10.2 Prenatal Development and the Newborn

10-

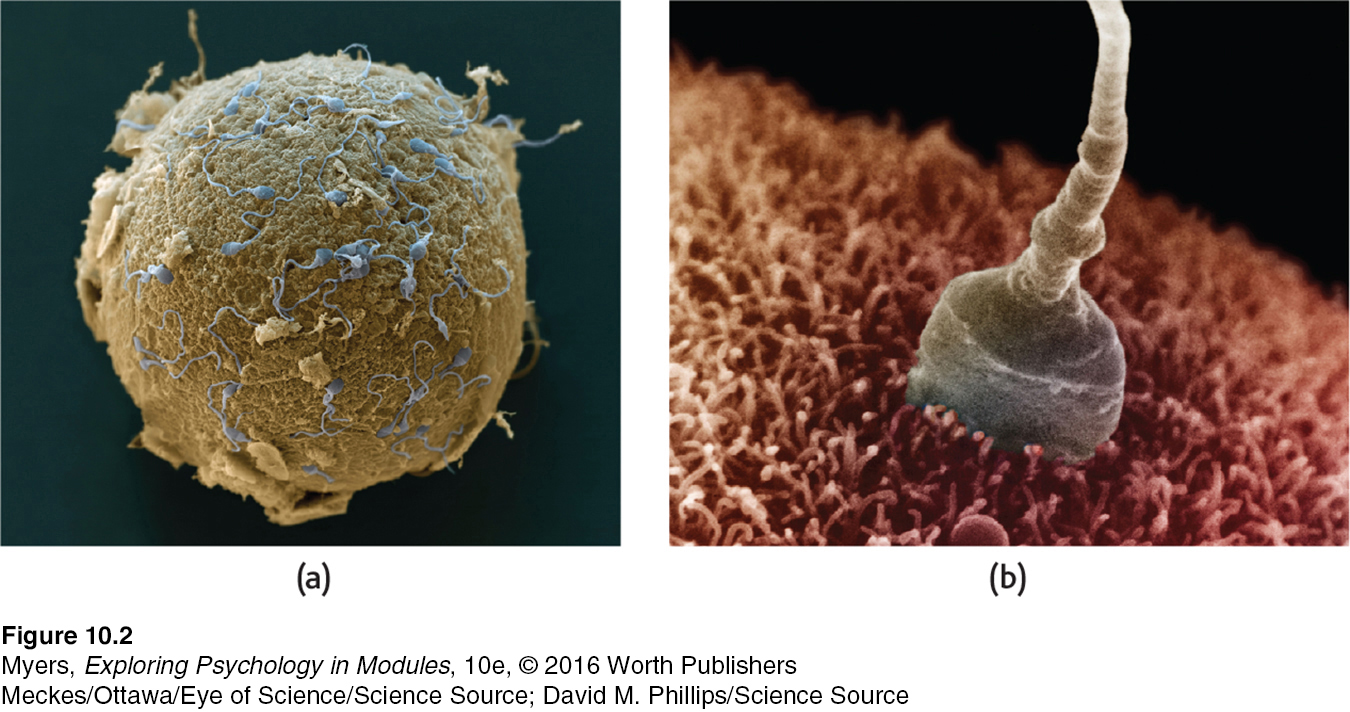

Conception

Nothing is more natural than a species reproducing itself. And nothing is more wondrous. For you, the process started inside your grandmother—

Some time after puberty, your mother’s ovary released a mature egg—

Consider it your most fortunate of moments. Among 250 million sperm, the one needed to make you, in combination with that one particular egg, won the race. And so it was for innumerable generations before us. If any one of our ancestors had been conceived with a different sperm or egg, or died before conceiving, or not chanced to meet their partner or. . . . The mind boggles at the improbable, unbroken chain of events that produced us.

