1.1 The Scientific Attitude: Curious, Skeptical, and Humble

1-

To assist your active learning of psychology, numbered Learning Objectives, framed as questions, appear at the beginning of major sections. You can test your understanding by trying to answer the question before, and then again after, you read the section.

Underlying all science is, first, a hard-

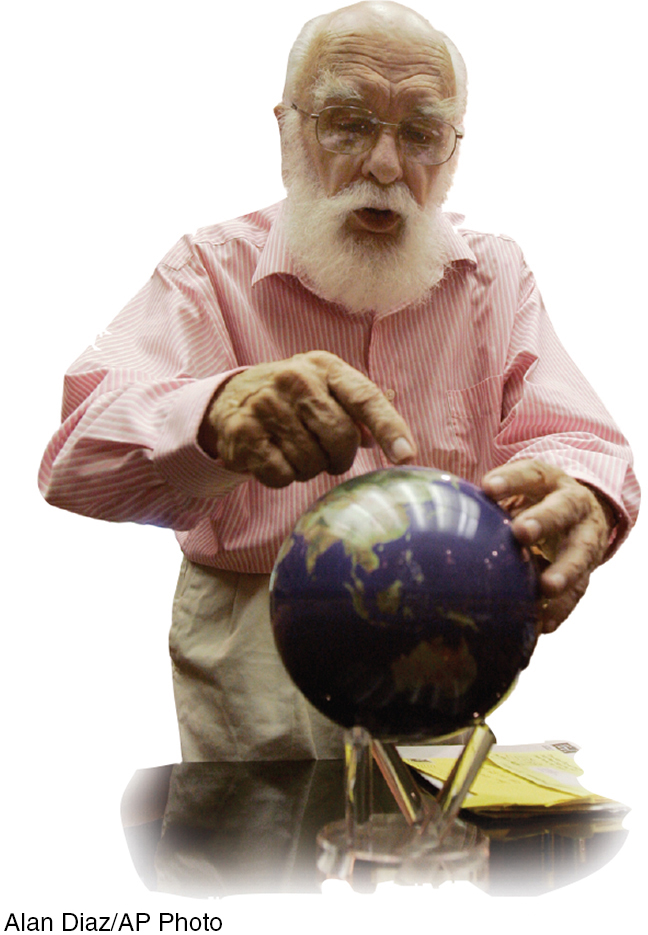

Magician and paranormal investigator James Randi has used this empirical approach when testing those claiming to see glowing auras around people’s bodies:

Randi: Do you see an aura around my head?

Aura seer: Yes, indeed.

Randi: Can you still see the aura if I put this magazine in front of my face?

Aura seer: Of course.

Randi: Then if I were to step behind a wall barely taller than I am, you could determine my location from the aura visible above my head, right?

Randi once told me [DM] that no aura seer had yet agreed to take this simple test.

No matter how sensible-

“To believe with certainty,” says a Polish proverb, “we must begin by doubting.” As scientists, psychologists approach the world of behavior with a curious skepticism, persistently asking two questions: What do you mean? How do you know?

Putting a scientific attitude into practice requires not only curiosity and skepticism but also humility—

Historians of science tell us that these three attitudes—

Of course, scientists, like anyone else, can have big egos and may cling to their preconceptions. It’s easy to get defensive when others challenge our cherished ideas. Nevertheless, the ideal of curious, skeptical, humble scrutiny of competing ideas unifies psychologists as a community as they check and recheck one another’s findings and conclusions.

“My deeply held belief is that if a god anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts … if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves.”

Carl Sagan, Broca’s Brain, 1979