22.1 Studying Memory

22-

memory the persistence of learning over time through the encoding, storage, and retrieval of information.

Memory is learning that persists over time; it is information that has been acquired and stored and can be retrieved. Research on memory’s extremes has helped us understand how memory works. At age 92, my [DM’s] father suffered a small stroke that had but one peculiar effect. He was as mobile as before. His genial personality was intact. He knew us and enjoyed poring over family photo albums and reminiscing about his past. But he had lost most of his ability to lay down new memories of conversations and everyday episodes. He could not tell me what day of the week it was, or what he’d had for lunch. Told repeatedly of his brother-

At the other extreme are people who would be gold medal winners in a memory Olympics. Russian journalist Solomon Shereshevskii, or S, had merely to listen while other reporters scribbled notes (Luria, 1968). We could parrot back a string of about 7—

Amazing? Yes, but consider your own impressive memory. You remember countless faces, places, and happenings; tastes, smells, and textures; voices, sounds, and songs. In one study, students listened to snippets—

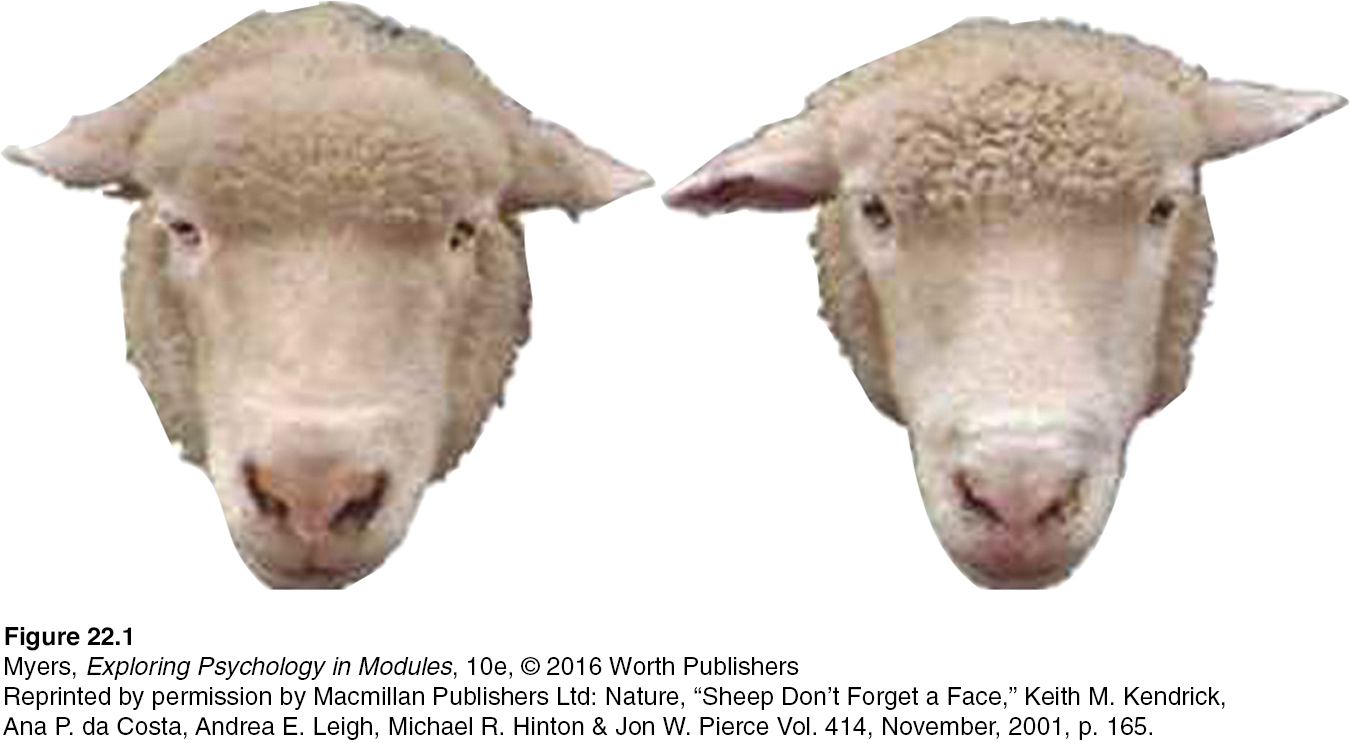

So, too, with faces and places. Imagine viewing more than 2500 slides of faces and places for 10 seconds each. Later, you see 280 of these slides, paired with others you’ve never seen. Actual participants in this experiment recognized 90 percent of the slides they had viewed in the first round (Haber, 1970). In a follow-

