44.2 Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Therapies

44-

psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud’s therapeutic technique. Freud believed the patient’s free associations, resistances, dreams, and transferences—

The first major psychological therapy was Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Although few clinicians today practice therapy as Freud did, his work deserves discussion. It helped form the foundation for treating psychological disorders, and it continues to influence modern therapists working from the psychodynamic perspective.

The Goals of Psychoanalysis

Freud believed that in therapy, people could achieve healthier, less anxious living by releasing the energy they had previously devoted to id-

Freud’s therapy aimed to bring patients’ repressed or disowned feelings into conscious awareness. By helping them reclaim their unconscious thoughts and feelings, and by giving them insight into the origins of their disorders, he aimed to help them reduce growth-

The Techniques of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis is historical reconstruction. Psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the power of childhood experiences to mold the adult. Thus, it aims to unearth the past in the hope of loosening its bonds on the present. After discarding hypnosis as an unreliable excavator, Freud turned to free association.

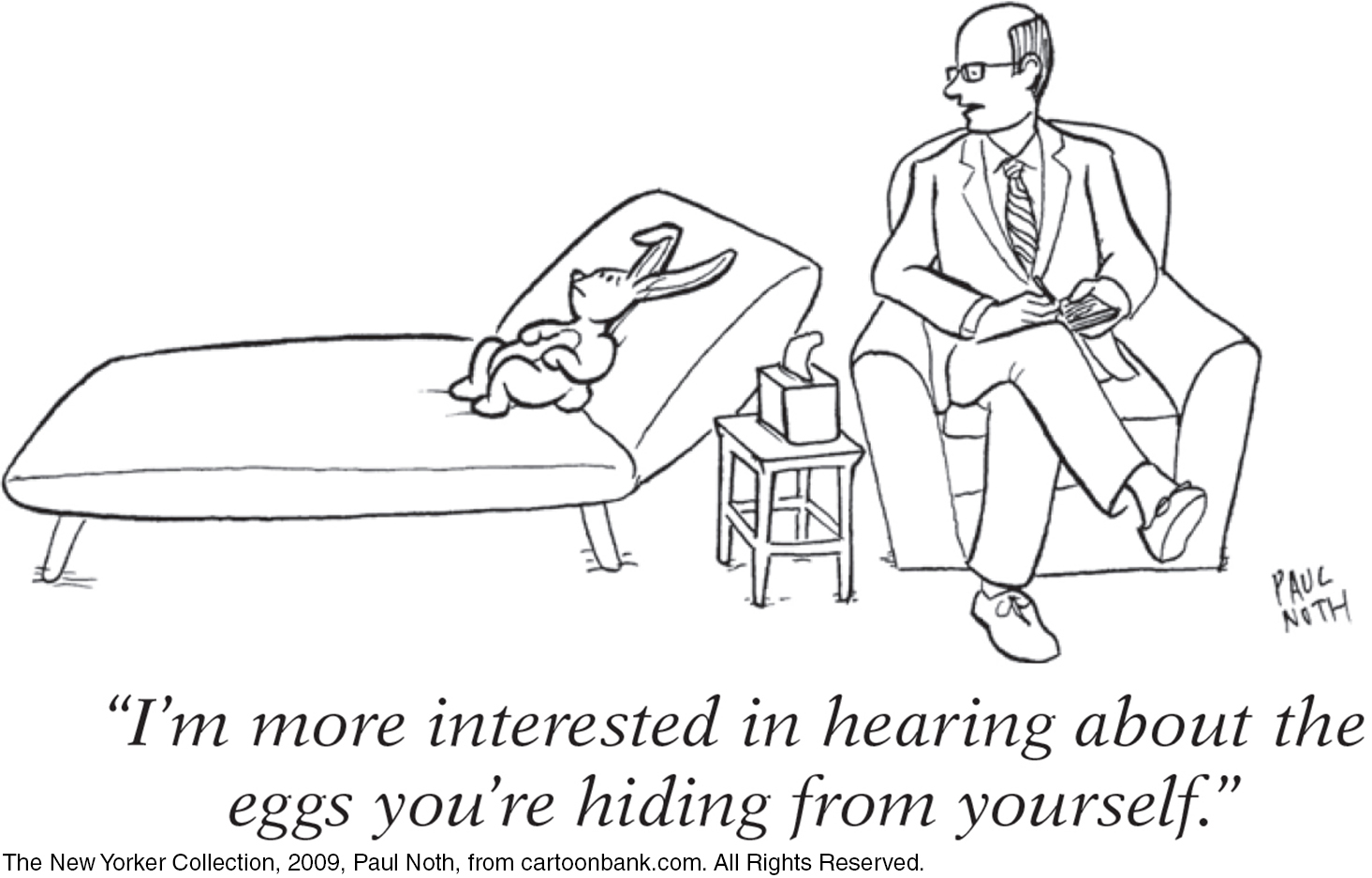

Imagine yourself as a patient using free association. You begin by relaxing, perhaps by lying on a couch. As the psychoanalyst sits out of your line of vision, you say aloud whatever comes to mind. At one moment, you’re relating a childhood memory. At another, you’re describing a dream or recent experience. It sounds easy, but soon you may notice how often you edit your thoughts as you speak. You pause for a second before uttering an embarrassing thought. You omit what seems trivial, irrelevant, or shameful. Sometimes your mind goes blank or you clutch up, unable to remember important details. You may joke or change the subject to something less threatening.

resistance in psychoanalysis, the blocking from consciousness of anxiety-

interpretation in psychoanalysis, the analyst’s noting supposed dream meanings, resistances, and other significant behaviors and events in order to promote insight.

To the analyst, these mental blocks indicate resistance. They hint that anxiety lurks and you are defending against sensitive material. The analyst will note your resistances and then provide insight into their meaning. If offered at the right moment, this interpretation—of, say, your not wanting to talk about your mother—

transference in psychoanalysis, the patient’s transfer to the analyst of emotions linked with other relationships (such as love or hatred for a parent).

Over many such sessions, your relationship patterns surface in your interactions with your therapist. You may find yourself experiencing strong positive or negative feelings for your analyst. The analyst may suggest you are transferring feelings, such as feelings of dependency or mingled love and anger, that you experienced in earlier relationships with family members or other important people. By exposing such feelings, you may gain insight into your current relationships.

