35.2 Social Influence

Social psychology’s great lesson is the enormous power of social influence. This influence can be seen in our conformity, our obedience to authority, and our group behavior. Suicides, bomb threats, airplane hijackings, and UFO sightings all have a curious tendency to come in clusters. On campus, jeans are the dress code; on New York’s Wall Street or London’s Bond Street, dress suits are the norm. When we know how to act, how to groom, how to talk, life functions smoothly. Armed with social influence principles, advertisers, fundraisers, and campaign workers aim to sway our decisions to buy, to donate, to vote. Isolated with others who share their grievances, dissenters may gradually become rebels, and rebels may become terrorists. We’ll start by considering the nature of our cultural influences. Then we will examine the pull of our social strings. How strong are they? How do they operate? When do we break them?

“Have you ever noticed how one example—

Marian Wright Edelman, The Measure of Our Success, 1992

Cultural Influences

35-

Compared with the narrow path taken by flies, fish, and foxes, the road along which environment drives us is wider. The mark of our species—

culture the enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next.

Culture is the behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988; Cohen, 2009). Human nature, noted Roy Baumeister (2005), seems designed for culture. We are social animals, but more. Wolves are social animals; they live and hunt in packs. Ants are incessantly social, never alone. But “culture is a better way of being social,” observed Baumeister. Wolves function pretty much as they did 10,000 years ago. We enjoy things that were unknown to most of our century-

We can thank our culture’s mastery of language for this preservation of innovation. The division of labor also helps. Although two lucky people get their names on the cover of this book (which transmits accumulated cultural wisdom), the product actually results from the coordination and commitment of a gifted team of people, no one of whom could produce it alone.

Across cultures, we differ in our language, our monetary systems, our sports, even which side of the road we drive on. But beneath these differences is our great similarity—

VARIATION ACROSS CULTURES We see our adaptability in cultural variations among our beliefs and our values, in how we nurture our children and bury our dead, and in what we wear (or whether we wear anything at all). We are ever mindful that the readers of this book are culturally diverse. You and your ancestors reach from Australia to Africa and from Singapore to Sweden.

norm an understood rule for accepted and expected behavior. Norms prescribe “proper” behavior.

Riding along with a unified culture is like running with the wind: As it carries us along, we hardly notice it. When we try running against the wind we feel its force. Face to face with a different culture, we become aware of the cultural winds. Stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait, American and European soldiers were reminded how liberal their home cultures were. Each cultural group evolves its own norms—rules for accepted and expected behavior. The British have a norm for orderly waiting in line. Many South Asians use only the right hand’s fingers for eating. Sometimes social expectations seem oppressive: “Why should it matter what I wear?” Yet, norms grease the social machinery and can free us from self-

When cultures collide, their differing norms often befuddle. Should we greet people by shaking hands, bowing, or kissing one or both cheeks? Knowing what sorts of gestures and compliments are culturally appropriate helps us avoid accidental insults and embarrassment.

VARIATION OVER TIME Like biological creatures, cultures vary and compete for resources, and thus evolve over time (Mesoudi, 2009). Consider how rapidly cultures may change. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1342–

But some changes seem not so wonderfully positive. Had you fallen asleep in the United States in 1960 and awakened today, you would open your eyes to a culture with more divorce and depression. You would also find North Americans—

Whether we love or loathe these changes, we cannot fail to be impressed by their breathtaking speed. And we cannot explain them by changes in the human gene pool, which evolves far too slowly to account for high-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is culture, and how does its transmission distinguish us from other social animals?

Conformity: Complying With Social Pressures

35-

AUTOMATIC MIMICRY Fish swim in schools. Birds fly in flocks. And humans, too, tend to go with their group, to think what it thinks and do what it does. Behavior is contagious. Chimpanzees are more likely to yawn after observing another chimpanzee yawn (Anderson et al., 2004). Ditto for humans. If one of us yawns, laughs, coughs, scratches an itch, stares at the sky, or checks a cell phone, others in our group will often do the same (Holle et al., 2009). Yawn mimicry can also occur across species: Dogs more often yawn after observing their owners’ yawn (Silva et al., 2012). Even just reading about yawning increases people’s yawning (Provine, 2012), as perhaps you have noticed?

Like the chameleon lizards that take on the color of their surroundings, we humans take on the emotional tones of those around us. Just hearing someone reading a neutral text in either a happy-

Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh captured this automatic mimicry, which they call the chameleon effect (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). They had students work in a room alongside another person, who was actually a “confederate” working for the experimenters. Sometimes the confederates rubbed their own face. Sometimes they shook their foot. Sure enough, the students tended to rub their face with the face-

Automatic mimicry helps us to empathize—

Suggestibility and mimicry sometimes lead to tragedy. In the eight days following the 1999 shooting rampage at Colorado’s Columbine High School, every U.S. state except Vermont experienced threats of copycat violence. Pennsylvania alone recorded 60 such threats (Cooper, 1999). Sociologist David Phillips and his colleagues (1985, 1989) found that suicides, too, sometimes increase following a highly publicized suicide. In the wake of screen idol Marilyn Monroe’s suicide on August 5, 1962, for example, the number of suicides in the United States exceeded the usual August count by 200.

“When I see synchrony and mimicry—

Primatologist Frans de Waal “The Empathy Instinct,” 2009

What causes behavior clusters? Do people act similarly because of their influence on one another? Or because they are simultaneously exposed to the same events and conditions? Seeking answers to such questions, social psychologists have conducted experiments on group pressure and conformity.

conformity adjusting our behavior or thinking to coincide with a group standard.