How do we accomplish such memory feats? How does our brain pluck information from the world around us and tuck that information away for later use? How can we remember things we have not thought about for years, yet forget the name of someone we met a minute ago? How are memories stored in our brain? Why will you be likely, later in this chapter, to misrecall this sentence: “The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”? In this chapter, we’ll consider these fascinating questions and more, including tips on how we can improve our own memories.

Measuring Retention

To a psychologist, evidence that learning persists includes these three measures of retention:

recall a measure of memory in which the person must retrieve information learned earlier, as on a fill-

recognition a measure of memory in which the person identifies items previously learned, as on a multiple-

relearning a measure of memory that assesses the amount of time saved when learning material again.

recall—retrieving information that is not currently in your conscious awareness but that was learned at an earlier time. A fill-

in- the- blank question tests your recall. recognition—identifying items previously learned. A multiple-

choice question tests your recognition. relearning—learning something more quickly when you learn it a second or later time. When you study for a final exam or engage a language used in early childhood, you will relearn the material more easily than you did initially.

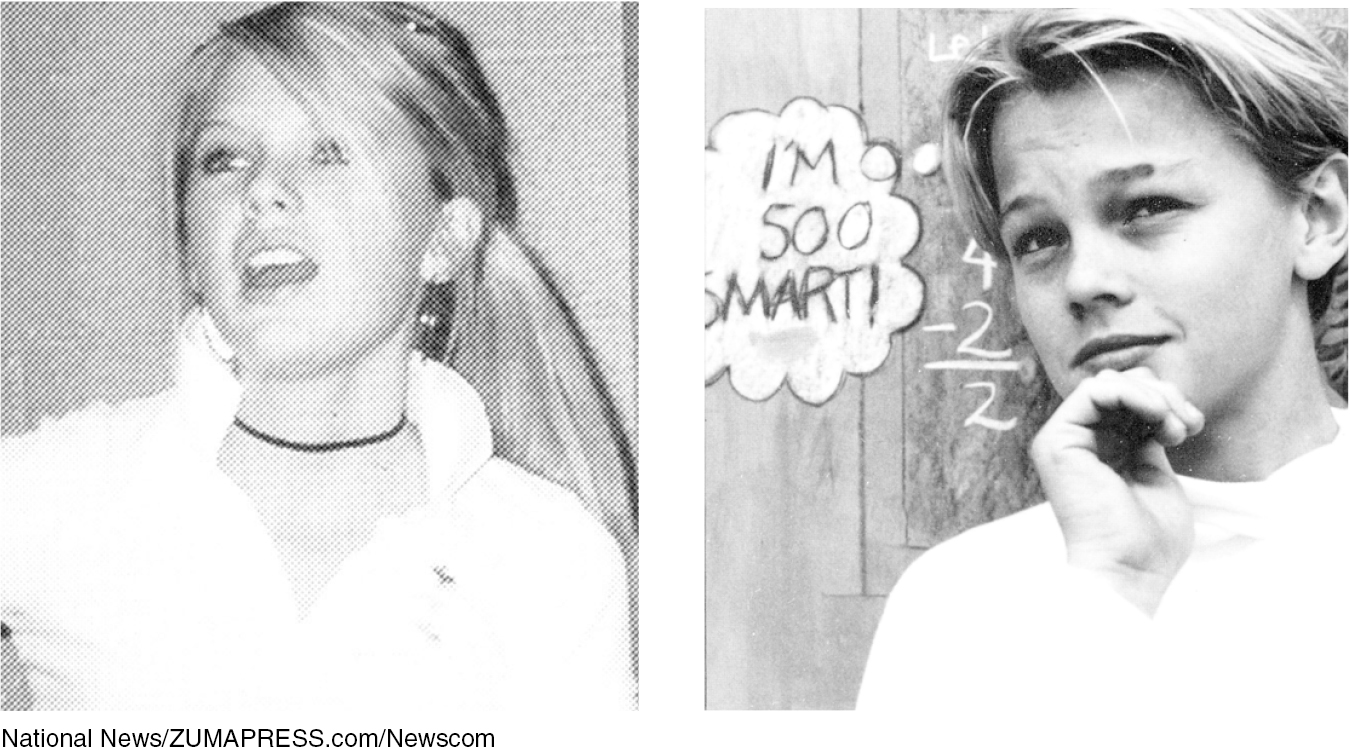

Long after you cannot recall most of the people in your high school graduating class, you may still be able to recognize their yearbook pictures from a photographic lineup and pick their names from a list. In one experiment, people who had graduated 25 years earlier could not recall many of their old classmates. But they could recognize 90 percent of their pictures and names (Bahrick et al., 1975). If you are like most students, you, too, could probably recognize more names of Snow White’s seven dwarfs than you could recall (Miserandino, 1991).

Our recognition memory is impressively quick and vast. “Is your friend wearing a new or old outfit?” “Old.” “Is this five-

