24.2 Memory Construction Errors

24-

reconsolidation a process in which previously stored memories, when retrieved, are potentially altered before being stored again.

Memory is not precise. Like scientists who infer a dinosaur’s appearance from its remains, we infer our past from stored information plus what we later imagined, expected, saw, and heard. We don’t just retrieve memories, we reweave them. Like Wikipedia pages, memories can be continuously revised. When we “replay” a memory, we often replace the original with a slightly modified version (Hardt et al., 2010). (Memory researchers call this reconsolidation.) So, in a sense, said Joseph LeDoux (2009), “your memory is only as good as your last memory. The fewer times you use it, the more pristine it is.” This means that, to some degree, “all memory is false” (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009b).

Despite knowing all this, I [DM] recently rewrote my own past. It happened at an international conference, where memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus (2012) was demonstrating how memory works. Loftus showed us a handful of individual faces that we were later to identify, as if in a police lineup. Then, she showed us some pairs of faces, one face we had seen earlier and one we had not, and asked us to identify the one we had seen. But one pair she had slipped in included two new faces, one of which was rather like a face we had seen earlier. Most of us understandably but wrongly identified this face as one we had previously seen. To climax the demonstration, when she showed us the originally seen face and the previously chosen wrong face, most of us picked the wrong face! As a result of our memory reconsolidation, we—

Clinical researchers have experimented with people’s memory reconsolidation. They had people recall a traumatic or negative experience, then disrupt the reconsolidation of that memory with a drug or brief, painless electroconvulsive shock (Kroes et al., 2014; Lonergan, 2013). If, indeed, it becomes possible to erase your memory for a specific traumatic experience—

Misinformation and Imagination Effects

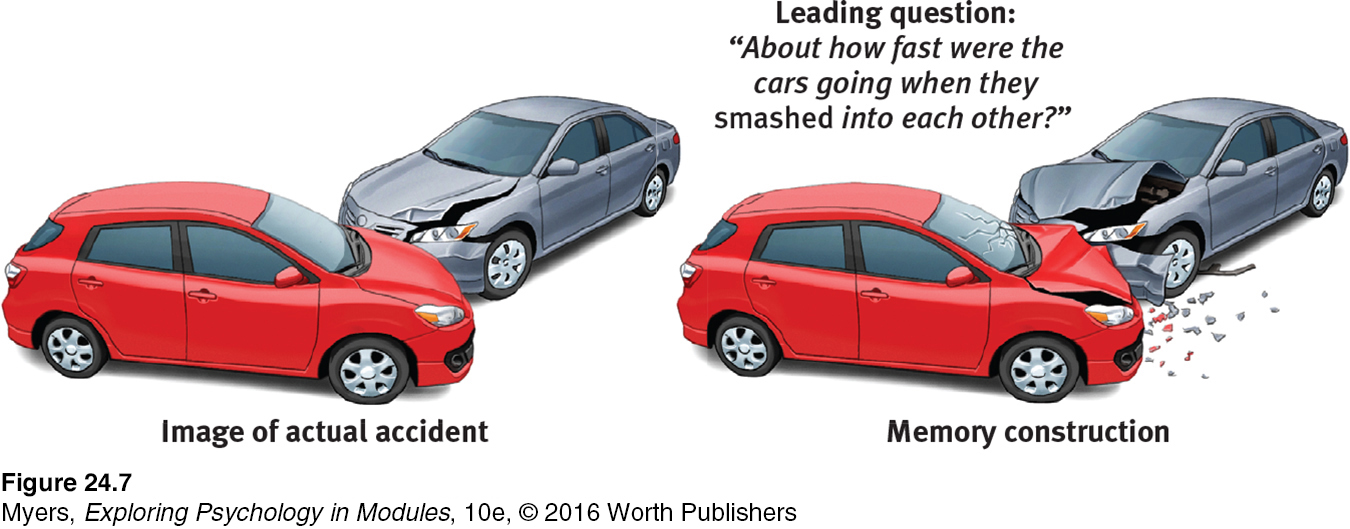

In more than 200 experiments involving more than 20,000 people, Loftus has shown how eyewitnesses reconstruct their memories after a crime or an accident. In one experiment, two groups of people watched a film clip of a traffic accident and then answered questions about what they had seen (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). Those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” gave higher speed estimates than those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” A week later, when asked whether they recalled seeing any broken glass, people who had heard smashed were more than twice as likely to report seeing glass fragments (FIGURE 24.7). In fact, the film showed no broken glass.

misinformation effect when misleading information has corrupted one’s memory of an event.

In many follow-

“Memory is insubstantial. Things keep replacing it. Your batch of snapshots will both fix and ruin your memory. . . . You can’t remember anything from your trip except the wretched collection of snapshots.”

