43.2 Other Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

43-

dissociative disorders controversial, rare disorders in which conscious awareness becomes separated (dissociated) from previous memories, thoughts, and feelings.

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders, in which a person’s conscious awareness dissociates (separates) from painful memories, thoughts, and feelings. The result may be a fugue state, a sudden loss of memory or change in identity, often in response to an overwhelmingly stressful situation. Such was the case for one Vietnam veteran who was haunted by his comrades’ deaths, and who had left his World Trade Center office shortly before the 9/11 attack. Later, he disappeared. Six months later, when he was discovered in a Chicago homeless shelter, he reported no memory of his identity or family (Stone, 2006).

dissociative identity disorder (DID) a rare dissociative disorder in which a person exhibits two or more distinct and alternating personalities. Formerly called multiple personality disorder.

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a fleeting sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. A massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which two or more distinct identities—

People diagnosed with DID (formerly called multiple personality disorder) are rarely violent. But cases have been reported of dissociations into a “good” and a “bad” (or aggressive) personality—

Speaking as Steve, Bianchi stated that he hated Ken because Ken was nice and that he (Steve), aided by a cousin, had murdered women. He also claimed Ken knew nothing about Steve’s existence and was innocent of the murders. Was Bianchi’s second personality a trick, simply a way of disavowing responsibility for his actions? Indeed, Bianchi—

UNDERSTANDING DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER Skeptics have raised serious concerns about DID. First, they find it suspicious that the disorder has such a short and localized history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses averaged 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995a). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—

Second, note the skeptics, DID varies by culture. It is much less prevalent outside North America. In Britain, DID—

Third, skeptics have asked, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Nicholas Spanos (1986, 1994, 1996) asked college students to pretend they were accused murderers being examined by a psychiatrist. Given the same hypnotic treatment Bianchi received, most spontaneously expressed a second personality. This discovery made Spanos wonder: Are dissociative identities simply a more extreme version of the varied “selves” we normally present—

“Pretense may become reality.”

Chinese proverb

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They find support for this view in the distinct body and brain states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). People with DID exhibit heightened activity in brain areas linked with the control and inhibition of traumatic memories (Elzinga et al., 2007). Abnormal brain anatomy can also accompany DID. Brain scans show shrinkage in areas that aid memory and detection of threat (Vermetten et al., 2006).

“Though this be madness, yet there is method in ’t.”

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1600

Both the psychodynamic and learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality could allow the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder. In this view, DID is a natural, protective response to traumatic experiences during childhood (Putnam, 1995; Spiegel, 2008). Many DID patients recall being physically, sexually, or emotionally abused as children (Gleaves, 1996; Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In one study of 12 murderers diagnosed with DID, 11 had suffered severe abuse, even torture, in childhood (Lewis et al., 1997). One had been set afire by his parents. Another had been used in child pornography and was scarred from being made to sit on a stove burner. Some critics wonder, however, whether vivid imagination or therapist suggestion contributed to such recollections (Kihlstrom, 2005).

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are skeptics who think DID is constructed out of the therapist-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The psychodynamic and learning perspectives agree that dissociative identity disorder symptoms are ways of dealing with anxiety. How do their explanations differ?

Personality Disorders

43-

personality disorders inflexible and enduring behavior patterns that impair social functioning.

The disruptive, inflexible, and enduring behavior patterns of personality disorders interfere with social functioning. These disorders tend to form three clusters, characterized by

anxiety, such as a fearful sensitivity to rejection that predisposes the withdrawn avoidant personality disorder.

eccentric or odd behaviors, such as the emotionless disengagement of schizotypal personality disorder.

dramatic or impulsive behaviors, such as the attention-

getting borderline personality disorder, the self- focused and self- inflating narcissistic personality disorder, and— what we next discuss as an in- depth example— the callous, and sometimes dangerous, antisocial personality disorder.

antisocial personality disorder a personality disorder in which a person (usually a man) exhibits a lack of conscience for wrongdoing, even toward friends and family members; may be aggressive and ruthless or a clever con artist.

