3 Export Subsidies in a Large Home Country

Here too, ask students to compare this to the tariff of a large country.

Now the country is large enough to affect world prices, so the Foreign import demand curve is negatively sloped. The analysis should be compared to that of an import tariff in a large country in Section 4 of Chapter 8.

1. Effect of the Subsidy

The Home export supply curve shifts down. The world price falls, while the Home price increases by less than the subsidy per unit: Home suffers a deterioration of the TOT, so that part of the benefit of the subsidy to Home producers is being shifted to Foreign consumers, who pay a lower price. Exports increase.

a. Home Welfare

As in the small country case, Home consumer surplus decreases, Home producer surplus increases, and the government loses revenues. However, the fall in the TOT also reduces export revenues.

b. Foreign and World Welfare

Home loses, while Foreign gains. However, there is a deadweight loss to the world, caused by the fact that the TOT loss to Home is not perfectly offset by the TOT gain to Foreign.

Could export subsidies be used to transfer wealth from rich to poor countries? Yes, but it would be more efficient to give cash transfers, since they would avoid the deadweight loss of the subsidies.

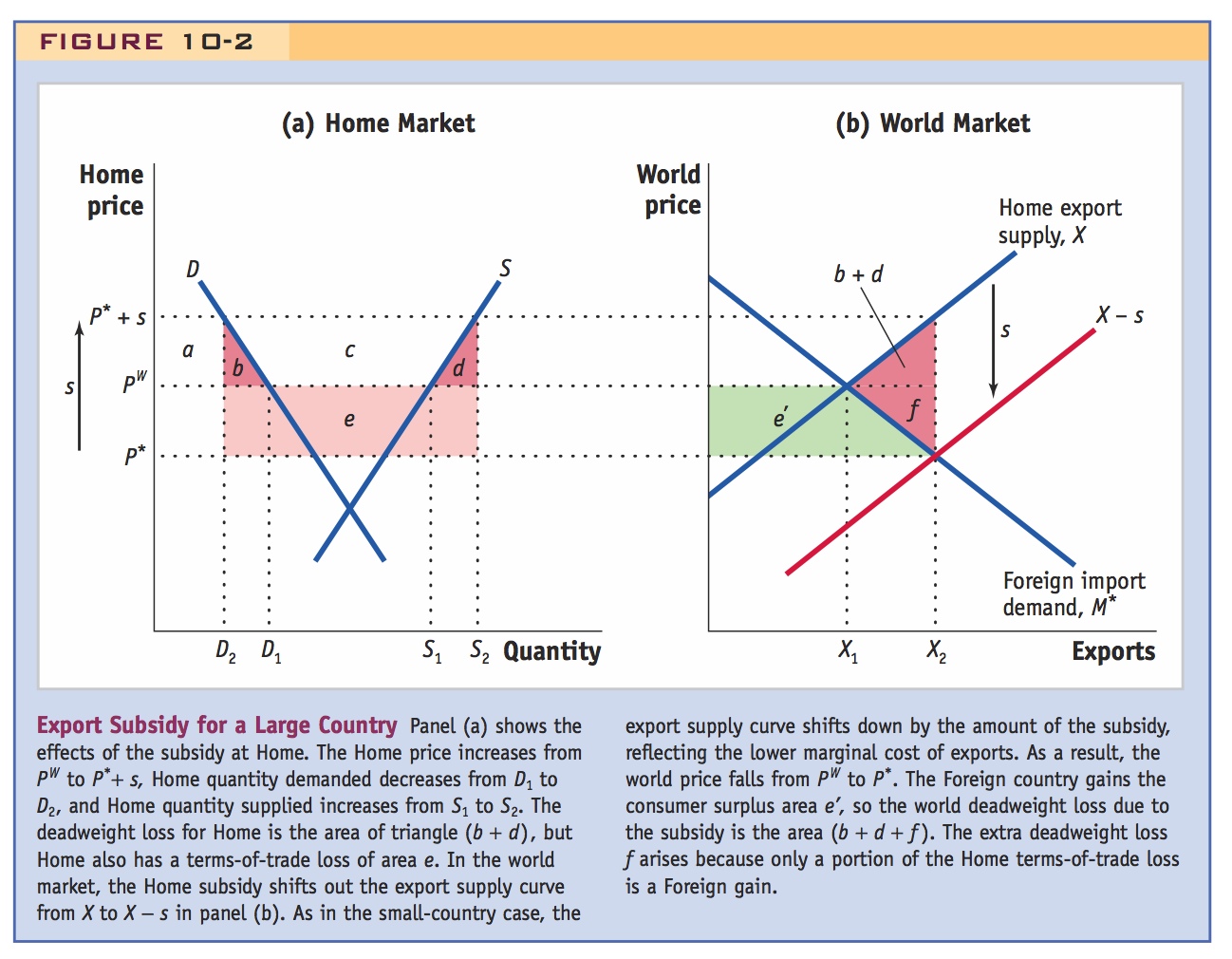

Now suppose that the Home country is a large enough seller on international markets so that its subsidy affects the world price of the sugar (e.g., this occurs with European sugar subsidies and U.S. cotton subsidies). This large-country case is illustrated in Figure 10-2. In panel (b), we draw the Foreign import demand curve M* as downward-sloping because changes in the amount exported, as will occur when Home applies a subsidy, now affect the world price.

