6.1 Behavior Genetics: Predicting Individual Differences

6-

Our shared brain architecture predisposes some common behavioral tendencies. Whether we live in the Arctic or the tropics, we sense the world, develop language, and feel hunger through identical mechanisms. We prefer sweet tastes to sour. We divide the color spectrum into similar colors. And we feel drawn to behaviors that produce and protect offspring.

Our human family shares not only a common biological heritage—

environment every nongenetic influence, from prenatal nutrition to the people and things around us.

heredity the genetic transfer of characteristics from parents to offspring.

behavior genetics the study of the relative power and limits of genetic and environmental influences on behavior.

But in important ways, we also are each unique. We look different. We sound different. We have varying personalities, interests, and cultural and family backgrounds. What causes our striking diversity? How much of it is shaped by our differing genes, and how much by our environment—by every external influence, from maternal nutrition while in the womb to social support while nearing the tomb? How does our heredity interact with our experiences to create both our universal human nature and our individual and social diversity? Such questions intrigue behavior geneticists.

Genes: Our Codes for Life

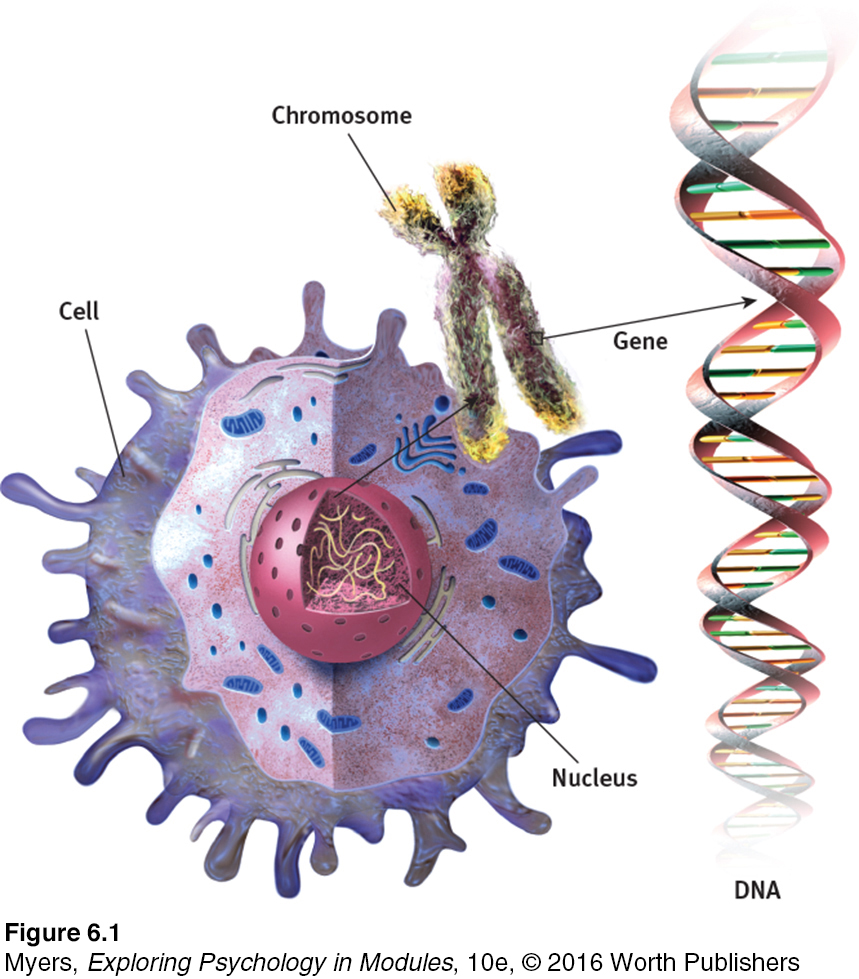

chromosomes threadlike structures made of DNA molecules that contain the genes.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) a complex molecule containing the genetic information that makes up the chromosomes.

genes the biochemical units of heredity that make up the chromosomes; segments of DNA capable of synthesizing proteins.

genome the complete instructions for making an organism, consisting of all the genetic material in that organism’s chromosomes.

Barely more than a century ago, few would have guessed that every cell nucleus in your body contains the genetic master code for your entire body. It’s as if every room in Dubai’s Burj Khalifa (the world’s tallest building) contained a book detailing the architect’s plans for the entire structure. The plans for your own book of life run to 46 chapters—

Genetically speaking, every other human is nearly your identical twin. Human genome researchers have discovered the common sequence within human DNA. This shared genetic profile makes us humans, rather than tulips, bananas, or chimpanzees.

“We share half our genes with the banana.”

