27.1 What Is Intelligence?

intelligence the mental potential to learn from experience, solve problems, and use knowledge to adapt to new situations.

27-

In many studies, intelligence has been defined as whatever intelligence tests measure, which has tended to be school smarts. But intelligence is not a quality like height or weight, which has the same meaning to everyone worldwide. People assign the term intelligence to the qualities that enable success in their own time and culture (Sternberg & Kaufman, 1998). In Cameroon’s equatorial forest, intelligence may reflect understanding the medicinal qualities of local plants. In a North American high school, it may reflect mastering difficult concepts in tough courses. In both places, intelligence is the mental potential to learn from experience, solve problems, and use knowledge to adapt to new situations.

You probably know some people with talents in science, others who excel in the humanities, and still others gifted in athletics, art, music, or dance. You may also know a talented artist who is stumped by the simplest math problem, or a brilliant math student who struggles when discussing literature. Are all these people intelligent? Could you rate their intelligence on a single scale? Or would you need several different scales? Simply put, is intelligence a single overall ability or several specific abilities?

Spearman’s General Intelligence Factor

general intelligence (g) a general intelligence factor that, according to Spearman and others, underlies specific mental abilities and is therefore measured by every task on an intelligence test.

Charles Spearman (1863–

“g is one of the most reliable and valid measures in the behavioral domain . . . and it predicts important social outcomes such as educational and occupational levels far better than any other trait.”

Behavior geneticist Robert Plomin (1999)

Spearman’s belief stemmed in part from his work with factor analysis, a statistical procedure that identifies clusters of related items. In this view, mental abilities are much like physical abilities: The ability to run fast is distinct from the eye-

