14.1 How Are We Alike? How Do We Differ?

14-

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are unisex—

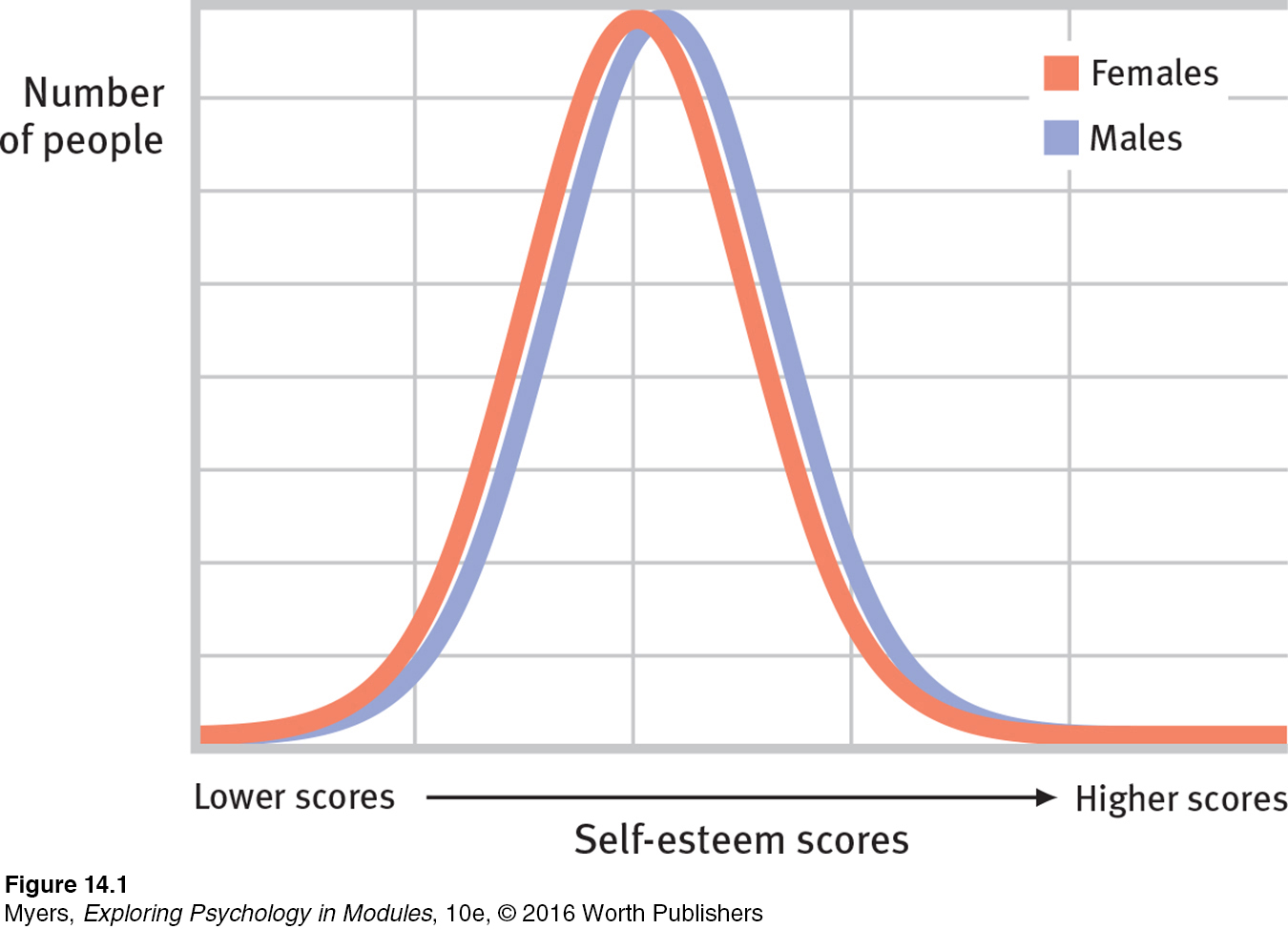

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much-

Gender differences appear throughout this book, but for now let’s take a closer look at three areas—

Aggression

aggression any physical or verbal behavior intended to harm someone physically or emotionally.

To a psychologist, aggression is any physical or verbal behavior intended to hurt someone physically or emotionally. Think of some aggressive people you have heard about. Are most of them men? Men generally admit to more aggression. They also commit more extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal—

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated gender differences in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). And outside the laboratory, men—

relational aggression an act of aggression (physical or verbal) intended to harm a person’s relationship or social standing.

Here’s another question: Think of examples of people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2007, 2009).

