17.1 Light Energy and Eye Structures

17-

Our eyes receive light energy and transduce (transform) it into neural messages that our brain then processes into what we consciously see. How does such a taken-

The Stimulus Input: Light Energy

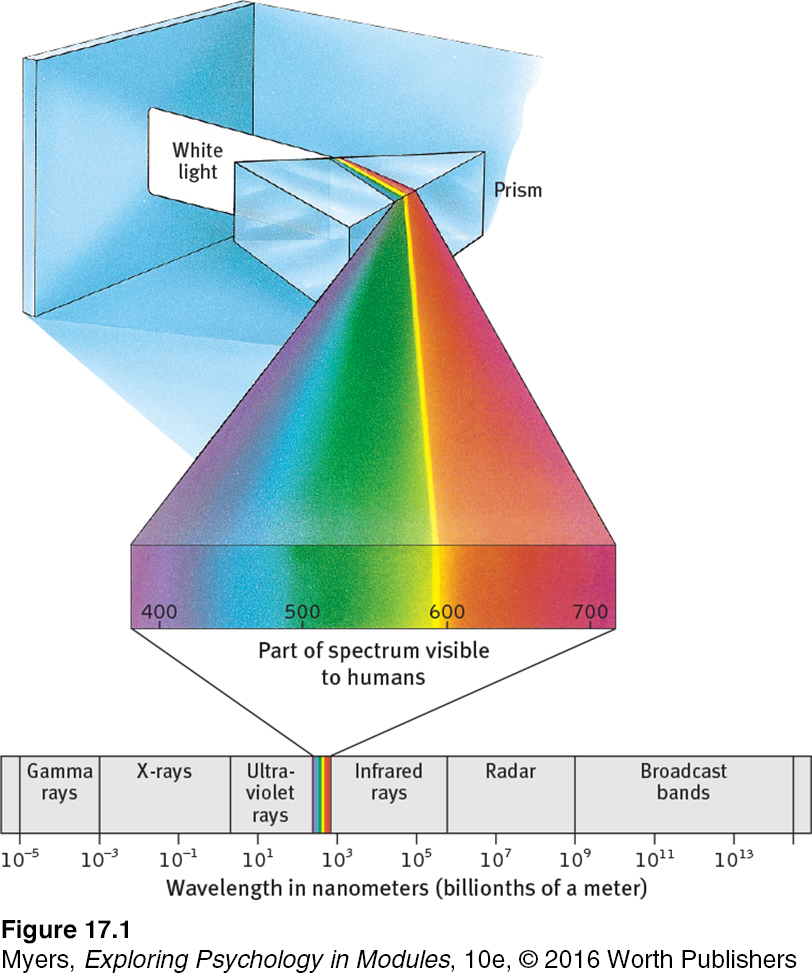

When you look at a bright red tulip, the stimuli striking your eyes are not particles of the color red but pulses of electromagnetic energy that your visual system perceives as red. What we see as visible light is but a thin slice of the whole spectrum of electromagnetic energy, ranging from imperceptibly short gamma waves to the long waves of radio transmission (FIGURE 17.1 below). Other organisms are sensitive to differing portions of the spectrum. Bees, for instance, cannot see what we perceive as red but can see ultraviolet light.

wavelength the distance from the peak of one light wave or sound wave to the peak of the next. Electromagnetic wavelengths vary from the short blips of cosmic rays to the long pulses of radio transmission.