Evolutionary biologist Robert May, president of Britain’s Royal Society, 2001

The occasional variations found at particular gene sites in human DNA fascinate geneticists and psychologists. Slight person-

Most of our traits have complex genetic roots. How tall you are, for example, reflects the size of your face, vertebrae, leg bones, and so forth—

“Your DNA and mine are 99.9 percent the same. . . . At the DNA level, we are clearly all part of one big worldwide family.”

Francis Collins, Human Genome Project director, 2007

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Put the following cell structures in order from smallest to largest: nucleus, gene, chromosome

Question

When the mother's egg and the father's sperm unite, each contributes 23 .

Twin and Adoption Studies

6-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies, below for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies, below for a helpful tutorial animation.

To scientifically tease apart the influences of environment and heredity, behavior geneticists could wish for two types of experiments. The first would control heredity while varying the home environment. The second would control the home environment while varying heredity. Although such experiments with human infants would be unethical, nature has done this work for us.

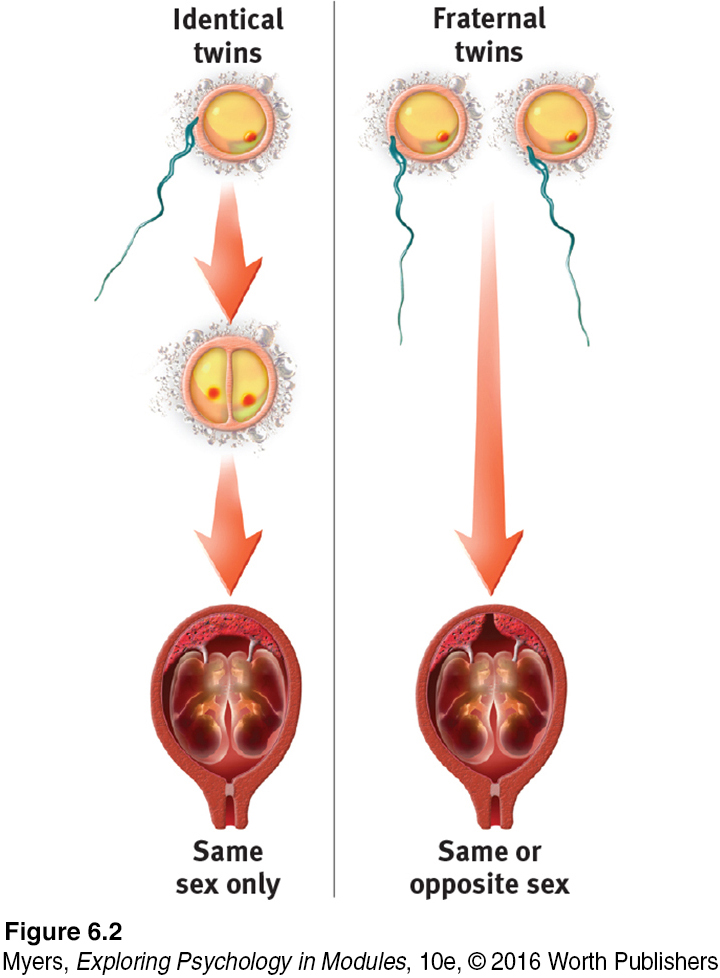

identical (monozygotic) twins develop from a single fertilized egg that splits in two, creating two genetically identical organisms.

IDENTICAL VERSUS FRATERNAL TWINS Identical (monozygotic) twins develop from a single fertilized egg that splits in two. Thus they are genetically identical—

fraternal (dizygotic) twins develop from separate fertilized eggs. They are genetically no closer than ordinary brothers and sisters, but they share a prenatal environment.

Fraternal (dizygotic) twins develop from two separate fertilized eggs. As womb-

Shared genes can translate into shared experiences. A person whose identical twin has autism spectrum disorder, for example, has about a 3 in 4 risk of being similarly diagnosed. If the affected twin is fraternal, the co-

Are genetically identical twins also behaviorally more similar than fraternal twins? Studies of thousands of twin pairs have found that identical twins are much more alike in extraversion (outgoingness) and neuroticism (emotional instability) than are fraternal twins (Kandler et al., 2011; Laceulle et al., 2011; Loehlin, 2012).

Identical twins, more than fraternal twins, look alike. So, do people’s responses to their looks account for their similarities? No. In one clever study, a researcher compared personality similarity between identical twins and unrelated look-

SEPARATED TWINS Imagine the following science fiction experiment: A mad scientist decides to separate identical twins at birth, then raise them in differing environments. Better yet, consider a true story:

On a chilly February morning in 1979, some time after divorcing his first wife, Linda, Jim Lewis awoke in his modest home next to his second wife, Betty. Determined to make this marriage work, Jim made a habit of leaving love notes to Betty around the house. As he lay in bed he thought about others he had loved, including his son, James Alan, and his faithful dog, Toy.

Twins Lorraine and Levinia Christmas, driving to deliver Christmas presents to each other near Flitcham, England, collided (Shepherd, 1997).