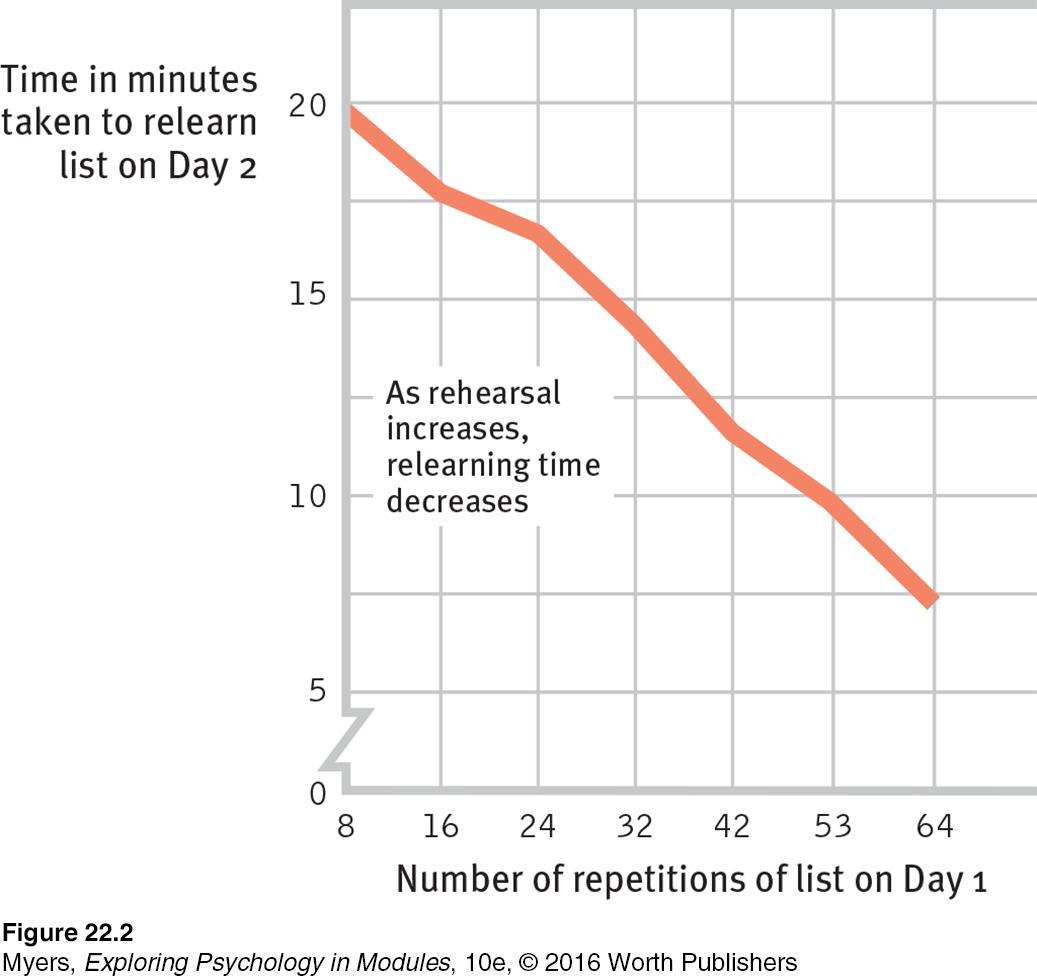

Our response speed when recalling or recognizing information indicates memory strength, as does our speed at relearning. Pioneering memory researcher Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–

JIH, BAZ, FUB, YOX, SUJ, XIR, DAX, LEQ, VUM, PID, KEL, WAV, TUV, ZOF, GEK, HIW.

The day after learning such a list, Ebbinghaus could recall few of the syllables. But they weren’t entirely forgotten. As FIGURE 22.2 portrays, the more frequently he repeated the list aloud on Day 1, the less time he required to relearn the list on Day 2. Additional rehearsal (overlearning) of verbal information increases retention, especially when practice is distributed over time. For students, this means that it helps to rehearse course material even after you know it.

The point to remember: Tests of recognition and of time spent relearning demonstrate that we remember more than we can recall.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Multiple-

Question

If you want to be sure to remember what you're learning for an upcoming test, would it be better to use recall or recognition to check your memory? Why?

Memory Models

22-

Architects make miniature house models to help clients imagine their future homes. Similarly, psychologists create memory models to help us think about how our brain forms and retrieves memories. An information-

