13.3 Social Development

13-

Many differences between younger and older adults are created by significant life events. A new job means new relationships, new expectations, and new demands. Marriage brings the joy of intimacy and the stress of merging two lives. The three years surrounding the birth of a child bring increased life satisfaction for most parents (Dyrdal & Lucas, 2011). The death of a loved one creates an irreplaceable loss. Do these adult life events shape a sequence of life changes?

Adulthood’s Ages and Stages

As people enter their forties, they undergo a transition to middle adulthood, a time when they realize that life will soon be mostly behind instead of ahead of them. Some psychologists have argued that for many the midlife transition is a crisis, a time of great struggle, regret, or even feeling struck down by life. The popular image of the midlife crisis is an early-

For the 1 in 4 adults who report experiencing a life crisis, the trigger is not age but a major event, such as illness, divorce, or job loss (Lachman, 2004). Some middle-

social clock the culturally preferred timing of social events such as marriage, parenthood, and retirement.

Life events trigger transitions to new life stages at varying ages. The social clock—the definition of “the right time” to leave home, get a job, marry, have children, or retire—

Even chance events can have lasting significance, by deflecting us down one road rather than another. Albert Bandura (1982, 2005) recalls the ironic true story of a book editor who came to one of Bandura’s lectures on the “Psychology of Chance Encounters and Life Paths”—and ended up marrying the woman who happened to sit next to him. The sequence that led to my [DM] authoring this book (which was not my idea) began with my being seated near, and getting to know, a distinguished colleague at an international conference. The road to my [ND] co-

“The important events of a person’s life are the products of chains of highly improbable occurrences.”

Joseph Traub, “Traub’s Law,” 2003

Adulthood’s Commitments

Two basic aspects of our lives dominate adulthood. Erik Erikson called them intimacy (forming close relationships) and generativity (being productive and supporting future generations). Sigmund Freud (1935/1960) put this more simply: The healthy adult, he said, is one who can love and work.

LOVE We typically flirt, fall in love, and commit—

Adult bonds of love are most satisfying and enduring when marked by a similarity of interests and values, a sharing of emotional and material support, and intimate self-

