10.1 Developmental Psychology’s Major Issues

10-

developmental psychology a branch of psychology that studies physical, cognitive, and social change throughout the life span.

Researchers find human development interesting for the same reasons most of the rest of us do—

Nature and nurture: How does our genetic inheritance (our nature) interact with our experiences (our nurture) to influence our development? How have your nature and your nurture influenced your life story?

Continuity and stages: What parts of development are gradual and continuous, like riding an escalator? What parts change abruptly in separate stages, like climbing rungs on a ladder?

Stability and change: Which of our traits persist through life? How do we change as we age?

“Nature is all that a man brings with him into the world; nurture is every influence that affects him after his birth.”

Francis Galton,

English Men of Science, 1874

Nature and Nurture

The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm helped form us, as individuals. Genes predispose both our shared humanity and our individual differences.

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Even differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. We are not formed by either nature or nurture, but by the interaction between them. Biological, psychological, and social-

Mindful of how others differ from us, however, we often fail to notice the similarities stemming from our shared biology. Regardless of our culture, we humans share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punishing and rejecting parents (Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991). Although ethnic groups have differed in some ways, including average school achievement, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well. Compared with the person-

Continuity and Stages

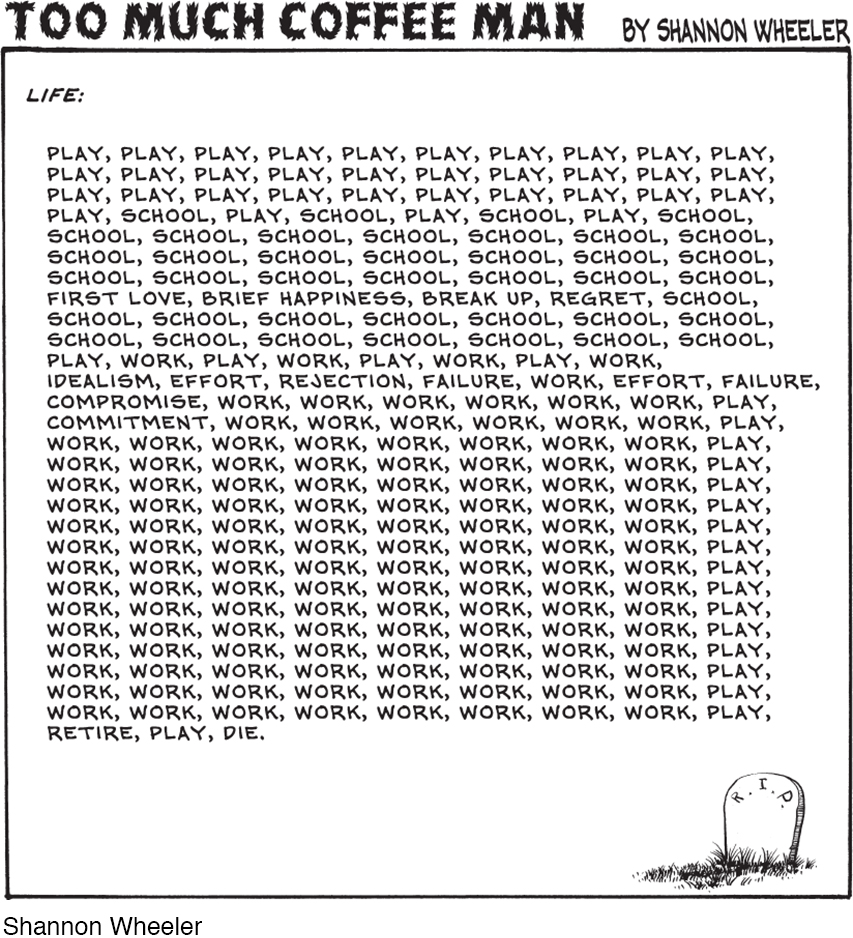

Do adults differ from infants as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—

Researchers who emphasize experience and learning typically see development as a slow, continuous shaping process. Those who emphasize biological maturation tend to see development as a sequence of genetically predisposed stages or steps: Although progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, everyone passes through the stages in the same order.