Prenatal Development

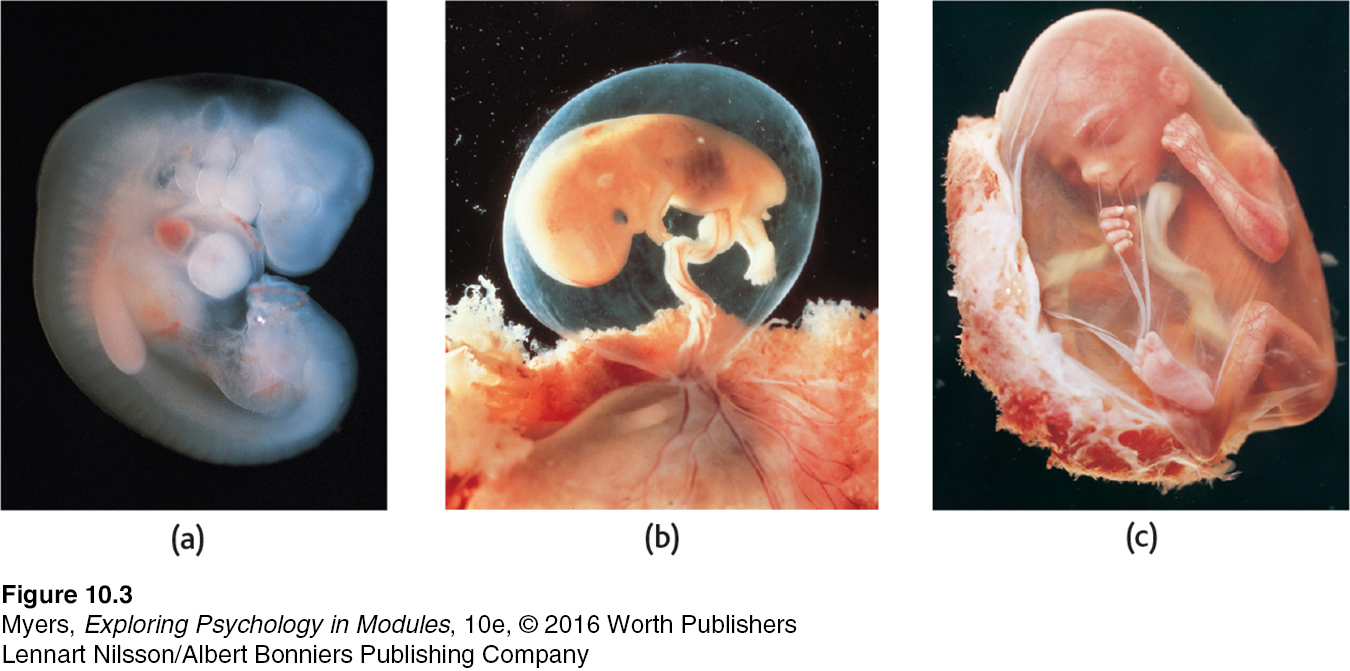

zygote the fertilized egg; it enters a 2-

How many fertilized eggs, called zygotes, survive beyond the first 2 weeks? Fewer than half (Grobstein, 1979; Hall, 2004). But for us, good fortune prevailed. One cell became 2, then 4—

Question

Care to guess your body's total number of cells?

embryo the developing human organism from about 2 weeks after fertilization through the second month.

About 10 days after conception, the zygote attaches to the mother’s uterine wall, beginning approximately 37 weeks of the closest human relationship. The zygote’s inner cells become the embryo (FIGURE 10.3a below). Many of its outer cells become the placenta, the life-

fetus the developing human organism from 9 weeks after conception to birth.

By 9 weeks after conception, an embryo looks unmistakably human (FIGURE 10.3b). It is now a fetus (Latin for “offspring” or “young one”). During the sixth month, organs such as the stomach have developed enough to give the fetus a good chance of survival if born prematurely.

At each prenatal stage, genetic and environmental factors affect our development. By the sixth month, microphone readings taken inside the uterus reveal that the fetus is responsive to sound and is exposed to the sound of its mother’s muffled voice (Ecklund-

They also prefer hearing their mother’s language. At about 30 hours old, American and Swedish newborns pause more in their pacifier sucking when listening to familiar vowels from their mother’s language (Moon et al., 2013). After repeatedly hearing a fake word (tatata) in the womb, Finnish newborns’ brain waves display recognition when hearing the word after birth (Partanen et al., 2014). If their mother spoke two languages during pregnancy, they display interest in both (Byers-

Prenatal development

Zygote: Conception to 2 weeks

Embryo: 2 to 9 weeks

Fetus: 9 weeks to birth

In the two months before birth, fetuses demonstrate learning in other ways, as when they adapt to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen (Dirix et al., 2009). Like people who adapt to the sound of trains in their neighborhood, fetuses get used to the honking. Moreover, four weeks later, they recall the sound (as evidenced by their blasé response, compared with the reactions of those not previously exposed).

