38.2 The Psychodynamic Theories

psychodynamic theories view personality with a focus on the unconscious and the importance of childhood experiences.

psychoanalysis Freud’s theory of personality that attributes thoughts and actions to unconscious motives and conflicts; the techniques used in treating psychological disorders by seeking to expose and interpret unconscious tensions.

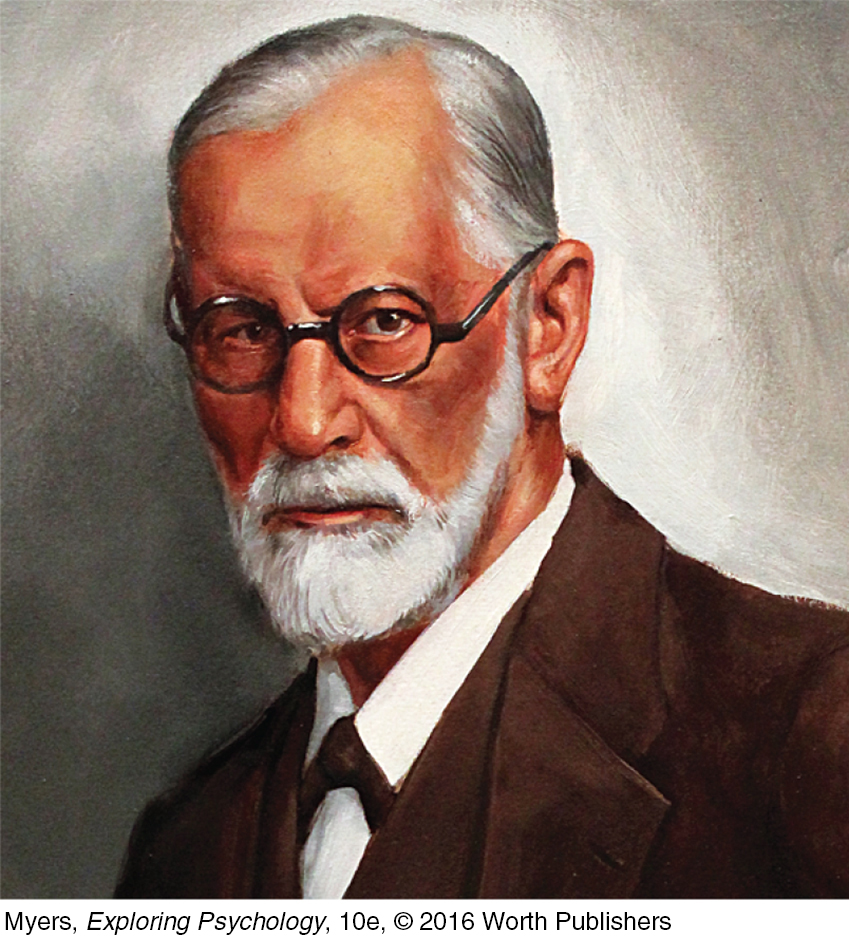

Psychodynamic theories of personality view human behavior as a dynamic interaction between the conscious mind and the unconscious mind, including associated motives and conflicts. These theories are descended from Freud’s psychoanalysis—his theory of personality and the associated treatment techniques. Freud was the first to focus clinical attention on our unconscious mind.

Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective: Exploring the Unconscious

38-

Ask 100 people on the street to name a notable deceased psychologist, suggested Keith Stanovich (1996, p. 1), and “Freud would be the winner hands down.” In the popular mind, he is to psychology what Elvis Presley is to rock music. Freud’s influence not only lingers in psychiatry and clinical psychology, but also in literary and film interpretation. Almost 9 in 10 American college courses that reference psychoanalysis have been outside of psychology departments (Cohen, 2007). Today’s psychological science is, as we will see, skeptical about many of Freud’s ideas and methods. Yet his early twentieth-

Like all of us, Sigmund Freud was a product of his times. His Victorian era was a time of tremendous discovery and scientific advancement, but it is also known today as a time of sexual repression and male dominance. Men’s and women’s roles were clearly defined, with male superiority assumed and only male sexuality generally acknowledged (discreetly).

“The female . . . acknowledges the fact of her castration, and with it, too, the superiority of the male and her own inferiority; but she rebels against this unwelcome state of affairs.”

