8.4 Dreams

Now playing at an inner theater near you: the premiere showing of a sleeping person’s vivid dream. This never-

Waking from a troubling dream (you were late to something and your legs weren’t working), who among us has not wondered about this weird state of consciousness? How can our brain so creatively, colorfully, and completely construct this alternative world? In the shadowland between our dreaming and waking consciousness, we may even wonder for a moment which is real.

Discovering the link between REM sleep and dreaming ushered in a new era in dream research. Instead of relying on someone’s hazy recall hours or days after having a dream, researchers could catch dreams as they happened. They could awaken people during or within 3 minutes after a REM sleep period and hear a vivid account.

What We Dream

8-

dream a sequence of images, emotions, and thoughts passing through a sleeping person’s mind.

Daydreams tend to involve the familiar detailsof our life—

“I do not believe that I am now dreaming, but I cannot prove that I am not.”

Philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–

We spend 6 years of our life in dreams, many of which are anything but sweet. For both women and men, 8 in 10 dreams are marked by at least one negative event or emotion (Domhoff, 2007). Common themes include repeatedly failing in an attempt to do something; being attacked, pursued, or rejected; or experiencing misfortune (Hall et al., 1982). Dreams with sexual imagery occur less often than you might think. In one study, only 1 in 10 dreams among young men and 1 in 30 among young women had sexual content (Domhoff, 1996).

More commonly, a dream’s story line incorporates traces of previous days’ nonsexual experiences and preoccupations (De Koninck, 2000):

After suffering a trauma, people commonly report nightmares, which help extinguish daytime fears (Levin & Nielsen, 2007, 2009). One sample of Americans recording their dreams during September, 2001 reported an increase in threatening dreams following the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Propper et al., 2007).

“For what one has dwelt on by day, these things are seen in visions of the night.”

Menander of Athens (342–

Compared with city dwellers, people in hunter-

gatherer societies more often dream of animals (Mestel, 1997). Compared with nonmusicians, musicians report twice as many dreams of music (Uga et al., 2006). Studies in four countries have found blind people mostly dreaming of using their nonvisual senses (Buquet, 1988; Taha, 1972; Vekassy, 1977). But even natively blind people sometimes “see” in their dreams (Bértolo, 2005). Likewise, people born paralyzed below the waist sometimes dream of walking, standing, running, or cycling (Saurat et al., 2011; Voss et al., 2011).

Our two-

A popular sleep myth: If you dream you are falling and hit the ground (or if you dream of dying), you die. Unfortunately, those who could confirm these ideas are not around to do so. Many people, however, have had such dreams and are alive to report them.

So, could we learn a foreign language by hearing it played while we sleep? If only. While sleeping, we can learn to associate a sound with a mild electric shock (and to react to the sound accordingly). We can also learn to associate a particular sound with a pleasant or unpleasant odor (Arzi et al., 2012). But we do not remember recorded information played while we are soundly asleep (Eich, 1990; Wyatt & Bootzin, 1994). In fact, anything that happens during the 5 minutes just before we fall asleep is typically lost from memory (Roth et al., 1988). This explains why sleep apnea patients, who repeatedly awaken with a gasp and then immediately fall back to sleep, do not recall the episodes. Ditto someone who awakens momentarily, sends a text message, and the next day can’t remember doing so. It also explains why dreams that momentarily awaken us are mostly forgotten by morning. To remember a dream, get up and stay awake for a few minutes.

“Follow your dreams, except for that one where you’re naked at work.”

Attributed to comedian Henny Youngman

Why We Dream

8-

Dream theorists have proposed several explanations of why we dream, including these five:

manifest content according to Freud, the remembered story line of a dream (as distinct from its latent, or hidden, content).

latent content according to Freud, the underlying meaning of a dream (as distinct from its manifest content).

To satisfy our own wishes. In 1900, in his landmark book The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud offered what he thought was “the most valuable of all the discoveries it has been my good fortune to make.” He proposed that dreams provide a psychic safety valve that discharges otherwise unacceptable feelings. He viewed a dream’s manifest content (the apparent and remembered story line) as a censored, symbolic version of its latent content, the unconscious drives and wishes that would be threatening if expressed directly. Although most dreams have no overt sexual imagery, Freud nevertheless believed that most adult dreams could be “traced back by analysis to erotic wishes.” Thus, a gun might be a disguised representation of a penis.

“When people interpret [a dream] as if it were meaningful and then sell those interpretations, it’s quackery.”

