22.2 Encoding Memories

Dual-

22-

explicit memory memory of facts and experiences that one can consciously know and “declare.” (Also called declarative memory.)

effortful processing encoding that requires attention and conscious effort.

automatic processing unconscious encoding of incidental information, such as space, time, and frequency, and of well-

implicit memory retention of learned skills or classically conditioned associations independent of conscious recollection. (Also called nondeclarative memory.)

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s model focused on how we process our explicit memories—

Automatic Processing and Implicit Memories

22-

Our implicit memories include procedural memory for automatic skills (such as how to ride a bike) and classically conditioned associations among stimuli. If attacked by a dog in childhood, years later you may, without recalling the conditioned association, automatically tense up as a dog approaches.

Without conscious effort you also automatically process information about

space. While studying, you often encode the place on a page where certain material appears; later, when you want to retrieve the information, you may visualize its location on the page.

time. While going about your day, you unintentionally note the sequence of its events. Later, realizing you’ve left your coat somewhere, the event sequence your brain automatically encoded will enable you to retrace your steps.

frequency. You effortlessly keep track of how many times things happen, as when you realize, This is the third time I’ve run into her today.

Our two-

Effortful Processing and Explicit Memories

Automatic processing happens effortlessly. When you see words in your native language, perhaps on the side of a delivery truck, you can’t help but read them and register their meaning. Learning to read wasn’t automatic. You may recall working hard to pick out letters and connect them to certain sounds. But with experience and practice, your reading became automatic. Imagine now learning to read sentences in reverse:

.citamotua emoceb nac gnissecorp luftroffE

At first, this requires effort, but after enough practice, you would also perform this task much more automatically. We develop many skills in this way: driving, texting, and speaking a new language.

SENSORY MEMORY

22-

Sensory memory (recall FIGURE 22.3) feeds our active working memory, recording momentary images of scenes or echoes of sounds. How much of this page could you sense and recall with less exposure than a lightning flash? In one experiment, people viewed three rows of three letters each, for only one-

Was it because they had insufficient time to glimpse them? No. The researcher, George Sperling, cleverly demonstrated that people actually could see and recall all the letters, but only momentarily. Rather than ask them to recall all nine letters at once, he sounded a high, medium, or low tone immediately after flashing the nine letters. This tone directed participants to report only the letters of the top, middle, or bottom row, respectively. Now they rarely missed a letter, showing that all nine letters were momentarily available for recall.

iconic memory a momentary sensory memory of visual stimuli; a photographic or picture-

Sperling’s experiment demonstrated iconic memory, a fleeting sensory memory of visual stimuli. For a few tenths of a second, our eyes register a photographic (picture-

echoic memory a momentary sensory memory of auditory stimuli; if attention is elsewhere, sounds and words can still be recalled within 3 or 4 seconds.

We also have an impeccable, though fleeting, memory for auditory stimuli, called echoic memory (Cowan, 1988; Lu et al., 1992). Picture yourself becoming distracted by a text message while in conversation with a friend. If your mildly irked companion tests you by asking, “What did I just say?” you can recover the last few words from your mind’s echo chamber. Auditory echoes tend to linger for 3 or 4 seconds.