Sigmund Freud, Female Sexuality, 1931

Long before entering the University of Vienna in 1873, young Freud showed signs of independence and brilliance. He so loved reading plays, poetry, and philosophy that he once ran up a bookstore debt beyond his means. As a teen he often took his evening meal in his tiny bedroom in order to lose no time from his studies. After medical school he set up a private practice specializing in nervous disorders. Before long, however, he faced patients whose disorders made no neurological sense. A patient might have lost all feeling in a hand—

unconscious according to Freud, a reservoir of mostly unacceptable thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. According to contemporary psychologists, information processing of which we are unaware.

free association in psychoanalysis, a method of exploring the unconscious in which the person relaxes and says whatever comes to mind, no matter how trivial or embarrassing.

Might some neurological disorders have psychological causes? Observing patients led Freud to his “discovery” of the unconscious. He speculated that lost feeling in one’s hand might be caused by a fear of touching one’s genitals; that unexplained blindness or deafness might be caused by not wanting to see or hear something that aroused intense anxiety. How might such disorders be treated? After some early unsuccessful trials with hypnosis, Freud turned to free association, in which he told the patient to relax and say whatever came to mind, no matter how embarrassing or trivial. He assumed that a line of mental dominoes had fallen from his patients’ distant past to their troubled present, and that the chain of thought revealed by free association would allow him to retrace that line into a patient’s unconscious. There, painful memories, often from childhood, could then be retrieved from the unconscious and brought into conscious awareness.