Theories of Multiple Intelligences

27-

Other psychologists, particularly since the mid-

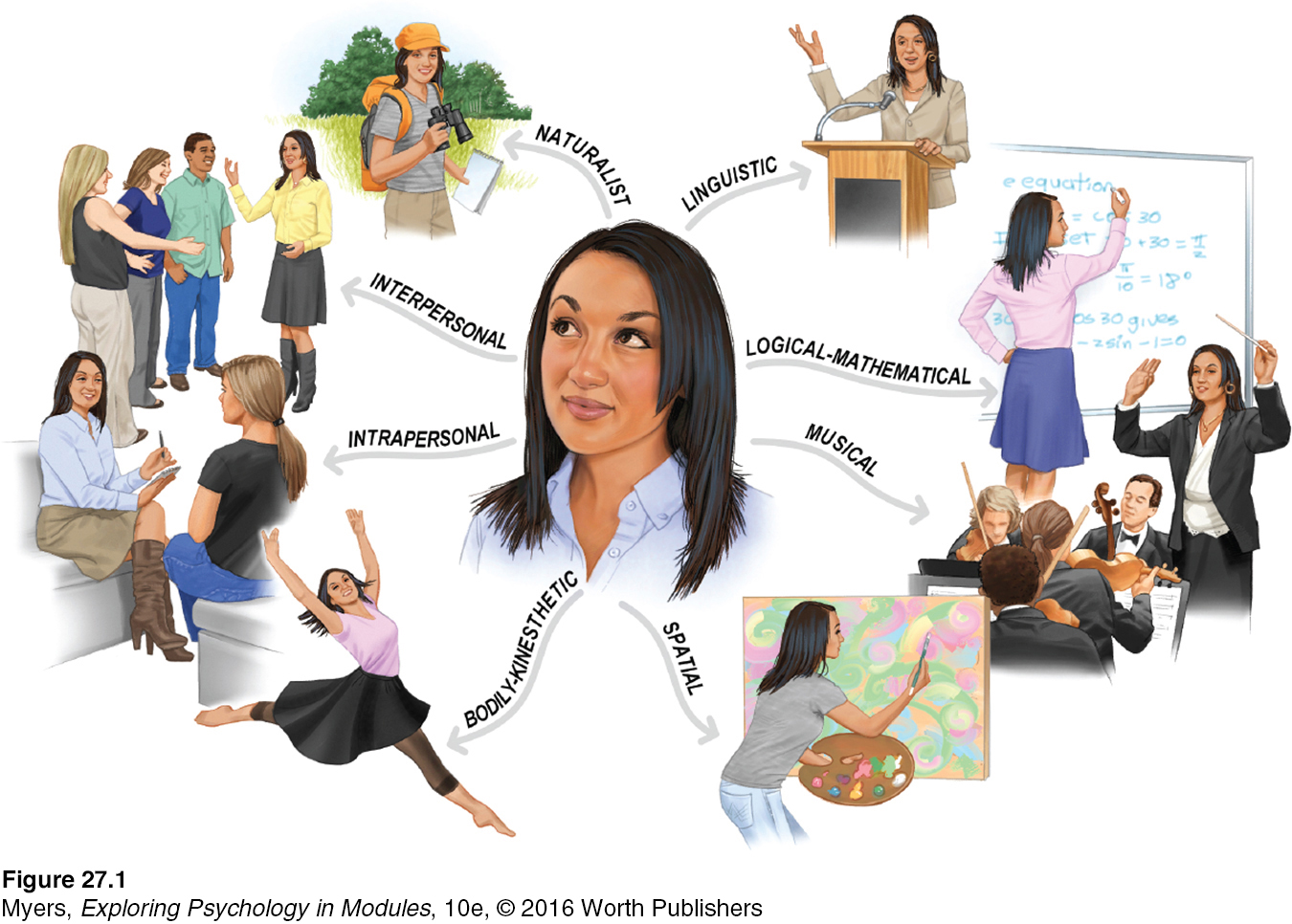

GARDNER’S MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES Howard Gardner has identified eight relatively independent intelligences, including the verbal and mathematical aptitudes assessed by standardized tests (FIGURE 27.1 below). Thus, the computer programmer, the poet, the street-

savant syndrome a condition in which a person otherwise limited in mental ability has an exceptional specific skill, such as in computation or drawing.

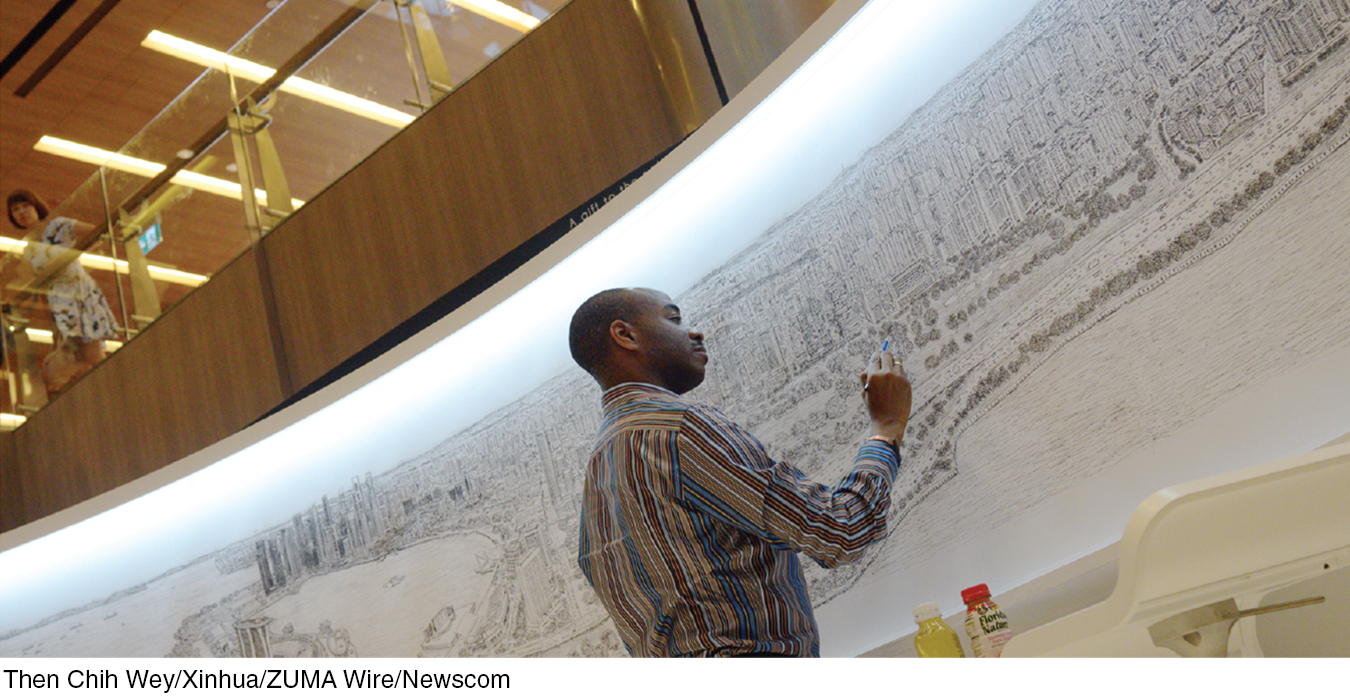

Gardner (1983, 2006, 2011; Davis et al., 2011) views these intelligence domains as multiple abilities that come in different packages. Brain damage, for example, may destroy one ability but leave others intact. And consider people with savant syndrome. Despite their island of brilliance, these people often score low on intelligence tests and may have limited or no language ability (Treffert & Wallace, 2002). Some can compute complicated calculations quickly and accurately, or identify almost instantly the day of the week corresponding to any historical date, or render incredible works of art or musical performance (Miller, 1999).