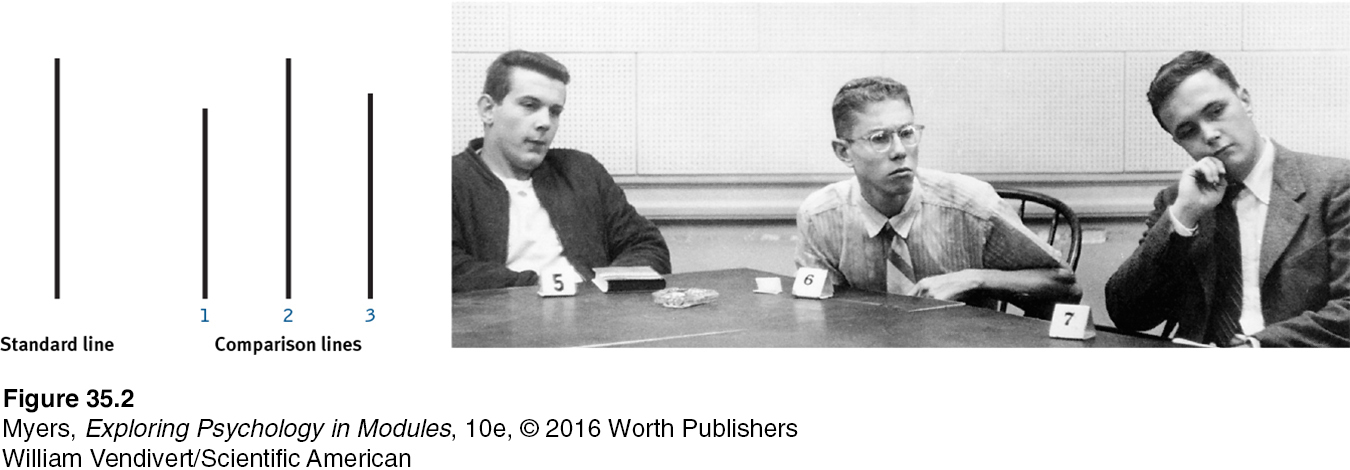

CONFORMITY AND SOCIAL NORMS Suggestibility and mimicry are subtle types of conformity—adjusting our behavior or thinking toward some group standard. To study conformity, Solomon Asch (1955) devised a simple test. Imagine yourself as a participant in what you believe is a study of visual perception. You arrive in time to take a seat at a table with five other people. The experimenter asks the group to state, one by one, which of three comparison lines is identical to a standard line. You see clearly that the answer is Line 2, and you await your turn to say so. Your boredom begins to show when the next set of lines proves equally easy.

Now comes the third trial, and the correct answer seems just as clear-

In Asch’s experiments, college students, answering questions alone, erred less than 1 percent of the time. But what about when several others—

Later investigations have not always found as much conformity as Asch found, but they have revealed that we are more likely to conform when we

are made to feel incompetent or insecure.

are in a group with at least three people.

are in a group in which everyone else agrees. (If just one other person disagrees, the odds of our disagreeing greatly increase.)

admire the group’s status and attractiveness.

have not made a prior commitment to any response.

know that others in the group will observe our behavior.

are from a culture that strongly encourages respect for social standards.

Why do we so often think what others think and do what they do? Why, in college residence halls, do students’ attitudes become more similar to those living near them (Cullum & Harton, 2007)? Why, when asked controversial questions, are students’ answers more diverse when using anonymous electronic clickers than when publicly raising hands (Stowell et al., 2010)? Why do we clap when others clap, eat as others eat, believe what others believe, say what others say, even see what others see?

normative social influence influence resulting from a person’s desire to gain approval or avoid disapproval.

Frequently, we conform to avoid rejection or to gain social approval (Williams and Sommer, 1997). In such cases, we are responding to normative social influence. We are sensitive to social norms—understood rules for accepted and expected behavior—

informational social influence influence resulting from one’s willingness to accept others’ opinions about reality.

At other times, we conform because we want to be accurate. Groups provide information, and only an uncommonly stubborn person will never listen to others. “Those who never retract their opinions love themselves more than they love truth,” observed Joseph Joubert, an eighteenth-