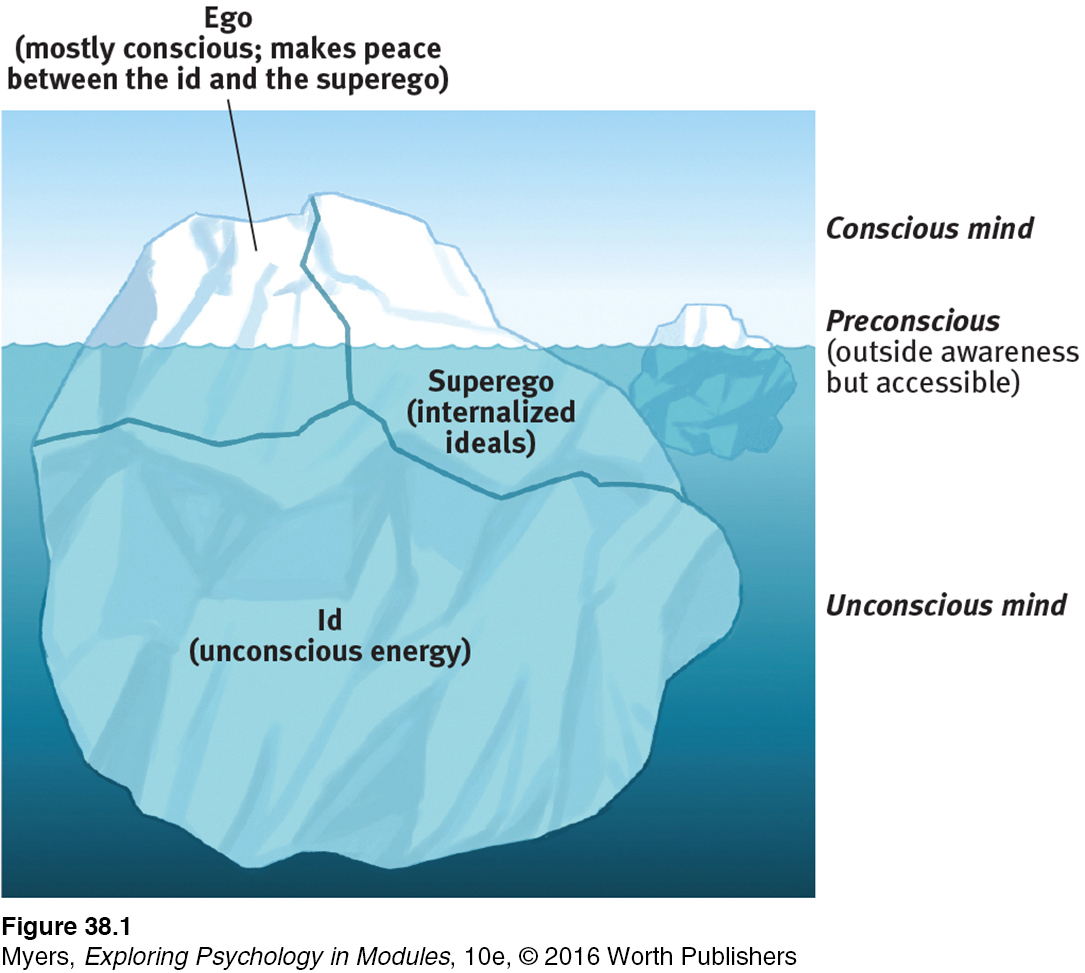

Basic to Freud’s theory was his belief that the mind is mostly hidden (FIGURE 38.1). Our conscious awareness is like the part of an iceberg that floats above the surface. Beneath our awareness is the larger unconscious mind, with its thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. Some of these thoughts we store temporarily in a preconscious area, from which we can retrieve them into conscious awareness. Of greater interest to Freud was the mass of unacceptable passions and thoughts that he believed we repress, or forcibly block from our consciousness because they would be too unsettling to acknowledge. Freud believed that without our awareness, these troublesome feelings and ideas powerfully influence us. Such feelings, he said, sometimes surface in disguised forms—

PERSONALITY STRUCTURE

38-

In Freud’s view, human personality—

id a reservoir of unconscious psychic energy that, according to Freud, strives to satisfy basic sexual and aggressive drives. The id operates on the pleasure principle, demanding immediate gratification.

The id’s unconscious psychic energy constantly strives to satisfy basic drives to survive, reproduce, and aggress. The id operates on the pleasure principle: It seeks immediate gratification. To envision an id-

ego the largely conscious, “executive” part of personality that, according to Freud, mediates among the demands of the id, superego, and reality. The ego operates on the reality principle, satisfying the id’s desires in ways that will realistically bring pleasure rather than pain.

As the ego develops, the young child responds to the real world. The ego, operating on the reality principle, seeks to gratify the id’s impulses in realistic ways that will bring long-

superego the part of personality that, according to Freud, represents internalized ideals and provides standards for judgment (the conscience) and for future aspirations.

Around age 4 or 5, Freud theorized, a child’s ego recognizes the demands of the newly emerging superego, the voice of our moral compass (conscience) that forces the ego to consider not only the real but the ideal. The superego focuses on how we ought to behave. It strives for perfection, judging actions and producing positive feelings of pride or negative feelings of guilt. Someone with an exceptionally strong superego may be virtuous yet guilt ridden; another with a weak superego may be outrageously self-

