longevity (Jokela et al., 2009). In one study of 843 grave markers in an old cemetery in Glasgow, Scotland, those with the costliest, highest pillars (indicating the most affluence) tended to have lived the longest (Carroll et al., 1994). Likewise, American presidents, who are generally wealthy and well-

Why does perceived loss of control predict health problems? Because losing control provokes an outpouring of stress hormones. When rats cannot control shock or when humans or other primates feel unable to control their environment, stress hormone levels rise, blood pressure increases, and immune responses drop (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). Captive animals experience more stress and are more vulnerable to disease than their wild counterparts (Roberts, 1988). Human studies confirm that stress increases when we lack control. The greater nurses’ workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—

INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL LOCUS OF CONTROL If experiencing a loss of control can be stressful and unhealthy, do people who generally perceive they have control of their lives enjoy better health? Consider your own perceptions of control. Do you believe that your life is beyond your control? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That being a success is a matter of hard work? Did your parents influence your feelings of control? Did your culture?

external locus of control the perception that chance or outside forces beyond our personal control determine our fate.

internal locus of control the perception that we control our own fate.

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control. On one side are those who have what psychologist Julian Rotter called an external locus of control—the perception that chance or outside forces control their fate. On the other side are those who perceive an internal locus of control, who believe they control their own destiny. In study after study, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed than did the “externals” (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In one long-

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will, or that we control our own willpower. Studies show that people who believe in their freedom learn better, perform better at work, behave more helpfully, and have a stronger desire to punish rule breakers (Clark et al., 2014; Job et al., 2010; Stillman et al., 2010).

Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now express an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders in young people (Twenge et al., 2010).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

To cope with stress when we feel in control of our world, we tend to use -focused (emotion/problem) strategies. To cope with stress when we believe we cannot change a situation, we tend to use -focused (emotion/problem) strategies.

DEPLETING AND STRENGTHENING SELF-

34-

self-control the ability to control impulses and delay short-

Self-control is the ability to control impulses and delay short-

Self-

Exercising willpower decreases neural activation in brain regions associated with mental control (Wagner et al., 2013). Might sugar provide a sweet solution to self-

Researchers do not encourage candy bar diets to improve self-

The decreased mental energy after exercising self-

The point to remember: Develop self-

Explanatory Style: Optimism Versus Pessimism

34-

In The How of Happiness, social psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy, who has lived a hard life. His dad and best friend both died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s first wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these misfortunes, Randy has a sunny disposition. He remarried and enjoys being the stepfather to three boys. His work is rewarding. Randy says he survived his life challenges by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

Randy’s story illustrates how our outlook—

Optimistic students have also tended to get better grades because they often respond to setbacks with the hopeful attitude that effort, good study habits, and self-

Consider the consistency and startling magnitude of the optimism and positive emotions factor in several other studies:

When Finnish researchers followed 2428 men for up to a decade, the number of deaths among those with a bleak, hopeless outlook was more than double that found among their optimistic counterparts (Everson et al., 1996). American researchers found the same when following 4256 Vietnam-

era veterans (Phillips et al., 2009). A now-

famous study followed up on 180 Catholic nuns who had written brief autobiographies at about 22 years of age and had thereafter lived similar lifestyles. Those who had expressed happiness, love, and other positive feelings in their autobiographies lived an average 7 years longer than their more dour counterparts (Danner et al., 2001). By age 80, some 54 percent of those expressing few positive emotions had died, as had only 24 percent of the most positive spirited. Optimists not only live long lives, but they maintain a positive view as they approach the end of their lives. One study followed more than 68,000 American women, ages 50 to 79 years, for nearly two decades (Zaslavsky et al., 2015). As death grew nearer, the optimistic women tended to feel more life satisfaction than did the pessimistic women.

“The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds; and the pessimist fears this is true.”

James Branch Cabell, The Silver Stallion, 1926

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. With identical twins, if one is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Bates, 2015; Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-

The good news is that all of us, even the most pessimistic, can learn to become more optimistic. Compared with a control group of pessimists who simply kept diaries of their daily activities, pessimists in a skill-

Social Support

34-

Social support—

Close relationships have also predicted health. People are less likely to die early if supported by close relationships (Shor et al., 2013; Uchino, 2009). When Brigham Young University researchers combined data from 70 studies of 3.4 million people worldwide, they confirmed a striking effect of social support (Holt-

To combat social isolation, we need to do more than collect lots of acquaintances. We need people who genuinely care about us (Cacioppo et al., 2014; Hawkley et al., 2008). Some fill this need by connecting with friends, family, co-

What explains the link between social support and health? Are middle-

Social support calms us and reduces blood pressure and stress hormones. Numerous studies support this finding (Hostinar et al., 2014; Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held the hand of an unknown person or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, women holding their husband’s hand showed less activity in threat-

Social support fosters stronger immune functioning. Volunteers in studies of resistance to cold viruses showed this benefit (Cohen et al., 1997, 2004). Healthy volunteers inhaled nasal drops laden with a cold virus and were quarantined and observed for five days. (In these experiments, more than 600 volunteers received $800 each to endure this experience.) Age, race, sex, and health habits being equal, those with the most social ties were least likely to catch a cold. If they did catch one, they produced less mucus. People whose daily life included frequent hugs likewise experienced fewer cold symptoms and less symptom severity (Cohen et al., 2015). More sociability meant less susceptibility. The cold fact is that the effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at!

Close relationships give us an opportunity for “open heart therapy,” a chance to confide painful feelings (Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about a stressful event can temporarily arouse us, but in the long run it calms us, by calming limbic system activity (Lieberman et al., 2007; Mendolia & Kleck, 1993). In one study, 33 Holocaust survivors spent two hours recalling their experiences, many in intimate detail never before disclosed (Pennebaker et al., 1989). In the weeks following, most watched a video of their recollections and showed it to family and friends. Those who were most self-

“Woe to one who is alone and falls and does not have another to help.”

Ecclesiastes 4:10

Suppressing emotions can be detrimental to physical health. When psychologist James Pennebaker (1985) surveyed more than 700 undergraduate women, some of them reported a traumatic childhood sexual experience. The sexually abused women—

Even writing about personal traumas in a diary can help (Burton & King, 2008; Hemenover, 2003; Lyubomirsky et al., 2006). In an analysis of 633 trauma victims, writing therapy was as effective as psychotherapy in reducing psychological trauma (van Emmerik et al., 2013). In another experiment, volunteers who wrote trauma diaries had fewer health problems during the ensuing four to six months (Pennebaker, 1990). As one participant explained, “Although I have not talked with anyone about what I wrote, I was finally able to deal with it, work through the pain instead of trying to block it out. Now it doesn’t hurt to think about it.”

If we are aiming to exercise more, drink less, quit smoking, or attain a healthy weight, our social ties can tug us away from or toward our goal. If you are trying to achieve some goal, think about whether your social network can help or hinder you. That social net covers not only the people you know but friends of your friends, and friends of their friends. That’s three degrees of separation between you and the most remote people. Within that network, others can influence your thoughts, feelings, and actions without your awareness (Christakis & Fowler, 2009).