25.3 Forming Good and Bad Decisions and Judgments

25-

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

When making each day’s hundreds of judgments and decisions (Should I take a jacket? Can I trust this person? Should I shoot the basketball or pass to the player who’s hot?), we seldom take the time and effort to reason systematically. We just follow our intuition—our fast, automatic, unreasoned feelings and thoughts. After interviewing policy makers in government, business, and education, social psychologist Irving Janis (1986) concluded that they “often do not use a reflective problem-

The Availability Heuristic

availability heuristic estimating the likelihood of events based on their availability in memory; if instances come readily to mind (perhaps because of their vividness), we presume such events are common.

When we need to act quickly, the mental shortcuts we call heuristics enable snap judgments. Thanks to our mind’s automatic information processing, intuitive judgments are instantaneous. They also are usually effective (Gigerenzer & Sturm, 2012). However, research by cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) showed how these generally helpful shortcuts can lead even the smartest people into dumb decisions.3 The availability heuristic operates when we estimate the likelihood of events based on how mentally available they are—

“Kahneman and his colleagues and students have changed the way we think about the way people think.”

American Psychological Association President Sharon Brehm, 2007

The availability heuristic colors our judgments of other people, too. Anything that makes information pop into mind—

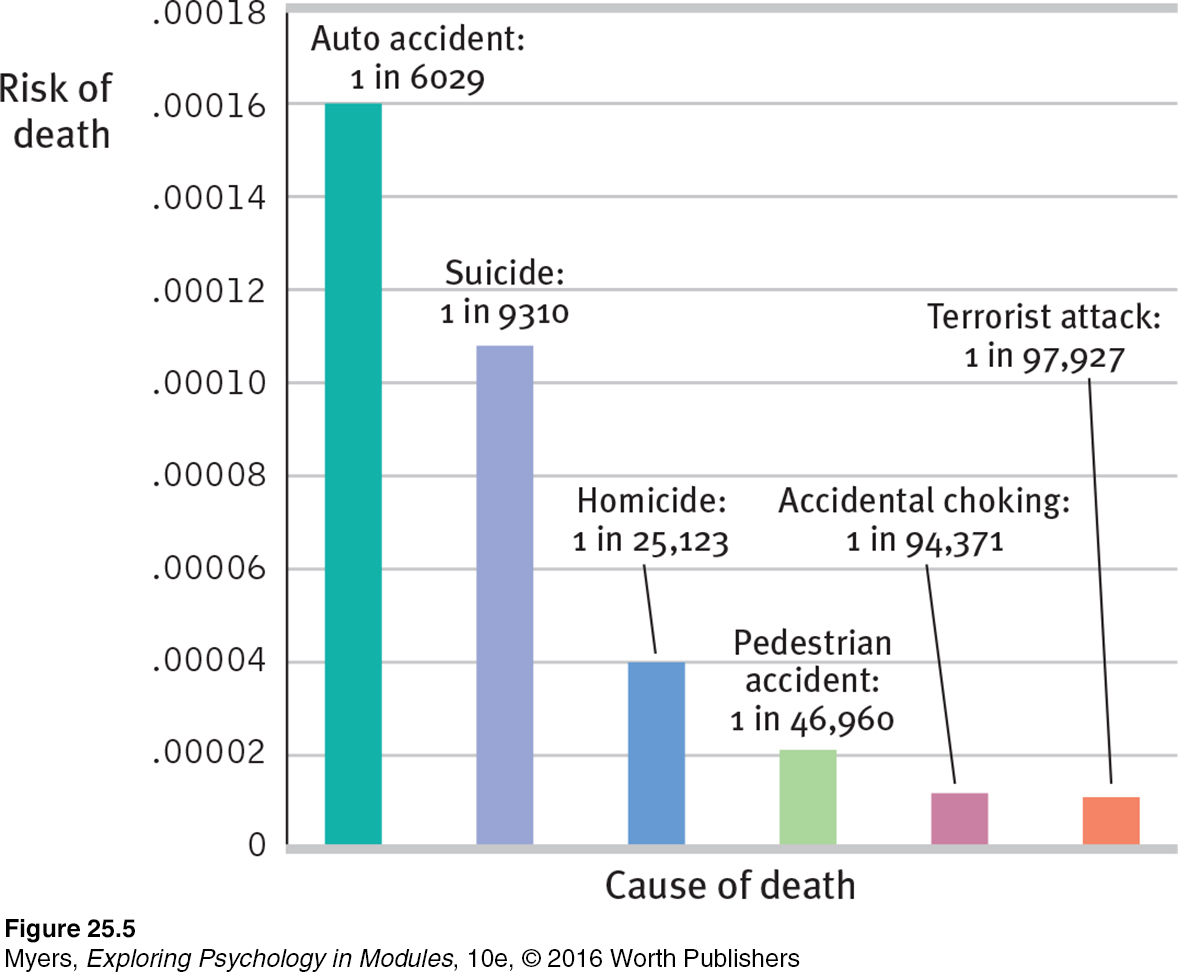

Even during that horrific year, terrorist acts claimed comparatively few lives. Yet when the statistical reality of greater dangers (see FIGURE 25.5) was pitted against the 9/11 terror, the memorable case won: Emotion-