Annie Dillard, “To Fashion a Text,” 1988

So powerful is the misinformation effect that it can influence later attitudes and behaviors (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009a). One experiment falsely suggested to some Dutch university students that, as children, they became ill after eating spoiled egg salad (Geraerts et al., 2008). After absorbing that suggestion, they were less likely to eat egg-

Digitally altered photos have also produced this imagination inflation. In experiments, researchers have altered photos from a family album to show some family members taking a hot-

In the discussion of mnemonics, we gave you six words and told you we would quiz you about them later. How many of these words can you now recall? Of these, how many are high-

In British and Canadian university surveys, nearly one-

“It isn’t so astonishing, the number of things I can remember, as the number of things I can remember that aren’t so.”

Author Mark Twain (1835–

Source Amnesia

source amnesia attributing to the wrong source an event we have experienced, heard about, read about, or imagined. (Also called source misattribution.) Source amnesia, along with the misinformation effect, is at the heart of many false memories.

Among the frailest parts of a memory is its source. We may recognize someone but have no idea where we have seen the person. We may dream an event and later be unsure whether it really happened. We may misrecall how we learned about something (Henkel et al., 2000). Psychologists are not immune to this process. Famed child psychologist Jean Piaget was startled as an adult to learn that a vivid, detailed memory from his childhood—

Debra Poole and Stephen Lindsay (1995, 2001, 2002) demonstrated source amnesia among preschoolers. They had the children interact with “Mr. Science,” who engaged them in activities such as blowing up a balloon with baking soda and vinegar. Three months later, on three successive days, their parents read them a story describing some things the children had experienced with Mr. Science and some they had not. When a new interviewer asked what Mr. Science had done with them—

Because the misinformation effect and source amnesia happen outside our awareness, it is nearly impossible to sift suggested ideas out of the larger pool of real memories (Schooler et al., 1986). Perhaps you can recall describing a childhood experience to a friend and filling in memory gaps with reasonable guesses and assumptions. We all do it, and after more retellings, those guessed details—

déjà vu that eerie sense that “I’ve experienced this before.” Cues from the current situation may unconsciously trigger retrieval of an earlier experience.

Source amnesia also helps explain déjà vu (French for “already seen”). Two-

“Do you ever get that strange feeling of vujà dé? Not déjà vu; vujà dé. It’s the distinct sense that, somehow, something just happened that has never happened before. Nothing seems familiar. And then suddenly the feeling is gone. Vujà dé.”

Comedian George Carlin (1937–

The key to déjà vu seems to be familiarity with a stimulus without a clear idea of where we encountered it before (Cleary, 2008). Normally, we experience a feeling of familiarity (thanks to temporal lobe processing) before we consciously remember details (thanks to hippocampus and frontal lobe processing). When these functions (and brain regions) are out of sync, we may experience a feeling of familiarity without conscious recall. Our amazing brains try to make sense of such an improbable situation, and we get an eerie feeling that we’re reliving some earlier part of our life. Our source amnesia forces us to do our best to make sense of an odd moment.

Discerning True and False Memories

To participate in a simulated experiment on false memory formation, and to review related research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Can You Trust Your Memory? For a 5-

To participate in a simulated experiment on false memory formation, and to review related research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Can You Trust Your Memory? For a 5-

Because memory is reconstruction as well as reproduction, we can’t be sure whether a memory is real by how real it feels. Much as perceptual illusions may seem like real perceptions, unreal memories feel like real memories.

False memories can be persistent. Imagine that we were to read aloud a list of words such as candy, sugar, honey, and taste. Later, we ask you to recognize the presented words from a larger list. If you are at all like the people tested by Henry Roediger and Kathleen McDermott (1995), you would err three out of four times—

Memory construction helps explain why about 75 percent of 301 convicts exonerated by later DNA testing had been misjudged based on faulty eyewitness identification (Lilienfeld & Byron, 2013). It explains why “hypnotically refreshed” memories of crimes so easily incorporate errors, some of which originate with the hypnotist’s leading questions (“Did you hear loud noises?”). It explains why dating partners who fell in love have overestimated their first impressions of one another (“It was love at first sight”), while those who broke up underestimated their earlier liking (“We never really clicked”) (McFarland & Ross, 1987). And it explains why people asked how they felt 10 years ago about marijuana or gender issues recalled attitudes closer to their current views than to the views they had actually reported a decade earlier (Markus, 1986). People tend to recall having always felt as they feel today (Mazzoni & Vannucci, 2007). As George Vaillant (1977, p. 197) noted after following adult lives through time, “It is all too common for caterpillars to become butterflies and then to maintain that in their youth they had been little butterflies. Maturation makes liars of us all.”

