2.1 The Need for Psychological Science

What About Intuition and Common Sense?

2-

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

Some people suppose that psychology merely documents and dresses in jargon what people already know: “You get paid for using fancy methods to prove what my grandmother knows?” Others place their faith in human intuition: “Buried deep within each and every one of us, there is an instinctive, heart-

So, are we smart to listen to the whispers of our inner wisdom, to simply trust “the force within”? Or should we more often be subjecting our intuitive hunches to skeptical scrutiny?

This much seems certain: We often underestimate intuition’s perils. My [DM’s] geographical intuition tells me that Reno is east of Los Angeles, that Rome is south of New York, that Atlanta is east of Detroit. But I am wrong, wrong, and wrong. As novelist Madeleine L’Engle observed, “The naked intellect is an extraordinarily inaccurate instrument” (1973). Three phenomena—

“Those who trust in their own wits are fools.”

Proverbs 28:26

“Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards.”

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, 1813-

DID WE KNOW IT ALL ALONG? HINDSIGHT BIAS Consider how easy it is to draw the bull’s-

“Anything seems commonplace, once explained.”

Dr. Watson to Sherlock Holmes

hindsight bias the tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that one would have foreseen it. (Also known as the I-

This hindsight bias (also known as the I-

Tell the second group the opposite: “Psychologists have found that separation strengthens romantic attraction. As the saying goes, ‘Absence makes the heart grow fonder.’” People given this untrue result can also easily imagine it, and most will also see it as unsurprising. When opposite findings both seem like common sense, there is a problem.

Such errors in our recollections and explanations show why we need psychological research. Just asking people how and why they felt or acted as they did can sometimes be misleading—

More than 800 scholarly papers have shown hindsight bias in people young and old from across the world (Roese & Vohs, 2012). Nevertheless, Grandma’s intuition is often right. As Yogi Berra once said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” (We have Berra to thank for other gems, such as “Nobody ever comes here—

OVERCONFIDENCE We humans tend to think we know more than we do. Asked how sure we are of our answers to factual questions (Is Boston north or south of Paris?), we tend to be more confident than correct.2 Or consider these three anagrams, which Richard Goranson (1978) asked people to unscramble:

| WREAT |

|

WATER |

| ETRYN |

|

ENTRY |

| GRABE |

|

BARGE |

About how many seconds do you think it would have taken you to unscramble each of these? Knowing the answers tends to make us overconfident. (Surely the solution would take only 10 seconds or so.) In reality, the average problem solver spends 3 minutes, as you also might, given a similar anagram without the solution: OCHSA.3

Overconfidence in history:

“We don’t like their sound. Groups of guitars are on their way out.”

Decca Records, in turning down a recording contract with the Beatles in 1962

Are we any better at predicting social behavior? Psychologist Philip Tetlock (1998, 2005) collected more than 27,000 expert predictions of world events, such as the future of South Africa or whether Quebec would separate from Canada. His repeated finding: These predictions, which experts made with 80 percent confidence on average, were right less than 40 percent of the time. Nevertheless, even those who erred maintained their confidence by noting they were “almost right”: “The Québécois separatists almost won the secessionist referendum.”

“Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.”

Popular Mechanics, 1949

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why, after friends start dating, do we often feel that we knew they were meant to be together?

“They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.”

General John Sedgwick just before being killed during a U.S. Civil War battle, 1864

“The telephone may be appropriate for our American cousins, but not here, because we have an adequate supply of messenger boys.”