Although our fears often protect us, we sometimes fear the wrong things. (See Thinking Critically About: The Fear Factor below.) We fear flying because we visualize air disasters. We fear letting our sons and daughters walk to school because we see mental snapshots of abducted and brutalized children. We fear swimming in ocean waters because we replay Jaws with ourselves as victims. Even passing by a person who sneezes and coughs can heighten our perceptions of various health risks (Lee et al., 2010). And so, thanks to such readily available images, we come to fear extremely rare events.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Fear Factor—

25-

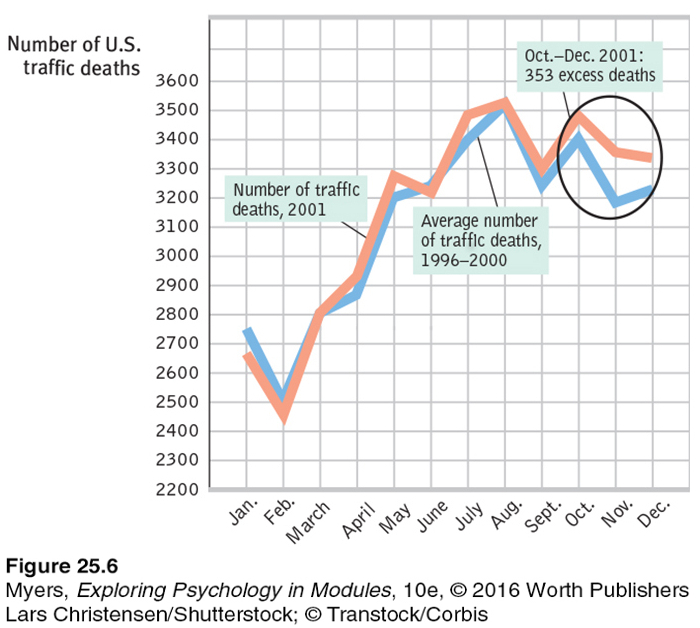

After the 9/11 attacks, many people feared flying more than driving. In a 2006 Gallup survey, only 40 percent of Americans reported being “not afraid at all” to fly. Yet from 2009 to 2011, Americans were—

In a late 2001 essay, I [DM] calculated that if—

Why do we in so many ways fear the wrong things? Why do so many American parents fear school shootings, when their child is more likely to be killed by lightning (Ripley, 2013)? Why, in 2014, were so many Americans more frightened of Ebola (which killed no one who contracted it in the United States) than of influenza, which kills some 24,000 Americans annually? Psychologists have identified four influences that feed fear and cause us to ignore higher risks:

We fear what our ancestral history has prepared us to fear. Human emotions were road tested in the Stone Age. Our old brain prepares us to fear yesterday’s risks: snakes, lizards, and spiders (which combined now kill a tiny fraction of the number killed by modern-

day threats, such as cars and cigarettes). Yesterday’s risks also prepare us to fear confinement and heights, and therefore flying.