Social Power

Imagine you’ve walked into a job interview and are taking your first look at the two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-

Which interviewer is male?

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Schwartz & Rubel-

When groups form, whether as juries or companies, leadership tends to go to males (Colarelli et al., 2006). And when salaries are paid, those in traditionally male occupations receive more.

When people run for election, women who appear hungry for political power experience less success than their equally power-

hungry male counterparts (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010). And when elected, political leaders usually are men, who held 78 percent of the seats in the world’s governing parliaments in 2015 (IPU, 2015).

Men and women also lead differently. Men tend to be more directive, telling people what they want and how to achieve it. Women tend to be more democratic, more welcoming of others’ input in decision making (Eagly & Carli, 2007; van Engen & Willemsen, 2004). When interacting, men have been more likely to offer opinions, women to express support (Aries, 1987; Wood, 1987). In everyday behavior, men tend to act as powerful people often do: talking assertively, interrupting, initiating touches, and staring. And they smile and apologize less (Leaper & Ayres, 2007; Major et al., 1990; Schumann & Ross, 2010). Such behaviors help sustain men’s greater social power.

Women’s 2015 representation in national parliaments ranged from 13 percent in the Pacific region to 41 percent in Scandinavia (IPU, 2015).

Social Connectedness

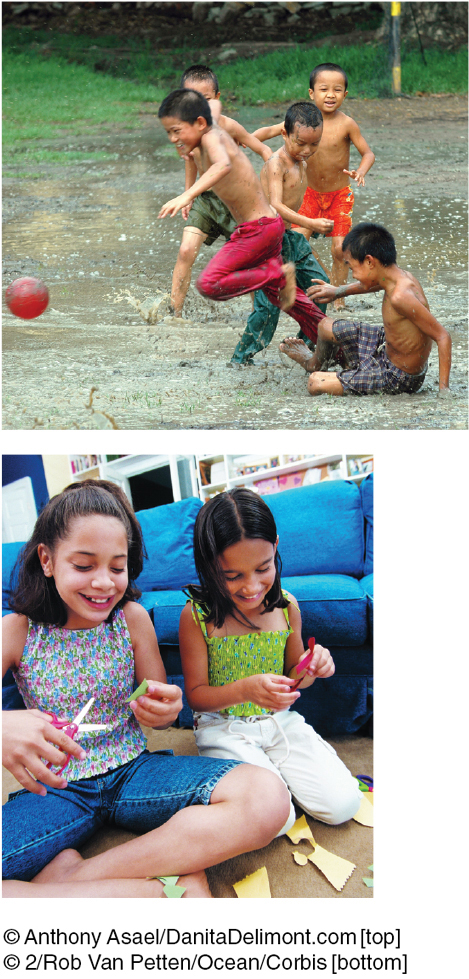

Whether male or female, we all have a need to belong, though we may satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Even as children, males typically form large play groups. Boys’ games brim with activity and competition, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As adults, men enjoy doing activities side by side, and they tend to use conversation to communicate solutions (Tannen, 1990; Wright, 1989).

Females tend to be more interdependent. In childhood, girls usually play in small groups, often with one friend. They compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991). Teen girls spend more time with friends and less time alone (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). In late adolescence, they spend more time on social networking sites (Pryor et al., 2007, 2011), and teen girls average twice as many text messages per day as boys (Lenhart, 2012). As adults, women take more pleasure in talking face to face, and they tend to use conversation more to explore relationships. Brain scans suggest that women’s brains are better wired to improve social relationships, and men’s brains to connect perception with action (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013).

A gender difference in communication style was apparent in one New Zealand study of student e-

More than a half-

In the workplace, women are less often driven by money and status, and more often opt for reduced work hours (Pinker, 2008). For many, family obligations loom large, with mothers, compared to fathers, spending twice as many hours doing child care (Parker & Wang, 2013). Both men and women have reported their friendships with women as more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Kuttler et al., 1999; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988). When searching for understanding from someone who will share their worries and hurts, people usually turn to women. How do they cope with their own stress? Compared with men, women are more likely to turn to others for support. They are said to tend and befriend (Tamres et al., 2002; Taylor, 2002).

The gender gap in both social connectedness and power peaks in late adolescence and early adulthood—

So, although women and men are more alike than different, there are some behavior differences between the average woman and man. Are such differences dictated by our biology? Shaped by our cultures and other experiences? Do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Read on.

“In the long years liker must they grow; The man be more of woman, she of man.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Princess, 1847

RETRIEVE IT

Question

________ (Men/Women) are more likely to commit relational aggression, and ________(men/women) are more likely to commit physical aggression.

Question

________(Men/Women) have tended to express more personal and professional interest in people and less interest in things.