Jim looked forward to spending part of the day in his basement woodworking shop, where he enjoyed building furniture, picture frames, and other items, including a white bench now circling a tree in his front yard. Jim also liked to spend free time driving his Chevy, watching stock car racing, and drinking Miller Lite beer.

Jim was basically healthy, except for occasional half-

What was extraordinary about Jim Lewis, however, was that at that same moment (we are not making this up) there existed another man—

One month later, the brothers became the first of many separated twin pairs tested by University of Minnesota psychologist Thomas Bouchard and his colleagues (Miller, 2012). The brothers’ voice intonations and inflections were so similar that, hearing a playback of an earlier interview, Jim Springer guessed “That’s me.” Wrong—

In 2009, thieves broke into a Berlin store and stole jewelry worth $6.8 million. One thief left a drop of sweat—

Aided by media publicity, Bouchard (2009) and his colleagues located and studied 74 pairs of identical twins raised apart. They continued to find similarities not only of tastes and physical attributes but also of personality (characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting), abilities, attitudes, interests, and even fears.

In Sweden, researchers identified 99 separated identical twin pairs and more than 200 separated fraternal twin pairs (Pedersen et al., 1988). Compared with equivalent samples of identical twins raised together, the separated identical twins had somewhat less identical personalities. Still, separated twins were more alike if genetically identical than if fraternal. And separation shortly after birth (rather than, say, at age 8) did not amplify their personality differences.

Coincidences are not unique to twins. Patricia Kern of Colorado was born March 13, 1941, and named Patricia Ann Campbell. Patricia DiBiasi of Oregon also was born March 13, 1941, and named Patricia Ann Campbell. Both had fathers named Robert, worked as bookkeepers, and at the time of this comparison had children ages 21 and 19. Both studied cosmetology, enjoyed oil painting as a hobby, and married military men, within 11 days of each other. They are not genetically related. (From an AP report, May 2, 1983.)

Stories of startling twin similarities have not impressed critics, who remind us that “The plural of anecdote is not data.” They note that if any two strangers were to spend hours comparing their behaviors and life histories, they would probably discover many coincidental similarities. If researchers created a control group of biologically unrelated pairs of the same age, sex, and ethnicity, who had not grown up together but who were as similar to one another in economic and cultural background as are many of the separated twin pairs, wouldn’t these pairs also exhibit striking similarities (Joseph, 2001)? Twin researchers have replied that separated fraternal twins do not exhibit similarities comparable with those of separated identical twins.

The impressive data from personality assessments are clouded by the reunion of many of the separated twins some years before they were tested. And adoption agencies also tend to place separated twins in similar homes. Despite these criticisms, the striking twin-

If genetic influences help explain individual differences, can the same be said of trait differences between groups? Not necessarily. Individual differences in height and weight, for example, are highly heritable; yet nutrition (an environmental factor) rather than genetic influences explains why, as a group, today’s adults are taller and heavier than those of a century ago. The two groups differ, but not because human genes have changed in a mere century’s eyeblink of time. Ditto aggressiveness, a genetically influenced trait. Today’s peaceful Scandinavians differ from their more aggressive Viking ancestors, despite carrying many of the same genes.

BIOLOGICAL VERSUS ADOPTIVE RELATIVES For behavior geneticists, nature’s second real-

The stunning finding from studies of hundreds of adoptive families is that, with the exception of identical twins, people who grow up together do not much resemble one another in personality (McGue & Bouchard, 1998; Plomin, 2011; Rowe, 1990). In personality traits such as extraversion and agreeableness, people who have been adopted are more similar to their biological parents than to their caregiving adoptive parents.

The finding is important enough to bear repeating: The environment shared by a family’s children has virtually no discernible impact on their personalities. Two adopted children raised in the same home are no more likely to share personality traits with each other than with the child down the block. Heredity shapes other primates’ personalities, too. Macaque monkeys raised by foster mothers exhibited social behaviors that resembled their biological, rather than foster, mothers (Maestripieri, 2003). Add in the similarity of identical twins, whether they grow up together or apart, and the effect of a shared environment seems shockingly modest.

The genetic leash may limit the family environment’s influence on personality, but it does not mean that adoptive parenting is a fruitless venture. As a new adoptive parent, I [ND] especially find it heartening to know that parents do influence their children’s attitudes, values, manners, politics, and faith (Reifman & Cleveland, 2007). Religious involvement is genetically influenced (Steger et al., 2011). But a pair of adopted children or identical twins will, especially during adolescence, have more similar religious beliefs if raised together (Koenig et al., 2005). Parenting matters!