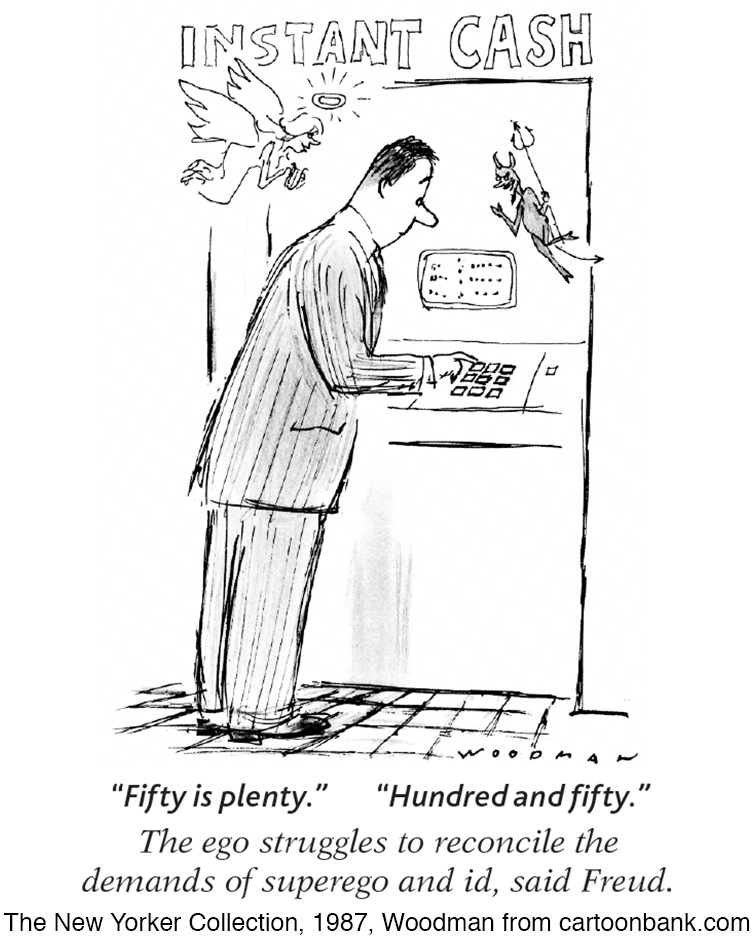

Because the superego’s demands often oppose the id’s, the ego struggles to reconcile the two. The ego is the personality “executive,” mediating among the impulsive demands of the id, the restraining demands of the superego, and the real-

PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

38-

psychosexual stages the childhood stages of development (oral, anal, phallic, latency, genital) during which, according to Freud, the id’s pleasure-

Analysis of his patients’ histories convinced Freud that personality forms during life’s first few years. He concluded that children pass through a series of psychosexual stages, during which the id’s pleasure-

Oedipus [ED-

Freud believed that during the phallic stage, for example, boys develop both unconscious sexual desires for their mother and jealousy and hatred for their father, whom they consider a rival. Given these feelings, he thought, boys also experience guilt and a lurking fear of punishment, perhaps by castration, from their father. Freud called this collection of feelings the Oedipus complex after the Greek legend of Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. Some psychoanalysts in Freud’s era believed that girls experienced a parallel Electra complex.

identification the process by which, according to Freud, children incorporate their parents’ values into their developing superegos.

Children eventually cope with the threatening feelings, said Freud, by repressing them and by trying to become like the rival parent. It’s as though something inside the child decides, “If you can’t beat ’em [the same-

fixation according to Freud, a lingering focus of pleasure-

In Freud’s view, conflicts unresolved during earlier psychosexual stages could surface as maladaptive behavior in the adult years. At any point in the oral, anal, or phallic stages, strong conflict could lock, or fixate, the person’s pleasure-

Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

| Stage | Focus |

| Oral (0- |

Pleasure centers on the mouth— |

| Anal (18– |

Pleasure focuses on bowel and bladder elimination; coping with demands for control |

| Phallic (3– |

Pleasure zone is the genitals; coping with incestuous sexual feelings |

| Latency (6 to puberty) | A phase of dormant sexual feelings |

| Genital (puberty on) | Maturation of sexual interests |

Freud’s ideas of sexuality were controversial in his own time. “Freud was called a dirty-

DEFENSE MECHANISMS

38-

Anxiety, said Freud, is the price we pay for civilization. As members of social groups, we must control our sexual and aggressive impulses, not act them out. But sometimes the ego fears losing control of this inner id-

defense mechanisms in psychoanalytic theory, the ego’s protective methods of reducing anxiety by unconsciously distorting reality.

repression in psychoanalytic theory, the basic defense mechanism that banishes from consciousness anxiety-

Freud proposed that the ego protects itself with defense mechanisms—tactics that reduce or redirect anxiety by distorting reality. For Freud, all defense mechanisms function indirectly and unconsciously. Just as the body unconsciously defends itself against disease, so also does the ego unconsciously defend itself against anxiety. For example, repression banishes anxiety-

Freud believed he could glimpse the unconscious seeping through when a financially stressed patient, not wanting any large pills, said, “Please do not give me any bills, because I cannot swallow them.” Freud also viewed jokes as expressions of repressed sexual and aggressive tendencies, and dreams as the “royal road to the unconscious.” The remembered content of dreams (their manifest content) he believed to be a censored expression of the dreamer’s unconscious wishes (the dream’s latent content). In his dream analyses, Freud searched for patients’ inner conflicts.

