7.4 Dual Processing: The Two-Track Mind

7-

Discovering which brain region becomes active with a particular conscious experience strikes many people as interesting, but not mind blowing. (If everything psychological is simultaneously biological, then our ideas, emotions, and spirituality must all, somehow, be embodied.) What is mind blowing to many of us is the growing evidence that we have, so to speak, two minds, each supported by its own neural equipment.

dual processing the principle that information is often simultaneously processed on separate conscious and unconscious tracks.

At any moment, we are aware of little more than what’s on the screen of our consciousness. But beneath the surface, unconscious information processing occurs simultaneously on many parallel tracks. When we look at a bird flying, we are consciously aware of the result of our cognitive processing (“It’s a hummingbird!”) but not of our subprocessing of the bird’s color, form, movement, and distance. One of the grand ideas of recent cognitive neuroscience is that much of our brain work occurs off stage, out of sight. Perception, memory, thinking, language, and attitudes all operate on two levels—

If you are a driver, consider how you move into a right lane. Drivers know this unconsciously but cannot accurately explain it (Eagleman, 2011). Most say they would bank to the right, then straighten out—

blindsight a condition in which a person can respond to a visual stimulus without consciously experiencing it.

Or consider this story, which illustrates how science can be stranger than science fiction. During my sojourns at Scotland’s University of St Andrews, I [DM] came to know cognitive neuroscientists David Milner and Melvyn Goodale (2008). A local woman, whom they called D. F., suffered brain damage when overcome by carbon monoxide, leaving her unable to recognize and discriminate objects visually. Consciously, D. F. could see nothing. Yet she exhibited blindsight—she acted as though she could see. Asked to slip a postcard into a vertical or horizontal mail slot, she could do so without error. Asked the width of a block in front of her, she was at a loss, but she could grasp it with just the right finger-

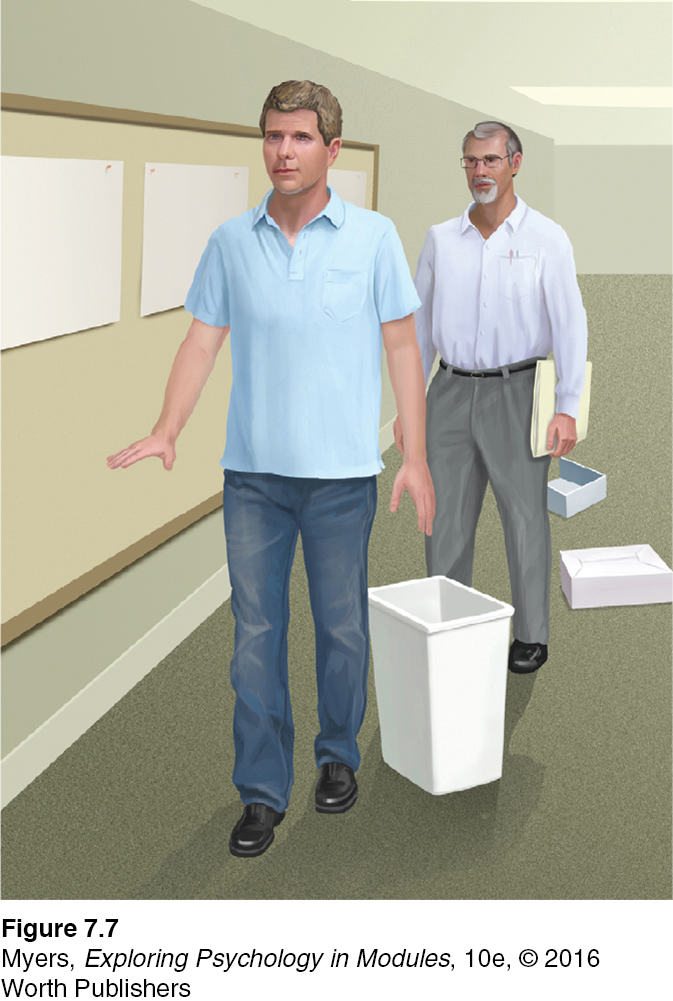

How could this be? Don’t we have one visual system? Goodale and Milner knew from animal research that the eye sends information simultaneously to different brain areas, which support different tasks (Weiskrantz, 2009, 2010). Sure enough, a scan of D. F.’s brain activity revealed normal activity in the area concerned with reaching for, grasping, and navigating objects, but damage in the area concerned with consciously recognizing objects. (See another example in FIGURE 7.7.)

How strangely intricate is this thing we call vision, conclude Goodale and Milner in their aptly titled book, Sight Unseen (2004). We may think of our vision as a single system that controls our visually guided actions. Actually, it is a dual-

The dual-

People often have trouble accepting that much of our everyday thinking, feeling, and acting operates outside our conscious awareness (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999). Some “80 to 90 percent of what we do is unconscious,” says Nobel Laureate and memory expert Eric Kandel (2008). We are understandably inclined to believe that our intentions and deliberate choices rule our lives. But consciousness, though enabling us to exert voluntary control and to communicate our mental states to others, is but the tip of the information-

To think further about conscious awareness and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s Psych-

To think further about conscious awareness and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s Psych-

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Parallel processing enables your mind to take care of routine business. Unconscious parallel processing is faster than conscious sequential processing, but both are essential. Sequential processing is best for solving new problems, which requires your focused attention. Try this: If you are right-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are the mind's two tracks, and what is dual processing?