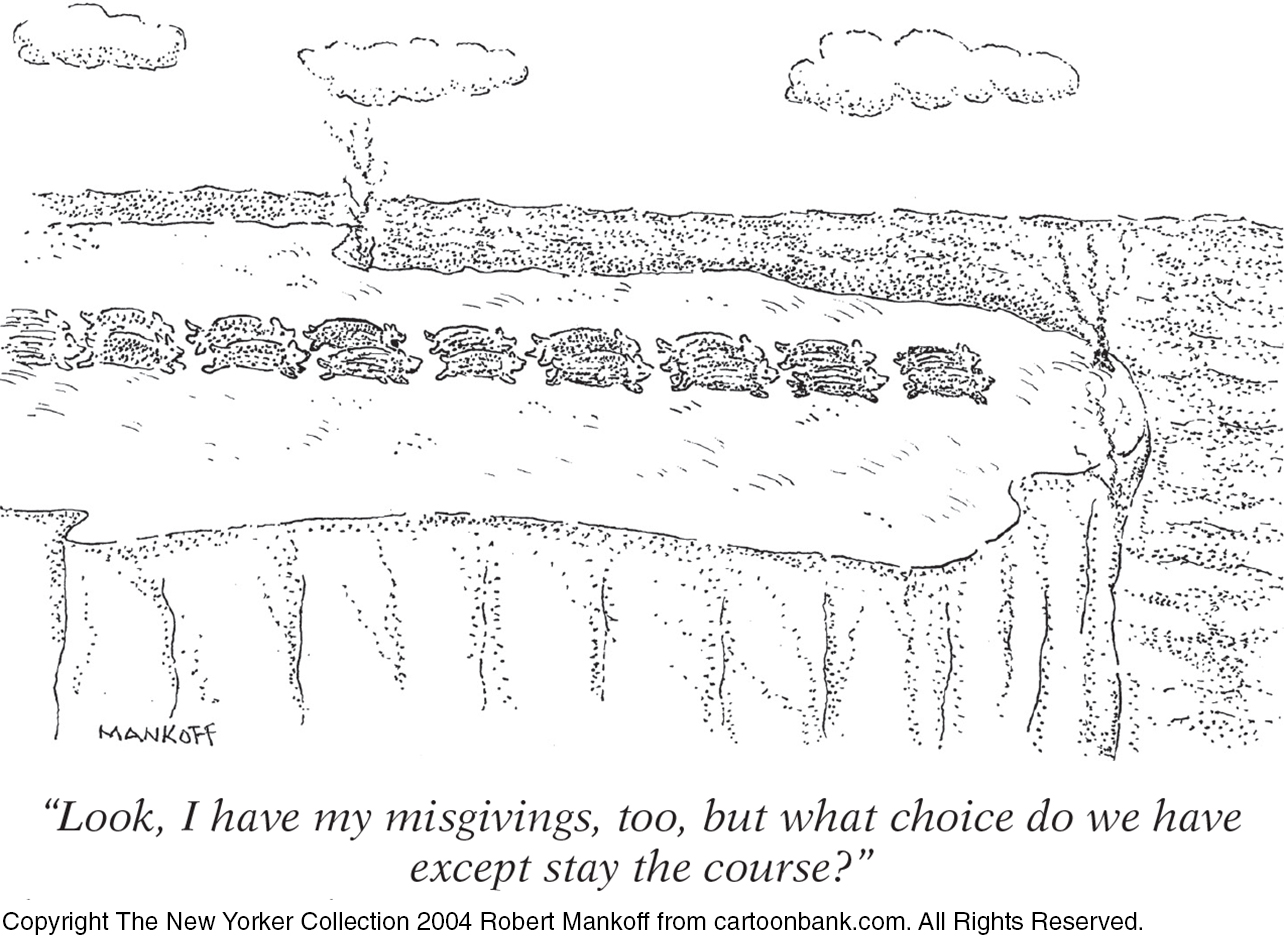

Like humans, migrating and herding animals conform for both informational and normative reasons (Claidière & Whiten, 2012). Following others is informative: Compared with solo geese, a flock of geese migrate more accurately. (There is wisdom in the crowd.) But staying with the herd also sustains group membership.

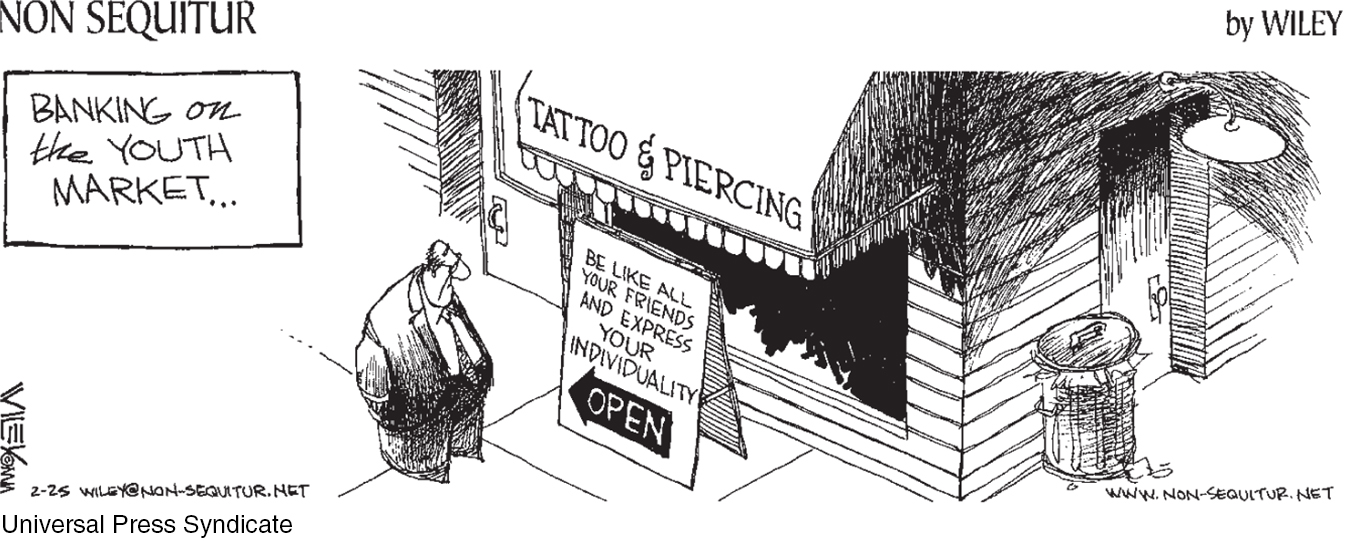

Is conformity good or bad? The answer depends partly on our culturally influenced values. Western Europeans and people in most English-

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which of the following strengthens conformity to a group?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Obedience: Following Orders

35-

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974), a high school classmate of Philip Zimbardo and later a student of Solomon Asch, knew that people often give in to social pressures. But how would they respond to outright commands? To find out, he undertook what became social psychology’s most famous and controversial experiments (Benjamin & Simpson, 2009).

See LaunchPad’s Video: Research Ethics below for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Research Ethics below for a helpful tutorial animation.

Imagine yourself as one of the nearly 1000 people who took part in Milgram’s 20 experiments. You respond to an advertisement for participants in a Yale University psychology study of the effect of punishment on learning. Professor Milgram’s assistant asks you and another person to draw slips from a hat to see who will be the “teacher” and who will be the “learner.” Because (unknown to you) both slips say “teacher,” you draw a “teacher” slip and are asked to sit down in front of a machine, which has a series of labeled switches. The supposed learner, a mild and submissive-

The experiment begins, and you deliver the shocks after the first and second wrong answers. If you continue, you hear the learner grunt when you flick the third, fourth, and fifth switches. After you activate the eighth switch (“120 Volts—

If you obey, you hear the learner shriek in apparent agony as you continue to raise the shock level after each new error. After the 330-