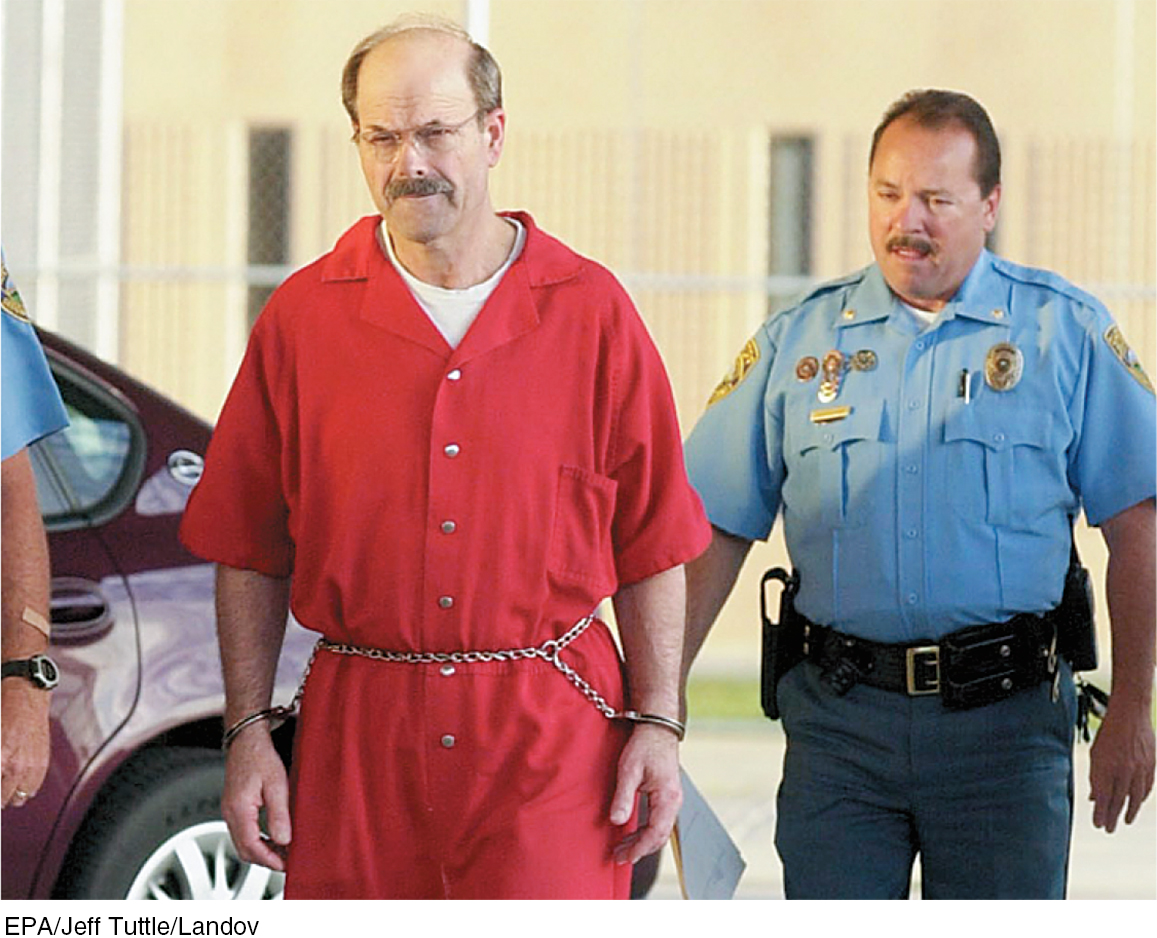

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER A person with antisocial personality disorder is typically a male whose lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as he begins to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). About half of such children become antisocial adults—

Antisocial personalities behave impulsively, and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Their impulsivity can have violent, horrifying consequences (Camp et al., 2013). Consider the case of Henry Lee Lucas. He killed his first victim when he was 13. He felt little regret then or later. He confessed that, during his 32 years of crime, he had brutally beaten, suffocated, stabbed, shot, or mutilated some 360 women, men, and children. For the last six years of his reign of terror, Lucas teamed with Ottis Elwood Toole, who reportedly slaughtered about 50 people he “didn’t think was worth living anyhow” (Darrach & Norris, 1984).

