12.2 12.1 Narrowing the Field through the Primary Process

The first phase of a presidential election year begins in January, when Democratic and Republican candidates seek their party’s nomination for president by running in state caucuses and primaries. Caucuses and primaries are a series of political events used by the Democratic and Republican parties to determine their nominees for president. The first caucus of the election season is held in Iowa. Voters from Iowa’s precincts assemble in a public place to discuss the candidates and to select representatives to attend county conventions. The process builds through conventions at the county, congressional district, and state levels. In comparison, primaries are statewide elections. Candidates earn delegate votes based on the number of voters who support them at the caucuses’ conventions and primaries. The primary season concludes with a party convention, where a candidate becomes the party’s nominee if he or she has received a majority of the delegate votes from the primary season. If no candidate has a simple majority, then the convention is called brokered and the party’s nominee is determined through a negotiation process.

That Iowa is the first caucus of the primary season seems to have been an accident, but it is now written into the parties’ rules. The winner of the Iowa caucus achieves a sort of front-runner status that translates into greater opportunities to raise funds to support his or her campaign. Other states have tried to jockey for position so that their caucus or primary appears earlier in the primary season and, hence, has greater impact. Delegate counts have been discounted when a state has pushed its primary before the Iowa caucus, as both Florida and Michigan did in the 2008 Democratic primary.

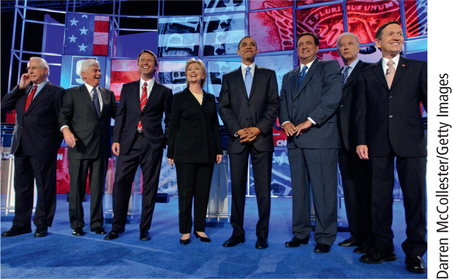

There is some variability in how delegates are awarded for the Republican caucuses and primaries. We will return to their most frequently used rule from the 2008 Republican primary after we examine how delegates are tallied in the Democratic primaries. The same Democratic Delegate Selection Rules are used for all primaries to translate votes into delegate counts. The 2008 Democratic primary was one of the closest primaries in recent U.S. history, second only to the 1976 Republican contest between Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan that was not decided until the convention. The close 2008 race between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton was due in part to the Democratic Party rules that assign delegates to each candidate based on his or her proportion of the popular vote. Although these rules assign delegates based on the number of votes each candidate receives, these rules prevent candidates who do not receive 15% of the popular vote from receiving any delegates. As such, these rules help narrow the field of candidates. For example, of the eight candidates who mounted national campaigns in the 2008 Democratic primary, only three were awarded delegates.

Because delegates are individuals and cannot be divided into fractions, awarding delegates proportionally requires a systematic way of rounding the fractional values to whole numbers. Methods for doing so, referred to as apportionment methods, are best known for their role in determining the number of representatives allotted to each state in the U.S. House of Representatives (see Chapter 14). The Democratic Delegate Selection Rules appear in Table 12.1. Example 1 demonstrates the five steps.

| Step 1. | Tabulate the percentage of the vote that each presidential preference (including uncommitted status) receives in the congressional district to three decimals. |

| Step 2. | Retabulate the percentage of the vote to three decimals, received by each presidential preference, excluding the votes of presidential preferences whose percentage in Step 1 falls below 15%. |

| Step 3. | Multiply the number of delegates to be allocated by the percentage received by each presidential preference. |

| Step 4. | Delegates shall be allocated to each presidential preference based on the whole numbers which result from the multiplication in Step 3. |

| Step 5. | Remaining delegates, if any, shall be awarded in order of the highest fractional remainders in Step 3. |

EXAMPLE 1 Proportionally Awarding Delegates in the Democratic Primary

Proportionally Awarding Delegates in the Democratic Primary

The New Hampshire primary is the first primary after the Iowa caucuses. For the 2008 Democratic primary, New Hampshire was divided into two districts, each with seven delegates. Of the 21 candidates who received votes in District 2, the top five vote getters were Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, Dennis Kucinich, Barack Obama, and Bill Richardson. Their vote totals are listed in Table 12.2, and all other candidates who received votes are bundled together under “Others.”

The columns of Table 12.2 demonstrate the steps outlined in the Democratic Delegate Selection Rules (Table 12.1). Following Step 1, the first column contains the percentage of the popular vote for the candidates. For example, Clinton’s percentage of the popular vote is the total number of votes she received (55,418) divided by the total number of votes (146,871); hence, her percentage is 55,418/146,871 ≈0.37743 =37.743%. As described in Step 2, all candidates that receive less than 15% of the popular vote are eliminated; these are Kucinich, Richardson, and the candidates collected under the category “Others.” The percentages of the remaining candidates—Clinton, Edwards, and Obama—are adjusted accordingly. This is achieved by discarding the votes for all candidates that failed to meet the 15% threshold. For example, Clinton’s adjusted percentage becomes 40.602 by calculating 55,418/136,490≈40.602%.

| Candidates | Popular Votes |

Percentage of Votes |

Adjusted Votes |

Adjusted Percentage |

Quota | Initial Delegates |

Final Delegates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hillary Clinton | 55,418 | 37.732 | 55,418 | 40.602 | 2.8421 | 2 | 3 |

| John Edwards | 25,224 | 17.174 | 25,224 | 18.48 | 1.1936 | 1 | 1 |

| Dennis Kucinich | 2,176 | 1.482 | |||||

| Barack Obama | 55,848 | 38.025 | 55,848 | 40.917 | 2.8642 | 2 | 3 |

| Bill Richardson | 7,220 | 4.916 | |||||

| Others | 985 | 0.671 | |||||

| Totals | 146,871 | 100 | 136,490 | 100 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

Steps 3 to 5 are usually referred to as Hamilton’s method, a method of apportionment attributed to U.S. founding father Alexander Hamilton. In Step 3, the remaining candidates’ adjusted percentages are multiplied by 7, the total number of delegates to be awarded in District 2, to calculate their quotas—the proportion of the delegates the candidate should receive given his or her adjusted percentage of the vote. For instance, Clinton’s quota of 2.8421 satisfies 40.602%×7 =0.40602×7 =2.8421.

