16.4 Sensory Adaptation

16-

sensory adaptation diminished sensitivity as a consequence of constant stimulation.

Entering your neighbors’ living room, you smell a musty odor. You wonder how they endure it, but within minutes you no longer notice it. Sensory adaptation has come to your rescue. When we are constantly exposed to an unchanging stimulus, we typically become less aware of it because our nerve cells fire less frequently. (To experience sensory adaptation, move your watch up your wrist an inch. You will feel it—

“We need above all to know about changes; no one wants or needs to be reminded 16 hours a day that his shoes are on.”

Neuroscientist David Hubel (1979)

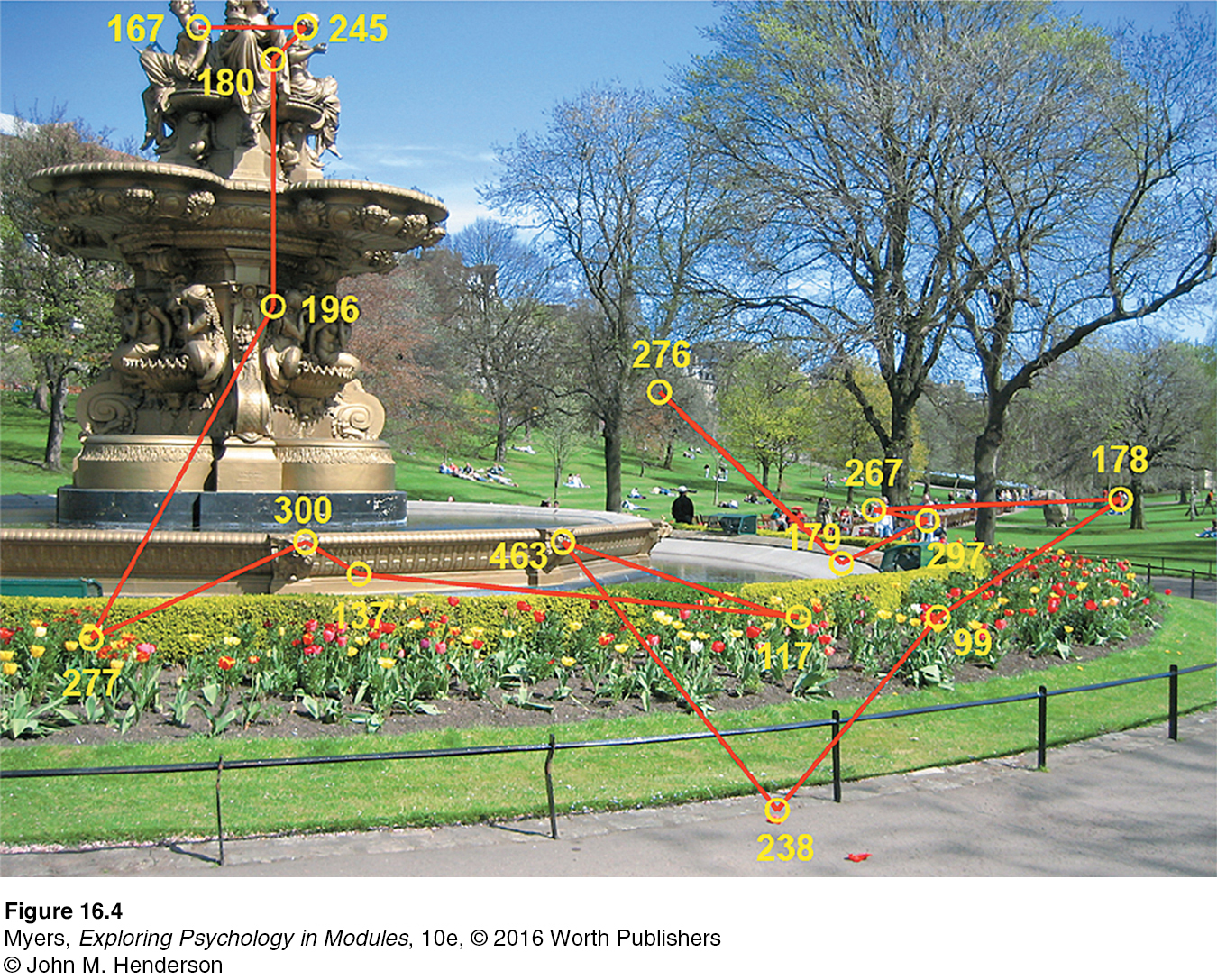

Why, then, if we stare at an object without flinching, does it not vanish from sight? Because, unnoticed by us, our eyes are always moving (FIGURE 16.4). This continual flitting from one spot to another ensures that stimulation on the eyes’ receptors continually changes.

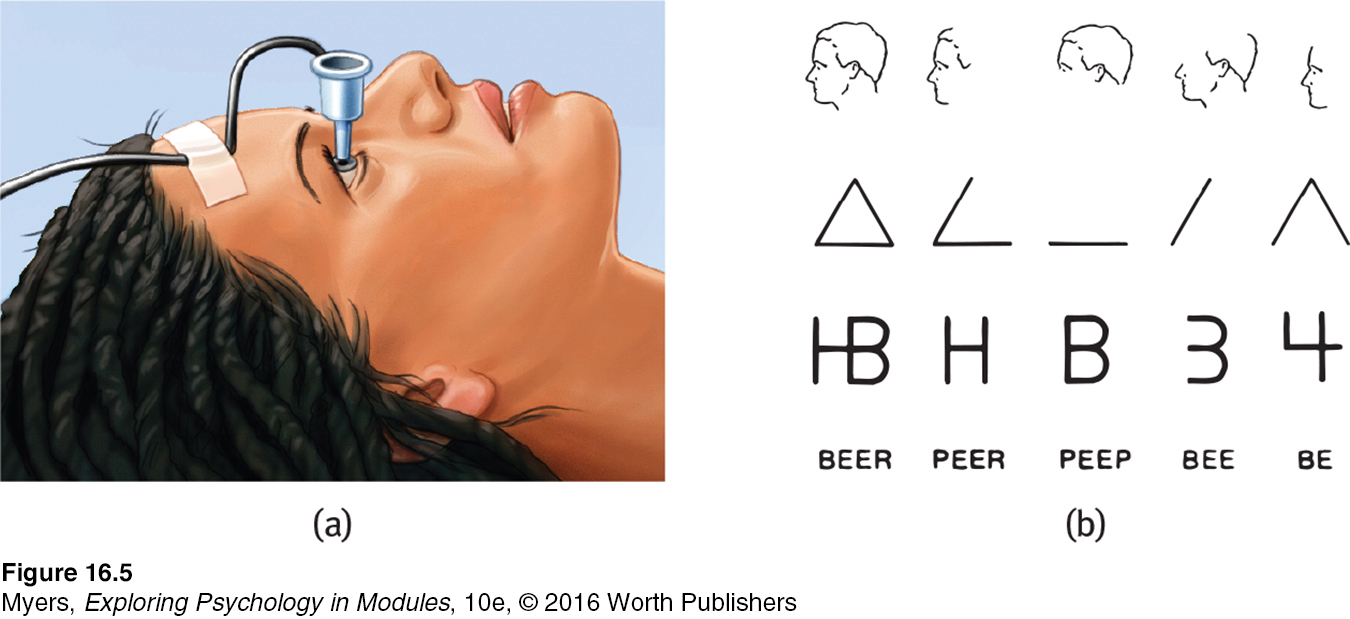

What if we actually could stop our eyes from moving? Would sights seem to vanish, as odors do? To find out, psychologists have devised ingenious instruments that maintain a constant image on the eye’s inner surface. Imagine that we have fitted a volunteer, Mary, with one of these instruments—

If we project images through this instrument, what will Mary see? At first, she will see the complete image. But within a few seconds, as her sensory system begins to fatigue, things get weird. Bit by bit, the image vanishes, only to reappear and then disappear—

Although sensory adaptation reduces our sensitivity to constant stimulation, it offers an important benefit: freedom to focus on informative changes in our environment without being distracted by background chatter. Stinky or heavily perfumed people don’t notice their odor because, like you and me, they adapt to what’s constant and detect only change. Our sensory receptors are alert to novelty; bore them with repetition and they free our attention for more important things. The point to remember: We perceive the world not exactly as it is, but as it is useful for us to perceive it.