SHORT-

22-

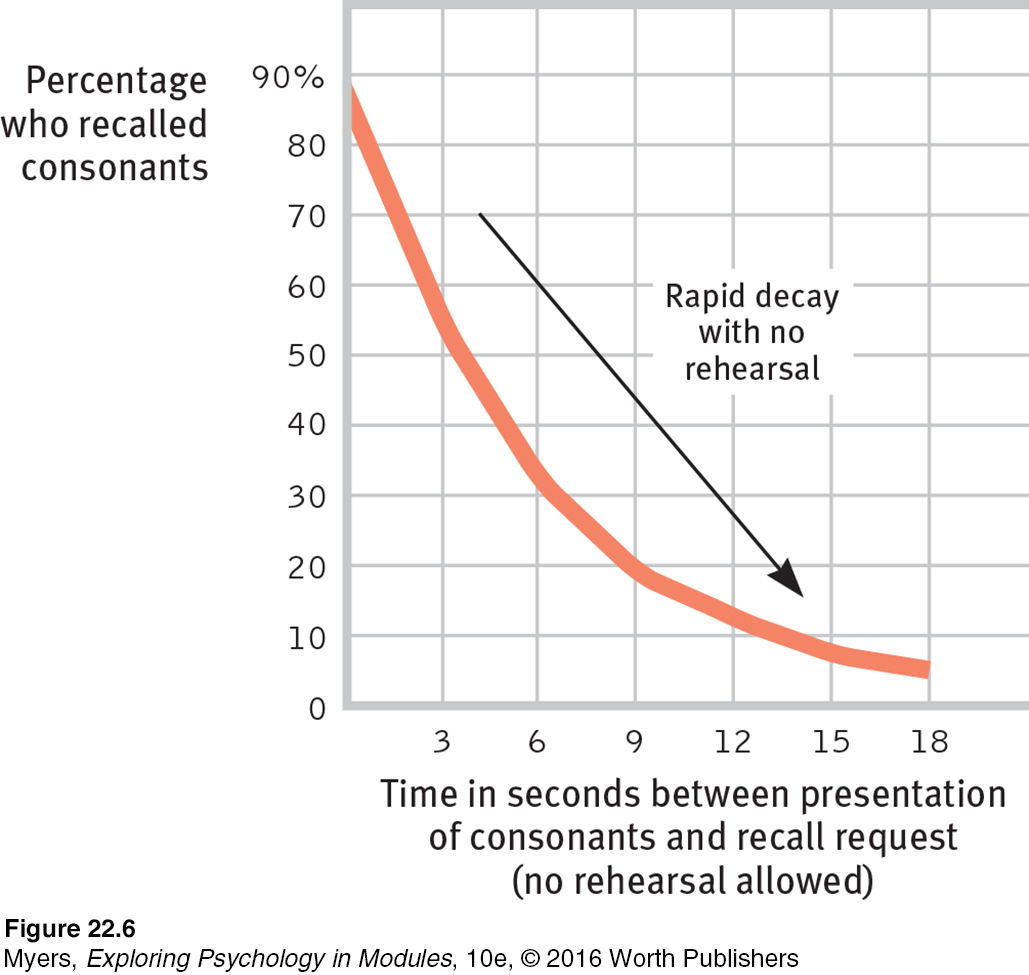

Recall that short-

George Miller (1956) proposed that we can store about seven pieces of information (give or take two) in short-

After Miller’s 2012 death, his daughter recalled his best moment of golf: “He made the one and only hole-

Working-

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the difference between automatic and effortful processing, and what are some examples of each?

Question

At which of Atkinson-

EFFORTFUL PROCESING STRATEGIES

22-

Several effortful processing strategies can boost our ability to form new memories. Later, when we try to retrieve a memory, these strategies can make the difference between success and failure.

chunking organizing items into familiar, manageable units; often occurs automatically.