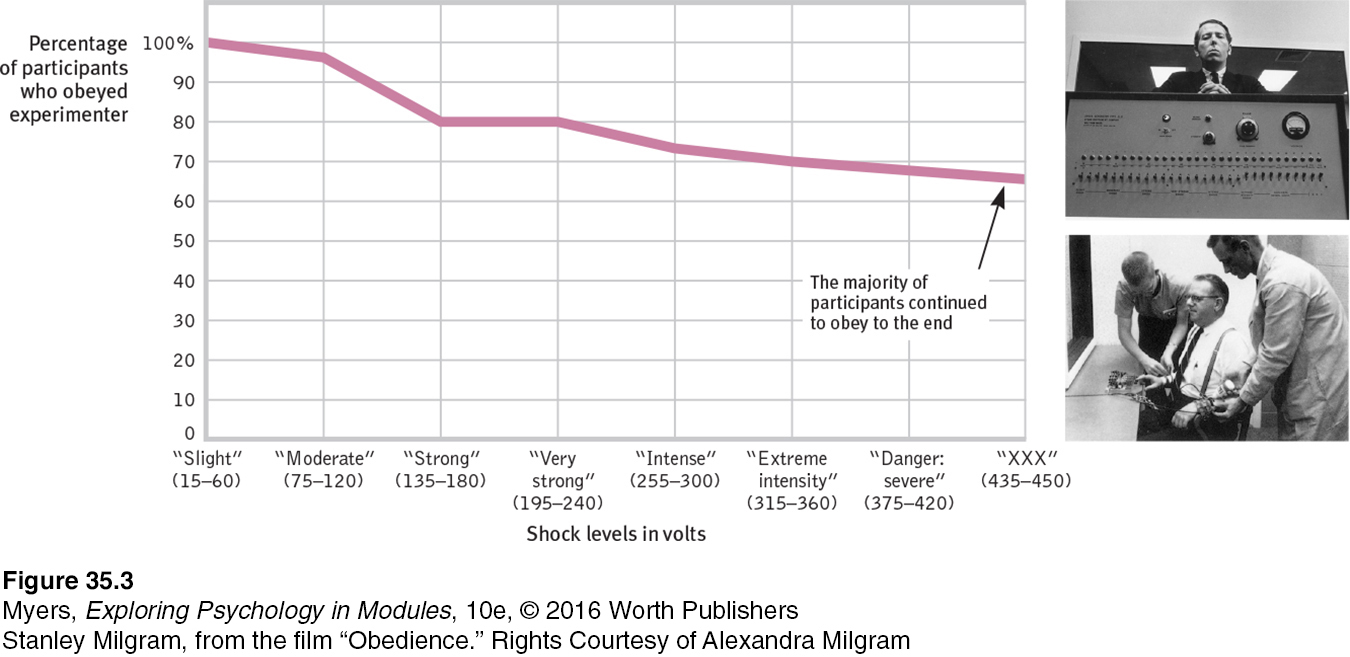

Would you follow the experimenter’s commands to shock someone? At what level would you refuse to obey? Before undertaking the experiments, Milgram asked nonparticipating people what they would do. Most people were sure they would stop soon after the learner first indicated pain, certainly before he shrieked in agony. Forty psychiatrists agreed with that prediction when Milgram asked them. Were the predictions accurate? Not even close. When Milgram conducted the experiment with other men aged 20 to 50, he was astonished. More than 60 percent complied fully—

Cultures change over time. Researchers wondered if Milgram’s results could be explained by the 1960s American mind-

Did the teachers figure out the hoax—

Milgram’s use of deception and stress triggered a debate over his research ethics. In his own defense, Milgram pointed out that, after the participants learned of the deception and actual research purposes, virtually none regretted taking part (though perhaps by then the participants had reduced their cognitive dissonance—

In later experiments, Milgram discovered some conditions that influence people’s behavior. When he varied the situation, full obedience ranged from 0 to 93 percent. Obedience was highest when

the person giving the orders was close at hand and was perceived to be a legitimate authority figure. Such was the case in 2005 when Temple University’s basketball coach sent a 250-

pound bench player, Nehemiah Ingram, into a game with instructions to commit “hard fouls.” Following orders, Ingram fouled out in four minutes after breaking an opposing player’s right arm. the authority figure was supported by a powerful or prestigious institution. Compliance was somewhat lower when Milgram dissociated his experiments from Yale University. People have wondered: Why, during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, did so many Hutu citizens slaughter their Tutsi neighbors? It was partly because they were part of “a culture in which orders from above, even if evil,” were understood as having the force of law (Kamatali, 2014).

the victim was depersonalized or at a distance, even in another room. Similarly, many soldiers in combat either have not fired their rifles at an enemy they can see, or have not aimed them properly. Such refusals to kill have been rare among soldiers who were operating long-

distance artillery or aircraft weapons (Padgett, 1989). Those who killed from a distance— by operating remotely piloted drones— also have suffered much less posttraumatic stress than have on- the- ground Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans (Miller, 2012a). Page 454there were no role models for defiance. “Teachers” did not see any other participant disobey the experimenter.

The power of legitimate, close-

The commander gave the recruits a chance to refuse to participate in the executions. Only about a dozen immediately refused. Within 17 hours, the remaining 485 officers killed 1500 helpless women, children, and elderly, shooting them in the back of the head as they lay face down. Hearing the victims’ pleas, and seeing the gruesome results, some 20 percent of the officers did eventually dissent, managing either to miss their victims or to wander away and hide until the slaughter was over (Browning, 1992). In real life, as in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted were the minority.

A different story played out in the French village of Le Chambon. There, villagers openly defied orders to cooperate with the “New Order”: they sheltered French Jews, who were destined for deportation to Germany, and sometimes helped them escape across the Swiss border. The villagers’ Protestant ancestors had themselves been persecuted, and their pastors taught them to “resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the Gospel” (Rochat, 1993). Ordered by police to give a list of sheltered Jews, the head pastor modeled defiance: “I don’t know of Jews, I only know of human beings.” At great personal risk, the resisters made an initial commitment to resist. Throughout the long, terrible war, they suffered poverty and were punished for their disobedience. Still, supported by their beliefs, their role models, their interactions with one another, and their own initial acts, they remained defiant to the war’s end.

LESSONS FROM THE OBEDIENCE STUDIES What do the Milgram experiments teach us about ourselves? How does flicking a shock switch relate to everyday social behavior? Psychological experiments aim not to re-

In Milgram’s experiments and their modern replications, participants were torn. Should they respond to the pleas of the victim or the orders of the experimenter? Their moral sense warned them not to harm another, yet it also prompted them to obey the experimenter and to be a good research participant. With kindness and obedience on a collision course, obedience usually won.

“I was only following orders.”

Adolf Eichmann, director of Nazi deportation of Jews to concentration camps

These experiments demonstrated that strong social influences can make people conform to falsehoods or capitulate to cruelty. Milgram saw this as the fundamental lesson of this work: “Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process” (1974, p. 6).