Our sensitivity to changing stimulation helps explain television’s attention-

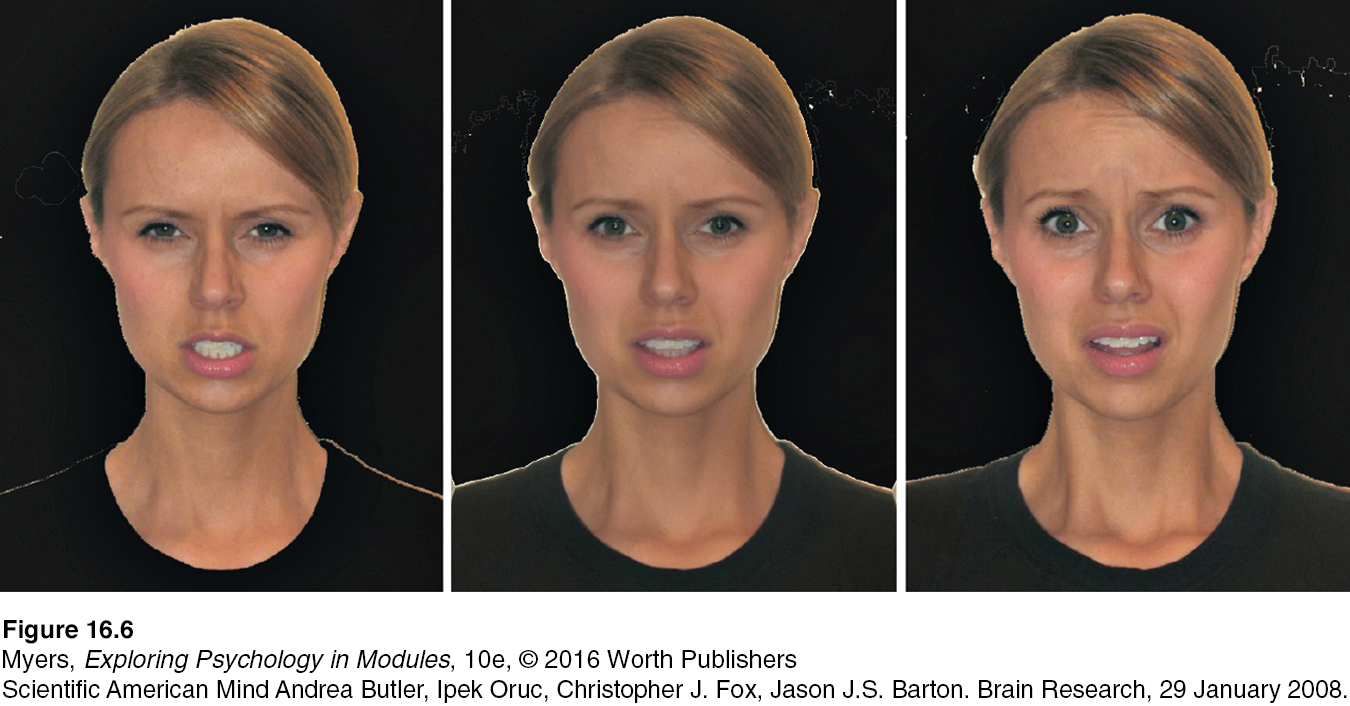

Sensory adaptation even influences how we perceive emotions. By creating a 50-

Sensory adaptation and sensory thresholds are important ingredients in our perceptions of the world around us. Much of what we perceive comes not just from what’s “out there,” but also from what’s behind our eyes and between our ears.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why is it that after wearing shoes for a while, you cease to notice them (until questions like this draw your attention back to them)?