2.3 Psychology’s Research Ethics

2-

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

We have reflected on how a scientific approach can restrain biases. We have seen how case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys help us describe behavior. We have established how correlational studies assess the association between two factors, which indicates how well one thing predicts another. We have examined the logic that underlies experiments, which use control conditions and random assignment of participants to isolate the effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable.

Yet, even knowing this much, you may still be approaching psychology with a mixture of curiosity and apprehension. So before we plunge in, let’s entertain some common questions about psychology’s ethics and values.

Protecting Research Participants

STUDYING AND PROTECTING ANIMALS Many psychologists study nonhuman animals because they find them fascinating. They want to understand how different species learn, think, and behave. Psychologists also study animals to learn about people. We humans are not like animals; we are animals, sharing a common biology. Animal experiments have therefore led to treatments for human diseases—

“Rats are very similar to humans except that they are not stupid enough to purchase lottery tickets.”

Dave Barry, July 2, 2002

Humans are more complex, but the same processes by which we learn are present in rats, monkeys, and even sea slugs. The simplicity of the sea slug’s nervous system is precisely what makes it so revealing of the neural mechanisms of learning. Sharing such similarities, should we respect rather than experiment on our animal relatives? The animal protection movement protests the use of animals in psychological, biological, and medical research.

Out of this heated debate, two issues emerge. The basic one is whether it is right to place the well-

Second, if we do give human life first priority, what safeguards should protect the well-

Animals have themselves benefited from animal research. One Ohio team of research psychologists measured stress hormone levels in samples of millions of dogs brought each year to animal shelters. They devised handling and stroking methods to reduce stress and ease the dogs’ transition to adoptive homes (Tuber et al., 1999). Other studies have helped improve care and management in animals’ natural habitats. By revealing our behavioral kinship with animals and the remarkable intelligence of chimpanzees, gorillas, and other animals, experiments have also led to increased empathy and protection for them. At its best, a psychology concerned for humans and sensitive to animals serves the welfare of both.

“Please do not forget those of us who suffer from incurable diseases or disabilities who hope for a cure through research that requires the use of animals.”

Psychologist Dennis Feeney (1987)

“The greatness of a nation can be judged by the way its animals are treated.”

Mahatma Gandhi, 1869–

STUDYING AND PROTECTING HUMANS What about human participants? Does the image of white-

Occasionally, researchers do temporarily stress or deceive people, but only when they believe it is essential to a justifiable end, such as understanding and controlling violent behavior or studying mood swings. Some experiments won’t work if participants know everything beforehand. (Wanting to be helpful, the participants might try to confirm the researcher’s predictions.)

informed consent giving potential participants enough information about a study to enable them to choose whether they wish to participate.

debriefing the postexperimental explanation of a study, including its purpose and any deceptions, to its participants.

The ethics codes of the APA and the BPS urge researchers to (1) obtain human participants’ informed consent before the experiment, (2) protect participants from greater-

Values in Research

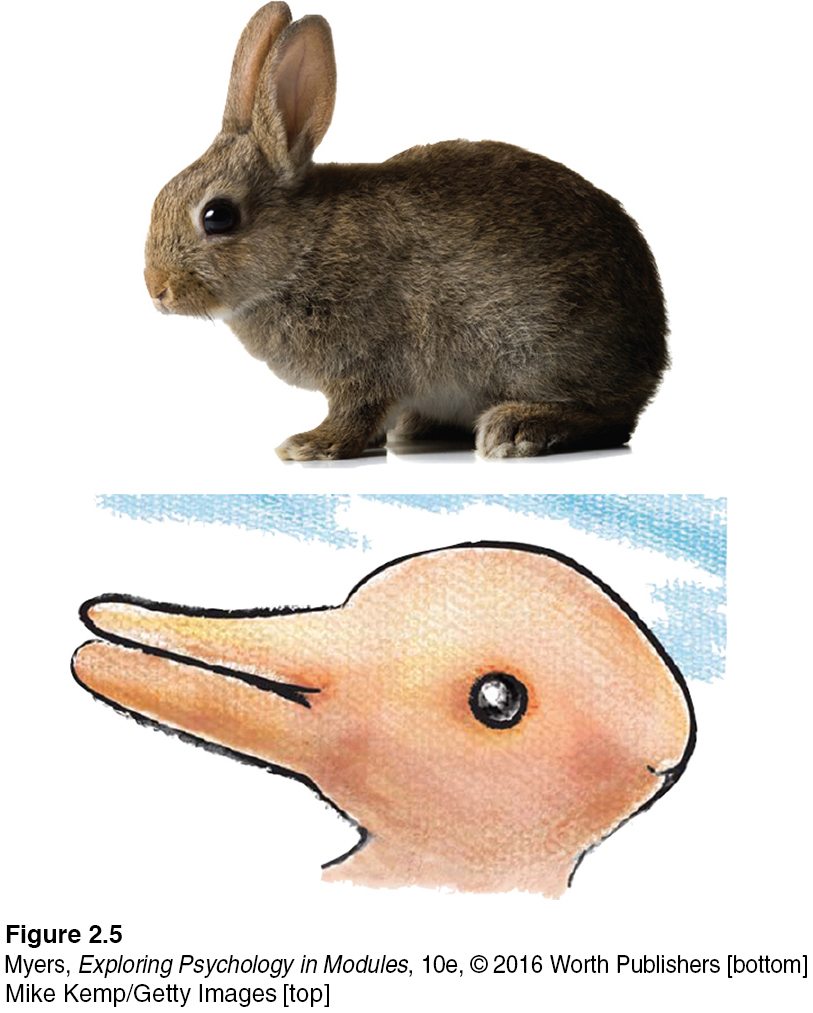

Values affect what we study, how we study it, and how we interpret results. Researchers’ values influence their choice of topics. Should we study worker productivity or worker morale? Sex discrimination or gender differences? Conformity or independence? Values can also color “the facts.” As we noted earlier, our preconceptions can bias our observations and interpretations; sometimes we see what we want or expect to see (FIGURE 2.5).

In psychology and in everyday speech, labels describe and labels evaluate: One person’s rigidity is another’s consistency. One person’s faith is another’s fanaticism. One country’s enhanced interrogation techniques become torture when practiced by its enemies. Our labeling someone as firm or stubborn, careful or picky, discreet or secretive reveals our own attitudes.

Popular applications of psychology also contain hidden values. If you defer to “professional” guidance about how to live—

Knowledge transforms us. Learning about the solar system and the germ theory of disease alters the way people think and act. Learning about psychology’s findings also changes people: They less often judge psychological disorders as moral failings, treatable by punishment and ostracism. They less often regard and treat women as men’s mental inferiors. They less often view and raise children as ignorant, willful beasts in need of taming. “In each case,” noted Morton Hunt (1990, p. 206), “knowledge has modified attitudes, and, through them, behavior.” Once aware of psychology’s well-

But bear in mind psychology’s limits. Don’t expect it to answer the ultimate questions, such as those posed by Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1904): “Why should I live? Why should I do anything? Is there in life any purpose which the inevitable death that awaits me does not undo and destroy?”

Although many of life’s significant questions are beyond psychology, some very important ones are illuminated by even a first psychology course. Through painstaking research, psychologists have gained insights into brain and mind, dreams and memories, depression and joy. Even the unanswered questions can renew our sense of mystery about “things too wonderful” for us yet to understand. Moreover, your study of psychology can help teach you how to ask and answer important questions—

If some people see psychology as merely common sense, others have a different concern—

Knowledge, like all power, can be used for good or evil. Nuclear power has been used to light up cities—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How are animal and human research participants protected?