TABLE 38.2 describes a sampling of six other well-

Six Defense Mechanisms Freud believed that repression, the basic mechanism that banishes anxiety-

| Defense Mechanism | Unconscious Process Employed to Avoid Anxiety- |

Example |

| Regression | Retreating to a more infantile psychosexual stage, where some psychic energy remains fixated. | A little boy reverts to the oral comfort of thumb sucking in the car on the way to his first day of school. |

| Reaction formation | Switching unacceptable impulses into their opposites. | Repressing angry feelings, a person displays exaggerated friendliness. |

| Projection | Disguising one’s own threatening impulses by attributing them to others. | “The thief thinks everyone else is a thief” (an El Salvadoran saying). |

| Rationalization | Offering self- |

A habitual drinker says she drinks with her friends “just to be sociable.” |

| Displacement | Shifting sexual or aggressive impulses toward a more acceptable or less threatening object or person. | A little girl kicks the family dog after her mother sends her to her room. |

| Denial | Refusing to believe or even perceive painful realities. | A partner denies evidence of his loved one’s affair. |

“I remember your name perfectly but I just can’t think of your face.”

Oxford professor W. A. Spooner (1844–

RETRIEVE IT

Question

According to Freud's ideas about the three-

Question

In the psychoanalytic view, conflicts unresolved during one of the psychosexual stages may lead to at that stage.

Question

Freud believed that our defense mechanisms operate (consciously/unconsciously) and defend us against .

The Neo-Freudian and Later Psychodynamic Theorists

38-

In a historical period when people never talked about sex, and certainly not conscious desires for sex with one’s parent, Freud’s writings prompted debate. “In the Middle Ages, they would have burned me,” observed Freud to a friend. “Now they are content with burning my books” (Jones, 1957). Despite the controversy, Freud attracted followers. Several young, ambitious physicians formed an inner circle around their strong-

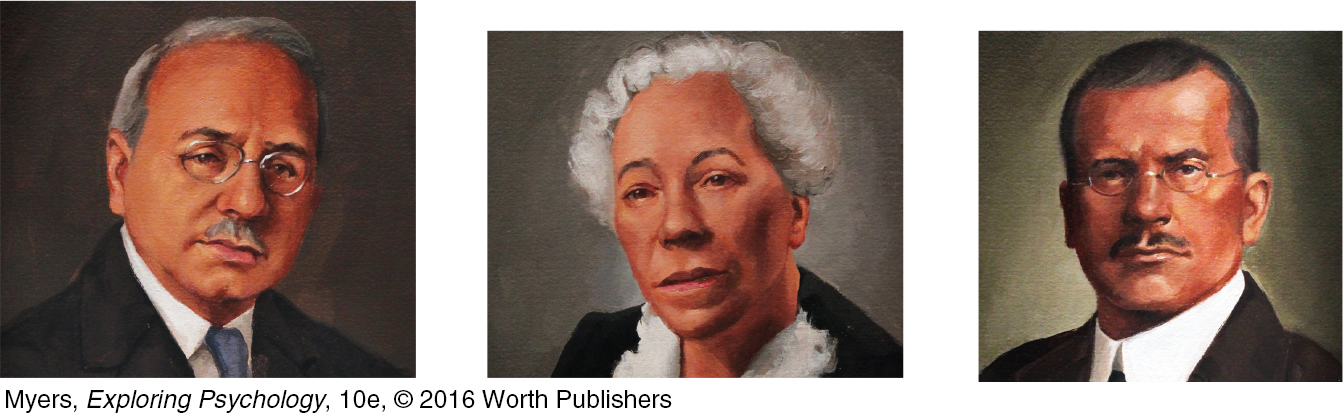

Alfred Adler and Karen Horney [HORN-

collective unconscious Carl Jung’s concept of a shared, inherited reservoir of memory traces from our species’ history.

Carl Jung [Yoong] started out a strong follower of Freud, but then veered off on his own. Jung placed less emphasis on social factors and agreed with Freud that the unconscious exerts a powerful influence. But to Jung, the unconscious contains more than our repressed thoughts and feelings. He believed we also have a collective unconscious, a common reservoir of images, or archetypes, derived from our species’ universal experiences. Jung said that the collective unconscious explains why, for many people, spiritual concerns are deeply rooted and why people in different cultures share certain myths and images. Most of today’s psychologists discount the idea of inherited experiences. But they do believe that our shared evolutionary history shaped some universal dispositions and that experience can leave epigenetic marks.

