44.4 Behavior Therapies

44-

behavior therapy therapy that applies learning principles to the elimination of unwanted behaviors.

The insight therapies assume that self-

Classical Conditioning Techniques

One cluster of behavior therapies derives from principles developed in Ivan Pavlov’s conditioning experiments. As Pavlov and others showed, we learn various behaviors and emotions through classical conditioning. If we’re attacked by a dog, we may thereafter have a conditioned fear response when other dogs approach: Our fear generalizes and all dogs become conditioned stimuli.

Could maladaptive symptoms be examples of conditioned responses? If so, might reconditioning be a solution? Learning theorist O. H. Mowrer thought so. He developed a successful conditioning therapy for chronic bed-

counterconditioning behavior therapy procedures that use classical conditioning to evoke new responses to stimuli that are triggering unwanted behaviors; include exposure therapies and aversive conditioning.

Can we unlearn fear responses through new conditioning? Many people have. One example: The fear of riding in an elevator is often a learned fear response to being in a confined space. Counterconditioning pairs the trigger stimulus (in this case, the enclosed space of the elevator) with a new response (relaxation) that is incompatible with fear. Two specific counterconditioning techniques—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What might a psychodynamic therapist say about Mowrer's therapy for bed-

EXPOSURE THERAPIES Picture this scene: Behavioral psychologist Mary Cover Jones is working with 3-

exposure therapies behavioral techniques, such as systematic desensitization and virtual reality exposure therapy, that treat anxieties by exposing people (in imagination or actual situations) to the things they fear and avoid.

Unfortunately for many who might have been helped by Jones’ procedures, her story of Peter and the rabbit did not enter psychology’s lore when it was reported in 1924. It was more than 30 years before psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe (1958; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997) refined Jones’ counterconditioning technique into the exposure therapies used today. These therapies, in a variety of ways, try to change people’s reactions by repeatedly exposing them to stimuli that trigger unwanted reactions. With repeated exposure to what they normally avoid or escape, people adapt. We all experience this process in everyday life. A person moving to a new apartment may be annoyed by nearby loud traffic noise, but only for a while. With repeated exposure, the person adapts. So, too, with people who have fear reactions to specific events. Exposed repeatedly to the situation that once petrified them, they can learn to react less anxiously (Barrera et al., 2013; Foa et al., 2013).

systematic desensitization a type of exposure therapy that associates a pleasant, relaxed state with gradually increasing anxiety-

One form of exposure therapy widely used to treat phobias is systematic desensitization. You cannot simultaneously be anxious and relaxed. Therefore, if you can repeatedly relax when facing anxiety-

In the next step, the therapist would train you in progressive relaxation. You would learn to relax one muscle group after another, until you achieved a comfortable, complete relaxation. The therapist might then ask you to imagine, with your eyes closed, a mildly anxiety-

The therapist will then move to the next item on your list, again using relaxation techniques to desensitize you to each imagined situation. After several sessions, you will move to actual situations and practice what you had only imagined before. You will begin with relatively easy tasks and gradually move to more anxiety-

