Chapter 9 Introduction

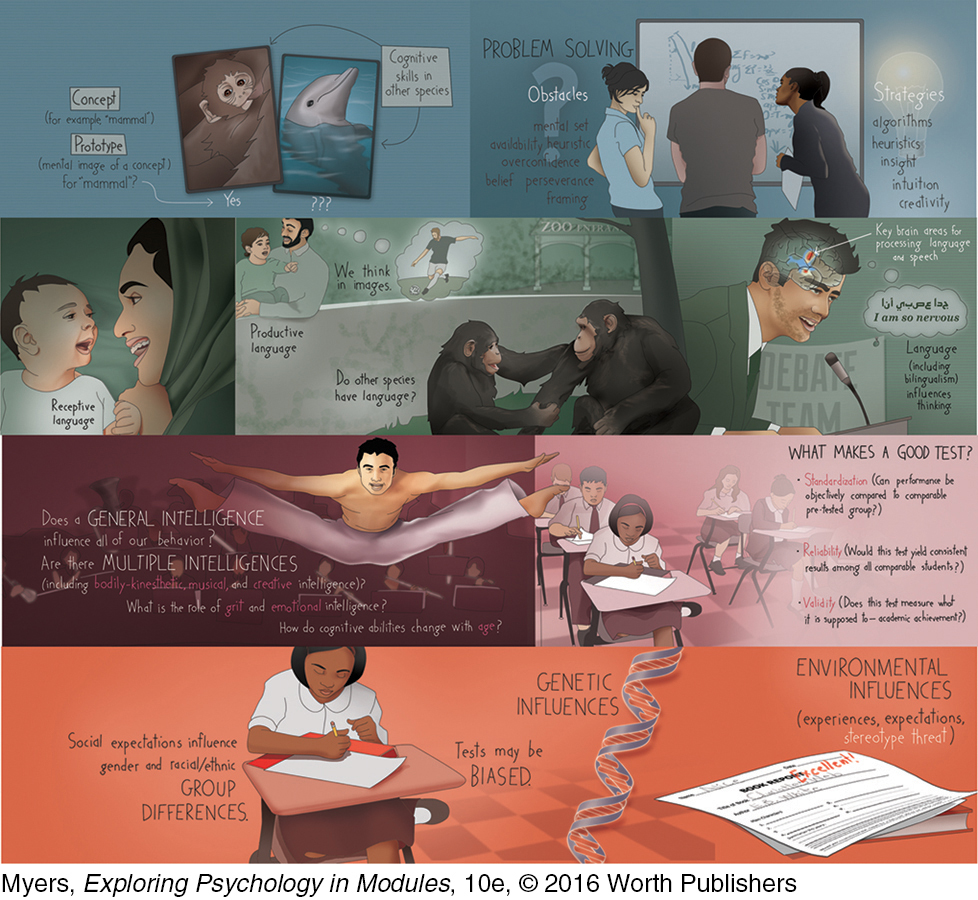

Thinking, Language, and Intelligence

Page 315

THROUGHOUT history, we humans have both celebrated our wisdom and bemoaned our foolishness. The poet T. S. Eliot was struck by “the hollow men . . . Headpiece filled with straw.” But Shakespeare’s Hamlet extolled the human species as “noble in reason! . . . infinite in faculties! . . . in apprehension how like a god!” Throughout this text, we likewise marvel at both our abilities and our errors.

We have studied the human brain—three pounds of wet tissue the size of a small cabbage, yet containing staggeringly complex circuitry. We have appreciated the amazing abilities of newborns. We have marveled at our visual system, which converts light waves into nerve impulses, distributes them for parallel processing, and reassembles them into colorful perceptions. We have pondered our memory’s enormous capacity, and the ease with which our two-track mind processes information, with and without our awareness. Little wonder that our species has had the collective genius to invent the camera, the car, and the computer; to unlock the atom and crack the genetic code; to travel out to space and into our brain’s depths.

Yet we have also seen that in other ways, we are less than noble in reason. Our species is kin to the other animals, influenced by the same principles that produce learning in rats and pigeons. We note that we not-so-wise humans are easily deceived by perceptual illusions, pseudopsychic claims, and false memories.

In Modules 25 through 28, we encounter further instances of these two aspects of the human condition—the rational and the irrational. We will consider how we use and misuse the information we receive, perceive, store, and retrieve. We will look at our gift for language and intelligence. And we will reflect on how deserving we are of our species name, Homo sapiens—wise human.