Under free trade, the Home and world price is PW. At this price, Home exports X1 = S1 − D1, and the world export market is in equilibrium at the intersection of Home export supply X and Foreign import demand M*. Home and Foreign consumers pay the same price for the good, PW, which is the world price.

Effect of the Subsidy

Suppose that Home applies a subsidy of s dollars per ton of sugar exported. As we found for the small country, a subsidy to Home export production is shown as a downward shift of the Home export supply curve in panel (b) by the amount s; the vertical distance between the original export supply curve X and the new export supply curve X − s is precisely the amount of the subsidy s. The new intersection of Home export supply, X − s, and Foreign import demand M* corresponds to a new world price of P*, decreased from the free-trade world price PW, and a Home price P* + s, increased from the free-trade price PW. Furthermore, the equilibrium with the subsidy now occurs at the export quantity X2 in panel (b), increased from X1.

In Chapter 2, we defined the terms of trade for a country as the ratio of export prices to import prices. Generally, a fall in the terms of trade indicates a loss for a country because it is either receiving less for exports or paying more for imports. We have found that with the export subsidy, Foreign consumers pay a lower price for Home exports, which is therefore a fall in the Home terms of trade but a gain in the Foreign terms of trade. We should expect, therefore, that the Home country will suffer an overall loss because of the subsidy but that Foreign consumers will gain. To confirm these effects, let’s investigate the impact of the subsidy on Home and Foreign welfare.

335

So now there is also a TOT loss.

Home Welfare In panel (a) of Figure 10-2, the increase in the Home price from PW to P* + s reduces consumer surplus by the amount (a + b). In addition, the increase in the price benefits Home firms, and producer surplus rises by the amount (a + b + c). We also need to take into account the cost of the subsidy. Because the amount of the subsidy is s, and the amount of Home exports (after the subsidy) is X2 = S2 − D2, it follows that the revenue cost of the subsidy to the government is the area (b + c + d + e), which equals s · X2 (the government pays s for every unit exported). Therefore, the overall impact of the subsidy in the large country can be summarized as follows:

336

In the world market, panel (b), the triangle (b + d) is the deadweight loss due to the subsidy, just as it is for a small country. For the large country, however, there is an extra source of loss, the area e, which is the terms-of-trade loss to Home: e = e′ + f in panel (b). When we analyze Foreign and world welfare, it will be useful to divide the Home terms-of-trade loss into two sections, e′ and f, but from Home’s perspective, the terms-of-trade welfare loss is just their sum, area e. This loss is the decrease in export revenue because the world price has fallen to P*; Home loses the difference between PW and P* on each of X2 units exported. So a large country loses even more from a subsidy than a small country because of the reduction in the world price of its exported good.

Home loses, but Foreign gains because of the TOT effect. So why not use export subsidies as a reason to redistribute income from rich to poor countries?

Foreign and World Welfare While Home definitely loses from the subsidy, the Foreign importing country definitely gains. Panel (b) of Figure 10-2 illustrates the consumer surplus benefit to Foreign of the Home subsidy; the price of Foreign imports decreases and Foreign’s terms of trade improves. The change in consumer surplus for Foreign is area e′, the area below its import demand curve M* and between the free-trade world price PW and the new world price (with subsidy) P*.

When we combine the total Home consumption and production losses (b + d) plus the Home terms-of-trade loss e, and subtract the Foreign terms-of-trade gain e′, there is an overall deadweight loss for the world, which is measured by the area (b + d + f) in panel (b). The area f is the additional world deadweight loss due to the subsidy, which arises because the terms-of-trade loss in Home is not completely offset by a terms-of-trade gain in Foreign.

Answer: Because it would be more efficient just to give cash transfers. This is where the U.S. and EU have parted ways.