Freud died in 1939. Since then, some of his ideas have been incorporated into the diversity of perspectives that make up psychodynamic theory. “Most contemporary [psychodynamic] theorists and therapists are not wedded to the idea that sex is the basis of personality,” noted Drew Westen (1996). They “do not talk about ids and egos, and do not go around classifying their patients as oral, anal, or phallic characters.” What they do assume, with Freud and with much support from today’s psychological science, is that much of our mental life is unconscious. With Freud, they also assume that we often struggle with inner conflicts among our wishes, fears, and values, and that childhood shapes our personality and ways of becoming attached to others.

For a helpful, 9-

For a helpful, 9-

Assessing Unconscious Processes

38-

Personality tests reflect the basic ideas of particular personality theories. So, what might be the assessment tool of choice for someone working in the Freudian tradition?

Such a test would need to provide some sort of road into the unconscious—

projective test a personality test, such as the Rorschach, that provides ambiguous stimuli designed to trigger projection of one’s inner dynamics.

Projective tests aim to provide this “psychological X-

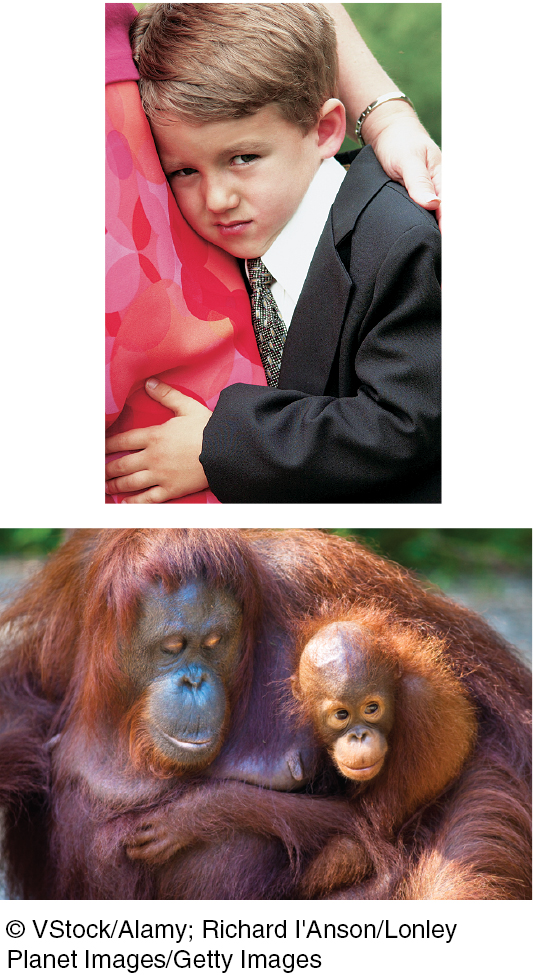

Henry Murray (1933) demonstrated a possible basis for such a test at a party hosted by his 11-

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) a projective test in which people express their inner feelings and interests through the stories they make up about ambiguous scenes.

A few years later, Murray introduced the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)—a test in which people view ambiguous pictures then make up stories about them. One use of such storytelling has been to assess achievement motivation (Schultheiss et al., 2014). Shown a daydreaming boy, those who imagine he is fantasizing about an achievement are presumed to be projecting their own goals. “As a rule,” said Murray, “the subject leaves the test happily unaware that he has presented the psychologist with what amounts to an X-