We fear what we cannot control. Driving we control; flying we do not.

We fear what is immediate. The dangers of flying are mostly telescoped into the moments of takeoff and landing. The dangers of driving are diffused across many moments, each trivially dangerous.

Thanks to the availability heuristic, we fear what is most readily available in memory. Vivid images, like that of a horrific air crash, feed our judgments of risk. Shark attacks kill about one American per year, while heart disease kills 800,000—

but it’s much easier to visualize a shark bite, and thus many people fear sharks more than cigarettes or the effects of an unhealthy diet (Daley, 2011). Similarly, we remember (and fear) widespread disasters (hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes) that kill people dramatically, in bunches. But we fear too little the less dramatic threats that claim lives quietly, one by one, continuing into the distant future. Horrified citizens and commentators renewed calls for U.S. gun control in 2015, after nine African- Americans at a Bible study were slain by a racist guest— although guns kill about 30 Americans every day, one by one, in a less dramatic fashion. Philanthropist Bill Gates has noted that each year, a half- million children worldwide die from rotavirus. This is the equivalent of four 747s full of children every day, and we hear nothing of it (Glass, 2004). Media outlets often draw readers and viewers by reporting on the immediate and the dramatic. “If it bleeds, it leads.”

The news, and our own memorable experiences, can make us disproportionately fearful of infinitesimal risks—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why can news be described as “something that hardly ever happens”? How does knowing this help us assess our fears?

“Fearful people are more dependent, more easily manipulated and controlled, more susceptible to deceptively simple, strong, tough measures and hard-

Media researcher George Gerbner to U.S. Congressional Subcommittee on Communications, 1981

Meanwhile, the lack of available images of future climate change disasters—

"Don’t believe everything you think."

Bumper sticker

“Global warming isn’t real because it was cold today! Also great news: World hunger is over because I just ate.”

Stephen Colbert tweet, November 18, 2014

Dramatic outcomes make us gasp; probabilities we hardly grasp. As of 2013, some 40 nations have sought to harness the positive power of vivid, memorable images by putting eye-

Overconfidence

overconfidence the tendency to be more confident than correct—

Sometimes our judgments and decisions go awry simply because we are more confident than correct. Across various tasks, people overestimate their performance (Metcalfe, 1998). If 60 percent of people correctly answer a factual question, such as “Is absinthe a liqueur or a precious stone?,” they will typically average 75 percent confidence (Fischhoff et al., 1977). (It’s a licorice-

It was an overconfident BP that, before its exploded drilling platform spewed oil into the Gulf of Mexico, downplayed safety concerns, and then downplayed the spill’s magnitude (Mohr et al., 2010; Urbina, 2010). It is overconfidence that drives stockbrokers and investment managers to market their ability to outperform stock market averages (Malkiel, 2012). A purchase of stock X, recommended by a broker who judges this to be the time to buy, is usually balanced by a sale made by someone who judges this to be the time to sell. Despite their confidence, buyer and seller cannot both be right.

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, 1979

“When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it; this is knowledge.”

Confucius (551–

Overconfidence can also feed extreme political views. People with a superficial understanding of proposals for cap-

Classrooms are full of overconfident students who expect to finish assignments and write papers ahead of schedule (Buehler et al., 1994, 2002). In fact, these projects generally take about twice the number of days predicted. This “planning fallacy” (underestimating the time and cost of a project) routinely occurs with construction projects, which often finish late and over budget.

Overconfidence can have adaptive value. People who err on the side of overconfidence live more happily. Their seeming competence can help them gain influence (Anderson et al., 2012). Moreover, given prompt and clear feedback, as weather forecasters receive after each day’s predictions, we can learn to be more realistic about the accuracy of our judgments (Fischhoff, 1982). The wisdom to know when we know a thing and when we do not is born of experience.

Belief Perseverance

belief perseverance clinging to one’s initial conceptions after the basis on which they were formed has been discredited.

