12.3 Social Development

12-

“Somewhere between the ages of 10 and 13 (depending on how hormone-

Jon Stewart et al.,

Earth (The Book), 2010

Theorist Erik Erikson (1963) contended that each stage of life has its own psychosocial task, a crisis that needs resolution. Young children wrestle with issues of trust, then autonomy (independence), then initiative. School-

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

| Stage (approximate age) | Issue | Description of Task |

|---|---|---|

| Infancy (to 1 year) | Trust vs. mistrust | If needs are dependably met, infants develop a sense of basic trust. |

| Toddlerhood (1 to 3 years) | Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Toddlers learn to exercise their will and do things for themselves, or they doubt their abilities. |

| Preschool (3 to 6 years) | Initiative vs. guilt | Preschoolers learn to initiate tasks and carry out plans, or they feel guilty about their efforts to be independent. |

| Elementary school (6 years to puberty) | Competence vs. inferiority | Children learn the pleasure of applying themselves to tasks, or they feel inferior. |

| Adolescence (teen years into 20s) | Identity vs. role confusion | Teenagers work at refining a sense of self by testing roles and then integrating them to form a single identity, or they become confused about who they are. |

| Young adulthood (20s to early 40s) | Intimacy vs. isolation | Young adults struggle to form close relationships and to gain the capacity for intimate love, or they feel socially isolated. |

| Middle adulthood (40s to 60s) | Generativity vs. stagnation | In middle age, people discover a sense of contributing to the world, usually through family and work, or they may feel a lack of purpose. |

| Late adulthood (late 60s and up) | Integrity vs. despair | Reflecting on their lives, older adults may feel a sense of satisfaction or failure. |

Forming an Identity

identity our sense of self; according to Erikson, the adolescent’s task is to solidify a sense of self by testing and integrating various roles.