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address, 1933

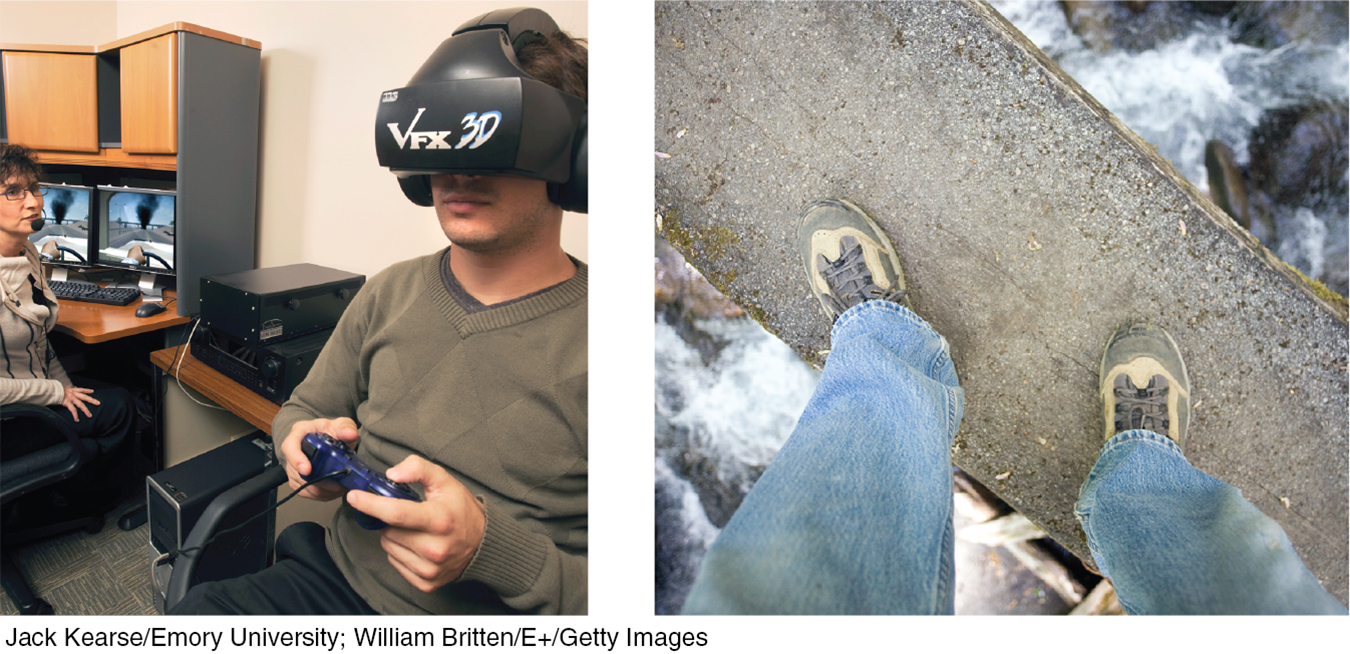

virtual reality exposure therapy an anxiety treatment that progressively exposes people to electronic simulations of their greatest fears, such as airplane flying, spiders, or public speaking.