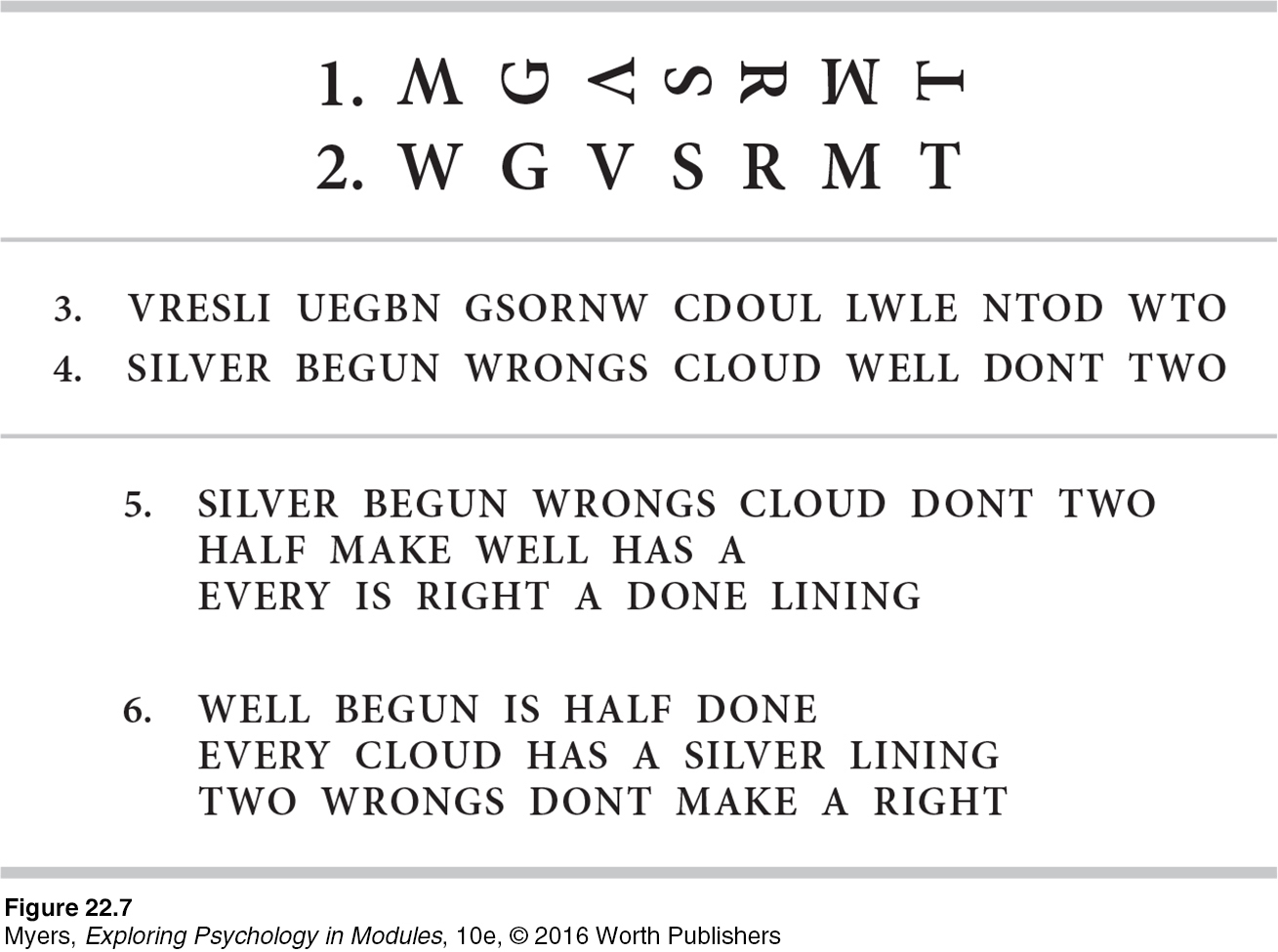

CHUNKING Glance for a few seconds at the first set of letters in FIGURE 22.7 below, then look away and try to reproduce what you saw. Impossible, yes? But you can easily reproduce set 2, which is no less complex. Similarly, you will probably remember sets 4 and 6 more easily than the same elements in sets 3 and 5. As this demonstrates, chunking information—

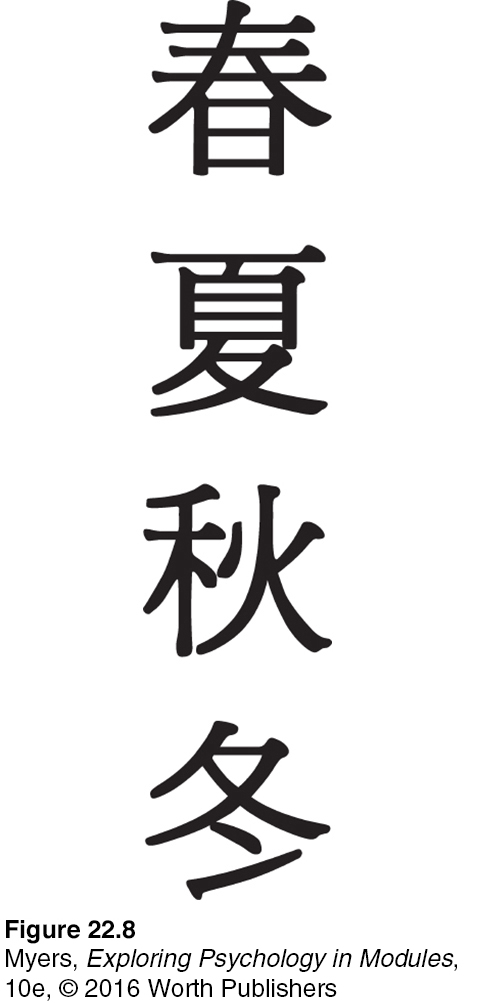

Chunking usually occurs so naturally that we take it for granted. If you are a native English speaker, you can reproduce perfectly the 150 or so line segments that make up the words in the three phrases of set 6 in FIGURE 22.7. It would astonish someone unfamiliar with the language. I am similarly awed by a Chinese reader’s ability to glance at FIGURE 22.8 and reproduce all the strokes, or a varsity basketball player’s recall of players’ positions after a 4-

mnemonics [nih-

MNEMONICS To help them encode lengthy passages and speeches, ancient Greek scholars and orators developed mnemonics. Many of these memory aids use vivid imagery, because we are particularly good at remembering mental pictures. We more easily remember concrete, visualizable words than we do abstract words. (When we quiz you later, which three of these words—