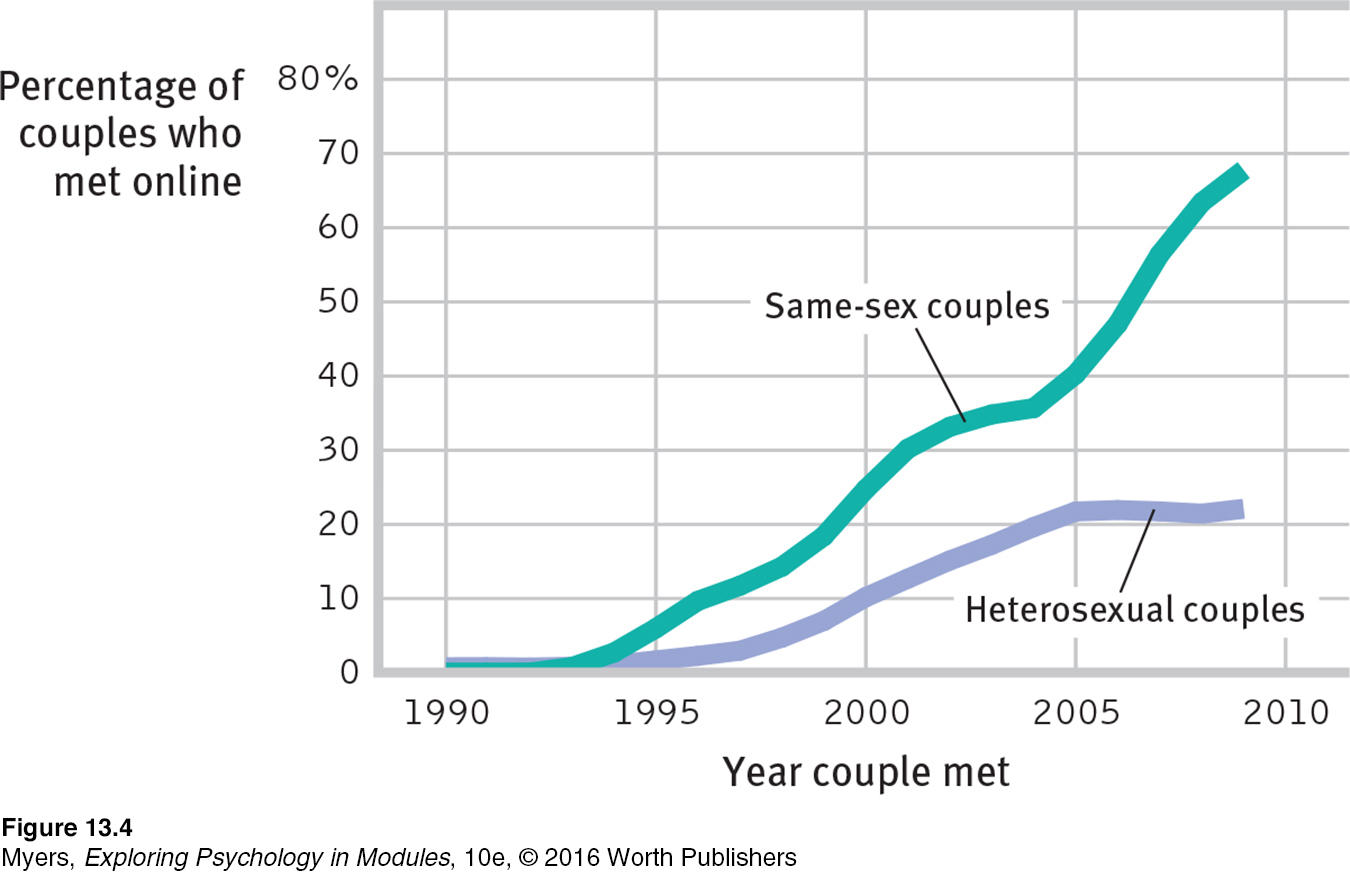

Historically, couples have met at school, on the job, through family, or, especially, through friends. Since the advent of the Internet, such matchmaking has been supplemented by a striking rise in couples who meet online—

Might test-

Although there is more variety in relationships today, the institution of marriage endures. Ninety-

What do you think? Does marriage correlate with happiness because marital support and intimacy breed happiness, because happy people more often marry and stay married, or both?

Relationships that last are not always devoid of conflict. Some couples fight but also shower each other with affection. Other couples never raise their voices yet also seldom praise each other or nuzzle. Both styles can last. After observing the interactions of 2000 couples, John Gottman (1994) reported one indicator of marital success: at least a five-

“Our love for children is so unlike any other human emotion. I fell in love with my babies so quickly and profoundly, almost completely independently of their particular qualities. And yet 20 years later I was (more or less) happy to see them go—

Developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik, “The Supreme Infant,” 2010

Often, love bears children. For most people, this most enduring of life changes is a happy event—

When children begin to absorb time, money, and emotional energy, satisfaction with the marriage itself may decline (Doss et al., 2009). This is especially likely among employed women who, more than they expected, may carry the traditional burden of doing the chores at home. Putting effort into creating an equitable relationship can thus pay double dividends: greater satisfaction, which breeds better parent-

“To understand your parents’ love, bear your own children.”

Chinese proverb

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To explore the connection between parenting and happiness, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To explore the connection between parenting and happiness, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?

Although love bears children, children eventually leave home. This departure is a significant and sometimes difficult event. For most people, however, an empty nest is a happy place (Adelmann et al., 1989; Gorchoff et al., 2008). Many parents experience a “postlaunch honeymoon,” especially if they maintain close relationships with their children (White & Edwards, 1990). As Daniel Gilbert (2006) has said, “The only known symptom of ‘empty nest syndrome’ is increased smiling.”