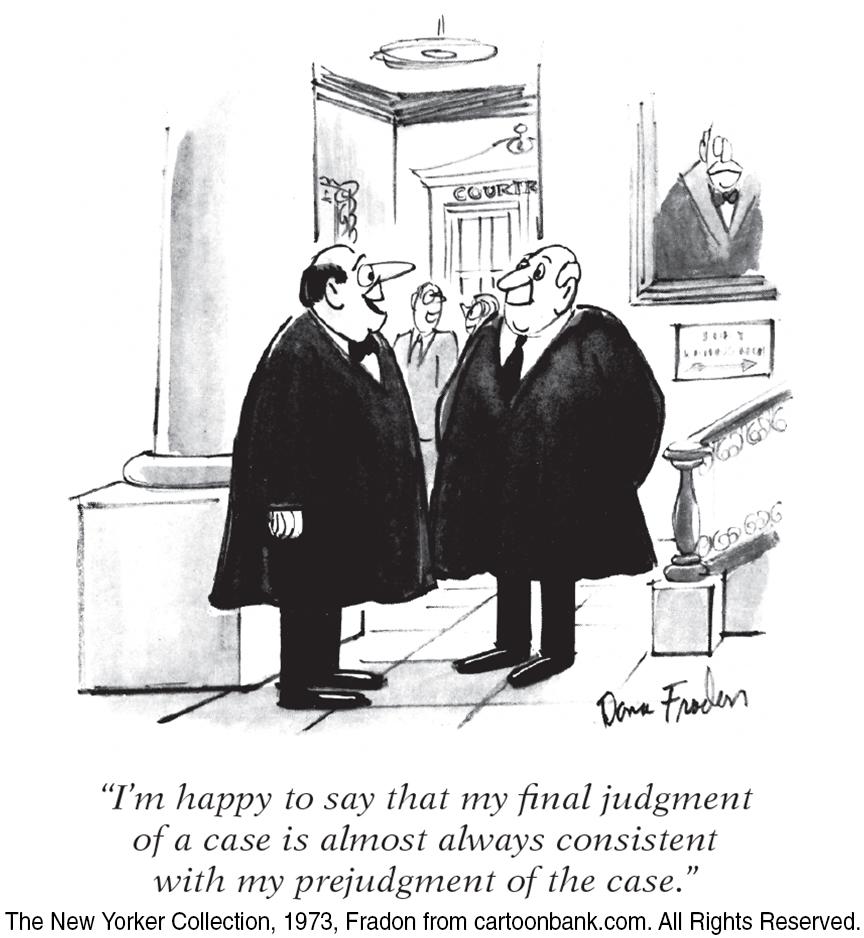

Our overconfidence is startling. Equally so is our belief perseverance—our tendency to cling to our beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. One study of belief perseverance engaged people with opposing views of capital punishment (Lord et al., 1979). After studying two supposedly new research findings, one supporting and the other refuting the claim that the death penalty deters crime, each side was more impressed by the study supporting its own beliefs. And each readily disputed the other study. Thus, showing the pro-

To rein in belief perseverance, a simple remedy exists: Consider the opposite. When the same researchers repeated the capital-

The more we come to appreciate why our beliefs might be true, the more tightly we cling to them. Once beliefs form and get justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. Prejudice persists. Beliefs often persevere.

The Effects of Framing

framing the way an issue is posed; how an issue is framed can significantly affect decisions and judgments.

Framing—the way we present an issue—

Framing can be a powerful persuasion tool. Carefully posed options can nudge people toward decisions that could benefit them or society as a whole (Benartzi & Thaler, 2013; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008):