“You shall conceive and bear a son. So then drink no wine or strong drink.”

Judges 13:7

teratogens (literally, “monster maker”) agents, such as chemicals and viruses, that can reach the embryo or fetus during prenatal development and cause harm.

Sounds are not the only stimuli fetuses are exposed to in the womb. In addition to transferring nutrients and oxygen from mother to fetus, the placenta screens out many harmful substances. But some slip by. Teratogens, agents such as viruses and drugs, can damage an embryo or fetus. This is one reason pregnant women are advised not to drink alcoholic beverages or smoke cigarettes. A pregnant woman never drinks or smokes alone. When alcohol enters her bloodstream and that of her fetus, it reduces activity in both their central nervous systems. Alcohol use during pregnancy may prime the woman’s offspring to like alcohol and may put them at risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder during their teen years. In experiments, when pregnant rats drank alcohol, their young offspring later displayed a liking for alcohol’s taste and odor (Youngentob et al., 2007, 2009).

fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) physical and cognitive abnormalities in children caused by a pregnant woman’s heavy drinking. In severe cases, signs include a small, out-

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. See also LaunchPad's 8-

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. See also LaunchPad's 8-

Even light drinking or occasional binge drinking can affect the fetal brain (Braun, 1996; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Marjonen et al., 2015; Sayal et al., 2009). Persistent heavy drinking puts the fetus at risk for a dangerously low birth weight, birth defects, and for future behavior problems, hyperactivity, and lower intelligence. For 1 in about 700 children, the effects are visible as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), marked by lifelong physical and mental abnormalities (May et al., 2014). The fetal damage may occur because alcohol has an epigenetic effect: It leaves chemical marks on DNA that switch genes abnormally on or off (Liu et al., 2009). Smoking during pregnancy also leaves epigenetic scars that weaken infants’ ability to handle stress (Stroud et al., 2014).

If a pregnant woman experiences extreme stress, the stress hormones flooding her body may indicate a survival threat to the fetus and produce an earlier delivery (Glynn & Sandman, 2011). Some stress in early life prepares us to cope with later adversity in life. But substantial prenatal stress exposure puts a child at increased risk for health problems such as hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and psychiatric disorders.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The first two weeks of prenatal development is the period of the . The period of the lasts from 9 weeks after conception until birth. The time between those two prenatal periods is considered the period of the .

The Competent Newborn

10-

“I felt like a man trapped in a woman’s body. Then I was born.”

Comedian Chris Bliss

Babies come with software preloaded on their neural hard drives. Having survived prenatal hazards, we as newborns came equipped with automatic reflex responses ideally suited for our survival. We withdrew our limbs to escape pain. If a cloth over our face interfered with our breathing, we turned our head from side to side and swiped at it.

New parents are often in awe of the coordinated sequence of reflexes by which their baby gets food. When something touches their cheek, babies turn toward that touch, open their mouth, and vigorously root for a nipple. Finding one, they automatically close on it and begin sucking—