encoding the processing of information into the memory system—

storage the process of retaining encoded information over time.

retrieval the process of getting information out of memory storage.

get information into our brain, a process called encoding.

retain that information, a process called storage.

later get the information back out, a process called retrieval.

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Like all analogies, computer models have their limits. Our memories are less literal and more fragile than a computer’s. Moreover, most computers process information sequentially, even while alternating between tasks. Our agile brain processes many things simultaneously (some of them unconsciously) by means of parallel processing.

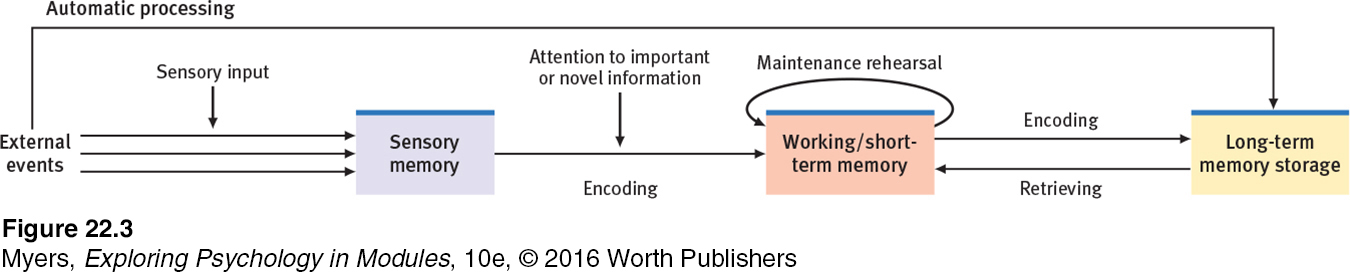

To focus on multitrack processing, one information-

To explain our memory-

sensory memory the immediate, very brief recording of sensory information in the memory system.

short-term memory activated memory that holds a few items briefly, such as the seven digits of a phone number while calling, before the information is stored or forgotten.

long-term memory the relatively permanent and limitless storehouse of the memory system. Includes knowledge, skills, and experiences.