Encouraging citizens to be organ donors. In many European countries as well as the United States, those renewing their driver’s license can decide whether they want to be organ donors. In some countries, the default option is Yes, but people can opt out. Nearly 100 percent of the people in opt-

out countries have agreed to be donors. In the United States, Britain, and Germany, the default option is No, but people can opt in. In these countries, less than half have agreed to be donors (Hajhosseini et al., 2013; Johnson & Goldstein, 2003). Nudging employees to save for their retirement. A 2006 U.S. pension law recognized the framing effect. Before that law, employees who wanted to contribute to a retirement plan typically had to choose a lower take-

home pay, which few people will do. Companies can now automatically enroll their employees in the plan but allow them to opt out. Under the new voluntary opt- out arrangement, enrollments in one analysis of 3.4 million workers soared from 59 to 86 percent (Rosenberg, 2010). Boosting student morale: When 70 percent on an exam feels better than 72 percent. One economist’s students were upset by a “hard” exam, on which they averaged 72 out of 100. So on the next exam, he made the highest possible score 137 points. Although the class average score of 96 was only 70 percent correct, “the students were delighted” (a numerical 96 felt so much better than 72). So he continued the reframed exam results thereafter (Thaler, 2015).

The point to remember: Those who understand the power of framing can use it (for good or ill) to nudge our decisions.

The Perils and Powers of Intuition

25-

The perils of intuition—

Throughout this book you will see examples of smart intuition. In brief,

Intuition is analysis “frozen into habit” (Simon, 2001). It is implicit knowledge—

what we’ve learned and recorded in our brains but can’t fully explain (Chassy & Gobet, 2011; Gore & Sadler- Smith, 2011). Chess masters display this tacit expertise in “blitz chess,” where, after barely a glance, they intuitively know the right move (Burns, 2004). We see this expertise in the smart and quick judgments of experienced nurses, firefighters, art critics, car mechanics, and musicians. Skilled athletes can react without thinking. Indeed, conscious thinking may disrupt well- practiced movements such as batting or shooting free throws. For all of us who have developed some special skill, what feels like instant intuition is actually an acquired ability to perceive and react in an eyeblink. Intuition is usually adaptive, enabling quick reactions. Our fast and frugal heuristics let us intuitively assume that fuzzy looking objects are far away—

which they usually are, except on foggy mornings. Seeing a stranger who looks like someone who has harmed or threatened us in the past, we may automatically react warily. Newlyweds’ automatic associations— their gut reactions— to their new spouses likewise predict their future marital happiness (McNulty et al., 2013). Our learned associations surface as gut feelings. Page 324Intuition flows from unconscious processing. Today’s cognitive science offers many examples of unconscious automatic influences on our judgments (Custers & Aarts, 2010). Consider: Most people guess that the more complex the choice, the smarter it is to make decisions rationally rather than intuitively (Inbar et al., 2010). Actually, Dutch psychologists have shown that in making complex decisions, we benefit by letting our brain work on a problem without consciously thinking about it (Strick et al., 2010, 2011). In one series of experiments, three groups of people read complex information (for example, about apartments or soccer matches). The first group’s participants stated their preference immediately after reading information about four possible options. The second group, given several minutes to analyze the information, made slightly smarter decisions. But wisest of all, in several studies, was the third group, whose attention was distracted for a time, enabling their minds to engage in automatic, unconscious processing of the complex information. The practical lesson: Letting a problem “incubate” while we attend to other things can pay dividends (Sio & Ormerod, 2009). Facing a difficult decision involving lots of facts, we’re wise to gather all the information we can, and then say, “Give me some time not to think about this.” By taking time to sleep on it, we let our unconscious mental machinery work. Thanks to our active brain, nonconscious thinking (reasoning, problem solving, decision making, planning) is surprisingly astute (Creswell et al., 2013; Hassin, 2013; Lin & Murray, 2015).

Critics note that some studies have not found the supposed power of unconscious thought and remind us that deliberate, conscious thought also furthers smart thinking (Lassiter et al., 2009; Newell, 2015; Nieuwenstein et al., 2015; Payne et al., 2008). In challenging situations, superior decision makers, including chess players, take time to think (Moxley et al., 2012). And with many sorts of problems, deliberative thinkers are aware of the intuitive option, but know when to override it (Mata et al., 2013). Consider:

A bat and a ball together cost 110 cents.

The bat costs 100 cents more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

Most people’s intuitive response—

The bottom line: Our two-