Because there is a transfer of terms of trade from Home to Foreign, the export subsidy might seem like a good policy tool for large wealthy countries seeking to give aid to poorer countries. However, this turns out not to be the case. The deadweight loss f means that using the export subsidy to increase Home production and send the excess exported goods overseas (as was the case for food aid, discussed earlier as an example of an indirect subsidy) is an inefficient way to transfer gains from trade among countries. It would be more efficient to simply give cash aid in the amount of the Home terms-of-trade loss to poor importers, a policy approach that, because it does not change the free-trade levels of production and consumption in either country, would avoid the deadweight loss (b + d + f) associated with the subsidy. This argument is made by the European countries, which, several years ago, eliminated transfers of food as a form of aid and switched to cash payments. The United States has now agreed to make the same policy change, as discussed in the following application.

Use these tools to look at who would gain and who would lose from the abolition of export subsidies debated at the WTO. Gainers: Agricultural exporting developing countries would benefit from higher prices; developed countries would benefit from the elimination of the deadweight and TOT losses. Losers: Agricultural importers, particularly the poorest countries.Food Aid reduces local agricultural prices and hurt local farmers. Europe argues it would be better to buy food from local farmers and then distribute it to the poor. However, the U.S. still provides a lot of food aid, and it is unlikely that the WTO will agree to abolish it.

Students will ask why the U.S. and EU have these policies, if they cause an overall loss in welfare. The answer is that farmers lobby.

Although it is true that very poor agricultural importers would be hurt by the increase in prices if these subsidies were abolished.

Who Gains and Who Loses?

Now that we have studied the effect of export subsidies on world prices and trade volume in theory, we return to the agreements of the Hong Kong meeting of the WTO in December 2005 and ask: Which countries will gain and which will lose when export subsidies (including the “indirect” subsidies like food aid) are ever eliminated?

Gains The obvious gainers from this action will be current agricultural exporters in developing countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, and Thailand, along with potential exporters such as India and China. These countries will gain from the rise in world prices as agricultural subsidies by the industrialized countries—especially Europe and the United States—are eliminated. These countries will gain even more when and if an agreement is reached on the elimination of agricultural tariffs in the industrial countries, including Japan and South Korea, that protect crops such as rice. Both of these actions will also benefit the industrial countries themselves, which suffer both a deadweight loss and a terms-of-trade loss from the combination of export subsidies and import tariffs in agriculture. Farmers in the industrial countries who lose the subsidies will be worse off, and the government might choose to offset that loss with some type of adjustment assistance. In the United States and Europe, however, it is often the largest farmers who benefit the most from subsidy programs, and they may be better able to adjust to the elimination of subsidies (through switching to other crops) than small farmers.

337

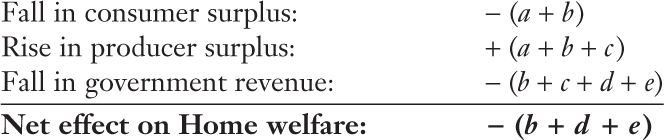

Losses Which countries will lose from the elimination of export subsidies? To the extent that the elimination of export subsidies leads to higher world prices, as we expect from our analysis (in Figure 10-2, the price would rise from P* to PW), then the food-importing countries, typically the poorer non-food-producing countries, will lose. This theoretical result is confirmed by several empirical studies. One study found that the existing pattern of agricultural supports (tariffs and subsidies) raises the per capita income of two-thirds of 77 developing nations, including most of the poorest countries, such as Burundi and Zambia.3 This result is illustrated in Figure 10-3. Panel (a) shows net agricultural exports graphed against countries’ income per capita over the period 1990 to 2000. The poorer countries (i.e., those lower on the income scale on the horizontal axis) export more agricultural products and therefore would benefit from a rise in their prices. But for food exports in panel (b), rather than total agricultural exports (which includes non-food items like cotton), it is the middle-income countries that export the most. Panel (c) shows that poor countries are net importers of essential food items such as corn, rice, and wheat (summarized as “cereal exports”) and would be harmed by an increase in their world price. Many of the world’s poorest individuals depend on cereal crops for much of their diet and would be especially hard hit by any increase in those prices.

Food Aid What about indirect subsidies such as food aid? The United States has been a principal supplier of food aid, which it uses for both humanitarian purposes and to get rid of surpluses of food products at home. No country will argue with the need for donations in cases of starvation, as have occurred recently in the Darfur region of Sudan and in 1984 in Ethiopia, but the United States also provides food shipments to regions without shortages, an action that can depress local prices and harm local producers. European countries stopped this practice many years ago and argue that it is better to instead have United Nations relief agencies buy food from local farmers in poor regions and then distribute it to the poorest individuals in a country. In this way, the European countries boost production in the country and help to feed its poorest citizens. In the Hong Kong talks, the European Union insisted that the indirect subsidies to regions without shortages be eliminated.

