27.3 The Dynamics of Intelligence

Aging and Intelligence

27-

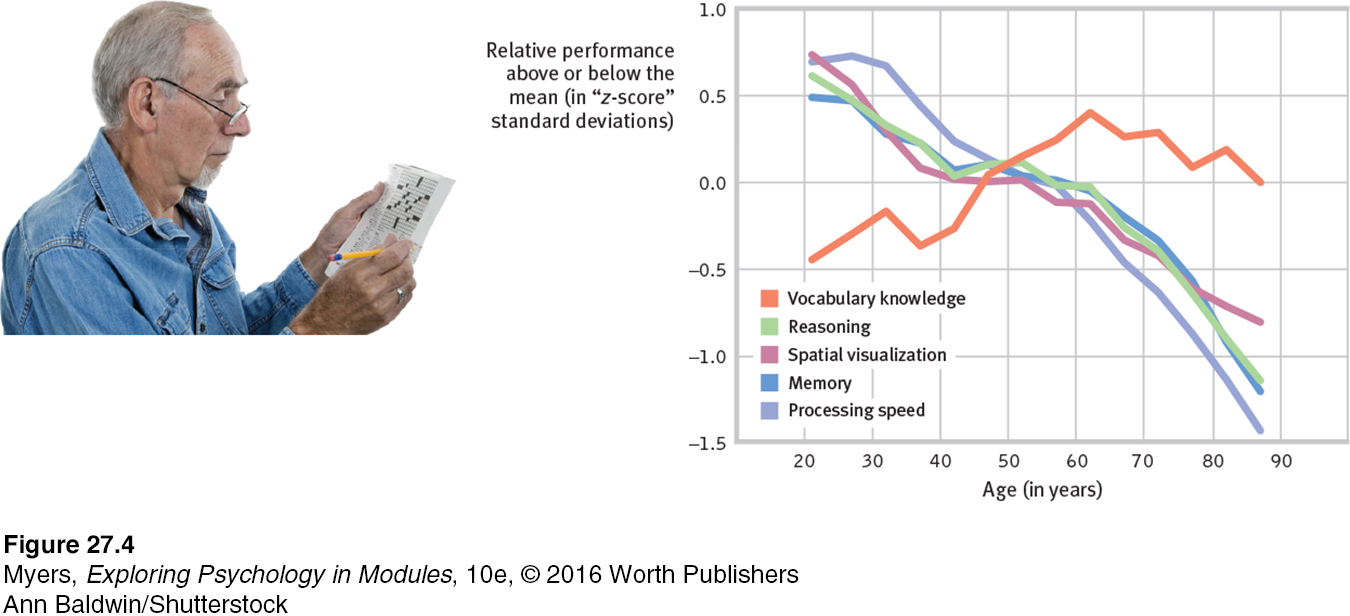

Does intelligence increase, decrease, or remain constant as we age? The answer depends on the type of intellectual performance we measure:

crystallized intelligence our accumulated knowledge and verbal skills; tends to increase with age.

fluid intelligence our ability to reason speedily and abstractly; tends to decrease with age, especially during late adulthood.

Crystallized intelligence—our accumulated knowledge as reflected in vocabulary and analogies tests—

increases up to old age. Fluid intelligence—our ability to reason speedily and abstractly, as when solving novel logic problems—

decreases beginning in the twenties and thirties, slowly up to age 75 or so, then more rapidly, especially after age 85 (Cattell, 1963; Horn, 1982; Salthouse, 2009; 2013).

How do we know? Developmental psychologists use longitudinal studies (restudying the same group at different times across their life span) and cross-sectional studies (comparing members of different age groups at the same time) to study the way intelligence and other traits change with age. (See Appendix A for more information.) With age we lose and we win. We lose recall memory and processing speed, but we gain vocabulary and knowledge (FIGURE 27.4 below). Fluid intelligence may decline, but older adults’ social reasoning skills increase, as shown by an ability to take multiple perspectives, to appreciate knowledge limits, and to offer helpful wisdom in times of social conflict (Grossman et al., 2010). Decisions also become less distorted by negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and anger (Blanchard-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

“Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit; wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.”

Anonymous

Age-

“In youth we learn, in age we understand.”

Marie Von Ebner-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Researcher A is well funded to learn about how intelligence changes over the life span. Researcher B wants to study the intelligence of people who are now at various life stages. Which researcher should use the cross-