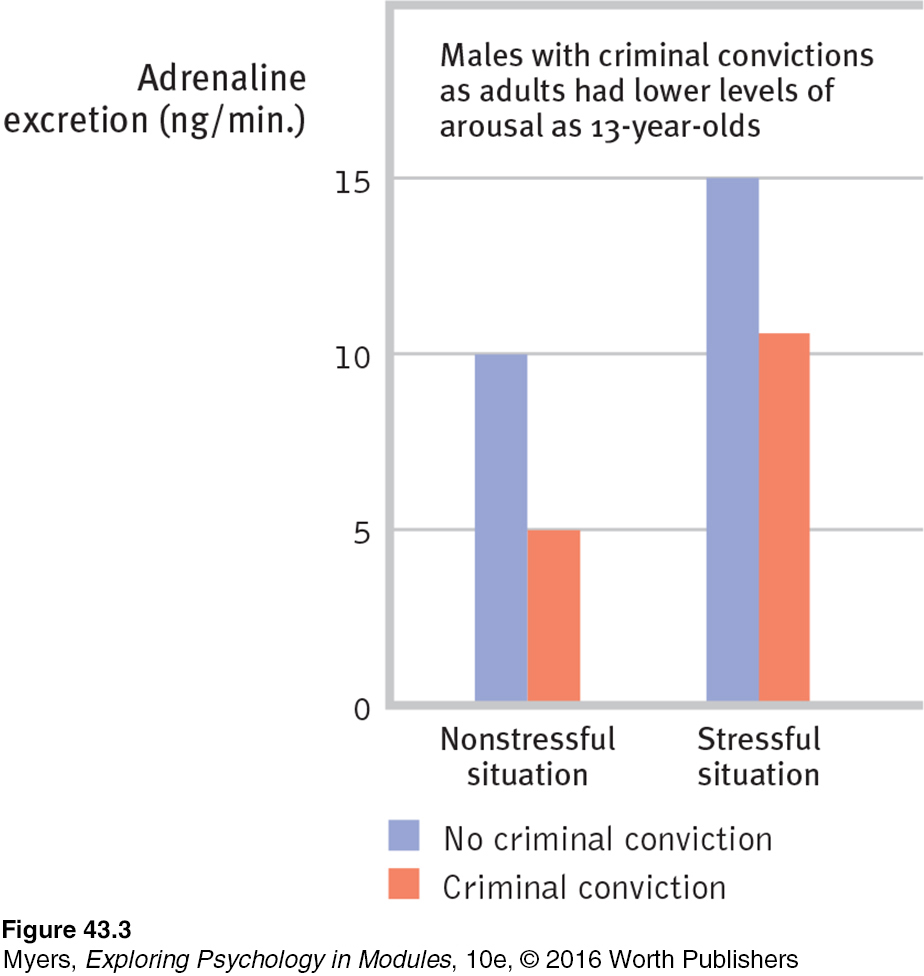

UNDERSTANDING ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Tuvblad et al., 2011). No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. Molecular geneticists have, however, identified some specific genes that are more common in those with antisocial personality disorder (Gunter et al., 2010). There may be a genetic predisposition toward a fearless and uninhibited life. The genes that put people at risk for antisocial behavior also increase the risk for substance use disorder, which helps explain why these disorders often appear in combination (Dick, 2007).