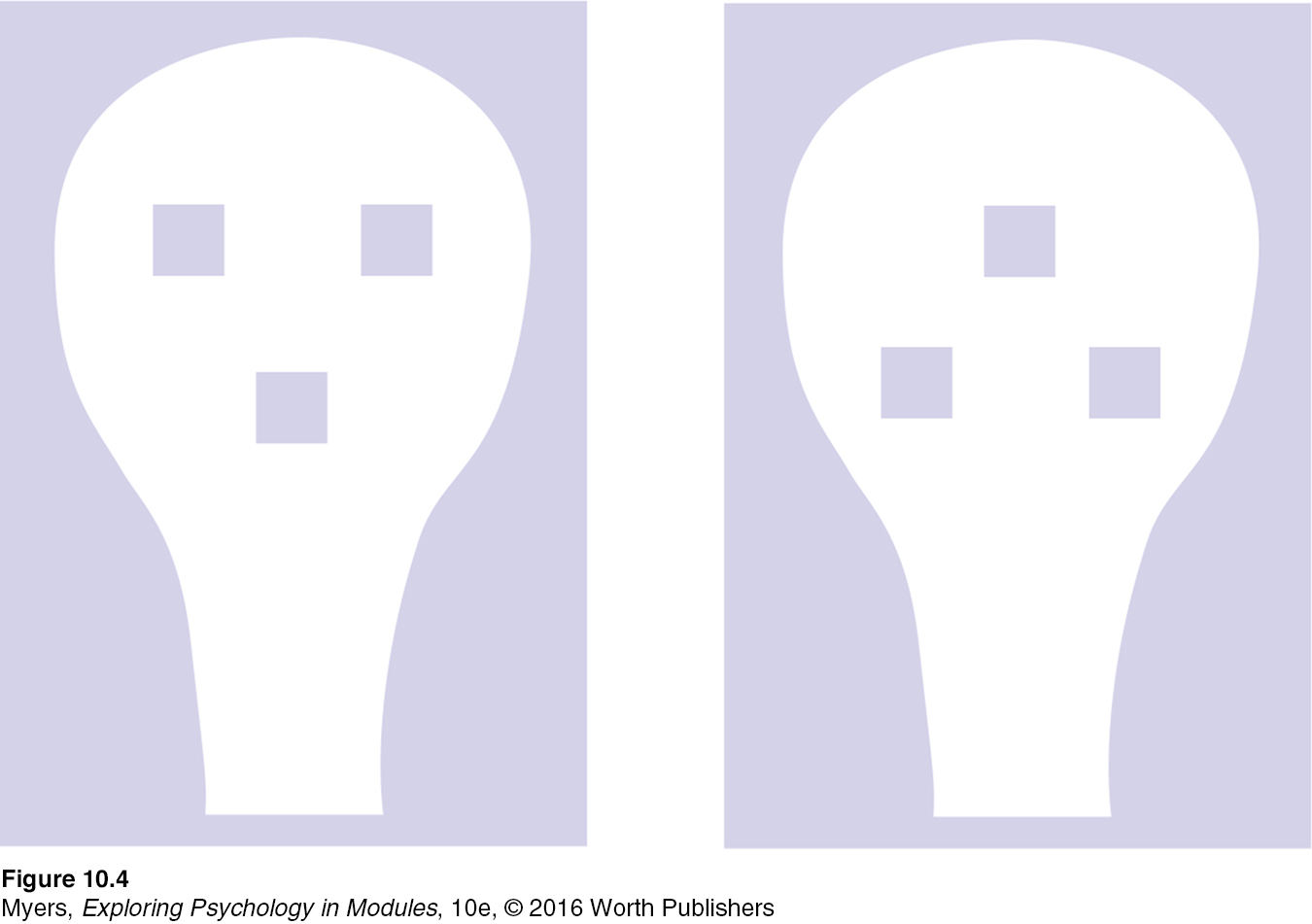

The pioneering American psychologist William James presumed that newborns experience a “blooming, buzzing confusion,” an assumption few people challenged until the 1960s. Then scientists discovered that babies can tell you a lot—

habituation decreasing responsiveness with repeated stimulation. As infants gain familiarity with repeated exposure to a stimulus, their interest wanes and they look away sooner.

Consider how researchers exploit habituation—decreased responding with repeated stimulation. We saw this earlier when fetuses adapted to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen. The novel stimulus gets attention when first presented. With repetition, the response weakens. This seeming boredom with familiar stimuli gives us a way to ask infants what they see and remember.

Even as newborns, we prefer sights and sounds that facilitate social responsiveness. We turn our heads in the direction of human voices. We gaze longer at a drawing of a face-

Within days after birth, our brain’s neural networks were stamped with the smell of our mother’s body. Week-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Developmental psychologists use repeated stimulation to test an infant's to a stimulus.