Focusing on the end point—

So it happens when people succumb, gradually, to evil. In any society, great evils often grow out of people’s compliance with lesser evils. The Nazi leaders suspected that most German civil servants would resist shooting or gassing Jews directly, but they found them surprisingly willing to handle the paperwork of the Holocaust (Silver & Geller, 1978). Milgram found a similar reaction in his experiments. When he asked 40 men to administer the learning test while someone else did the shocking, 93 percent complied. Cruelty does not require devilish villains. All it takes is ordinary people corrupted by an evil situation. Ordinary students may follow orders to haze initiates into their group. Ordinary employees may follow orders to produce and market harmful products. Ordinary soldiers may follow orders to punish and torture prisoners (Lankford, 2009).

“All evil begins with 15 volts.”

Philip Zimbardo, Stanford lecture, 2010

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Psychology's most famous obedience experiments, in which most participants obeyed an authority figure's demands to inflict presumed painful, dangerous shocks on an innocent participant, were conducted by social psychologist .

Question

What situations have researchers found to be most likely to encourage obedience in participants?

Group Behavior

35-

Imagine standing in a room, holding a fishing pole. Your task is to wind the reel as fast as you can. On some occasions you wind in the presence of another participant, who is also winding as fast as possible. Will the other’s presence affect your own performance?

In one of social psychology’s first experiments, Norman Triplett (1898) reported that adolescents would wind a fishing reel faster in the presence of someone doing the same thing. Although a modern reanalysis revealed that the difference was modest (Stroebe, 2012), Triplett inspired later social psychologists to study how others’ presence affects our behavior. Group influences operate both in simple groups—

social facilitation improved performance on simple or well-

SOCIAL FACILITATION Triplett’s claim—

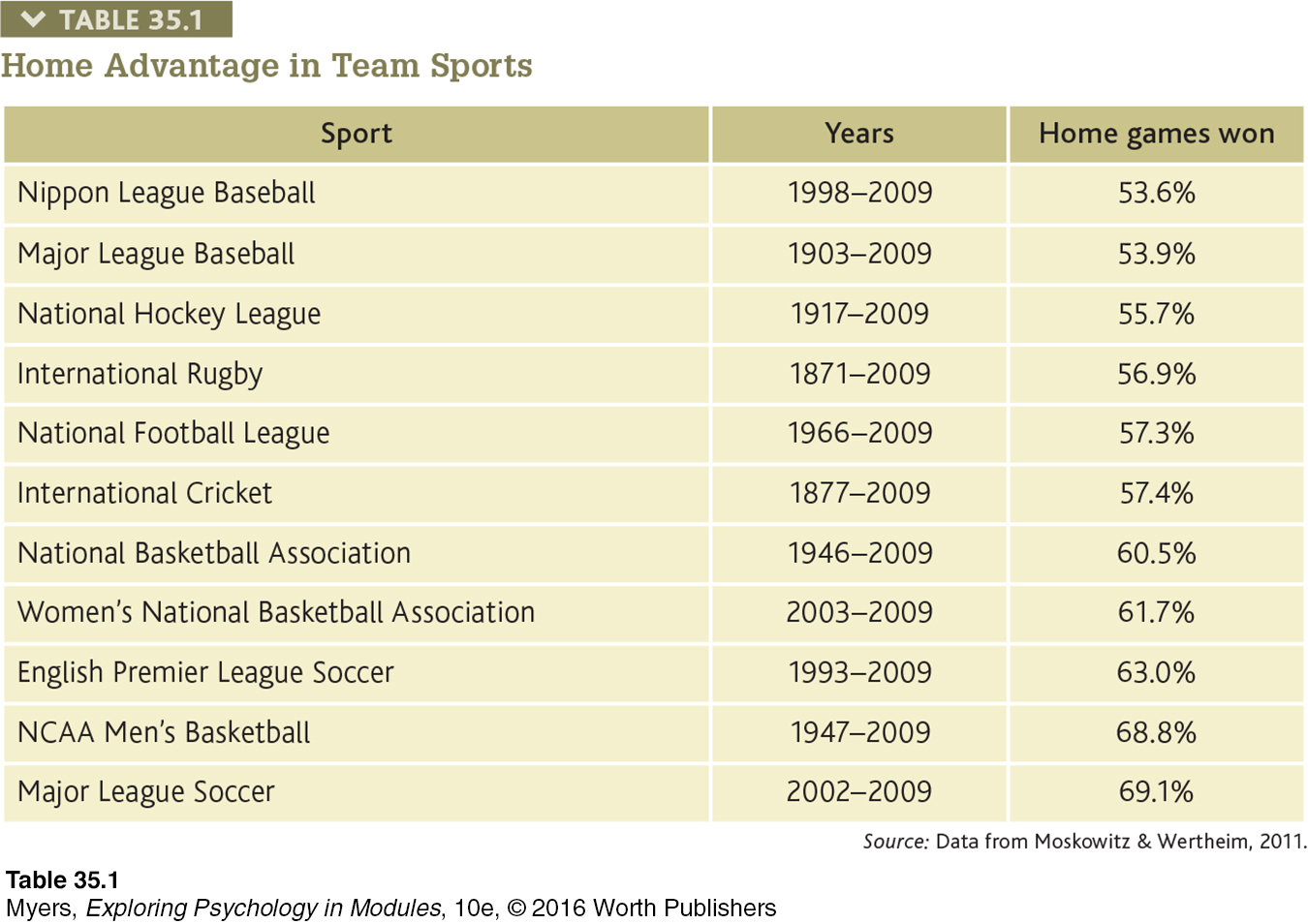

The energizing effect of an enthusiastic audience probably contributes to the home advantage that has shown up in studies of more than a quarter-

Social facilitation also helps explain a funny effect of crowding. Comedians and actors know that a “good house” is a full one. Crowding triggers arousal. Comedy routines that are mildly amusing to people in an uncrowded room seem funnier in a densely packed room (Aiello et al., 1983; Freedman & Perlick, 1979). In experiments, participants, when seated close to one another, like a friendly person even more and an unfriendly person even less (Schiffenbauer & Schiavo, 1976; Storms & Thomas, 1977). So, to ensure an energetic class or event, choose a room or set up seating that will just barely accommodate everyone.