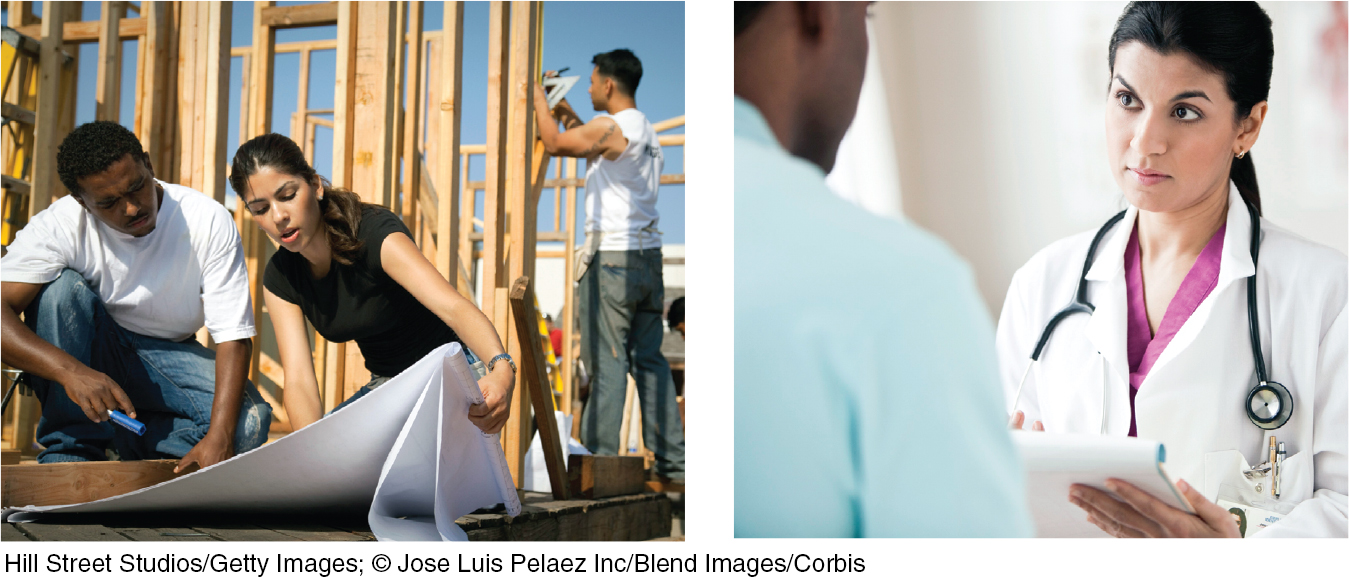

WORK For many adults, the answer to “Who are you?” depends a great deal on the answer to “What do you do?” For women and men, choosing a career path is difficult, especially during bad economic times. Even in the best of times, few students in their first two years of college or university can predict their later careers.

In the end, happiness is about having work that fits your interests and provides you with a sense of competence and accomplishment. It is having a close, supportive companion who cheers your accomplishments (Gable et al., 2006). And for some, it includes having children who love you and whom you love and feel proud of.

For more on work, including discovering your own strengths, see Appendix B: Psychology at Work.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Freud defined the healthy adult as one who is able to and to .

Well-Being Across the Life Span

13-

To live is to grow older. This moment marks the oldest you have ever been and the youngest you will henceforth be. That means we all can look back with satisfaction or regret, and forward with hope or dread. When asked what they would have done differently if they could relive their lives, people’s most common answer has been “taken my education more seriously and worked harder at it” (Kinnier & Metha, 1989; Roese & Summerville, 2005). Other regrets—

“When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced. Live your life in a manner so that when you die the world cries and you rejoice.”

Native American proverb

From the teens to midlife, people typically experience a strengthening sense of identity, confidence, and self-

Prior to the very end, however, Gallup researchers have discovered that the over-

“Still married after all these years?

No mystery.

We are each other’s habit,

And each other’s history.”

