1 WTO Goals on Agricultural Export Subsidies

Describes agreements made at the meeting of the WTO in Hong Kong 2005, but never ratified.

1. Agricultural Export Subsidies

WTO agreed to abolish all agricultural export subsidies by 2013. However, Europe and the U.S. maintain generous agricultural subsidies.

a. Indirect Subsidies

The WTO agreed to eliminate indirect subsidies to agriculture, including food aid to developing countries. Europe has eliminated its food aid programs, and now gives cash aid instead; the U.S. still provides food aid. This chapter will assess the debate over cash versus food aid.

b. Domestic Farm Supports

WTO also wants to tackle other supports to agriculture that are not specifically targeted on exports.

c. Cotton Subsidies

U.S. cotton subsidies are particularly threatening to African countries that export cotton. The U.S. agreed to eliminate them, but the agreement has not been ratified.

2. Other Matters from the Hong Kong WTO Meeting

a. Tariffs in Agriculture

Contentious issue: the use of tariffs in response to the use of agricultural subsidies by other countries. This ended the meeting in Geneva in 2008, and leaves the future of the Doha round in doubt.

b. Issues Involving Trade in Industrial Goods and Services

Other issues discussed in Hong Kong: (1) further reductions in industrial tariffs; (2) opening trade in services; (3) agreement not to impose any duties or tariffs on products from the poorest countries.

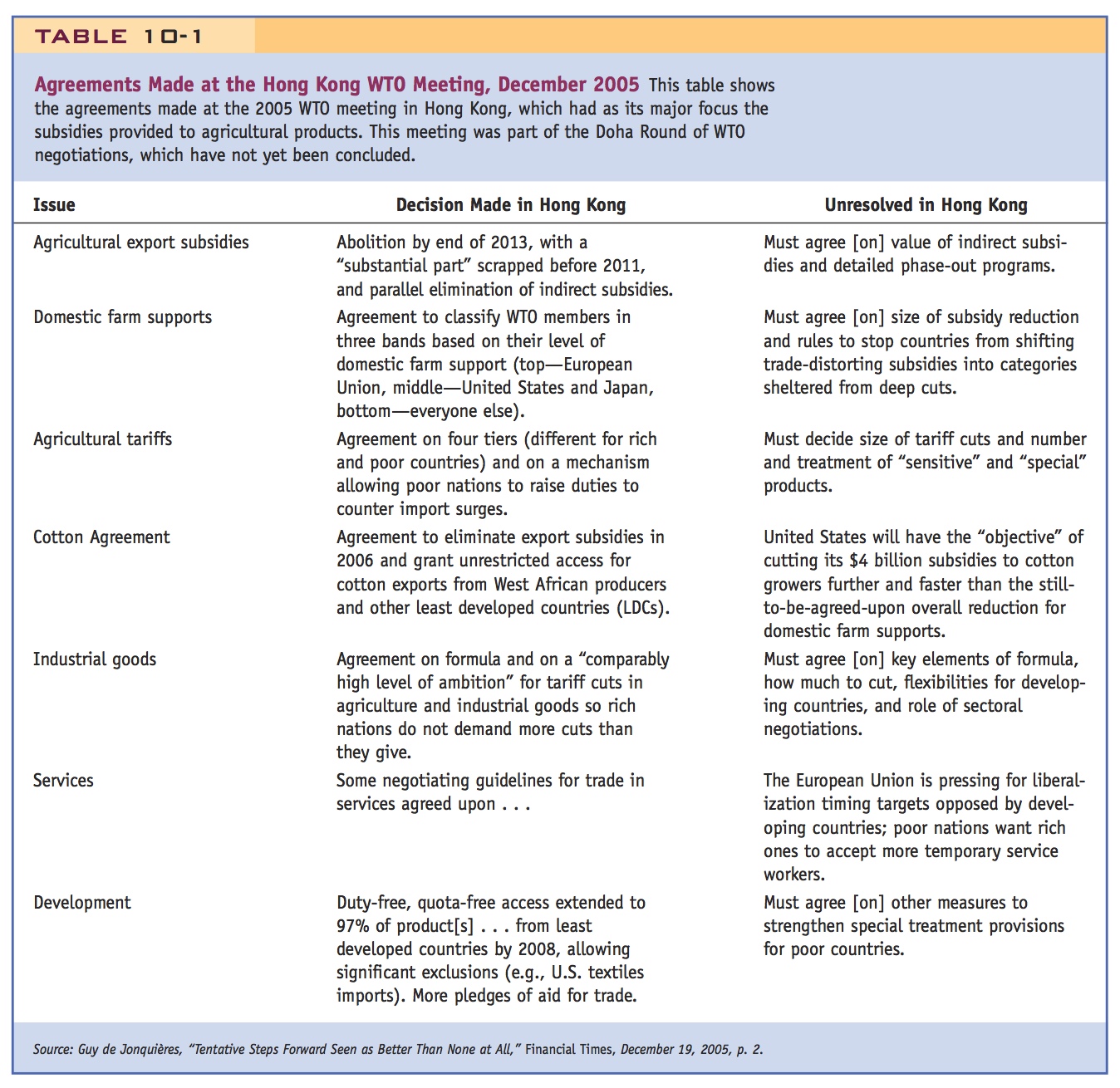

In Table 10-1, we describe the agreements made at the Hong Kong meeting of the WTO in December 2005. These agreements were never ratified by the legislatures in the countries involved, however, so it is best to think of them as goals that have not yet been achieved rather than definite outcomes. Four of the items deal with agricultural subsidies and tariffs, which were the focus of that meeting.

Agricultural Export Subsidies

Emphasize the divergent interests of the U.S. and the EU, on the one hand, and the agricultural exporters.