The point to remember: What you do well, you are likely to do even better in front of an audience, especially a friendly audience. What you normally find difficult may seem all but impossible when you are being watched.

SOCIAL LOAFING Social facilitation experiments test the effect of others’ presence on performance of an individual task, such as shooting pool. But what happens when people perform as a group? In a team tug-

To find out, a University of Massachusetts research team asked blindfolded students “to pull as hard as you can” on a rope. When they fooled the students into believing three others were also pulling behind them, students exerted only 82 percent as much effort as when they knew they were pulling alone (Ingham et al., 1974). And consider what happened when blindfolded people seated in a group clapped or shouted as loudly as they could while hearing (through headphones) other people clapping or shouting loudly (Latané, 1981). When they thought they were part of a group effort, the participants produced about one-

social loafing the tendency for people in a group to exert less effort when pooling their efforts toward attaining a common goal than when individually accountable.

Bibb Latané and his colleagues (1981; Jackson & Williams, 1988) described this diminished effort as social loafing. Experiments in the United States, India, Thailand, Japan, China, and Taiwan have found social loafing on various tasks, though it was especially common among men in individualist cultures (Karau & Williams, 1993). What causes social loafing? Three things:

People acting as part of a group feel less accountable, and therefore worry less about what others think.

Group members may view their individual contributions as dispensable (Harkins & Szymanski, 1989; Kerr & Bruun, 1983).

When group members share equally in the benefits, regardless of how much they contribute, some may slack off (as you perhaps have observed on group assignments). Unless highly motivated and strongly identified with the group, people may free ride on others’ efforts.

deindividuation the loss of self-

DEINDIVIDUATION We’ve seen that the presence of others can arouse people (social facilitation), or it can diminish their feelings of responsibility (social loafing). But sometimes the presence of others does both. The uninhibited behavior that results can range from a food fight to vandalism or rioting. This process of losing self-

Deindividuation thrives, for better or for worse, in many settings. Tribal warriors who depersonalize themselves with face paints or masks are more likely than those with exposed faces to kill, torture, or mutilate captured enemies (Watson, 1973). On discussion boards, Internet bullies, who would never say “You’re so fake” to someone’s face, may hide behind anonymity. When we shed self-

Behavior in the Presence of Others: Three Phenomena

| Phenomenon | Social context | Psychological effect of others’ presence | Behavioral effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social facilitation | Individual being observed | Increased arousal | Amplified dominant behavior, such as doing better what one does well (or doing worse what is difficult) |

| Social loafing | Group projects | Diminished feelings of responsibility when not individually accountable | Decreased effort |

| Deindividuation | Group setting that fosters arousal and anonymity | Reduced self- |

Lowered self- |

* * *

We have examined the conditions under which the presence of others can motivate people to exert themselves or tempt them to free ride on the efforts of others, make easy tasks easier or difficult tasks harder, and enhance humor or fuel mob violence. Research also shows that interacting with others can similarly have both bad and good effects.

Group Polarization

35-

Over time, initial differences between groups of college and university students tend to grow. If the first-

group polarization the enhancement of a group’s prevailing inclinations through discussion within the group.

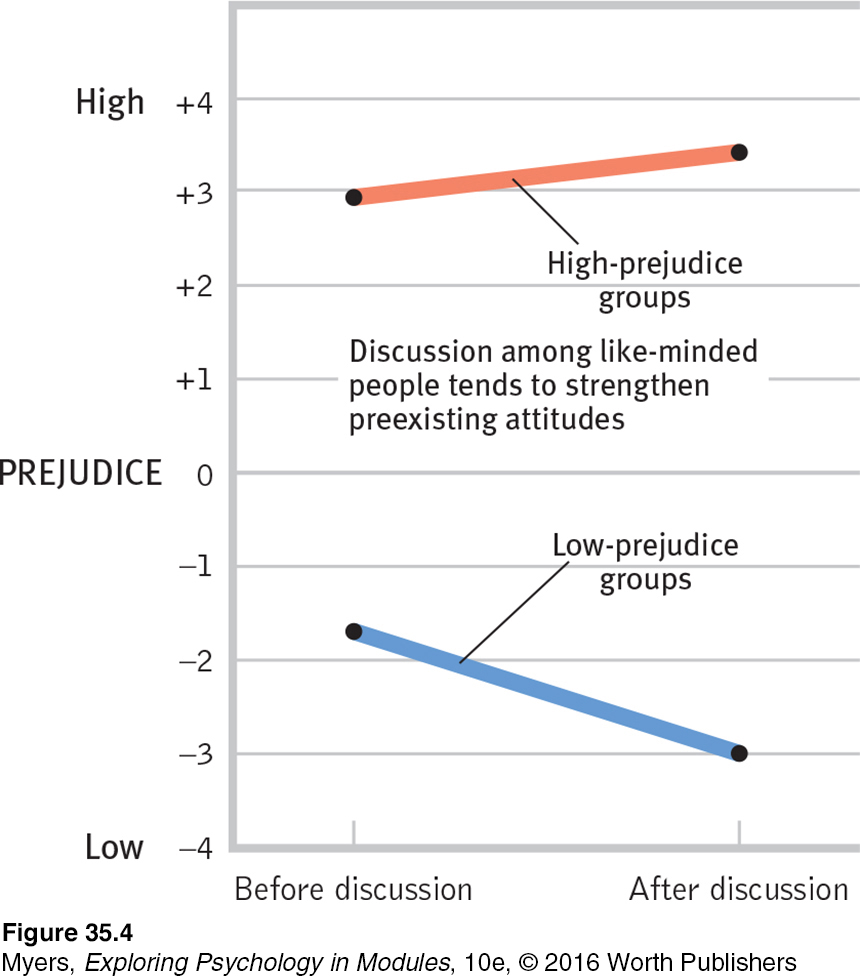

In each case, the beliefs and attitudes we bring to a group grow stronger as we discuss them with like-

Group polarization can feed extremism and even suicide terrorism. Analyses of terrorist organizations around the world reveal that the terrorist mentality does not erupt suddenly, on a whim (McCauley, 2002; McCauley & Segal, 1987; Merari, 2002). It usually begins slowly, among people who share a grievance. As they interact in isolation (sometimes with other “brothers” and “sisters” in camps) their views grow more and more extreme. Increasingly, they categorize the world as “us” against “them” (Moghaddam, 2005; Qirko, 2004). Given that the self-

“What explains the rise of fascism in the 1930s? The emergence of student radicalism in the 1960s? The growth of Islamic terrorism in the 1990s?. . . The unifying theme is simple: When people find themselves in groups of like-

Cass Sunstein, Going to Extremes, 2009

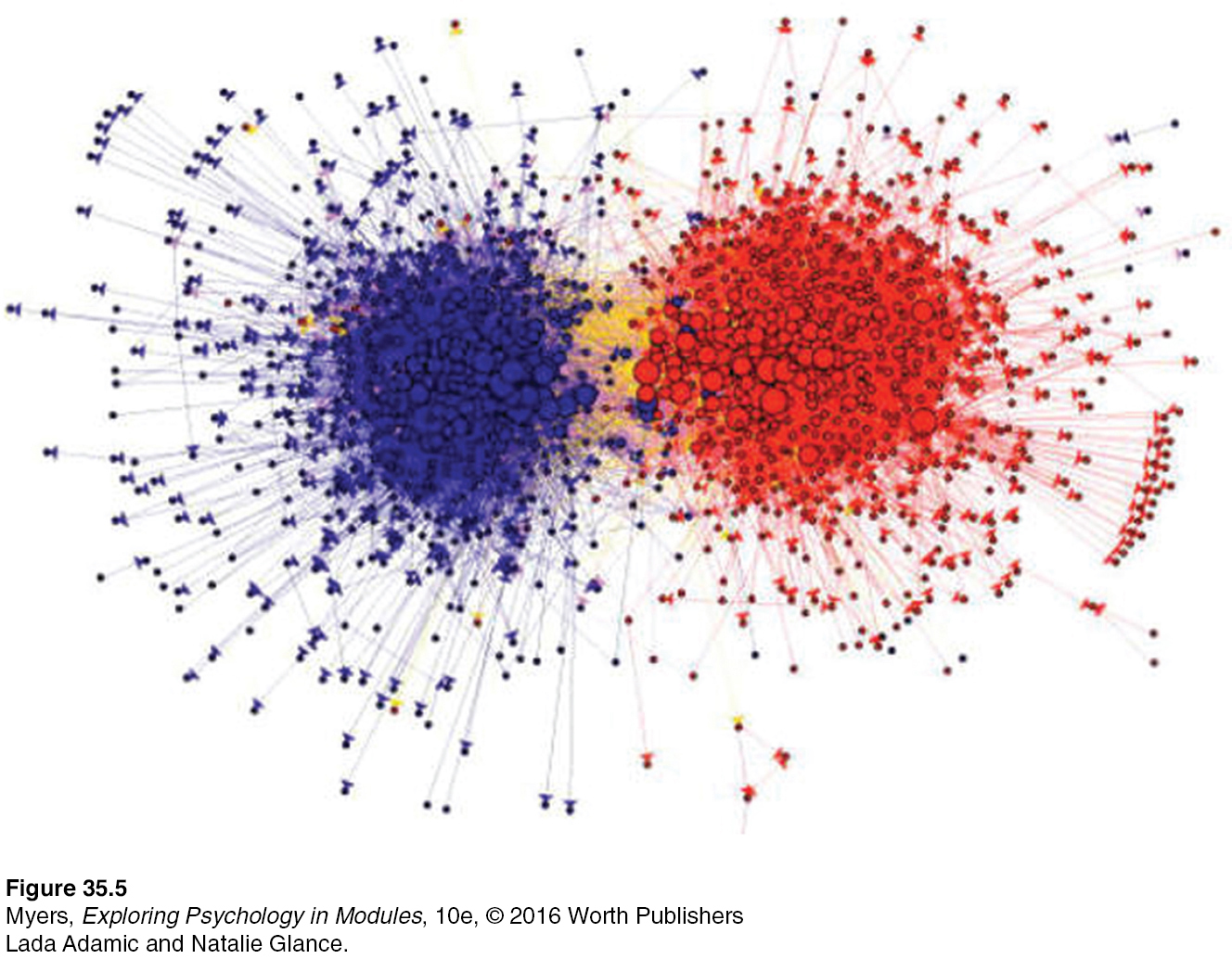

When I [DM] got my start in social psychology with experiments on group polarization, I never imagined the potential dangers, or the creative possibilities, of polarization in virtual groups. Electronic communication and social networking have created virtual town halls where people can isolate themselves from those with different perspectives. By attuning our bookmarks and social media feeds to sites that trash the views we despise, we can retreat into partisan tribes and revel in foregone conclusions. Facebook prioritizes News Feed posts that it anticipates we will like. But we ourselves have a bigger effect as we click to content we agree with and unfollow irksome friends, thus blocking those with opposing political views (Bakshy et al., 2015). People read blogs that reinforce their views, and those blogs link to kindred blogs (FIGURE 35.5). Over time, the resulting political polarization—

As the Internet connects the like-

But the Internet-

The point to remember: By connecting and magnifying the inclinations of like-

GROUPTHINK So, group interaction can influence our personal decisions. Does it ever distort important national decisions? Consider the “Bay of Pigs fiasco.” In 1961, President John F. Kennedy and his advisers decided to invade Cuba with 1400 CIA-

groupthink the mode of thinking that occurs when the desire for harmony in a decision-

Social psychologist Irving Janis (1982) studied the decision-

“One of the dangers in the White House, based on my reading of history, is that you get wrapped up in groupthink and everybody agrees with everything, and there’s no discussion and there are no dissenting views.”

Barack Obama, December 1, 2008, press conference

Later studies showed that groupthink—

“Truth springs from argument among friends.”