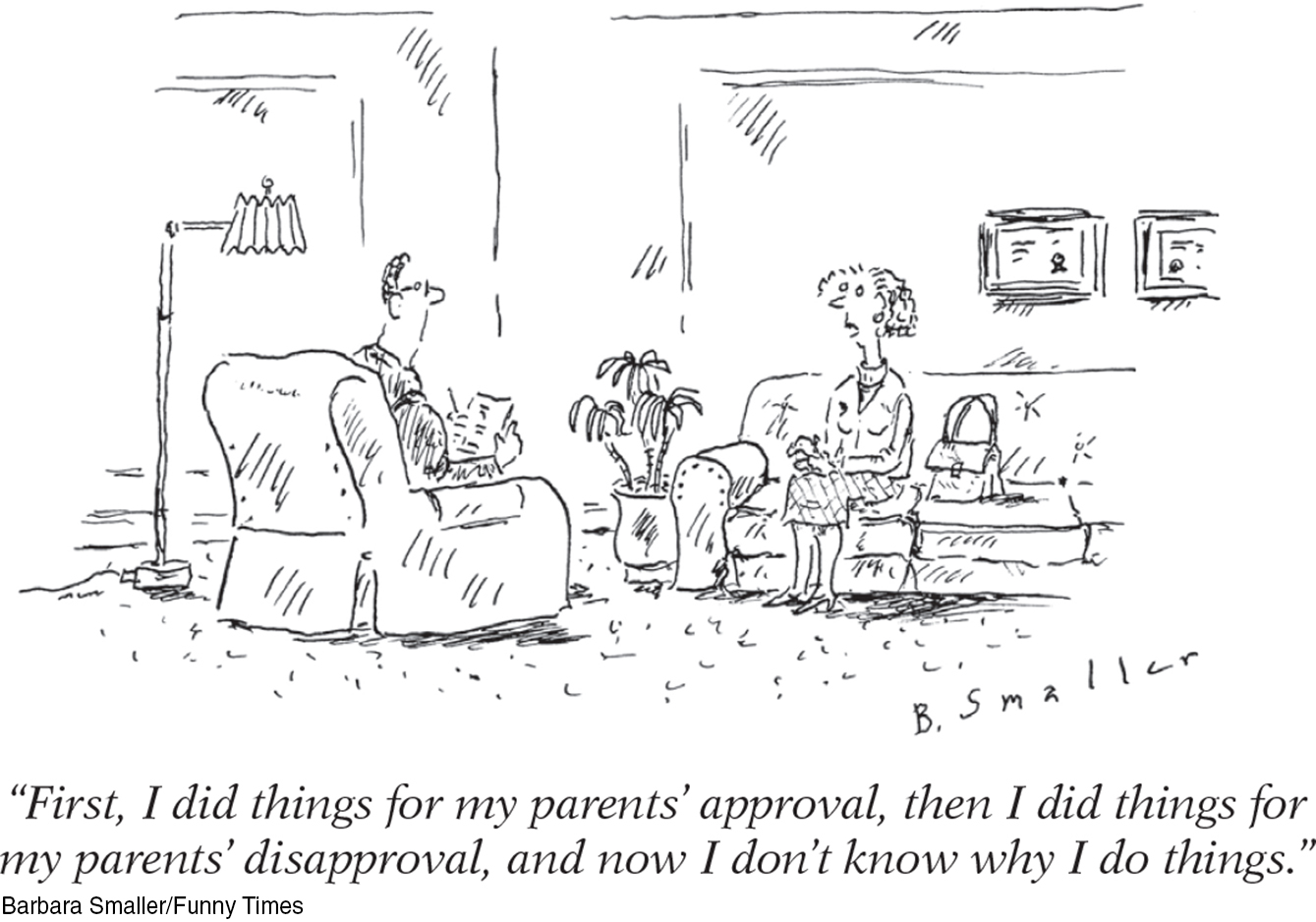

To refine their sense of identity, adolescents in individualist cultures usually try out different “selves” in different situations. They may act out one self at home, another with friends, and still another at school or online. If two situations overlap—

social identity the “we” aspect of our self-

For both adolescents and adults, group identities are often formed by how we differ from those around us. When living in Britain, I [DM] become conscious of my Americanness. When spending time with collaborators in Hong Kong, I [ND] become conscious of my minority White race. When surrounded by women, we are both mindful of our male gender identity. For international students, for those of a minority ethnic group, for gay and transgender people, or for people with a disability, a social identity often forms around their distinctiveness.

Erikson noticed that some adolescents forge their identity early, simply by adopting their parents’ values and expectations. (Traditional, less individualist cultures teach adolescents who they are, rather than encouraging them to decide on their own.) Other adolescents may adopt the identity of a particular peer group—

“Self-

C. S. Lewis,

The Problem of Pain, 1940

Most young people do develop a sense of contentment with their lives. A question: Which statement best describes you? “I would choose my life the way it is right now” or, “I wish I were somebody else”? When American teens answered, 81 percent picked the first, and 19 percent the second (Lyons, 2004). Reflecting on their existence, 75 percent of American collegians say they “discuss religion/spirituality” with friends, “pray,” and agree that “we are all spiritual beings” and “search for meaning/purpose in life” (Astin et al., 2004; Bryant & Astin, 2008). This would not surprise Stanford psychologist William Damon and his colleagues (2003), who have contended that a key task of adolescence is to achieve a purpose—

Several nationwide studies indicate that young Americans’ self-

These are the years when many people in industrialized countries begin exploring new opportunities by attending college or working full time. Many college seniors have achieved a clearer identity and a more positive self-

intimacy in Erikson’s theory, the ability to form close, loving relationships; a primary developmental task in young adulthood.

For an interactive self-

For an interactive self-

Erikson contended that adolescent identity formation (which continues into adulthood) is followed in young adulthood by a developing capacity for intimacy, the ability to form emotionally close relationships. When Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [chick-

Parent and Peer Relationships

12-

As adolescents in Western cultures seek to form their own identities, they begin to pull away from their parents (Shanahan et al., 2007). The preschooler who can’t be close enough to her mother, who loves to touch and cling to her, becomes the 14-