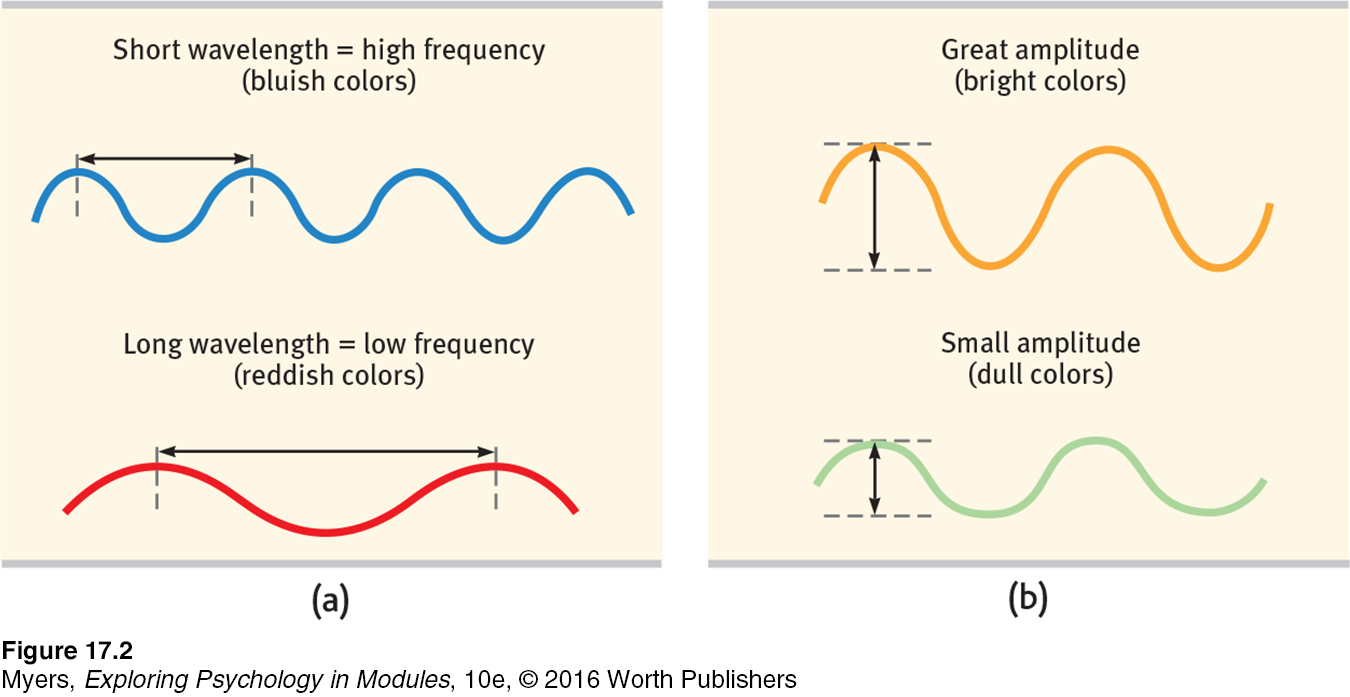

hue the dimension of color that is determined by the wavelength of light; what we know as the color names blue, green, and so forth.

intensity the amount of energy in a light wave or sound wave, which influences what we perceive as brightness or loudness. Intensity is determined by the wave’s amplitude (height).

Two physical characteristics of light help determine our experience. Light’s wavelength—the distance from one wave peak to the next (FIGURE 17.2a below)—determines its hue (the color we experience, such as a tulip’s red petals or green leaves). Intensity—the amount of energy in light waves (determined by a wave’s amplitude, or height)—influences brightness (FIGURE 17.2b). To understand how we transform physical energy into color and meaning, consider the eye.

The Eye

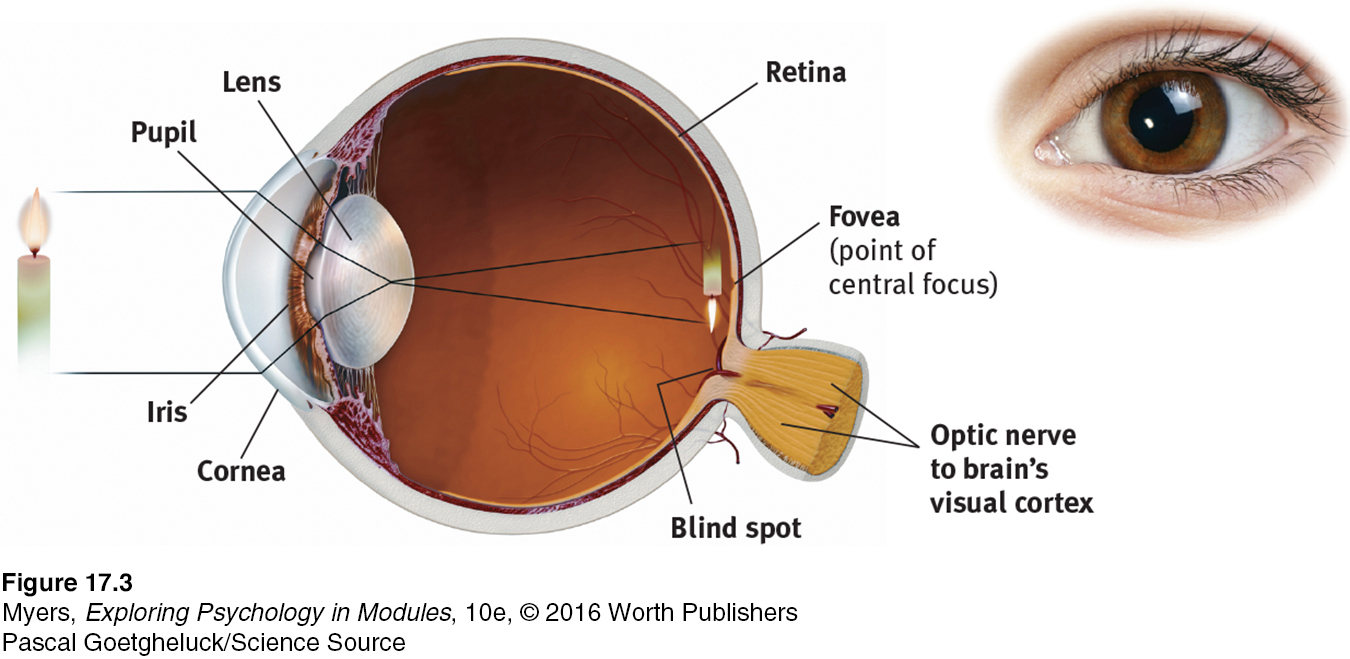

Light enters the eye through the cornea, which bends light to help provide focus (FIGURE 17.3 below). The light then passes through the pupil, a small adjustable opening surrounded by the iris, a colored muscle that controls the size of the pupil by dilating or constricting in response to light intensity—

retina the light-

accommodation the process by which the eye’s lens changes shape to focus near or far objects on the retina.

Behind the pupil is a transparent lens that focuses incoming light rays into an image on the retina, a multilayered tissue on the eyeball’s sensitive inner surface. The lens focuses the rays by changing its curvature and thickness, in a process called accommodation.

For centuries, scientists knew that when an image of a candle passes through a small opening, it casts an inverted mirror image on a dark wall behind. If the image passing through the pupil casts this sort of upside-