Judith Viorst,

“The Secret of Staying Married,” 2007

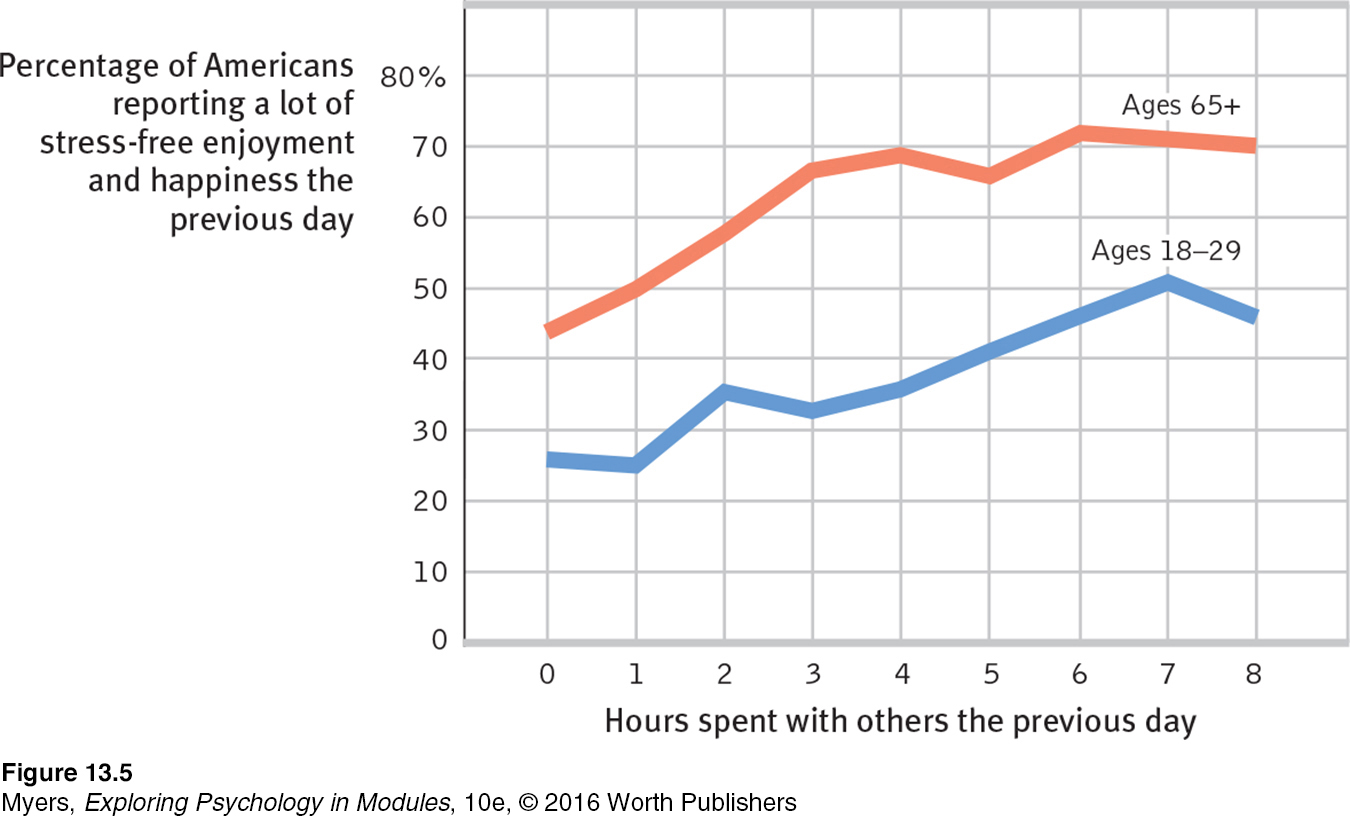

Compared with teens and young adults, older adults tend to have a smaller social network, with fewer friendships (Wrzus et al., 2012). Like people of all ages, older adults are, however, happiest when not alone (FIGURE 13.5). Older adults experience fewer problems in their relationships—

“At 20 we worry about what others think of us. At 40 we don’t care what others think of us. At 60 we discover they haven’t been thinking about us at all.”

Anonymous

The aging brain may help nurture these positive feelings. Brain scans of older adults show that the amygdala, a neural processing center for emotions, responds less actively to negative events (but not to positive events) (Mather et al., 2004). Brain-

“The best thing about being 100 is no peer pressure.”