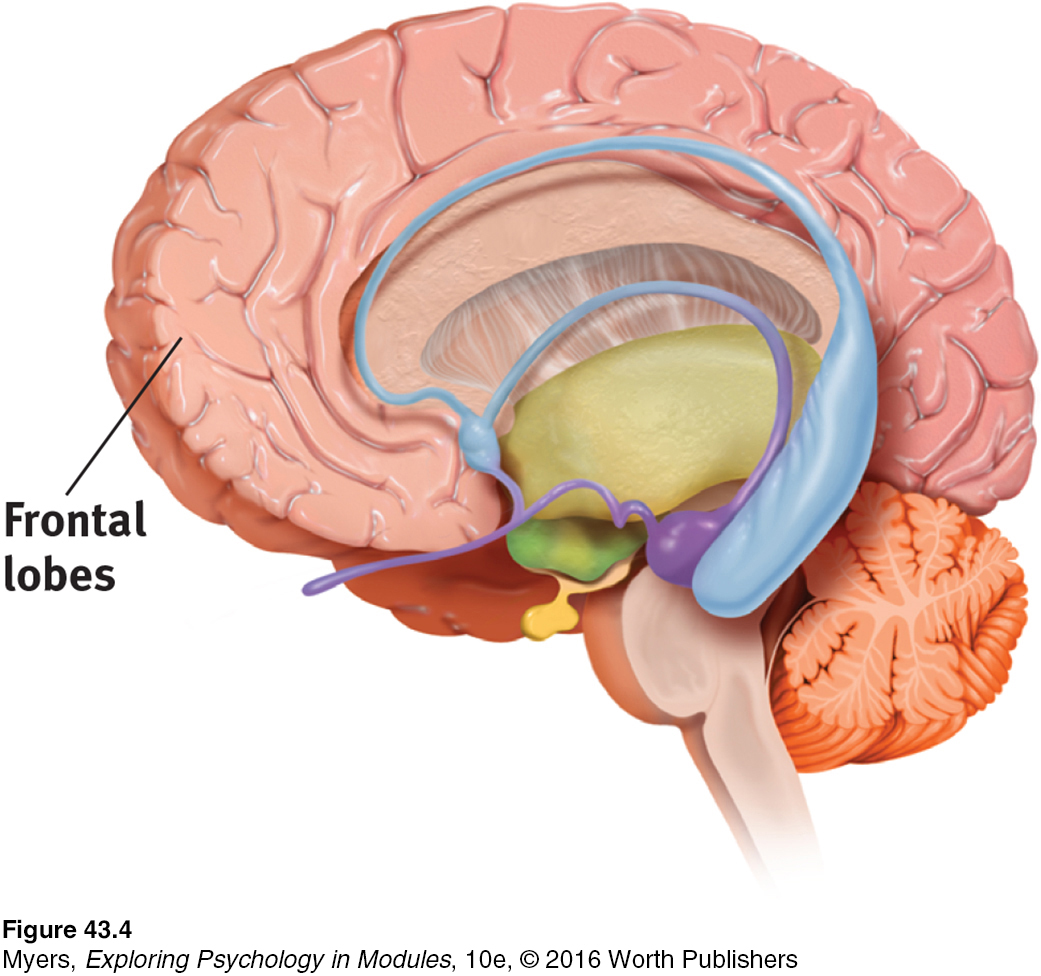

Genetic influences, often in combination with negative environmental factors such as childhood abuse, family instability, or poverty, help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). In people with antisocial criminal tendencies, the emotion-

Does a full Moon trigger “madness” in some people? James Rotton and I. W. Kelly (1985) examined data from 37 studies that related lunar phase to crime, homicides, crisis calls, and mental hospital admissions. Their conclusion: There is virtually no evidence of “Moon madness.” Nor does lunar phase correlate with suicides, assaults, emergency room visits, or traffic disasters (Martin et al., 1992; Raison et al., 1999).

Traits such as fearlessness and dominance can be adaptive. If channeled in more productive directions, fearlessness may lead to athletic stardom, adventurism, or courageous heroism (Poulton & Milne, 2002; Smith et al., 2013). One analysis of 42 American presidents showed that they scored higher than the general population on such traits as fearlessness and dominance (Lilienfeld et al., 2012). Lacking a sense of social responsibility, the same disposition may produce a cool con artist or killer (Lykken, 1995).