An export subsidy is payment to firms for every unit exported (either a fixed amount or a fraction of the sales price). Governments give subsidies to encourage domestic firms to produce more in particular industries. As shown in Table 10-1, the member countries of the WTO agreed to abolish all export subsidies in agriculture by the end of 2013, though as mentioned above, this goal has not yet been achieved. Some agricultural exporters, such as Brazil, India, and China, had pushed for an earlier end to the subsidies but faced stiff opposition from many European countries. Europe maintains a system of agricultural subsidies known as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). For example, to help its sugar growers, the CAP pays farmers up to 50 euros per ton of harvested sugar beets, which is five times the world market price. Because of the subsidy, European farmers can afford to sell the sugar made from their sugar beets at a much lower price than the world market price. As a result, the sugar beet subsidy makes Europe a leading supplier of sugar worldwide, even though countries in more temperate or tropical climates have a natural comparative advantage. Other countries maintain agricultural subsidies that are just as generous. The United States, for example, pays cotton farmers to grow more cotton and then subsidizes agribusiness and manufacturers to buy the American cotton, so both the production and the sale of cotton receive subsidies. Japan allows 10% of the approximately 7 million tons of milled rice it consumes annually to enter into the country tariff-free but imposes a 500% tariff on any rice in excess of this 10% limit. There are many other examples of agricultural protection like this from countries all over the world.

330

Emphasize here too, except that the EU has already eliminated food aid and the U.S. is still refusing to.

Indirect Subsidies Included in the Hong Kong export subsidy agreement is the parallel elimination of indirect subsidies to agriculture, including food aid from developed to poor countries and other exports by state-sponsored trading companies in advanced countries. Europe has already eliminated its food aid subsidies and argues that cash aid to poor countries is much more effective; the United States continues to export agricultural commodities as aid. Later in the chapter, we explore the argument made by the European Union that cash aid is more effective than food aid in assisting developing countries.

Domestic Farm Supports Another item mentioned in the Hong Kong agreement is domestic farm supports, which refers to any assistance given to farmers, even if it is not directly tied to exports. Such domestic assistance programs can still have an indirect effect on exports by lowering the costs (and hence augmenting the competitiveness) of domestic products. The Hong Kong agreement is only a first step toward classifying the extent of such programs in each country, without any firm commitment as to when they might be eliminated.

Cotton Subsidies Finally, export subsidies in cotton received special attention because that crop is exported by many low-income African countries and is highly subsidized in the United States. The United States agreed to eliminate these export subsidies, but that action has not yet occurred because the Hong Kong agreement was never ratified. Subsidies to the cotton industry remain a contentious issue between the United States and other exporting countries, such as Brazil.

Other Matters from the Hong Kong WTO Meeting

Issues that are related to export subsidies were also discussed at the 2005 Hong Kong meeting, in addition to the elimination of the subsidies themselves. One of these issues is the use of tariffs as a response to other countries’ use of subsidies. As we now explain, that issue is so contentious that it led to the breakup of the subsequent meeting in Geneva in 2008 and threatens to derail the Doha Round of negotiations.

331

Tariffs in Agriculture Export subsidies applied by large countries depress world prices, so that exporting countries can expect tariffs to be imposed on the subsidized products when they are imported by other countries. The agriculture-exporting developing countries pushed for a dramatic reduction in these and other agriculture-related tariffs, especially by importing industrial countries, but were not able to obtain such a commitment in Hong Kong.

These discussions continued three years later in Geneva. At that time, the developing country food importers wanted two special provisions allowing them to limit the amount by which tariffs would be lowered. First, they wanted a list of “special products” that would be completely exempt from tariff reductions. Second, they wanted a “special safeguard mechanism” that could be applied to all other agricultural products. Under this mechanism, tariffs could be temporarily raised whenever imports suddenly rose or their prices suddenly fell.

Recall from Chapter 8 that Article XIX of the GATT allows for such a “safeguard tariff,” and that there are specific rules allowing for its use mainly in manufactured goods (see Side Bar: Key Provisions of the GATT in Chapter 8). The “special safeguard mechanism” in agriculture likewise requires that countries agree on the exact conditions under which it would be used. The problem in Hong Kong was that countries could not agree on the conditions under which a safeguard tariff could be temporarily applied. Likewise, the negotiators at the Geneva meeting could not agree on how many agricultural products could be treated as “special” by the importing countries, and exempt from any tariff cuts. These conflicts led to the breakdown of the Geneva talks in 2008, but must eventually be resolved before the Doha Round of negotiations can be concluded.

Issues Involving Trade in Industrial Goods and Services Other issues were also discussed in Hong Kong, as listed in Table 10-1. To achieve further cuts in the tariffs on industrial goods, there was agreement in principle to use some formula for the cuts, but the exact nature of that formula was left for future negotiation. There was also an agreement to discuss opening trade in service sectors, which would benefit the industrial countries and their large service industries. The developing countries are expected to make some future offers to open their markets to trade in services, but in return they will expect wealthy countries to accept more temporary immigrant workers in their service sectors. Finally, there was agreement to allow 97% of imported products from the world’s 50 least developed countries (LDCs) to enter WTO member markets tariff free and duty free. The United States already allows duty-free and tariff-free access for 83% of products from those 50 countries, and under this agreement, the United States would extend that access to nearly all products. Omitted from this agreement, however, are textile imports into the United States from LDCs because the United States wants to protect its domestic textile producers from low-priced imports from countries such as Bangladesh and Cambodia. This is not surprising, given our discussion of the United States’ sensitivity to low-cost imports in the clothing and textiles industries, as illustrated by the history of quotas on clothing imports (see Chapter 8).