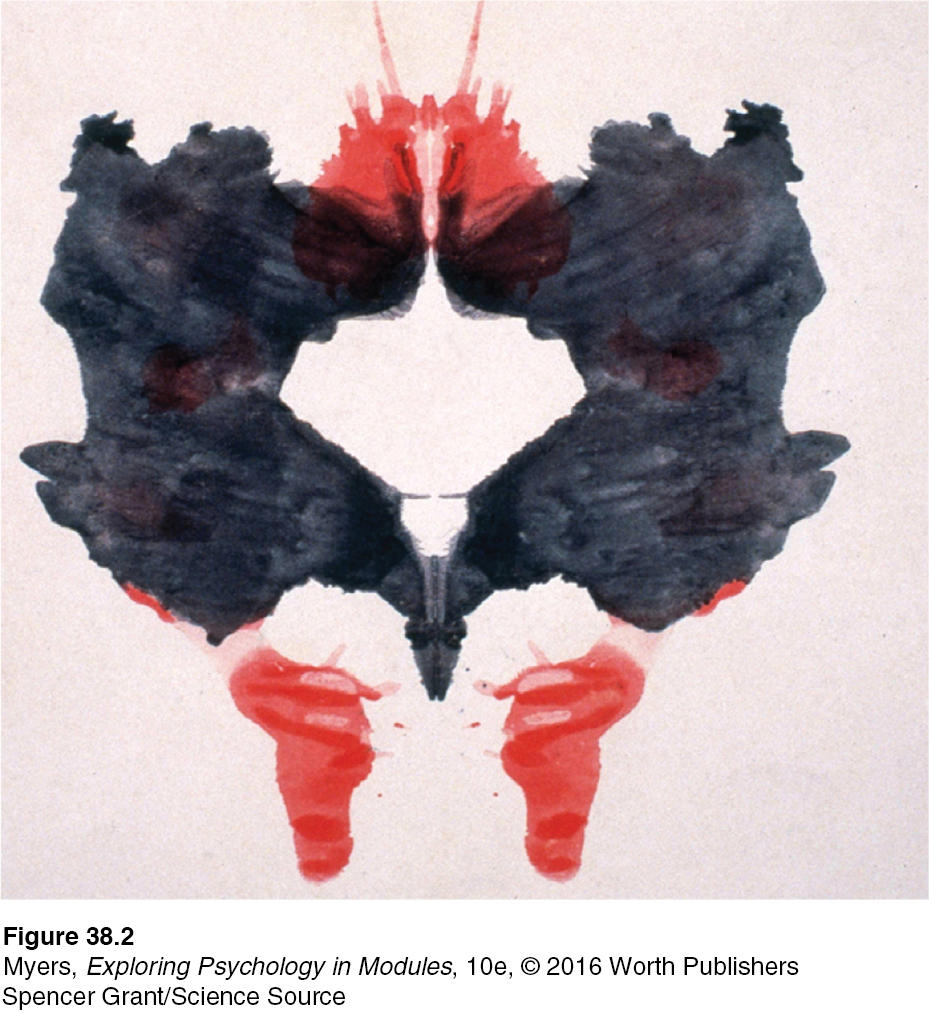

Rorschach inkblot test the most widely used projective test, a set of 10 inkblots, designed by Hermann Rorschach; seeks to identify people’s inner feelings by analyzing their interpretations of the blots.

The most widely used projective test left some blots on the name of Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach [ROAR-

“We don’t see things as they are; we see things as we are.”

The Talmud

Some clinicians cherish the Rorschach, even offering Rorschach-

Critics of the Rorschach insist the test is no emotional MRI. They argue that only a few of the many Rorschach-

“The Rorschach [Inkblot Test] has the dubious distinction of being, simultaneously, the most cherished and the most reviled of all psychological assessment tools.”

John Hunsley and J. Michael Bailey, 1999

Evaluating Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective and Modern Views of the Unconscious

38-

MODERN RESEARCH CONTRADICTS MANY OF FREUD’S IDEAS We critique Freud from a twenty-

“Many aspects of Freudian theory are indeed out of date, and they should be: Freud died in 1939, and he has been slow to undertake further revisions.”

Psychologist Drew Westen (1998)

But both Freud’s devotees and detractors agree that recent research contradicts many of his specific ideas. Today’s developmental psychologists see our development as lifelong, not fixed in childhood. They doubt that infants’ neural networks are mature enough to sustain as much emotional trauma as Freud assumed. Some think Freud overestimated parental influence and underestimated peer influence. They also doubt that conscience and gender identity form as the child resolves the Oedipus complex at age 5 or 6. We gain our gender identity earlier, and those who become strongly masculine or feminine do so even without a same-

Modern dream research disputes Freud’s belief that dreams disguise and fulfill wishes. And slips of the tongue can be explained as competition between similar verbal choices in our memory network. Someone who says “I don’t want to do that—

Psychologists also criticize Freud’s theory for its scientific shortcomings. It’s important to remember that good scientific theories explain observations and offer testable hypotheses. Freud’s theory rests on few objective observations, and parts of it offer few testable hypotheses. For Freud, his own recollections and interpretations of patients’ free associations, dreams, and slips were evidence enough.