With antisocial behavior, as with so much else, nature and nurture interact and the biopsychosocial perspective helps us understand the whole story. To explore the neural basis of antisocial personality disorder, scientists are trying to identify brain activity differences in antisocial criminals. Shown emotionally evocative photographs, such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat, criminals with antisocial personality disorder display blunted heart rate and perspiration responses, and less activity in brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). They also have a larger and hyper-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How do biological and psychological factors contribute to antisocial personality disorder?

Eating Disorders

43-

Our bodies are naturally disposed to maintain a steady weight, including stored energy reserves for times when food becomes unavailable. But sometimes psychological influences overwhelm biological wisdom. This becomes painfully clear in three eating disorders:

anorexia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person (usually an adolescent female) maintains a starvation diet despite being significantly underweight; sometimes accompanied by excessive exercise.

bulimia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person alternates binge eating (usually of high-

binge-eating disorder significant binge-

Anorexia nervosa typically begins as a weight-

loss diet. People with anorexia— usually adolescents and 9 out of 10 times females— drop significantly below normal weight. Yet they feel fat, fear being fat, diet obsessively, and sometimes exercise excessively. About half of those with anorexia display a binge- purge- depression cycle. Bulimia nervosa, unlike anorexia, is marked by weight fluctuations within or above normal ranges. This makes the condition easy to hide. Bulimia may also be triggered by a weight-

loss diet, broken by gorging on forbidden foods. In a cycle of repeating episodes, people with this disorder— mostly women in their late teens or early twenties— alternate binge eating and purging (through vomiting or laxative use) (Wonderlich et al., 2007). Fasting or excessive exercise may follow. Preoccupied with food (craving sweets and high- fat foods), and fearful of becoming overweight, binge- purge eaters experience bouts of depression, guilt, and anxiety during and following binges (Hinz & Williamson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2002). Those with binge-eating disorder engage in significant bouts of overeating, followed by remorse. But they do not purge, fast, or exercise excessively, and thus may be overweight.

A U.S. National Institute of Mental Health-

UNDERSTANDING EATING DISORDERS Eating disorders are not (as some have speculated) a telltale sign of childhood sexual abuse (Smolak & Murnen, 2002; Stice, 2002). The family environment may influence eating disorders in other ways, however. For example, anorexia patients’ families tend to be competitive, high achieving, and protective (Berg et al., 2014; Pate et al., 1992; Yates, 1989, 1990). Those with eating disorders often have low self-

Heredity also matters. Identical twins share these disorders more often than fraternal twins do (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2009; Root et al., 2010). Scientists are now searching for culprit genes, which may influence the body’s available serotonin and estrogen (Klump & Culbert, 2007). Data from 15 studies indicate that having a gene that reduces available serotonin adds 30 percent to a person’s risk of anorexia or bulimia (Calati et al., 2011).

But eating disorders also have cultural and gender components. Ideal shapes vary across culture and time. In impoverished countries—

Those most vulnerable to eating disorders are also those (usually women or gay men) who most idealize thinness and have the greatest body dissatisfaction (Feldman & Meyer, 2010; Kane, 2010; Stice et al., 2010). Should it surprise us, then, that when women view real and doctored images of unnaturally thin models and celebrities, they often feel ashamed, depressed, and dissatisfied with their own bodies—