Sleep researcher J. Allan Hobson (1995)

Freud considered dreams the key to understanding our inner conflicts. However, his critics say it is time to wake up from Freud’s dream theory, which they regard as a scientific nightmare. Based on the accumulated science, “there is no reason to believe any of Freud’s specific claims about dreams and their purposes,” observed dream researcher William Domhoff (2003). Some contend that even if dreams are symbolic, they could be interpreted any way one wished. Others maintain that dreams hide nothing. A dream about a gun is a dream about a gun. Legend has it that even Freud, who loved to smoke cigars, acknowledged that “sometimes, a cigar is just a cigar.” Freud’s wish-

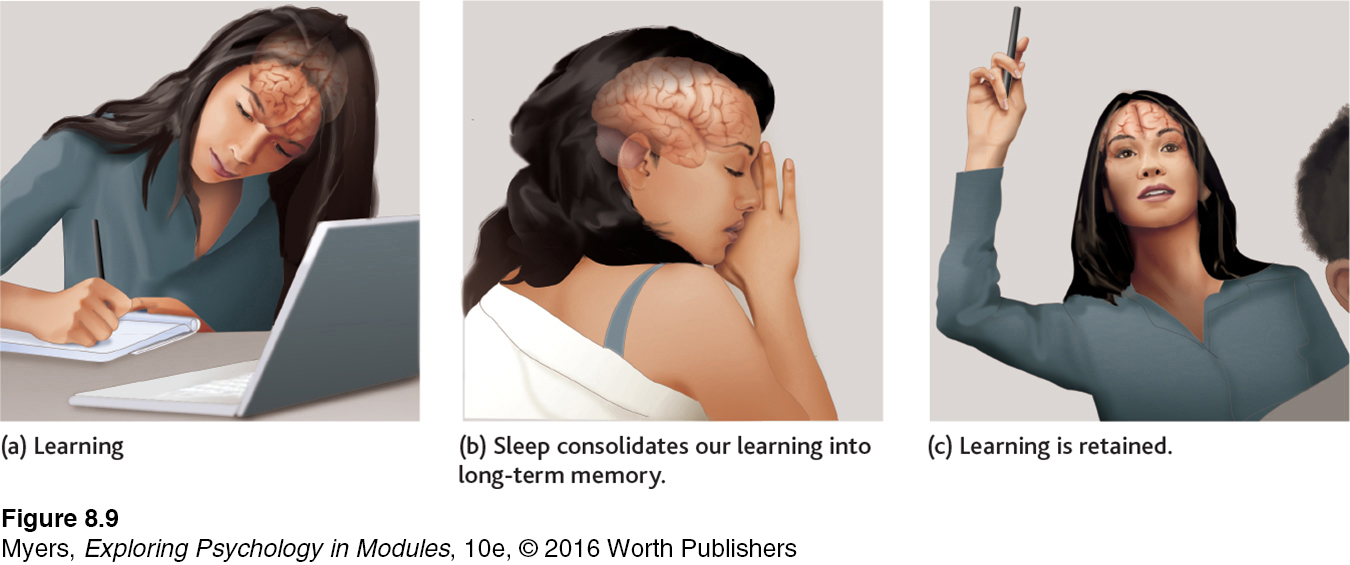

To file away memories. The information-

Brain scans confirm the link between REM sleep and memory. The brain regions that buzzed as rats learned to navigate a maze, or as people learned to perform a visual-

This is important news for students, many of whom, observed researcher Robert Stickgold (2000), suffer from a kind of sleep bulimia—