Relatively few North American therapists now offer traditional psychoanalysis. Much of its underlying theory is not supported by scientific research. Analysts’ interpretations do not follow the scientific method—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

In psychoanalysis, when patients experience strong feelings for their therapist, this is called . Patients are said to demonstrate anxiety when they put up mental blocks around sensitive memories, indicating . The therapist will attempt to provide insight into the underlying anxiety by offering a(n) of the mental blocks.

“I haven’t seen my analyst in 200 years. He was a strict Freudian. If I’d been going all this time, I’d probably almost be cured by now.”

Woody Allen, after awakening from suspended animation in the movie Sleeper

Psychodynamic Therapy

psychodynamic therapy therapy deriving from the psychoanalytic tradition; views individuals as responding to unconscious forces and childhood experiences, and seeks to enhance self-

Although influenced by Freud’s ideas, psychodynamic therapists don’t talk much about id, ego, and superego. Instead, they try to help people understand their current symptoms by focusing on themes across important relationships, including childhood experiences and the therapist relationship. “We can have loving feelings and hateful feelings toward the same person,” notes psychodynamic therapist Jonathan Shedler (2009), and “we can desire something and also fear it.” Client-

Therapist David Shapiro (1999, p. 8) illustrates this method with the case of a young man who had told women that he loved them, when he knew that he didn’t. His explanation: They expected it, so he said it. But with his wife, who wished he would say that he loved her, he found he couldn’t do that—

Therapist: Do you mean, then, that if you could, you would like to?

Patient: Well, I don’t know…. Maybe I can’t say it because I’m not sure it’s true. Maybe I don’t love her.

Further interactions revealed that he could not express real love because it would feel “mushy” and “soft” and therefore unmanly. Shapiro noted that this young man was “in conflict with himself, and he [was] cut off from the nature of that conflict.” With such patients, who are estranged from themselves, therapists using psychodynamic techniques “are in a position to introduce them to themselves. We can restore their awareness of their own wishes and feelings, and their awareness, as well, of their reactions against those wishes and feelings.”

Exploring past relationship troubles may help clients understand the origin of their current difficulties. Jonathan Shedler (2010) recalled his patient “Jeffrey’s” complaints of difficulty getting along with his colleagues and wife, who saw him as hypercritical. Jeffrey then “began responding to me as if I were an unpredictable, angry adversary.” Shedler seized this opportunity to help Jeffrey recognize the relationship pattern, and its roots in the attacks and humiliation he experienced from his alcohol-