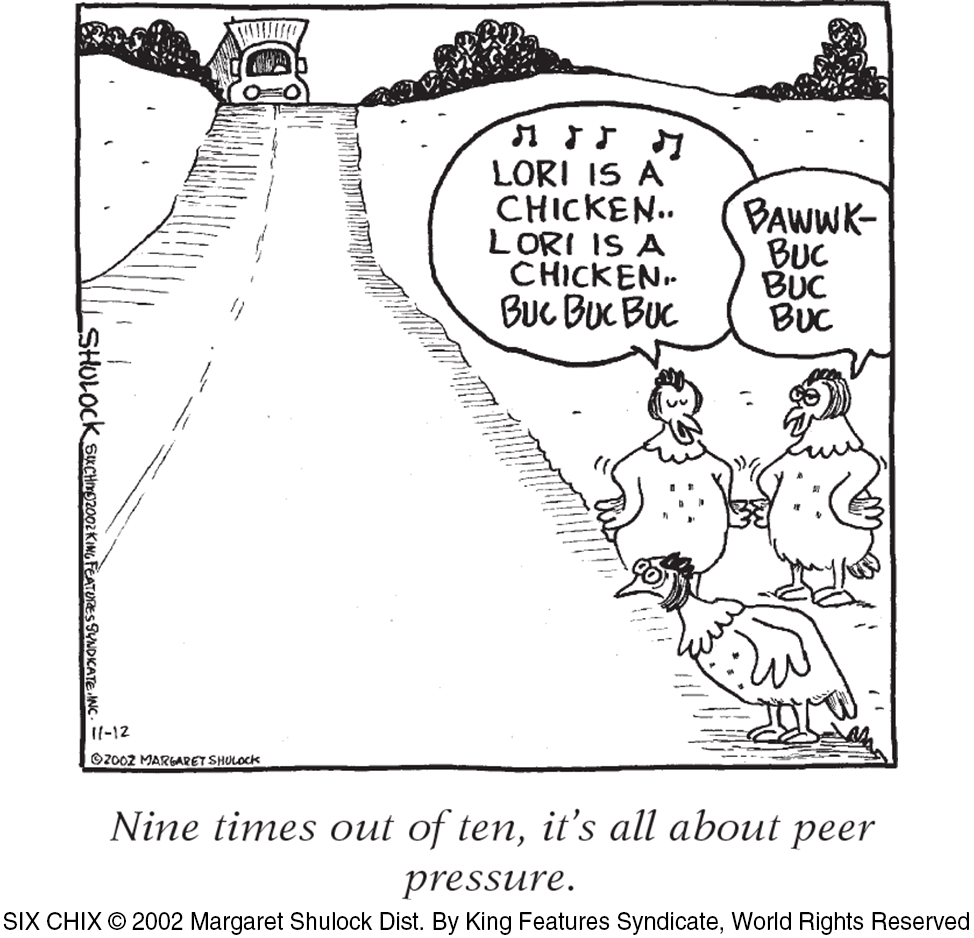

As Aristotle long ago recognized, we humans are “the social animal.” At all ages, but especially during childhood and adolescence, we seek to fit in with our groups (Harris, 1998, 2002). Teens who start smoking typically have friends who model smoking, suggest its pleasures, and offer cigarettes (J. S. Rose et al., 1999; R. J. Rose et al., 2003). Part of this peer similarity may result from a selection effect, as kids seek out peers with similar attitudes and interests. Those who smoke (or don’t) may select as friends those who also smoke (or don’t). Put two teens together and their brains become hypersensitive to reward (Albert et al., 2013). This increased activation helps explain why teens take more driving risks when with friends than they do alone (Chein et al., 2011).

“Men resemble the times more than they resemble their fathers.”

Ancient Arab proverb

By adolescence, parent-

For a minority of parents and their adolescents, differences lead to real splits and great stress (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). But most disagreements are at the level of harmless bickering. With sons, the issues often are behavior problems, such as acting out or hygiene; for daughters, the issues commonly involve relationships, such as dating and friendships (Schlomer et al., 2011). Most adolescents—

“I love u guys.”

Emily Keyes’ final text message to her parents before dying in a Colorado school shooting, 2006

Positive parent-

Although heredity does much of the heavy lifting in forming individual temperament and personality differences, parents and peers influence teen’s behaviors and attitudes (See Thinking Critically About: How Much Credit or Blame Do Parents Deserve?)

When with peers, teens discount the future and focus more on immediate rewards (O’Brien et al., 2011). Most teens are herd animals, talking, dressing, and acting more like their peers than their parents. What their friends are, they often become, and what “everybody’s doing,” they often do.

Part of what everybody’s doing is networking—

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

How Much Credit or Blame Do Parents Deserve?

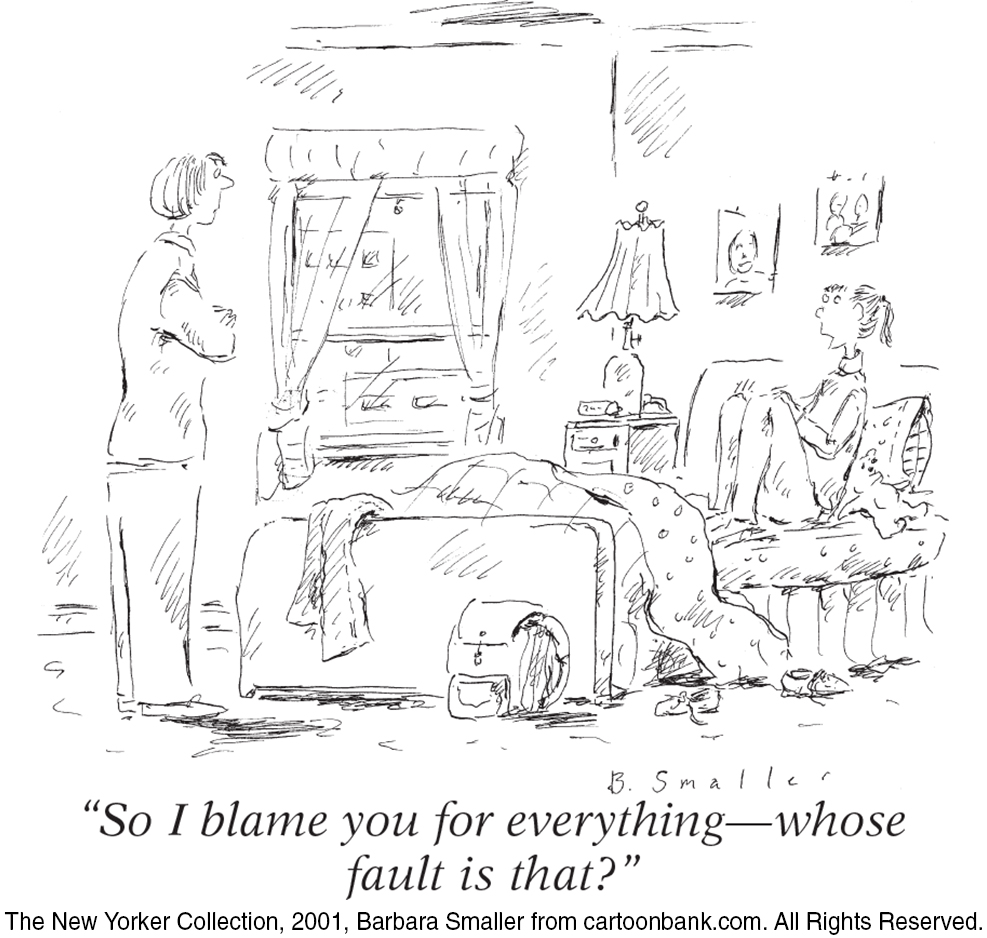

In procreation, a woman and a man shuffle their gene decks and deal a life-

But do parents really produce future adults with an inner wounded child by being (take your pick from the toxic-

Parents do matter. But parenting wields its largest effects at the extremes: the abused children who become abusive, the neglected who become neglectful, the loved but firmly handled who become self-

Yet in personality measures, shared environmental influences from the womb onward typically account for less than 10 percent of children’s differences. In the words of behavior geneticists Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels (1987; Plomin, 2011), “Two children in the same family are [apart from their shared genes] as different from one another as are pairs of children selected randomly from the population.” To developmental psychologist Sandra Scarr (1993), this implied that “parents should be given less credit for kids who turn out great and blamed less for kids who don’t.” Knowing children’s personalities are not easily sculpted by parental nurture, perhaps parents can relax a bit more and love their children for who they are.

For those who feel excluded by their peers, whether online or face-

Parent approval may matter in other ways. Teens have seen their parents as influential in shaping their religious faith and in thinking about college and career choices (Emerging Trends, 1997). A Gallup Youth Survey revealed that most shared their parents’ political views (Lyons, 2005).

Howard Gardner (1998) has concluded that parents and peers are complementary:

Parents are more important when it comes to education, discipline, responsibility, orderliness, charitableness, and ways of interacting with authority figures. Peers are more important for learning cooperation, for finding the road to popularity, for inventing styles of interaction among people of the same age. Youngsters may find their peers more interesting, but they will look to their parents when contemplating their own futures. Moreover, parents [often] choose the neighborhoods and schools that supply the peers.

This power to select a child’s neighborhood and schools gives parents an ability to influence the culture that shapes the child’s peer group. And because neighborhood influences matter, parents may want to become involved in intervention programs that aim at a whole school or neighborhood. If the vapors of a toxic climate are seeping into a child’s life, that climate—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the selection effect, and how might it affect a teen's decision to join sports teams at school?