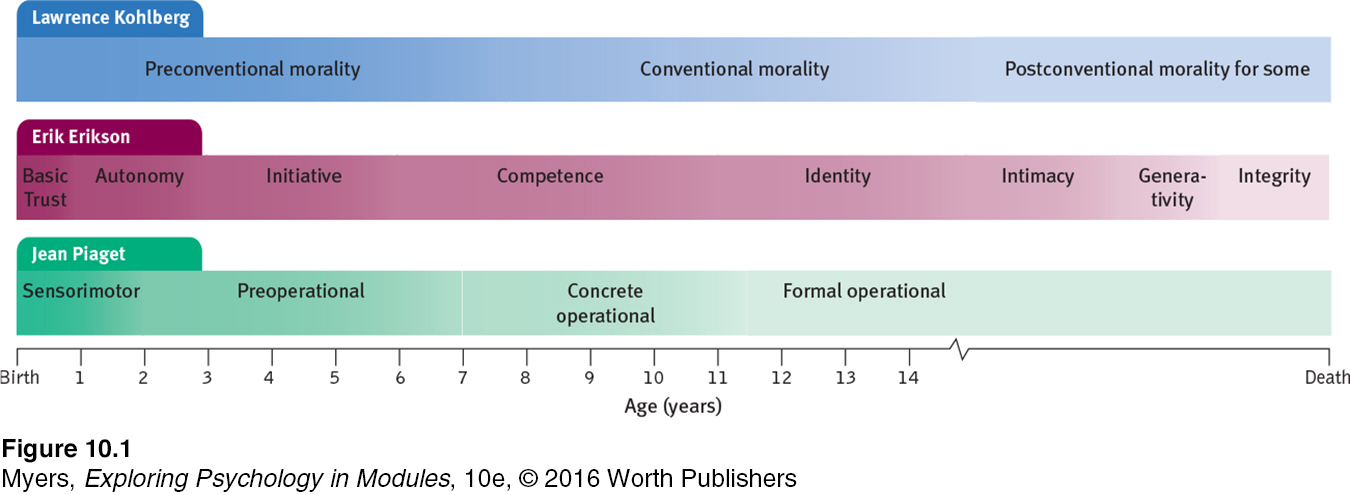

Are there clear-

Although many modern developmental psychologists do not identify as stage theorists, the stage concept remains useful. The human brain does experience growth spurts during childhood and puberty that correspond roughly to Piaget’s stages (Thatcher et al., 1987). And stage theories contribute a developmental perspective on the whole life span, by suggesting how people of one age think and act differently when they arrive at a later age.

Stability and Change

As we follow lives through time, do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-

Research reveals that we experience both stability and change. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament, are very stable:

One research team that studied 1000 people from ages 3 to 38 was struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Moffitt et al., 2013; Slutske et al., 2012). Out-

of- control 3- year- olds were the most likely to become teen smokers or adult criminals or out- of- control gamblers. Other studies have found that hyperactive, inattentive 5-

year- olds required more teacher effort at age 12 (Houts et al., 2010); that 6- year- old Canadian boys with conduct problems were four times more likely than other boys to be convicted of a violent crime by age 24 (Hodgins et al., 2013); and that extraversion among British 16- year- olds predicted their future happiness as 60- year- olds (Gale et al., 2013). Page 122Another research team interviewed adults who, 40 years earlier, had their talkativeness, impulsiveness, and humility rated by their elementary school teachers (Nave et al., 2010). To a striking extent, their traits persisted.

“At 70, I would say the advantage is that you take life more calmly. You know that ‘this, too, shall pass’!”

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1954

“As at 7, so at 70,” says a Jewish proverb. People predict that they will not change much in the future (Quoidbach et al., 2013). In some ways they are correct. The widest smilers in childhood and college photos are, years later, the ones most likely to enjoy enduring marriages (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

We cannot, however, predict all aspects of our future selves based on our early life. Our social attitudes, for example, are much less stable than our temperament (Moss & Susman, 1980). Older children and adolescents learn new ways of coping. Although delinquent children have elevated rates of later problems, many confused and troubled children blossom into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2013; Thomas & Chess, 1986). The struggles of the present may be laying a foundation for a happier tomorrow. Life is a process of becoming.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4, and most people become more conscientious, stable, agreeable, and self-

Life requires both stability and change. Stability provides our identity. It enables us to depend on others and be concerned about children’s healthy development. Our potential for change gives us our hope for a brighter future. It motivates our concerns about present influences and lets us adapt and grow with experience.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Developmental researchers who consider how biological, psychological, and social-

Question

Developmental researchers who emphasize learning and experience are supporting ; those who emphasize biological maturation are supporting .

Question

What findings in psychology support (1) the stage theory of development and (2) the idea of stability in personality across the life span? What findings challenge these ideas?