28.1 Twin and Adoption Studies

28-

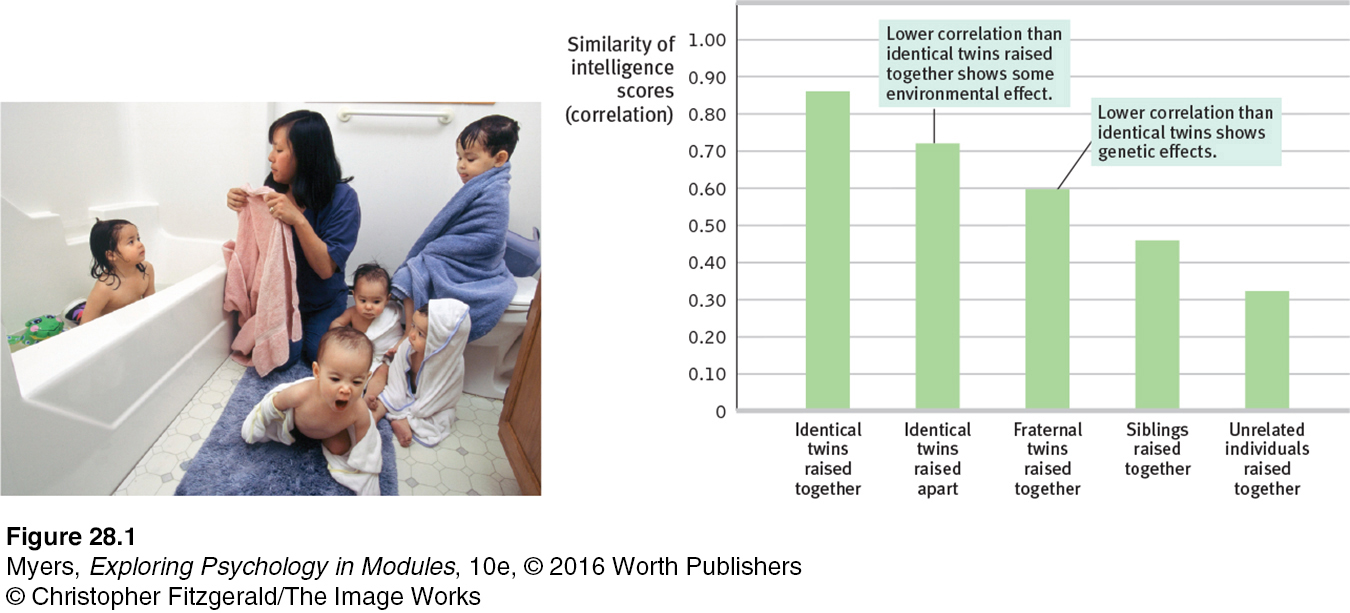

Do people who share the same genes also share mental abilities? As you can see from FIGURE 28.1, which summarizes many studies, the answer is clearly Yes.

heritability the proportion of variation among individuals that we can attribute to genes. The heritability of a trait may vary, depending on the range of populations and environments studied.

Identical twins who grow up together have intelligence test scores nearly as similar as those of the same person taking the same test twice (Haworth et al., 2009; Lykken, 1999). (Fraternal twins, who typically share only half their genes, differ more.) Even when identical twins are adopted by two different families, their scores are very similar. Estimates of the heritability of intelligence—

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

Scans of identical twins’ brains reveal that gray-

Although genes matter, there is no known “genius” gene. One worldwide team of more than 200 researchers pooled their data on the DNA and schooling of 126,559 people (Rietveld et al., 2013). No single DNA segment was more than a minuscule predictor of years of schooling. Together, all the genetic variations they examined accounted for only about 2 percent of the schooling differences. The gene sleuthing continues, but this much seems clear: Intelligence is polygenetic, involving many genes (Bouchard, 2014). Wendy Johnson (2010) likens it to height: 54 specific gene variations together have accounted for 5 percent of our individual differences in height, leaving the rest yet to be explained.