Stability Over the Life Span

27-

What about the stability of early-

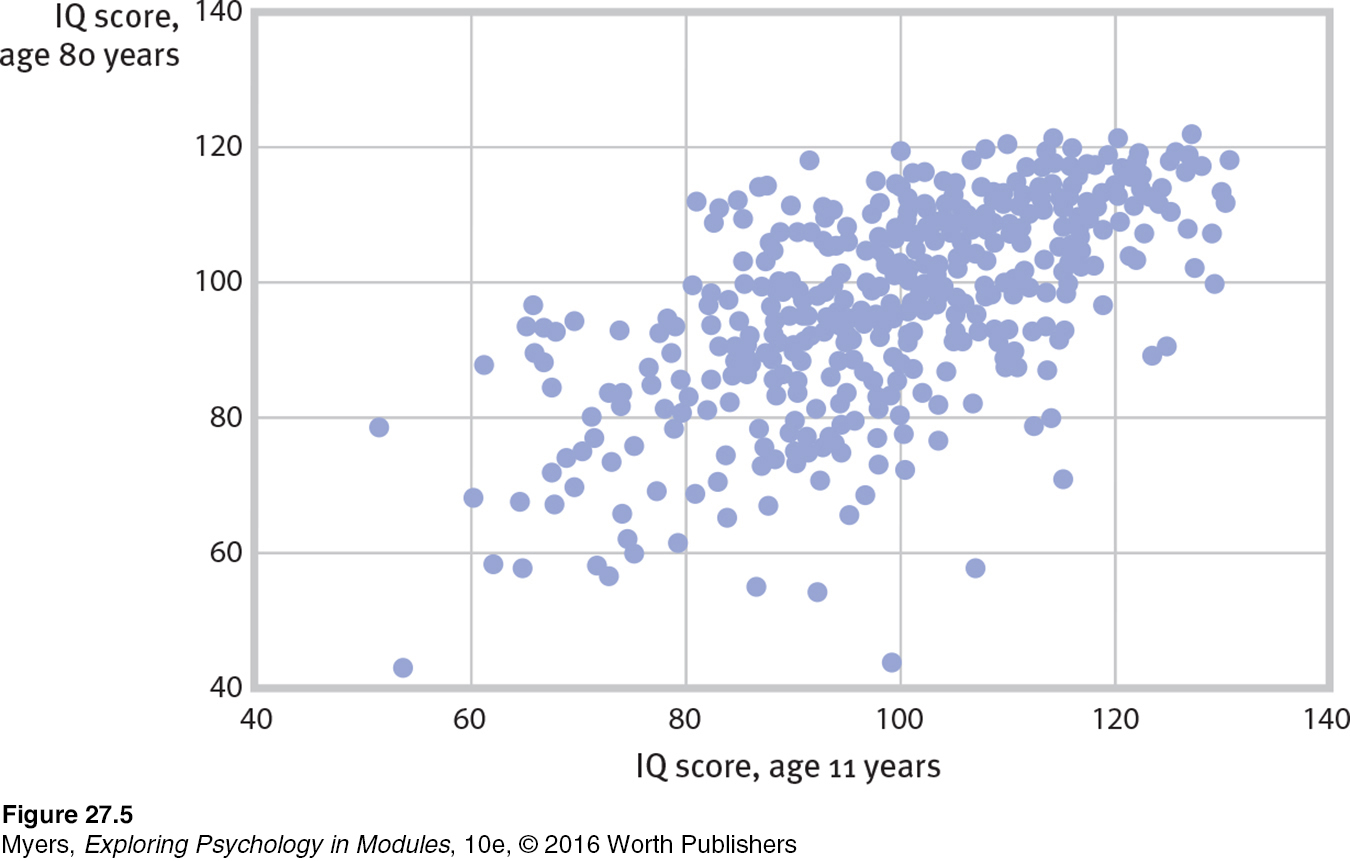

By age 4, however, children’s performance on intelligence tests begins to predict their adolescent and adult scores. The consistency of scores over time increases with the age of the child. By age 11, the stability becomes impressive, as Ian Deary and his colleagues (2004, 2009, 2013) discovered. Their amazing longitudinal studies have been enabled by their country, Scotland, which did something that no nation has done before or since. On June 1, 1932, essentially every child in the country born in 1921—

And so it has, with dozens of studies of the stability and the predictive capacity of these early test results. For example, when the intelligence test administered to 11-

“Whether you live to collect your old-

Ian Deary, “Intelligence, Health, and Death,” 2005

Children and adults who are more intelligent also tend to live healthier and longer lives. Why might this be the case? Deary (2008) proposes four possible explanations:

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Explore how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Intelligence Changes With Age?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Explore how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Intelligence Changes With Age?

Intelligence facilitates more education, better jobs, and a healthier environment.

Intelligence encourages healthy living: less smoking, better diet, more exercise.

Prenatal events or early childhood illnesses might have influenced both intelligence and health.

A “well-

wired body,” as evidenced by fast reaction speeds, perhaps fosters both intelligence and longevity.

Extremes of Intelligence

27-

One way to glimpse the validity and significance of any test is to compare people who score at the two extremes of the normal curve. The two groups should differ noticeably, and with intelligence testing, they do.

intellectual disability a condition of limited mental ability, indicated by an intelligence test score of 70 or below and difficulty adapting to the demands of life. (Formerly referred to as mental retardation.)

THE LOW EXTREME At one extreme of the intelligence test normal curve are those with unusually low scores. The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities guidelines list two criteria for a diagnosis of intellectual disability (formerly referred to as mental retardation):

A test score indicating performance below 98 percent of test-

takers (Schalock et al., 2010). For an intelligence test with a midpoint of 100, that is a score of approximately 70 or below. Difficulty adapting to the normal demands of independent living, as expressed in three areas:

conceptual skills (such as language, literacy, and concepts of money, time, and number).

social skills (such as interpersonal skills, social responsibility, following basic rules and laws, and avoiding being victimized).

practical skills (such as daily personal care, occupational skill, travel, and health care).

Down syndrome a condition of mild to severe intellectual disability and associated physical disorders caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21.

Intellectual disability is a developmental condition that is apparent before age 18, sometimes with a known physical cause. Down syndrome, for example, is a disorder of varying intellectual and physical severity caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21.

People diagnosed with a mild intellectual disability—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why do psychologists NOT diagnose an intellectual disability based solely on a person's intelligence test score?

THE HIGH EXTREME In one famous project begun in 1921, Lewis Terman studied more than 1500 California schoolchildren with IQ scores over 135. Terman’s high-

Recent studies have followed the lives of precocious youths who had aced the math SAT at age 13—

One of psychology’s whiz kids was Jean Piaget, who by age 15 was publishing scientific articles on mollusks and who went on to become the twentieth century’s most famous developmental psychologist (Hunt, 1993). Children with extraordinary academic gifts are sometimes more isolated, shy, and in their own worlds (Winner, 2000). But most thrive.