338

Even though the proposals from the Hong Kong talks were never ratified and the elimination of tariff and subsidies in agriculture has not occurred, the Doha Round of negotiations is still ongoing and some progress has been made toward the goal of replacing food aid with efforts to increase production. In 2009, the Group of Eight (G8)4 countries pledged to increase funding for agricultural development by $12 billion per year, as described in Headlines: G8 Shifts Focus from Food Aid to Farming. This pledge represents a shift in focus away from food aid and toward agricultural sustainability in developing countries. As the Headlines article describes, this approach is a major shift in focus for the United States, where 20 times more money has been spent on food aid than on projects to increase local production.

There is a better way of helping them.

339

Despite this announcement, however, many observers remain skeptical that the funding for agricultural development in poor countries will be forthcoming. After the G8 summit many editorials appeared challenging these countries to follow through on their pledges. We include one of these editorials in Headlines: Hunger and Food Security Back on Political Agenda; this one written by the chairman of the European Food Security Group, a network of 40 European nongovernmental organizations.

The G8 announces policies to encourage agriculture in developing countries, rather than providing food aid.

G8 Shifts Focus from Food Aid to Farming

This article announces a new “food security initiative” from the G8 countries, who promised billions of dollars to assist farmers in developing countries. As the next Headlines article describes, however, not all observers believe that these funds will be forthcoming, despite the overwhelming need for the assistance.

The G8 countries will this week announce a “food security initiative,” committing more than $12 [billion] for agricultural development over the next three years, in a move that signals a further shift from food aid to long-term investments in farming in the developing world.

The US and Japan will provide the bulk of the funding, with $3–$4 [billion] each, with the rest coming from Europe and Canada, according to United Nations officials and Group of Eight diplomats briefed on the “L’Aquila Food Security Initiative.” Officials said it would more than triple spending….

The G8 initiative underscores Washington’s new approach to fighting global hunger, reversing a two-decades-old policy focused almost exclusively on food aid. Hillary Clinton, US secretary of state, and Tom Vilsack, the agriculture secretary, have both highlighted the shifting emphasis in recent speeches.

“For too long, our primary response [to fight hunger] has been to send emergency [food] aid when the crisis is at its worst,” Ms. Clinton said last month. “This saves lives, but it doesn’t address hunger’s root causes. It is, at best, a short-term fix.”

Washington’s shift could prove contentious in the US, as its farmers are the largest exporters of several crops, including soyabean and corn. The US is the world’s largest donor of food aid—mainly crops grown by US farmers, costing more than $2 [billion] last year.

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, a think-tank, estimates that Washington spends 20 times more on food aid than on long-term schemes in Africa to boost local food production. US annual spending on African farming projects topped $400 [million]in the 1980s, but by 2006 had dwindled to $60 [million], the council said in a report this year….

Source: Excerpted from Javier Blas, “G8 Shifts Focus from Food Aid to Farming,” Financial Times, July 6, 2009, p. 1. From the Financial Times © The Financial Times Limited 2009. All Rights Reserved.

340

An article skeptical of whether the G8 will implement these policies.

Hunger and Food Security Back on Political Agenda

This article expresses skepticism that the promises of the G8 countries for billions of dollars to assist farmers in developing countries will be forthcoming.

Global food security is a political and economic priority for the first time since the early 1970s. That should be the key message from the decision by the G8 group of leading economic nations to endorse a “food security initiative” at their meeting in Italy this week. But this welcome decision needs to be followed up by further significant policy change at national and international level if food security is to be achieved for the world’s growing population over the coming decades….

It is reported that the initiative will involve a commitment of $12 billion for agricultural development over the next three years. But before giving three cheers for the G8, two critical questions must be answered. Is the $12 billion additional resources or a repackaging of existing commitments? How can this initiative feed into sustained policy change aimed at increasing food security at household, national and global level?

Policy change is necessary in many countries which are currently food insecure. Investment in agricultural and rural development has been shamefully neglected over the past 30 years. Donors, including the World Bank, also bear responsibility for this. There must now be an acceptance that budget allocations to agriculture must increase and must be sustained…. The history of such summits is not good: the gap between the promises and subsequent actions is great. At the first such summit in 1974, Dr. Henry Kissinger made the pledge that “within 10 years, no child will go to bed hungry.”

The G8 food security initiative at least provides a positive backdrop to the summit. It should provide an opportunity to many developing countries to commit to the type of policy change necessary to increase their own food security. With one billion hungry people in the world, with growing populations and with the threat that climate change presents to agricultural production capacity, such a commitment is both critical and urgent. It is good politics and good economics to do so.

Source: Excerpted from Tom Arnold, “Hunger and Food Security Back on Political Agenda,” The Irish Times, July 8, 2009, electronic edition.