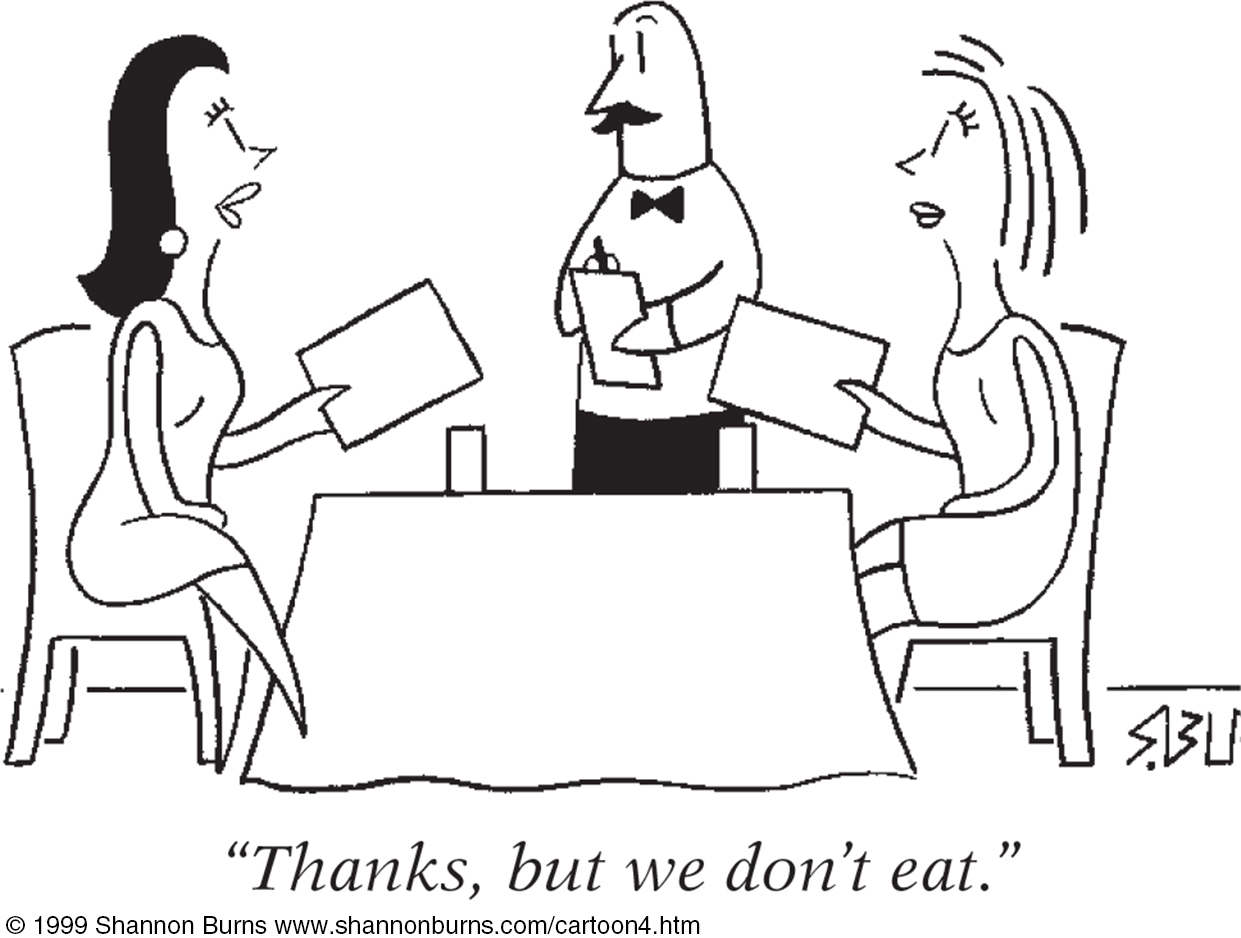

“Why do women have such low self-

Dave Barry, 1999

There is, however, more to body dissatisfaction and anorexia than media effects (Ferguson et al., 2011). Peer influences, such as teasing, also matter. Nevertheless, the sickness of today’s eating disorders stems in part from today’s weight-

If cultural learning contributes to eating behavior, then might prevention programs increase acceptance of one’s body? Reviews of prevention studies answer Yes. They seem especially effective if the programs are interactive and focused on girls over age 15 (Beintner et al., 2012; Stice et al., 2007; Vocks et al., 2010).

* * *

The bewilderment, fear, and sorrow caused by psychological disorders are real. But as our next topic—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

People with (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) continue to want to lose weight even when they are underweight. Those with (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) tend to have weight that fluctuates within or above normal ranges.