In Step 4, the quotas are rounded down to give an initial apportionment of 2, 1, and 2 delegates, respectively, for Clinton, Edwards, and Obama. For example, Clinton’s quota of 2.8421 is rounded down to 2. As a consequence, Step 4 awards the first 5(=2+1+2) delegates, meaning that there are 2 delegates left to allocate. In Step 5, the remaining 2 delegates are awarded to the candidates with the largest fractional/decimal remainders. Obama has the largest decimal remainder of 2.8652−2=0.8652. Clinton’s remainder is the second highest. It follows that both Obama and Clinton receive an extra delegate, rounding their delegate totals to 3 each. The final delegate counts for District 2 of the 2008 New Hampshire Democratic primary are 3 delegates each to Clinton and Obama and 1 delegate to Edwards.

Self Check 1

How was Obama’s adjusted percentage in Table 12.2 calculated?

- Obama’s adjusted percentage is 55,848/136,490. The numerator 55,848 is the number of votes Obama received. The denominator 136,490 is the sum of the votes cast for candidates that receive at least 15% of the votes.

The proportional allocation of delegates in the Democratic primary is in contrast to the most frequently used rule from the 2008 Republican primary: the winner-take-all strategy. As the name implies, under this strategy the candidate that receives the most popular votes receives all of the delegates. The 2008 Democratic primary was not decided until June, whereas John McCain had wrapped up the 2008 Republican nomination on March 4. The reason for the difference in how long it takes a candidate to lock down the nomination could be that the winner-take-all strategy focuses attention on the first-place candidate. The candidates that win early primaries also receive the additional campaign funds that come with the increased media attention and popular support. The effect is that the candidate field narrows more quickly in the Republican primary than in the Democratic primary. Also, the shorter time it takes for the Republican Party to determine their presidential nominee can be viewed as advantageous, as it gives the Republican candidate more time to focus on the potential Democratic opponent for the general election in the fall.

When data are rounded, unusual behavior or a counterintuitive result may be observed. Such behavior is referred to as a paradox in the apportionment literature (see Chapter 14). Requiring candidates to receive 15% of the total vote to be awarded a delegate introduces surprising behavior that can affect even the non-eliminated candidates in ways that are not predictable. It may seem that eliminating candidates who receive less than 15% of the vote can only help the remaining candidates by giving them more delegate votes. The following example shows that this may not always be the case.

EXAMPLE 2 Paradoxical Behavior Under the Democratic Delegate Selection Rules

Paradoxical Behavior Under the Democratic Delegate Selection Rules

Suppose that the Democratic Delegate Selection Rules are used to allocate five delegates in a district for vote totals given in Table 12.3. The application of the rules results in Jones, Umberto, and Viktor receiving 4, 1, and 0 delegates, respectively. If the election official forgets to drop Viktor for receiving less than 15% of the vote and instead uses Steps 3 to 5 on the original/non-adjusted data, then the outcome changes, as given in Table 12.4: Jones now receives 3 delegates and Umberto receives 2. Viktor still fails to receive a single delegate. But how the five delegates are split between Jones and Umberto changes depends on whether or not Viktor’s votes are discarded or not! By eliminating Viktor from consideration by the 15% rule, Umberto’s delegate count decreases from 2 to 1.

| Candidates | Popular Vote |

Percentage of Votes |

Remaining Votes |

Adjusted Percentage |

Quota | Initial Delegates |

Final Delegates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stephen Jones | 6625 | 66.25 | 6625 | 70.479 | 3.524 | 3 | 4 |

| Tracey Umberto | 2775 | 27.75 | 2775 | 29.521 | 1.476 | 1 | 1 |

| George Viktor | 600 | 6 | |||||

| Totals | 10,000 | 100 | 9400 | 100 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Candidates | Popular Vote |

Percentage of Votes |

Quota | Initial Delegates |

Final Delegates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stephen Jones | 6625 | 66.25 | 3.313 | 3 | 3 |

| Tracey Umberto | 2775 | 27.75 | 1.387 | 1 | 2 |

| George Viktor | 600 | 6 | 0.300 | ||

| Totals | 10,000 | 100 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

Self Check 2

How is Stephen Jones’s adjusted quota determined in Table 12.3?

- Stephen Jones’s adjusted quota 3.524 is the adjusted percentage 70.479% times 5 delegates.

Despite the paradoxical behavior that can occur under the Democratic Delegate Selection Rules, the 15 % threshold achieves its goal of narrowing the field by keeping weakly supported candidates from being allocated any delegates. For states with few delegates, a candidate with less than 15% of the vote may not receive any delegates in a district anyway, but that is not the case for states with many delegates. And even states with small districts use the same apportionment method with 15% threshold to allocate Pledged Party Leaders and Elected Officials (or PLEO) delegates and at-large delegates using the statewide vote totals for the candidates. The number of these additional delegates usually surpasses the number allocated in any one district.

The multi-stream calculation of delegate totals is part of the Rube Goldberg aspect of the primary process. As discussed, the winner-take-all policy used in the Republican primaries consolidates support more quickly for a single candidate. After the two party conventions, the Democratic and Republican nominees and any third party candidates square off in the general election. How candidates position themselves in the general election is discussed in the next section. These strategic implications are also useful in explaining how candidates compete strategically in the primary elections.