About four in five people with savant syndrome are males. Many also have autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental disorder. The late memory whiz Kim Peek (who did not have ASD) inspired the movie Rain Man. In 8 to 10 seconds, he could read and remember a page. During his lifetime, he memorized 9000 books, including Shakespeare’s works and the Bible. He could provide GPS-

“You have to be careful, if you’re good at something, to make sure you don’t think you’re good at other things that you aren’t necessarily so good at. . . . Because I’ve been very successful at [software development] people come in and expect that I have wisdom about topics that I don’t.”

Philanthropist Bill Gates (1998)

STERNBERG’S THREE INTELLIGENCES Robert Sternberg (1985, 2011) agrees with Gardner that there is more to success than traditional intelligence and that we have multiple intelligences. But his triarchic theory proposes three, not eight or nine, intelligences:

Analytical intelligence (school smarts; traditional academic problem solving)

Creative intelligence (the ability to react adaptively to new situations and generate novel ideas)

Practical intelligence (street smarts; skill at handling everyday tasks, which may be ill defined, with multiple solutions)

Gardner and Sternberg differ in some areas, but they agree on two important points: Multiple abilities can contribute to life success, and varieties of giftedness bring spice to life and challenges for education. As a result of this research, many teachers have been trained to appreciate such variety and to apply multiple intelligence theories in their classrooms.

