4 Production Subsidies

WTO distinguishes between export subsidies to agriculture and other production subsidies. This is because production subsidies should have a smaller effect on exports than export subsidies: A production subsidy provides a per unit subsidy for all units produced, rather than just for exports.

1. Effect of a Production Subsidy in a Small Home CountryThe production subsidy raises the price received by producers, so that quantity supplied increases. However, Home consumers continue to pay the world price, so quantity demanded does not change. Therefore exports increase by less than for an export subsidy.

a. Home Welfare

Unlike a tariff there is no consumption loss, only a production loss.

b. Targeting Principle

To stimulate production, it is better to subsidize production than exports. This is an example of the targeting principle, that to achieve an objective it is best to use an instrument that achieves it most directly.

2. Effect of the Production Subsidy in a Large Home CountrySince there is a smaller increase in exports with the production subsidy than with the export subsidy, there is a smaller deterioration of the terms of trade.

a. Summary: Production subsidies in agriculture lower world prices by less than export subsidies, and cause smaller deadweight losses. So the WTO is less worried about production subsidies.

The agreements reached in Hong Kong in 2005 distinguish between export subsidies in agriculture—which will be eliminated—and all other forms of domestic support that increase production (e.g., tax incentives and other types of subsidies). The agreements make this distinction because other forms of agricultural support are expected to have less impact on exports than direct subsidies. Therefore, there is less impact on other countries from having domestic support programs as compared with export subsidies. To illustrate this idea, let’s examine the impact of a “production subsidy” in agriculture for both a small and a large country.

Suppose the government provides a subsidy of s dollars for every unit (e.g., ton of sugar in our example) that a Home firm produces. This is a production subsidy because it is a subsidy to every unit produced and not just to units that are exported. There are several ways that a government can implement such a subsidy. The government might guarantee a minimum price to the farmer, for example, and make up the difference between the minimum price and any lower price for which the farmer sells. Alternatively, the government might provide subsidies to users of the crop to purchase it, thus increasing demand and raising market prices; this would act like a subsidy to every unit produced. As mentioned earlier, the United States has used both methods to support its cotton growers.

341

These policies all fall under Article XVI of the GATT (see Side Bar: Key Provisions of the GATT in Chapter 8). Article XVI states that partner countries should be notified of the extent of such subsidies, and when possible, they should be limited. In Hong Kong, the WTO members further agreed to classify countries according to the extent of such subsidies, with the European Union classified as having a high level of production subsidies, the United States and Japan having a middle level, and all other countries having low subsidies (see Table 10-1). Future discussion will determine the timing and extent of cuts in these production subsidies.