Where environments vary widely, as they do among children of less-

Adoption studies help us assess the influence of environment. Consider:

Adoption of mistreated or neglected children enhances their intelligence scores (van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2005, 2006). So does adoption from poverty into middle-

class homes (Nisbett et al., 2012). In one large Swedish study, children adopted into families with higher socioeconomic status and more educated parents had IQ scores averaging 4.4 points higher than their not- adopted biological siblings (Kendler et al., 2015). The intelligence scores of “virtual twins”—same-

age, unrelated siblings adopted as infants and raised together— correlate +.28 (Segal et al., 2012). This suggests a modest influence of their shared environment.

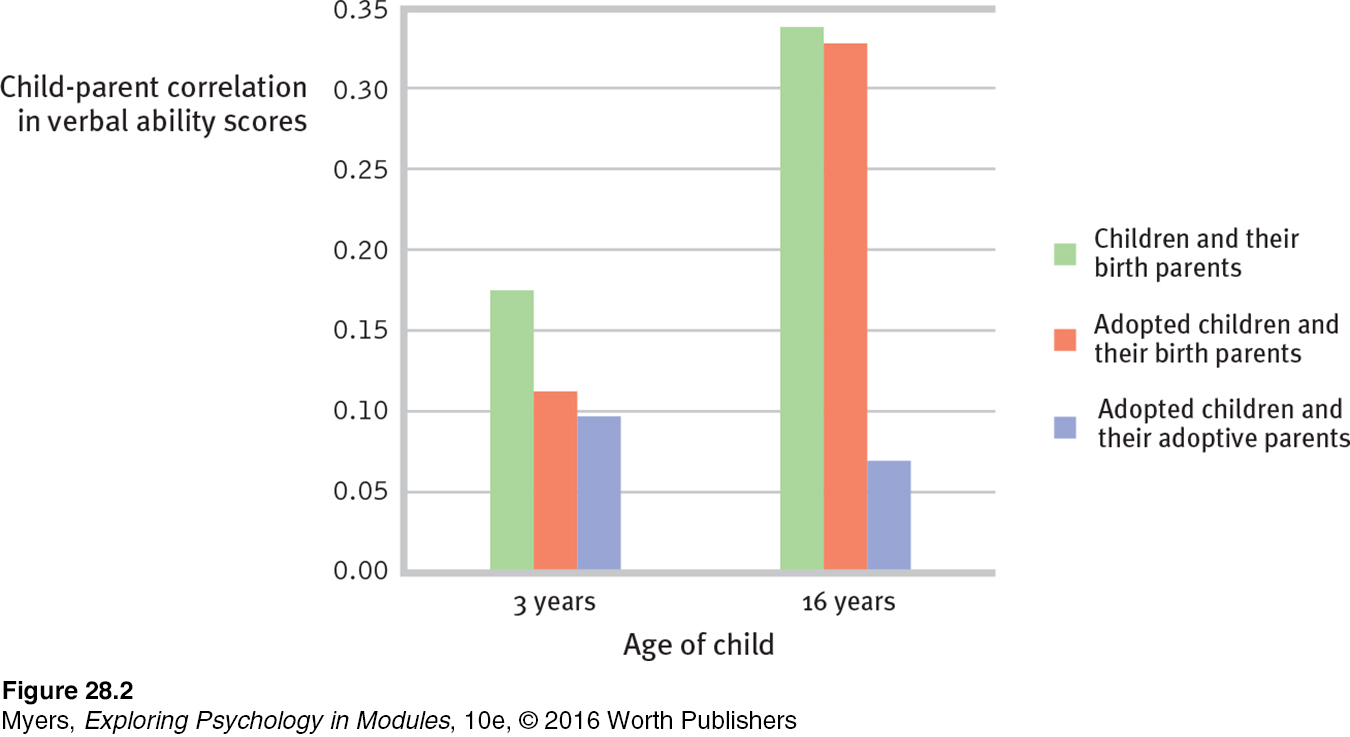

Seeking to untangle genes and environment, researchers have also compared the intelligence test scores of adopted children with those of their family members. These include (a) their biological parents (the providers of their genes) and (b) their adoptive parents (the providers of their home environment). What do you think happens as the years go by and adopted children settle in with their adoptive families? Would you expect the family-

If you said Yes, behavior geneticists have a stunning surprise for you. Mental similarities between adopted children and their adoptive families lessen with age, dropping to roughly zero by adulthood (McGue et al., 1993). Genetic influences—

RETRIEVE IT

Question 9.22

A check on your understanding of heritability: If environments become more equal, the heritability of intelligence will

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |