13.1 Physical Development

13-

Like the declining daylight after the summer solstice, our physical abilities—

“I am still learning.”

Michelangelo, 1560, at age 85

Physical Changes in Middle Adulthood

Athletes over age 40 know all too well that physical decline gradually accelerates. During early and middle adulthood, physical vigor has less to do with age than with a person’s health and exercise habits. Many of today’s physically fit 50-

menopause the time of natural cessation of menstruation; also refers to the biological changes a woman experiences as her ability to reproduce declines.

Aging also brings a gradual decline in fertility, especially for women. For a 35-

With age, sexual activity lessens. Nevertheless, most men and women remain capable of satisfying sexual activity, and most express satisfaction with their sex life. This was true of 70 percent of Canadians surveyed (ages 40 to 64) and 75 percent of Finns (ages 65 to 74) (Kontula & Haavio-

Physical Changes in Late Adulthood

Is old age “more to be feared than death” (Juvenal, The Satires)? Or is life “most delightful when it is on the downward slope” (Seneca, Epistulae ad Lucilium)? What is it like to grow old?

SENSORY ABILITIES, STRENGTH, AND STAMINA Although physical decline begins in early adulthood, we are not usually acutely aware of it until later in life, when the stairs get steeper, the print gets smaller, and other people seem to mumble more. Muscle strength, reaction time, and stamina diminish in late adulthood. As a lifelong basketball player, I [DM] find myself increasingly not racing for that loose ball. But even diminished vigor is sufficient for normal activities.

“For some reason, possibly to save ink, the restaurants had started printing their menus in letters the height of bacteria.”

Dave Barry,

Dave Barry Turns Fifty, 1998

With age, visual sharpness diminishes, as does distance perception and adaptation to light-

The senses of smell and hearing also diminish. In Wales, teens’ loitering around a convenience store has been discouraged by a device that emits an aversive high-

Most stairway falls taken by older people occur on the top step, precisely where the person typically descends from a window-

HEALTH As people age, they care less about what their bodies look like and more about how their bodies function. For those growing older, there is both bad and good news about health. The bad news: The body’s disease-

THE AGING BRAIN Up to the teen years, we process information with greater and greater speed (Fry & Hale, 1996; Kail, 1991). But compared with teens and young adults, older people take a bit more time to react, to solve perceptual puzzles, even to remember names (Bashore et al., 1997; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997). The neural processing lag is greatest on complex tasks (Cerella, 1985; Poon, 1987). At video games, most 70-

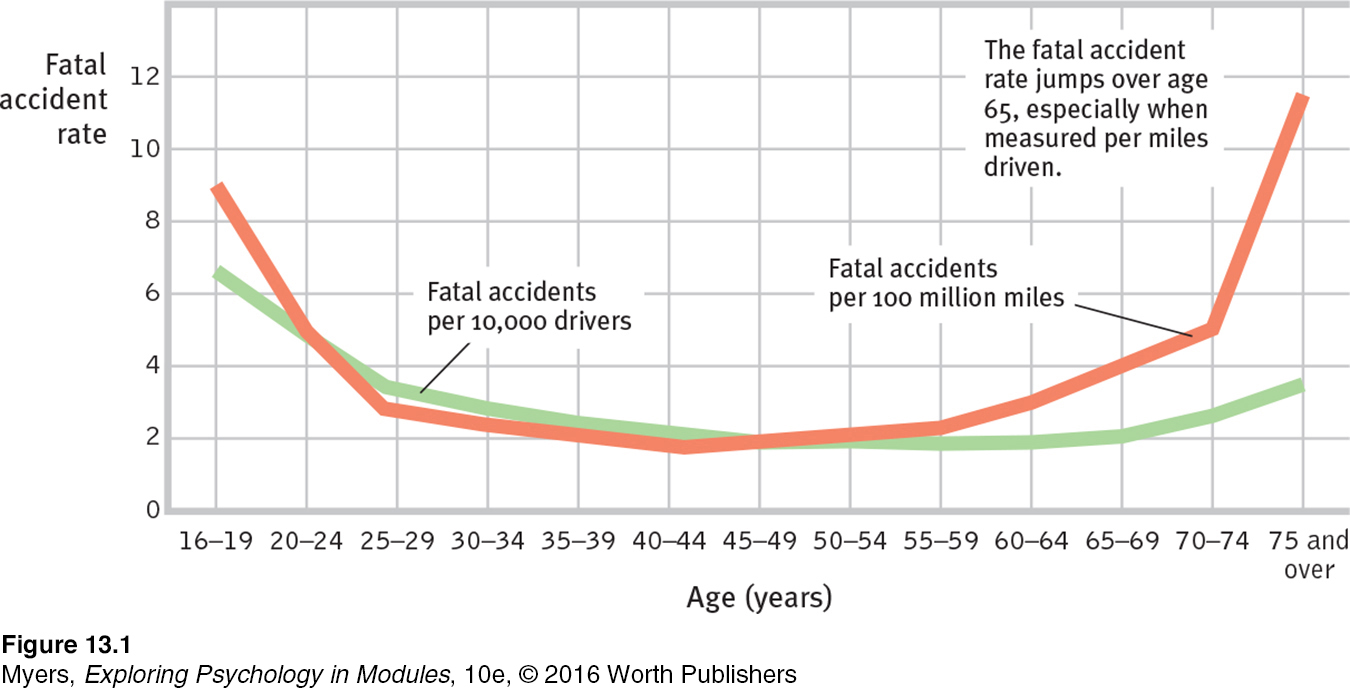

Slower neural processing combined with diminished sensory abilities can increase accident risks. As FIGURE 13.1 indicates, fatal accident rates per mile driven increase sharply after age 75. By age 85, they exceed the 16-

Brain regions important to memory begin to atrophy during aging (Fraser et al., 2015; Schacter, 1996). The blood-

EXERCISE AND AGING Exercise helps counteract some effects of aging. Physical exercise not only enhances muscles, bones, and energy and helps to prevent obesity and heart disease, it also stimulates brain cell development and neural connections, thanks perhaps to increased oxygen and nutrient flow (Erickson et al., 2013; Fleischman et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2007). Exercise aids memory by stimulating the development of neural connections and by promoting neurogenesis, the birth of new hippocampus nerve cells. And it increases the cellular mitochondria that help power both muscles and brain cells (Steiner et al., 2011).

Sedentary older adults randomly assigned to aerobic exercise programs exhibit enhanced memory, sharpened judgment, and reduced risk of significant cognitive decline (DeFina et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2010; Nagamatsu et al., 2013). Exercise also helps maintain the telomeres (Leslie, 2011). These tips of chromosomes wear down with age, much as the end of a shoelace frays. Telomere wear and tear is accelerated by smoking, obesity, and stress. Children who suffer frequent abuse or bullying exhibit shortened telomeres as biological scars (Shalev et al., 2013). As telomeres shorten, aging cells may die without being replaced by perfect genetic replicas (Epel, 2009).

The message is clear: We are more likely to rust from disuse than to wear out from overuse. Fit bodies support fit minds.