Lewis W. Kuester, 2005,

on turning 100

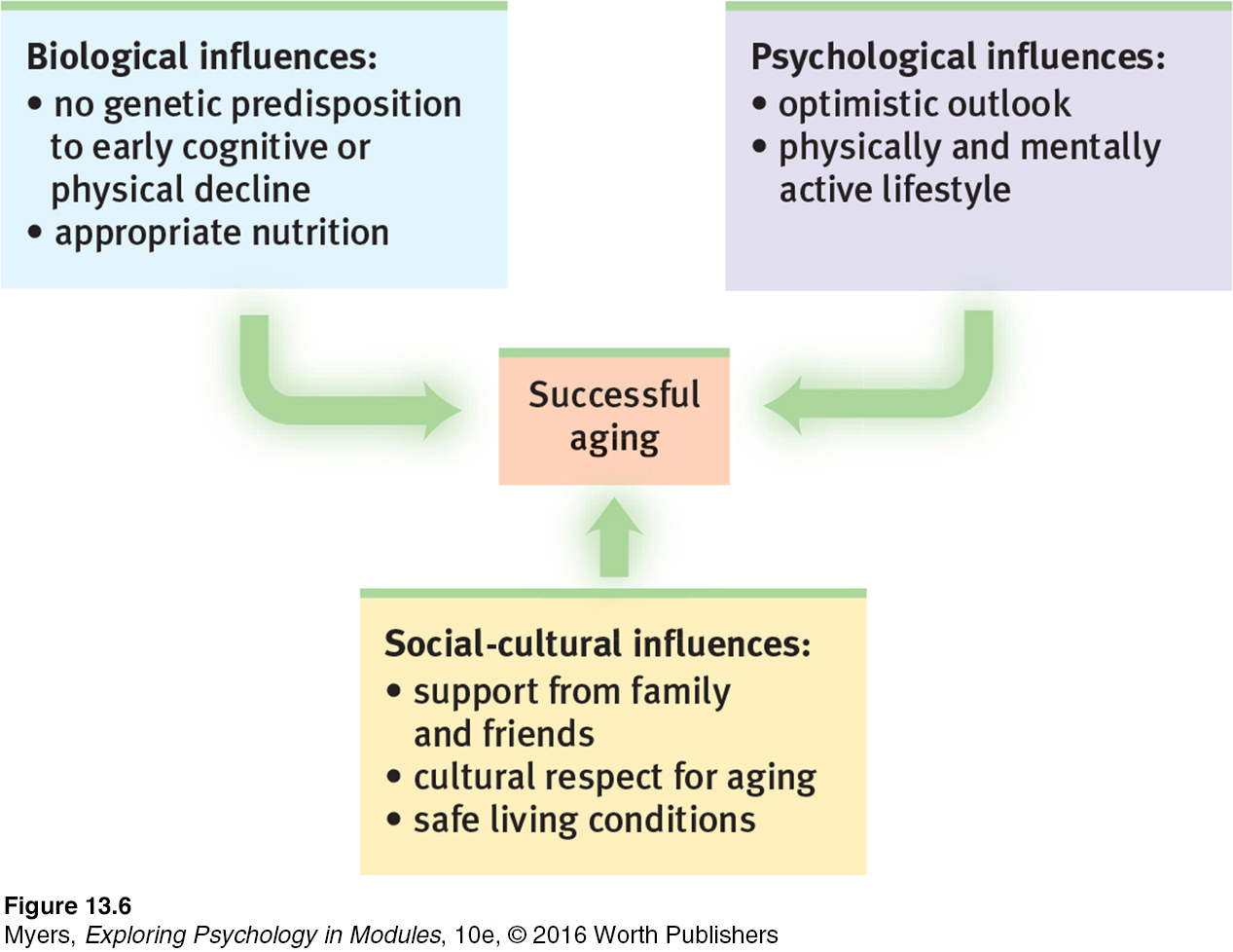

Moreover, at all ages, the bad feelings we associate with negative events fade faster than do the good feelings we associate with positive events (Walker et al., 2003). This leaves most older people with the comforting feeling that life, on balance, has been mostly good. Thanks to biological, psychological, and social-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are some of the most significant challenges and rewards of growing old?

Death and Dying

13-

Warning: If you begin reading the next paragraph, you will die.

But of course, if you hadn’t read this, you would still die in due time. “Time is a great teacher,” noted the nineteenth-

“Love—

Brian Moore,

The Luck of Ginger Coffey, 1960

Most of us will also suffer and cope with the deaths of relatives and friends. For most people, the most difficult separation they will experience is the death of a spouse—

For some, however, the loss is unbearable. One Danish long-

Even so, reactions to a loved one’s death range more widely than most suppose. Some cultures encourage public weeping and wailing; others hide grief. Within any culture, individuals differ. Given similar losses, some people grieve hard and long, others less so (Ott et al., 2007). Contrary to popular misconceptions, however:

terminally ill and bereaved people do not go through identical predictable stages, such as denial before anger (Friedman & James, 2008; Nolen-

Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). those who express the strongest grief immediately do not purge their grief more quickly (Bonanno & Kaltman, 1999; Wortman & Silver, 1989). However, grieving parents who try to protect their partner by “staying strong” and not discussing their child’s death may actually prolong the grieving (Stroebe et al., 2013).

bereavement therapy and self-

help groups offer support, but there is similar healing power in the passing of time, the support of friends, and the act of giving support and help to others (Baddeley & Singer, 2009; Brown et al., 2008; Neimeyer & Currier, 2009). Grieving spouses who talk often with others or receive grief counseling adjust about as well as those who grieve more privately (Bonanno, 2004; Stroebe et al., 2005).

“Consider, friend, as you pass by, as you are now, so once was I. As I am now, you too shall be. Prepare, therefore, to follow me.”

Scottish tombstone epitaph

Facing death with dignity and openness helps people complete the life cycle with a sense of life’s meaningfulness and unity—