The peg-

When combined, chunking and mnemonic techniques can be great memory aids for unfamiliar material. Want to remember the colors of the rainbow in order of wavelength? Think of the mnemonic ROY G. BIV (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). Need to recall the names of North America’s five Great Lakes? Just remember HOMES (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior). In each case, we chunk information into a more familiar form by creating a word (called an acronym) from the first letters of the to-

HIERARCHIES When people develop expertise in an area, they process information not only in chunks but also in hierarchies composed of a few broad concepts divided and subdivided into narrower concepts and facts. (FIGURE 23.4 ahead provides a hierarchy of our automatic and effortful memory processing systems.)

Organizing knowledge in hierarchies helps us retrieve information efficiently, as Gordon Bower and his colleagues (1969) demonstrated by presenting words either randomly or grouped into categories. When the words were organized into categories, recall was two to three times better. Such results show the benefits of organizing what you study—

spacing effect the tendency for distributed study or practice to yield better long-

DISTRIBUTED PRACTICE We retain information better when our encoding is distributed over time. More than 300 experiments over the past century have consistently revealed the benefits of this spacing effect (Cepeda et al., 2006). Massed practice (cramming) can produce speedy short-

“The mind is slow in unlearning what it has been long in learning.”

Roman philosopher Seneca (4 B.C.E.-65 C.E.)

testing effect enhanced memory after retrieving, rather than simply rereading, information. Also sometimes referred to as a retrieval practice effect or test-

One effective way to distribute practice is repeated self-

The point to remember: Spaced study and self-

LEVELS OF PROCESSING

22-

shallow processing encoding on a basic level based on the structure or appearance of words.

deep processing encoding semantically, based on the meaning of the words; tends to yield the best retention.

Memory researchers have discovered that we process verbal information at different levels, and that depth of processing affects our long-

In one classic experiment, researchers Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving (1975) flashed words at viewers. Then they asked questions that would elicit different levels of processing. To experience the task yourself, rapidly answer the following sample questions:

| Sample Questions to Elicit Different Levels of Processing | Word Flashed | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most shallow: Is the word in capital letters? | CHAIR | _____ | _____ |

| Shallow: Does the word rhyme with train? | brain | _____ | _____ |

| Deep: Would the word fit in this sentence? The girl put the _____ on the table. | doll | _____ | _____ |

Which type of processing would best prepare you to recognize the words at a later time? In Craik and Tulving’s experiment, the deeper, semantic processing triggered by the third question yielded a much better memory than did the shallower processing elicited by the second question or the very shallow processing elicited by the first question (which was especially ineffective).

MAKING MATERIAL PERSONALLY MEANINGFUL If new information is not meaningful or related to our experience, we have trouble processing it. Put yourself in the place of the students who were asked to remember the following recorded passage:

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. . . . After the procedure is completed, one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.

When the students heard the paragraph you have just read, without a meaningful context, they remembered little of it (Bransford & Johnson, 1972). When told the paragraph described washing clothes (something meaningful), they remembered much more of it—

Can you repeat the sentence about the rioter that we gave you at this chapter’s beginning (“The angry rioter threw . . .”)?

Perhaps, like those in an experiment by William Brewer (1977), you recalled the sentence by the meaning you encoded when you read it (for example, “The angry rioter threw the rock through the window”) and not as it was written (“The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”). Referring to such mental mismatches, some researchers have likened our minds to theater directors who, given a raw script, imagine the finished stage production (Bower & Morrow, 1990). Asked later what we heard or read, we recall not the literal text but what we encoded. Thus, studying for an exam, you may remember your lecture notes rather than the lecture itself.

We can avoid some of these mismatches by rephrasing information into meaningful terms. From his experiments on himself, Ebbinghaus estimated that, compared with learning nonsense material, learning meaningful material required one-

Psychologist-

We have especially good recall for information we can meaningfully relate to ourselves. Asked how well certain adjectives describe someone else, we often forget them; asked how well the adjectives describe us, we remember the words well. This tendency, called the self-

The point to remember: The amount remembered depends both on the time spent learning and on your making it meaningful for deep processing.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which strategies are better for long-

Question

If you try to make the material you are learning personally meaningful, are you processing at a shallow or a deep level? Which level leads to greater retention?