Philosopher David Hume, 1711–

Despite the dangers of groupthink, two heads are often better than one. Knowing this, Janis also studied instances in which U.S. presidents and their advisers collectively made good decisions, such as when the Truman administration formulated the Marshall Plan, which offered assistance to Europe after World War II, and when the Kennedy administration successfully prevented the Soviets from installing missiles in Cuba. In such instances—

“If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas.”

Attributed to dramatist George Bernard Shaw, 1856–

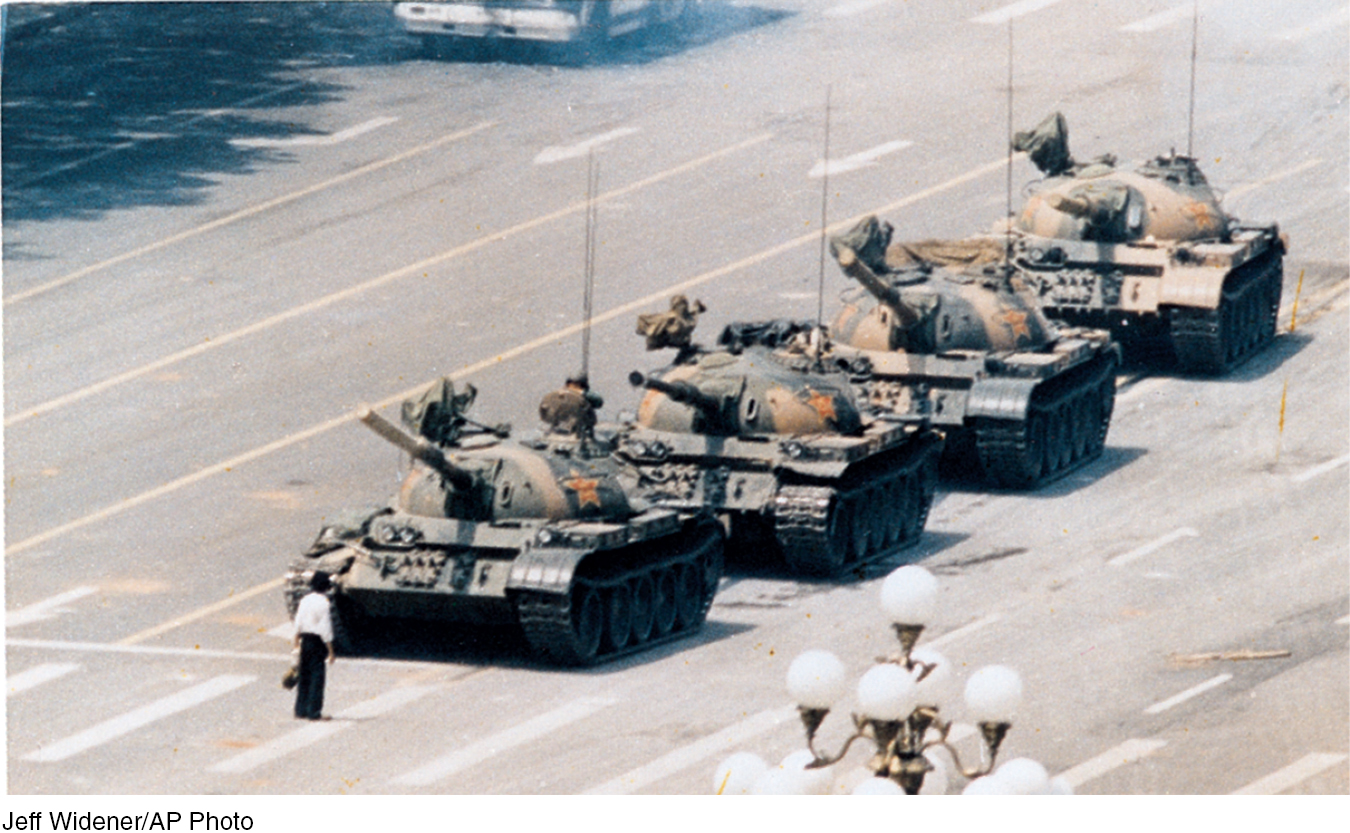

THE POWER OF INDIVIDUALS In affirming the power of social influence, we must not overlook the power of individuals. Social control (the power of the situation) and personal control (the power of the individual) interact. People aren’t billiard balls. When feeling coerced, we may react by doing the opposite of what is expected, thereby reasserting our sense of freedom (Brehm & Brehm, 1981).

Committed individuals can sway the majority and make social history. Were this not so, communism would have remained an obscure theory, Christianity would be a small Middle Eastern sect, and Rosa Parks’ refusal to sit at the back of the bus would not have ignited the U.S. civil rights movement. Technological history, too, is often made by innovative minorities who overcome the majority’s resistance to change. To many, the railroad was a nonsensical idea; some farmers even feared that train noise would prevent hens from laying eggs. People derided Robert Fulton’s steamboat as “Fulton’s Folly.” As Fulton later said, “Never did a single encouraging remark, a bright hope, a warm wish, cross my path.” Much the same reaction greeted the printing press, the telegraph, the incandescent lamp, and the typewriter (Cantril & Bumstead, 1960).

The power of one or two individuals to sway majorities is minority influence (Moscovici, 1985). In studies of groups in which one or two individuals consistently express a controversial attitude or an unusual perceptual judgment, one finding repeatedly stands out: When you are the minority, you are far more likely to sway the majority if you hold firmly to your position and don’t waffle. This tactic won’t make you popular, but it may make you influential, especially if your self-

The bottom line: The powers of social influence are enormous, but so are the powers of the committed individual. For classical music, Mozart mattered. For drama, Shakespeare mattered. For world history, Hitler and Mao—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is social facilitation, and why is it more likely to occur with a well-

Question

People tend to exert less effort when working with a group than they would alone, which is called .

Question

You are organizing a meeting of fiercely competitive political candidates and their supporters. To add to the fun, friends have suggested handing out masks of the candidates' faces for supporters to wear. What phenomenon might these masks engage?

Question

When like-minded groups discuss a topic, and the result is the strengthening of the prevailing opinion, this is called .

Question

When a group's desire for harmony overrides its realistic analysis of other options, has occurred.