Moreover, child neglect and abuse and even parental divorce are rare in adoptive homes. (Adoptive parents are carefully screened; biological parents are not.) So it is not surprising that studies have shown that, despite a slightly greater risk of psychological disorder, most adopted children thrive, especially when adopted as infants (Loehlin et al., 2007; van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2006; Wierzbicki, 1993). Seven in eight adopted children have reported feeling strongly attached to one or both adoptive parents. As children of self-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How do researchers use twin and adoption studies to learn about psychological principles?

Gene-Environment Interaction

6-

Among our similarities, the most important—

“Men’s natures are alike; it is their habits that carry them far apart.”

Confucius, Analects, 500 B.C.E.

Genes and environment—

interaction the interplay that occurs when the effect of one factor (such as environment) depends on another factor (such as heredity).

To say that genes and experience are both important is true. But more precisely, they interact. Imagine two babies, one genetically predisposed to be attractive, sociable, and easygoing, the other less so. Assume further that the first baby attracts more affectionate and stimulating care and so develops into a warmer and more outgoing person. As the two children grow older, the more naturally outgoing child may seek more activities and friends that encourage further social confidence.

What has caused their resulting personality differences? Neither heredity nor experience act alone. Environments trigger gene activity. And our genetically influenced traits evoke significant responses in others. Thus, a child’s impulsivity and aggression may evoke an angry response from a parent or teacher, who reacts warmly to well-

Identical twins not only share the same genetic predispositions, they also seek and create similar experiences that express their shared genes (Kandler et al., 2012). Evocative interactions may help explain why identical twins raised in different families have recalled their parents’ warmth as remarkably similar—

epigenetics the study of environmental influences on gene expression that occur without a DNA change.

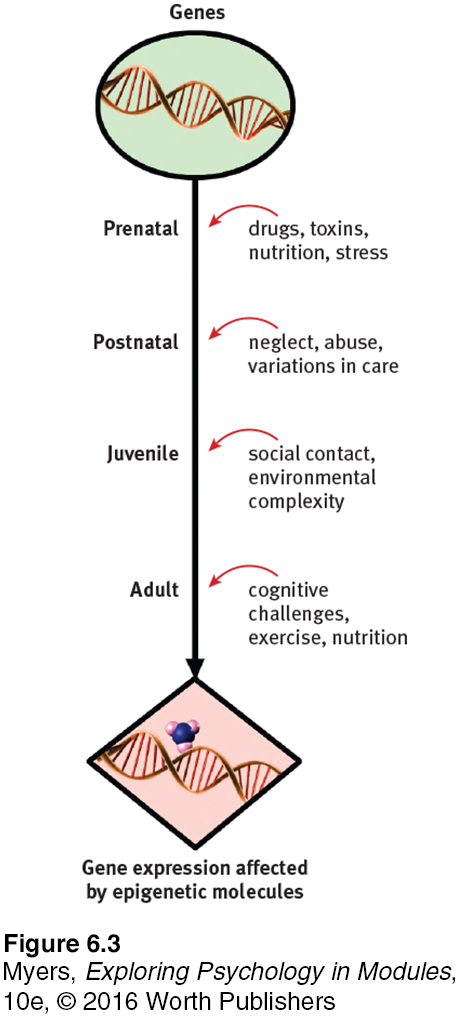

Recall that genes can be either active (expressed, as the hot water activates the tea bag) or inactive. Epigenetics (meaning “in addition to” or “above and beyond” genetics), studies the molecular mechanisms by which environments can trigger or block genetic expression. Our experiences create epigenetic marks, which are often organic methyl molecules attached to part of a DNA strand (FIGURE 6.3). If a mark instructs the cell to ignore any gene present in that DNA segment, those genes will be “turned off”—they will prevent the DNA from producing the proteins coded by that gene. As one geneticist said, “Things written in pen you can’t change. That’s DNA. Things written in pencil you can. That’s epigenetics” (Read, 2012).

Environmental factors such as diet, drugs, and stress can affect the epigenetic molecules that regulate gene expression. Mother rats normally lick their infants. Deprived of this licking in experiments, infant rats had more epigenetic molecules blocking access to their brain’s “on” switch for developing stress hormone receptors. When stressed, those animals had above-

Epigenetics can also help explain why identical twins may look slightly different. Researchers studying mice have found that in utero exposure to certain chemicals can cause genetically identical twins to have different-

For a 7-

For a 7-

So, if Beyoncé and Jay Z’s daughter, Blue Ivy, grows up to be a popular recording artist, should we attribute her musical talent to her “superstar genes”? To her growing up in a musically rich environment? To high expectations? The best answer seems to be “All of the above.” From conception onward, we are the product of a cascade of interactions between our genetic predispositions and our surrounding environments (McGue, 2010). Our genes affect how people react to and influence us. Forget nature versus nurture; think nature via nurture.

RETRIEVE IT

Match the following terms to the correct explanation.

Question

Epigenetics Behavior genetics | Study of the relative effects of our genes and our environment on our behavior. Study of environmental factors that affect how our genes are expressed. |