If an anxiety-

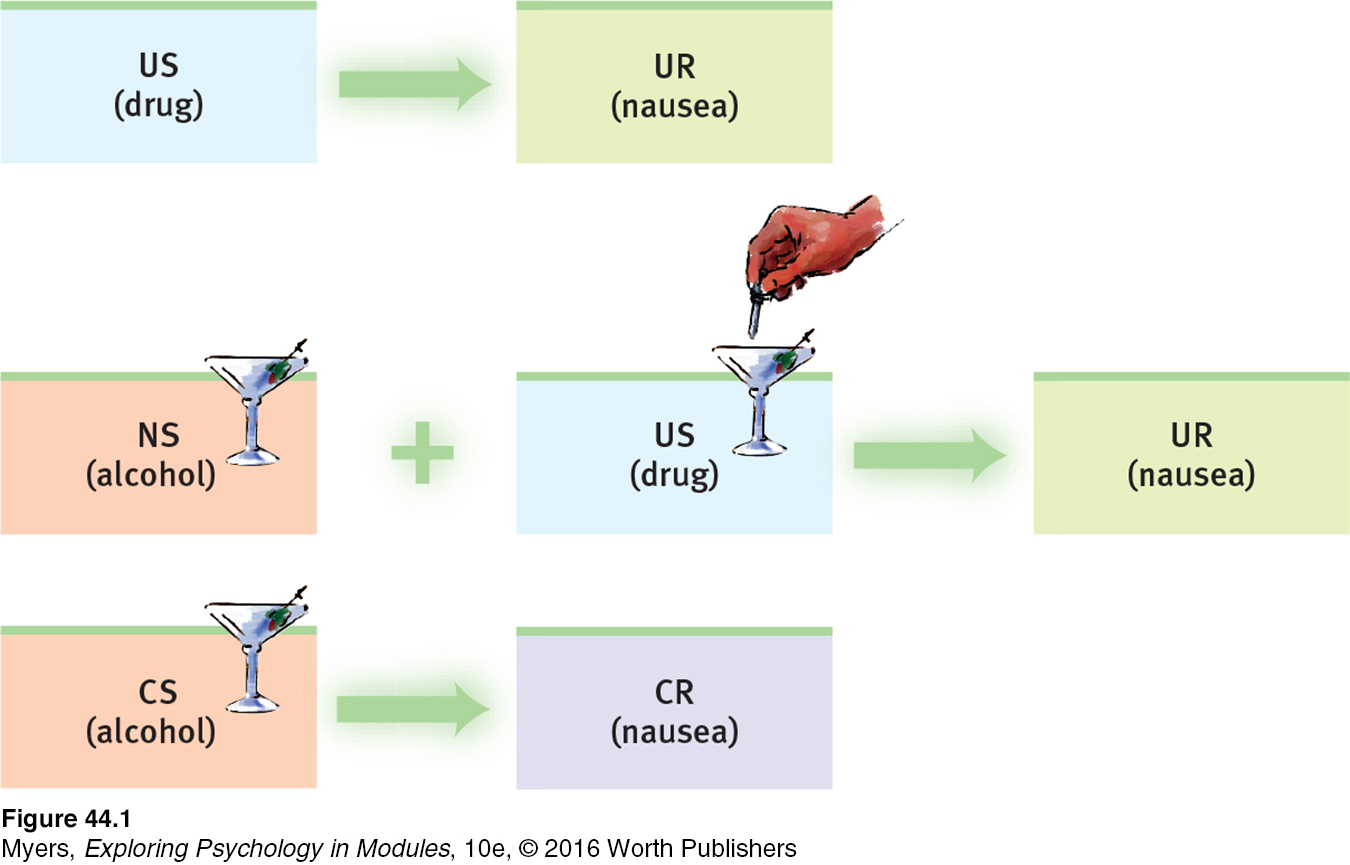

aversive conditioning a type of counterconditioning that associates an unpleasant state (such as nausea) with an unwanted behavior (such as drinking alcohol).

AVERSIVE CONDITIONING Exposure therapies enable a more relaxed, positive response to an upsetting harmless stimulus. Aversive conditioning creates a negative (aversive) response to a harmful stimulus (such as alcohol). Exposure therapies help you accept what you should do. Aversive conditioning helps you to learn what you should not do.

The aversive conditioning procedure is simple: It associates the unwanted behavior with unpleasant feelings. To treat nail biting, one can paint the fingernails with a nasty-

Does aversive conditioning work? In the short run it may. In one classic study, 685 hospital patients with alcohol use disorder completed an aversion therapy program (Wiens & Menustik, 1983). Over the next year, they returned for several booster treatments in which alcohol was paired with sickness. At the end of that year, 63 percent were still successfully abstaining. But after three years, only 33 percent had remained abstinent.

The problem is that in therapy (as in research), cognition influences conditioning. People know that outside the therapist’s office they can drink without fear of nausea. Their ability to discriminate between the aversive conditioning situation and all other situations can limit the treatment’s effectiveness. Thus, therapists often use aversive conditioning in combination with other treatments.

Operant Conditioning

44-

The work of B. F. Skinner and others teaches us a basic principle of operant conditioning: Voluntary behaviors are strongly influenced by their consequences. Knowing this, some behavior therapists practice behavior modification. They reinforce behaviors they consider desirable. And they fail to reinforce—

Using operant conditioning to solve specific behavior problems has raised hopes for some seemingly hopeless cases. Children with intellectual disabilities have been taught to care for themselves. Socially withdrawn children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have learned to interact. People with schizophrenia have been helped to behave more rationally in their hospital ward. In such cases, therapists used positive reinforcers to shape behavior. In a step-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Research Ethics below for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Research Ethics below for a helpful tutorial animation.

In extreme cases, treatment must be intensive. One study worked with 19 withdrawn, uncommunicative 3-

token economy an operant conditioning procedure in which people earn a token of some sort for exhibiting a desired behavior and can later exchange their tokens for various privileges or treats.

The rewards used to modify behavior vary because people differ in what they find reinforcing. For some, the reinforcing power of attention or praise is enough. Others require concrete rewards, such as food. In institutional settings, therapists may create a token economy. When people display desired behavior, such as getting out of bed, washing, dressing, eating, talking meaningfully, cleaning their rooms, or playing cooperatively, they receive a token or plastic coin. Later, they can exchange a number of these tokens for rewards, such as candy, TV time, day trips, or better living quarters. Token economies have been used successfully in various settings (homes, classrooms, hospitals, institutions for juvenile offenders) and among members of various populations (including disturbed children and people with schizophrenia and other mental disabilities).

Behavior modification critics express two concerns. The first is practical: How durable are the behaviors? Will people become so dependent on extrinsic rewards that the desired behaviors will stop when the reinforcers stop? Behavior modification advocates believe the behaviors will endure if therapists wean people from the tokens by shifting them toward other, real-

The second concern is ethical: Is it right for one human to control another’s behavior? Those who set up token economies deprive people of something they desire and decide which behaviors to reinforce. To critics, this whole process has an authoritarian taint. Advocates reply that control already exists; people’s destructive behavior patterns are already being maintained and perpetuated by natural reinforcers and punishers in their environments. Isn’t using positive rewards to reinforce adaptive behavior more humane than institutionalizing or punishing people? Advocates also argue that the right to effective treatment and an improved life justifies temporary deprivation.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are the insight therapies, and how do they differ from behavior therapies?

Question

Some maladaptive behaviors are learned. What hope does this fact provide?

Question

Exposure therapies and aversive conditioning are applications of conditioning. Token economies are an application of conditioning.