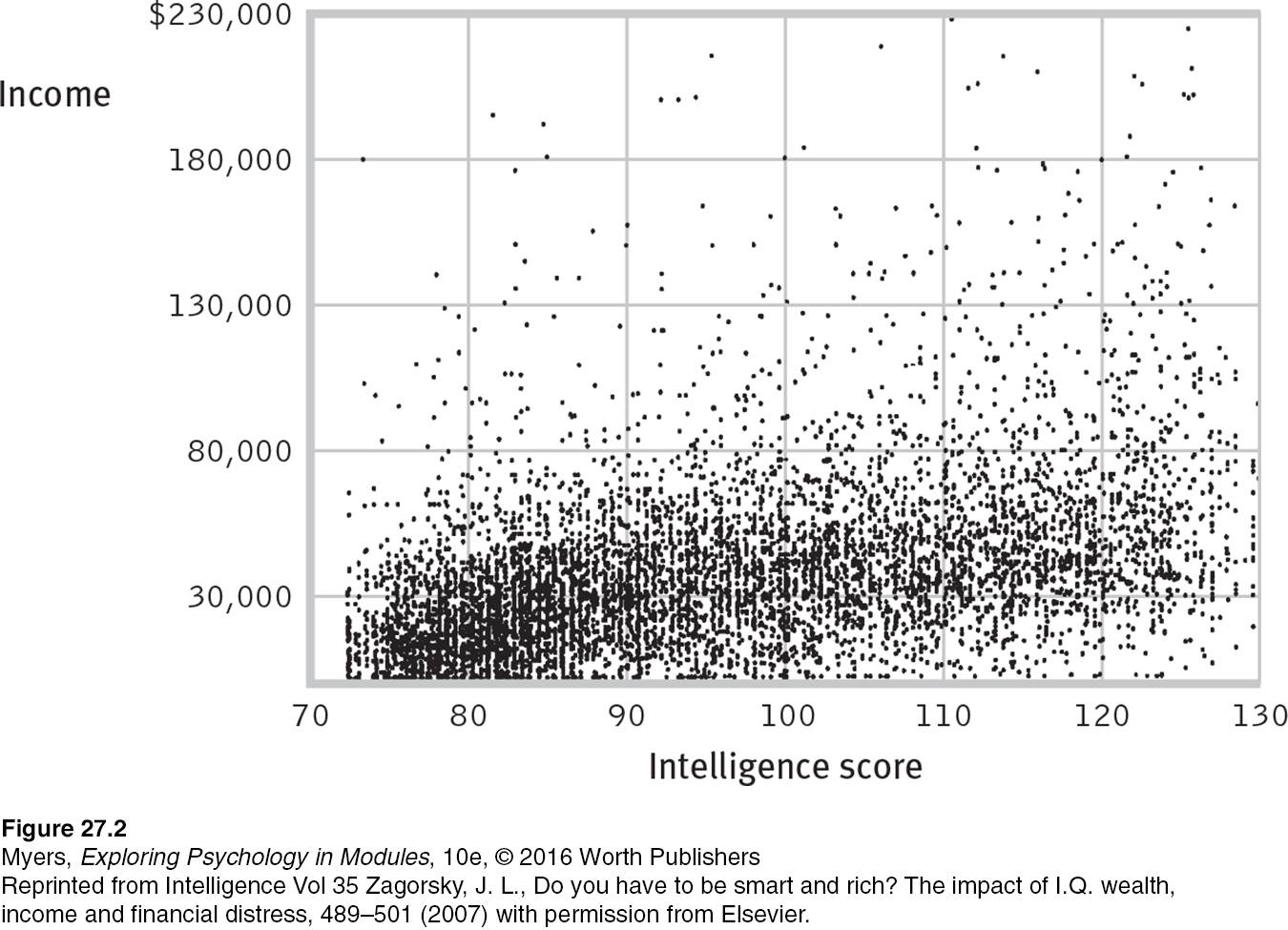

CRITICISMS OF MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCE THEORIES Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the world were so just that a weakness in one area would be compensated by genius in another? Alas, say critics, the world is not just (Ferguson, 2009; Scarr, 1989). Research using factor analysis has confirmed that there is a general intelligence factor (Johnson et al., 2008): g matters. It predicts performance on various complex tasks and in various jobs (Gottfredson, 2002a,b, 2003a,b; see also FIGURE 27.2). Much as jumping ability is not a predictor of jumping performance when the bar is set a foot off the ground—

Even so, “success” is not a one-

Bees, birds, chimpanzees, and other species also require time and experience to acquire peak expertise in skills such as foraging (Helton, 2008). As with humans, performance tends to peak near midlife.

See the Motivation and Emotion modules for more on how self-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How does the existence of savant syndrome support Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences?

Emotional Intelligence

27-

Is being in tune with yourself and others also a sign of intelligence, distinct from academic intelligence? Some researchers say Yes. They define social intelligence as the know-

emotional intelligence the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and use emotions.

One line of research has explored a specific aspect of social intelligence called emotional intelligence, consisting of four abilities (Mayer et al., 2002, 2011, 2012):

Perceiving emotions (recognizing them in faces, music, and stories)

Understanding emotions (predicting them and how they may change and blend)

Page 345Managing emotions (knowing how to express them in varied situations)

Using emotions to enable adaptive or creative thinking

Emotionally intelligent people are both socially aware and self-

Some scholars, however, are concerned that emotional intelligence stretches the intelligence concept too far (Visser et al., 2006). Howard Gardner (1999) includes interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences as two of his multiple intelligences. But let us instead, he offers, respect emotional sensitivity, creativity, and motivation as important but different. Stretch intelligence to include everything we prize and the word will lose its meaning.

The procrastinator’s motto: “Hard work pays off later; laziness pays off now.”

* * *

For a summary of these theories of intelligence, see TABLE 27.1.

Comparing Theories of Intelligence

| Theory | Summary | Strengths | Other Considerations |

| Spearman’s general intelligence (g) | A basic intelligence predicts our abilities in varied academic areas. | Different abilities, such as verbal and spatial, do have some tendency to correlate. | Human abilities are too diverse to be encapsulated by a single general intelligence factor. |

| Gardner’s multiple intelligences | Our abilities are best classified into eight or nine independent intelligences, which include a broad range of skills beyond traditional school smarts. | Intelligence is more than just verbal and mathematical skills. Other abilities are equally important to our human adaptability. | Should all of our abilities be considered intelligences? Shouldn’t some be called less vital talents? |

| Sternberg’s triarchic theory | Our intelligence is best classified into three areas that predict real- |

These three domains can be reliably measured. |

1. These three domains may be less independent than Sternberg thought and may actually share an underlying g factor. 2. Additional testing is needed to determine whether these domains can reliably predict success. |

| Emotional intelligence | Social intelligence is an important indicator of life success. Emotional intelligence is a key aspect, consisting of perceiving, understanding, managing, and using emotions. | The four components that predict social success. | Does this stretch the concept of intelligence too far? |