What is the most serious problem with Freud’s theory? It offers after-

So, should psychology post an “Allow Natural Death” order on this old theory? Freud’s supporters object. To criticize Freudian theory for not making testable predictions is, they say, like criticizing baseball for not being an aerobic exercise, something it was never intended to be. Freud never claimed that psychoanalysis was predictive science. He merely claimed that, looking back, psychoanalysts could find meaning in our state of mind (Rieff, 1979).

“We are arguing like a man who should say, ‘If there were an invisible cat in that chair, the chair would look empty; but the chair does look empty; therefore there is an invisible cat in it’.”

C. S. Lewis, Four Loves, 1958

Freud’s supporters also note that some of his ideas are enduring. It was Freud who drew our attention to the unconscious and the irrational, at a time when such ideas were not popular. Today many researchers study our irrationality (Ariely, 2010). Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for his studies of our faulty decision making. Freud also drew our attention to the importance of human sexuality, and to the tension between our biological impulses and our social well-

“Although [Freud] clearly made a number of mistakes in the formulation of his ideas, his understanding of unconscious mental processes was pretty much on target. In fact, it is very consistent with modern neuroscientists’ belief that most mental processes are unconscious.”

Nobel Prize–

MODERN RESEARCH CHALLENGES THE IDEA OF REPRESSION

Psychoanalytic theory presumes that we often repress offending wishes, banishing them into the unconscious until they resurface, like long-

Today’s researchers agree that we sometimes spare our egos by neglecting threatening information (Green et al., 2008). Yet many contend that repression, if it ever occurs, is a rare mental response to terrible trauma. Even those who witnessed a parent’s murder or survived Nazi death camps have retained their unrepressed memories of the horror (Helmreich, 1992, 1994; Malmquist, 1986; Pennebaker, 1990). “Dozens of formal studies have yielded not a single convincing case of repression in the entire literature on trauma,” concluded personality researcher John Kihlstrom (2006).

“The overall findings . . . seriously challenge the classical psychoanalytic notion of repression.”

Psychologist Yacov Rofé, “Does Repression Exist?” 2008

Some researchers do believe that extreme, prolonged stress, such as the stress some severely abused children experience, might disrupt memory by damaging the hippocampus, which is important for processing conscious memories (Schacter, 1996). But the far more common reality is that high stress and associated stress hormones enhance memory. Indeed, rape, torture, and other traumatic events haunt survivors, who experience unwanted flashbacks. They are seared onto the soul. “You see the babies,” said Holocaust survivor Sally H. (1979). “You see the screaming mothers. You see hanging people. You sit and you see that face there. It’s something you don’t forget.”

“During the Holocaust, many children . . . were forced to endure the unendurable. For those who continue to suffer [the] pain is still present, many years later, as real as it was on the day it occurred.”

Eric Zillmer, Molly Harrower, Barry Ritzler, and Robert Archer, The Quest for the Nazi Personality, 1995

THE MODERN UNCONSCIOUS MIND

38-

Freud was right about a big idea that underlies today’s psychodynamic thinking: We indeed have limited access to all that goes on in our minds (Erdelyi, 1985, 1988, 2006; Norman, 2010). Our two-

Yet many research psychologists now think of the unconscious not as seething passions and repressive censoring but as cooler information processing that occurs without our awareness. To these researchers, the unconscious also involves

the schemas that automatically control our perceptions and interpretations.

the priming by stimuli to which we have not consciously attended.

the right-

hemisphere activity that enables the split- brain patient’s left hand to carry out an instruction the patient cannot verbalize.the implicit memories that operate without conscious recall, even among those with amnesia.

the emotions that activate instantly, before conscious analysis.

the stereotypes that automatically and unconsciously influence how we process information about others.

More than we realize, we fly on autopilot. Our lives are guided by off-

Research also supports two of Freud’s defense mechanisms. One study demonstrated reaction formation (trading unacceptable impulses for their opposite) in men who reported strong anti-

Freud’s projection (attributing our own threatening impulses to others) has also been confirmed. People do tend to see their traits, attitudes, and goals in others (Baumeister et al., 1998; Maner et al., 2005). Today’s researchers call this the false consensus effect—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are three big ideas that have survived from Freud's work in psychoanalytic theory? What are three ways in which Freud's work has been criticized?

Question

Which elements of traditional psychoanalysis have modern-