Children’s Eyewitness Recall

24-

If memories can be sincere, yet sincerely wrong, might children’s recollections of sexual abuse be prone to error? “It would be truly awful to ever lose sight of the enormity of child abuse,” observed Stephen Ceci (1993). Yet Ceci and Maggie Bruck’s (1993, 1995) studies of children’s memories have made them aware of how easily children’s memories can be molded. For example, they asked 3-

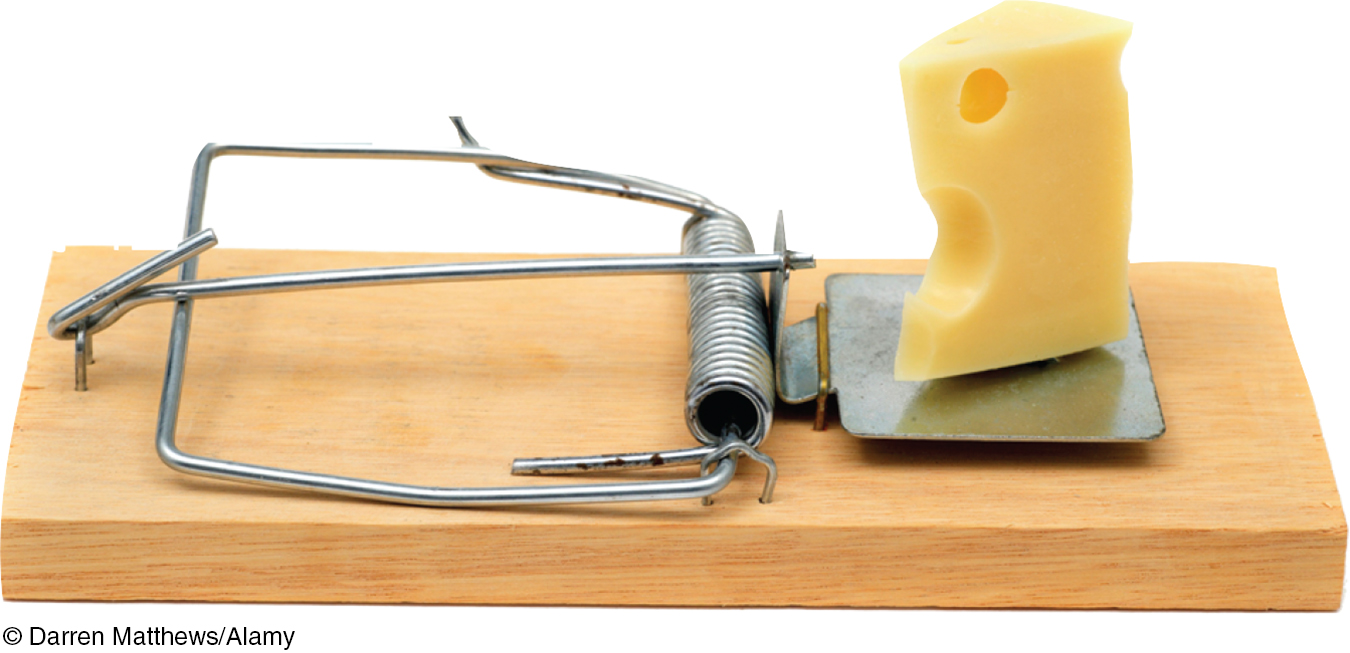

In other experiments, the researchers studied the effect of suggestive interviewing techniques (Bruck & Ceci, 1999, 2004). In one study, children chose a card from a deck of possible happenings, and an adult then read the card to them. For example, “Think real hard, and tell me if this ever happened to you. Can you remember going to the hospital with a mousetrap on your finger?” In interviews, the same adult repeatedly asked children to think about several real and fictitious events. After 10 weeks of this, a new adult asked the same question. The stunning result: 58 percent of preschoolers produced false (often vivid) stories regarding one or more events they had never experienced (Ceci et al., 1994). Here’s one:

My brother Colin was trying to get Blowtorch [an action figure] from me, and I wouldn’t let him take it from me, so he pushed me into the wood pile where the mousetrap was. And then my finger got caught in it. And then we went to the hospital, and my mommy, daddy, and Colin drove me there, to the hospital in our van, because it was far away. And the doctor put a bandage on this finger.

Given such detailed stories, professional psychologists who specialize in interviewing children could not reliably separate the real memories from the false ones. Nor could the children themselves. The above child, reminded that his parents had told him several times that the mousetrap incident never happened—

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If People’s Memories Are Accurate?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If People’s Memories Are Accurate?

Children can, however, be accurate eyewitnesses. When questioned about their experiences in neutral words they understood, children often accurately recalled what happened and who did it (Goodman, 2006; Howe, 1997; Pipe, 1996). And when interviewers used less suggestive, more effective techniques, even 4-

Like children (whose frontal lobes have not fully matured), older adults—