We first record to-

be- remembered information as a fleeting sensory memory. From there, we process information into short-term memory, where we encode it through rehearsal.

Finally, information moves into long-term memory for later retrieval.

Other psychologists have updated this model (FIGURE 22.3) with important newer concepts, including working memory and automatic processing.

working memory a newer understanding of short-

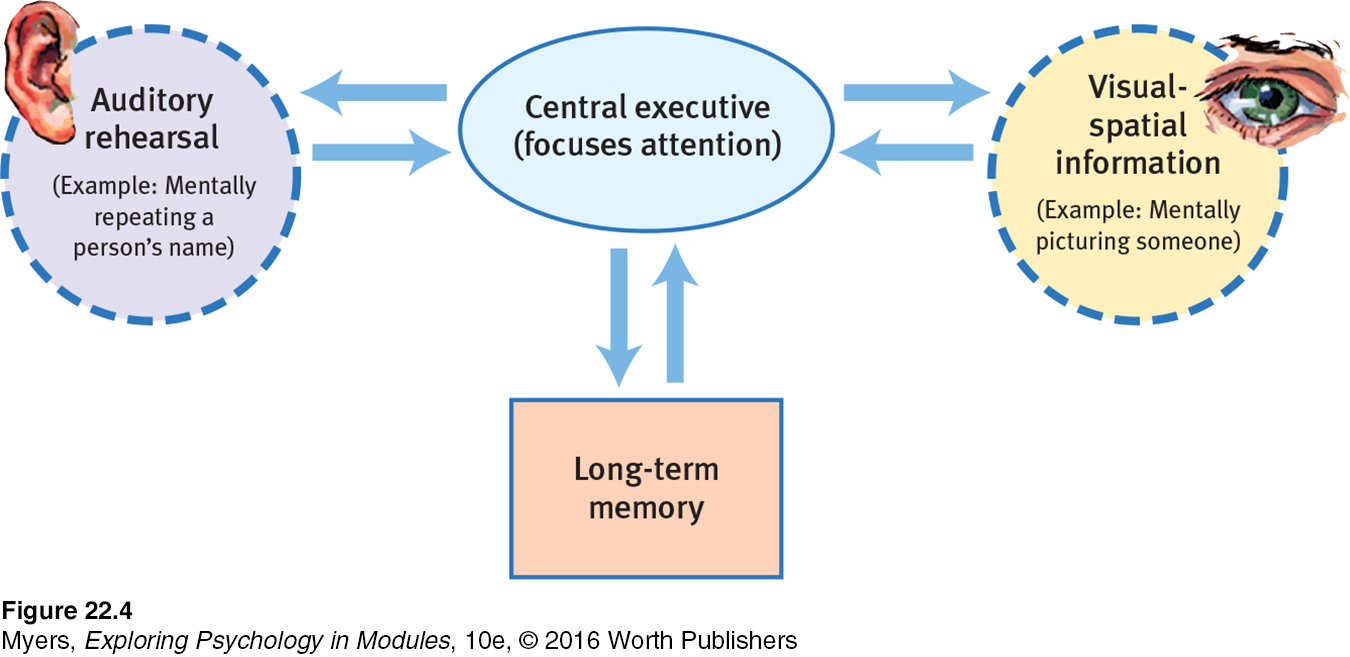

WORKING MEMORY Alan Baddeley and others (Baddeley, 2001, 2002; Barrouillet et al., 2011; Engle, 2002) extended Atkinson and Shiffrin’s view of short-

For most of you, what you are reading enters working memory through vision. You might also repeat the information using auditory rehearsal. As you integrate these memory inputs with your existing long-

For a 14-

For a 14-

Without focused attention, information often fades. If you think you can look something up later, you attend to it less and forget it more quickly. In one experiment, people read and typed new bits of trivia they would later need, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” If they knew the information would be available online, they invested less energy and remembered it less well (Sparrow et al., 2011; Wegner & Ward, 2013). Sometimes Google replaces rehearsal.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How does the working memory concept update the classic Atkinson-

Question

What are two basic functions of working memory?