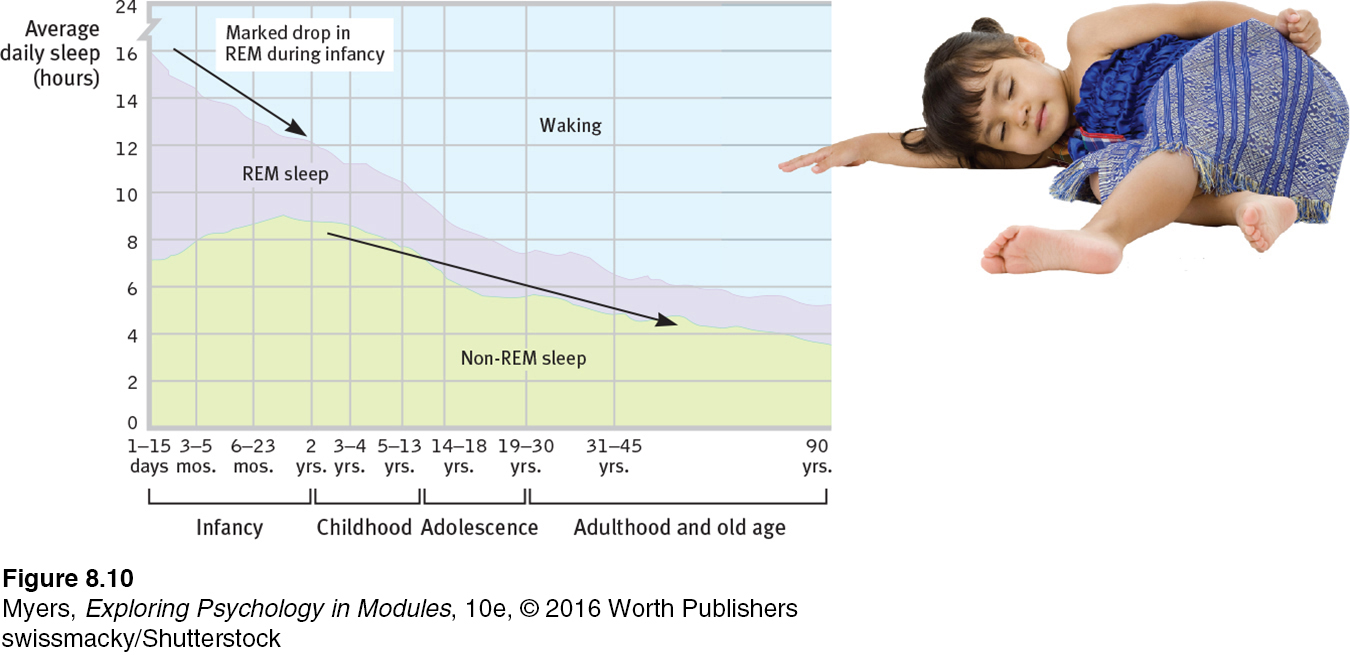

To develop and preserve neural pathways. Perhaps dreams, or the brain activity associated with REM sleep, serve a physiological function, providing the sleeping brain with periodic stimulation. This theory makes developmental sense. Stimulating experiences preserve and expand the brain’s neural pathways. Infants, whose neural networks are fast developing, spend much of their abundant sleep time in REM sleep (FIGURE 8.10).

Rapid eye movements also stir the liquid behind the cornea; this delivers fresh oxygen to corneal cells, preventing their suffocation.

To make sense of neural static. Other theories propose that dreams erupt from neural activation spreading upward from the brainstem (Antrobus, 1991; Hobson, 2003, 2004, 2009). According to “activation-

Question: Does eating spicy foods cause us to dream more?

Answer: Any food that causes you to awaken more increases your chance of recalling a dream (Moorcroft, 2003).

To reflect cognitive development. Some dream researchers dispute both the Freudian and neural activation theories, preferring instead to see dreams as part of brain maturation and cognitive development (Domhoff, 2010, 2011; Foulkes, 1999). For example, prior to age 9, children’s dreams seem more like a slide show and less like an active story in which the dreamer is an actor. Dreams overlap with waking cognition and feature coherent speech. They simulate reality by drawing on our concepts and knowledge. They engage brain networks that also are active during daydreaming—

REM rebound the tendency for REM sleep to increase following REM sleep deprivation.

TABLE 8.2 compares these major dream theories. Although today’s sleep researchers debate dreams’ functions—

Dream Theories

| Theory | Explanation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Freud’s wish- |

Dreams preserve sleep and provide a “psychic safety valve”—expressing otherwise unacceptable feelings; contain manifest (remembered) content and a deeper layer of latent content (a hidden meaning). | Lacks any scientific support; dreams may be interpreted in many different ways. |

| Information- |

Dreams help us sort out the day’s events and consolidate our memories. | But why do we sometimes dream about things we have not experienced and about past events? |

| Physiological function | Regular brain stimulation from REM sleep may help develop and preserve neural pathways. | This does not explain why we experience meaningful dreams. |

| Neural activation | REM sleep triggers neural activity that evokes random visual memories, which our sleeping brain weaves into stories. | The individual’s brain is weaving the stories, which still tells us something about the dreamer. |

| Cognitive development | Dream content reflects dreamers’ level of cognitive development— |

Does not propose an adaptive function of dreams. |

So does this mean that because dreams serve physiological functions and extend normal cognition, they are psychologically meaningless? Not necessarily. Every psychologically meaningful experience involves an active brain. We are once again reminded of a basic principle: Biological and psychological explanations of behavior are partners, not competitors.

Dreams are a fascinating altered state of consciousness. But they are not the only altered state. As we will see next, drugs also alter conscious awareness.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What five theories propose explanations for why we dream?