British expert group evaluating the invention of the telephone

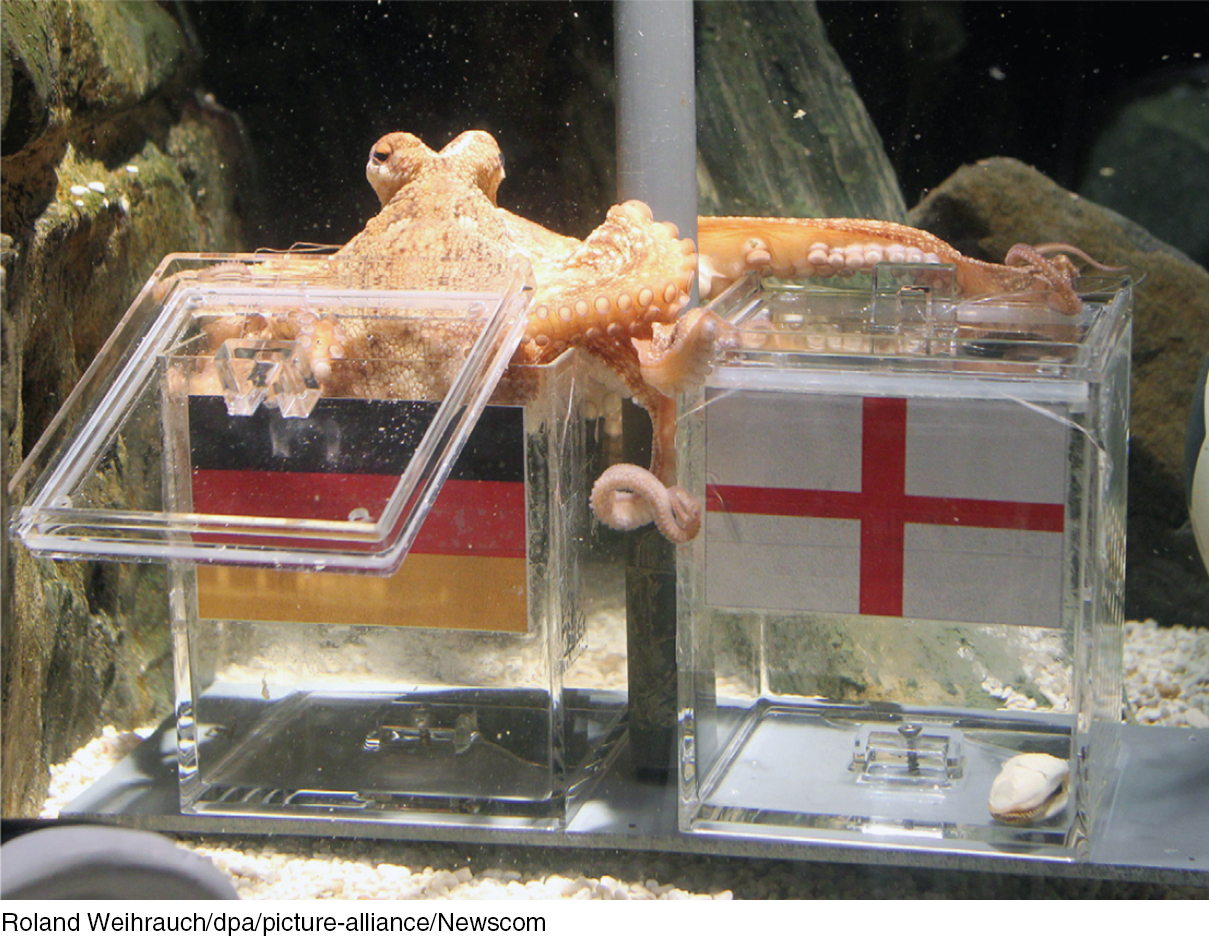

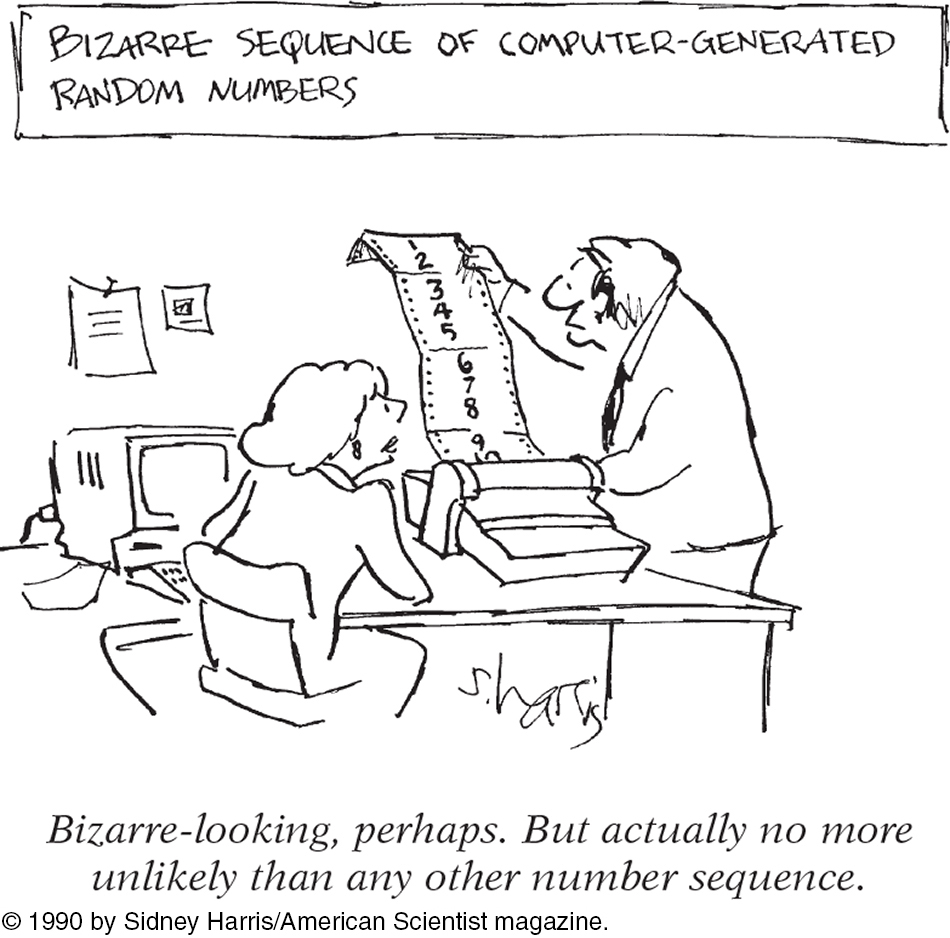

PERCEIVING ORDER IN RANDOM EVENTS We have a built-

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how scientific inquiry can help you think smarter about hot streaks in sports with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There Is a Hot Hand in Basketball?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how scientific inquiry can help you think smarter about hot streaks in sports with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There Is a Hot Hand in Basketball?

Some happenings, such as winning the lottery twice, seem so extraordinary that we find it difficult to conceive an ordinary, chance-

The point to remember: Hindsight bias, overconfidence, and our tendency to perceive patterns in random events often lead us to overestimate our intuition. But scientific inquiry can help us sift reality from illusion.