Effect of a Production Subsidy in a Small Home Country

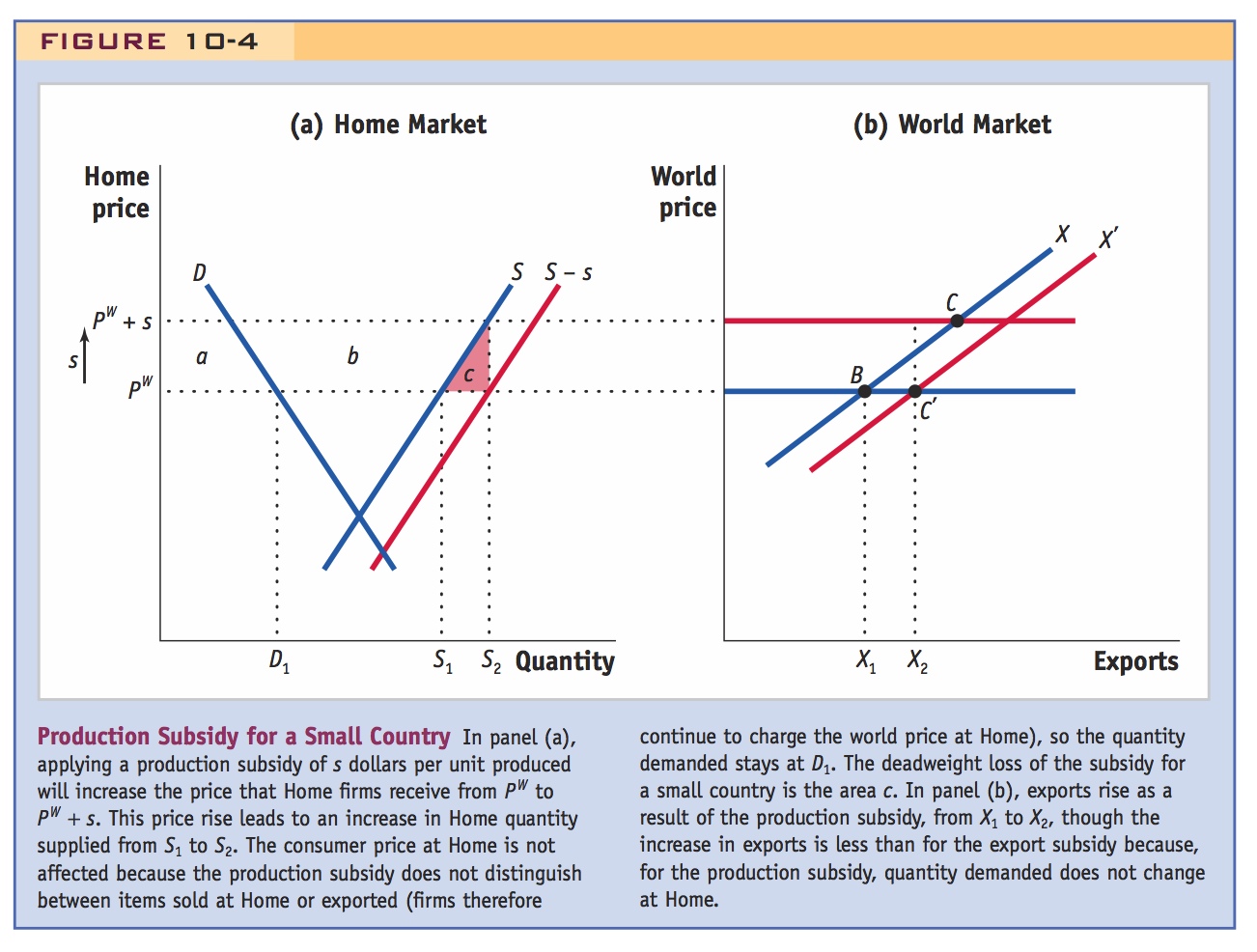

To illustrate the effect of a production subsidy, we begin with a small country that faces a fixed world price of PW. In Figure 10-4, panel (a), the production subsidy of s increases the price received by Home producers to PW + s and increases Home’s quantity supplied from S1 to S2. The quantity demanded at Home does not change, however, because producers continue to charge the world price at Home. This is the case (in contrast to the export subsidy) because Home producers receive a subsidy regardless of whom they sell to (domestic consumers or Foreign consumers through exporting). So with a production subsidy, Home producers charge the world price to Foreign consumers and receive the extra subsidy from the government and likewise charge the world price to Home consumers, and again receive the extra subsidy. In contrast, for an export subsidy, Home firms receive the subsidy only for export sales and not for domestic sales.

342

Because the price for Home consumers with the production subsidy is still PW, there is no change in the quantity demanded at Home, which remains at D1. In panel (b), we see that the production subsidy increases the quantity of exports from X1 = S1 − D1 to X2 = S2 − D1. Because demand is not affected, the production subsidy increases exports by less than an export subsidy would. That result occurs because the quantity demanded decreases with an export subsidy due to higher Home prices, leading to greater Home exports. In contrast, with the production subsidy, the quantity demanded at Home is unchanged, so exports do not rise as much.

Conclusion: Since demand is unaffected there is only a production deadweight loss.

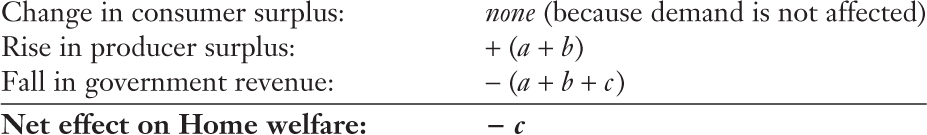

Home Welfare With the increase in the price received by Home producers, from PW to PW + s, there is a corresponding rise in producer surplus of the amount (a + b) in panel (a). The government revenue cost of the subsidy is the entire area (a + b + c), which equals the amount of the subsidy s, times Home production S2. So the overall impact of the production subsidy is

The deadweight loss caused by the production subsidy in a small country, area c, is less than that caused by the export subsidy in Figure 10-1, which is area (b + d). The reason that the production subsidy has a lower deadweight loss than the export subsidy is that consumer decisions have not been affected at all: Home consumers still face the price of PW. The production subsidy increases the quantity supplied by Home producers, just as an export subsidy does, but the production subsidy does so without raising the price for Home consumers. The only deadweight loss is in production inefficiency: the higher subsidized price encourages Home producers to increase the amount of production at higher marginal costs (i.e., farther right along the supply curve) than would occur in a market equilibrium without the subsidy.

Targeting Principle Our finding that the deadweight loss is lower for the production subsidy makes it a better policy instrument than the export subsidy to achieve an increase in Home supply. This finding is an example of the targeting principle: to achieve some objective, it is best to use the policy instrument that achieves the objective most directly. If the objective of the Home government is to increase cotton supply, for example, and therefore benefit cotton growers, it is better to use a production subsidy than an export subsidy. Of course, the benefits to cotton growers come at the expense of government revenue.

Depending upon the students' background, you might also point out applications of the targeting principle in macroeconomics. Example: Y2K at the millenium raises money demand. To get back to full employment it would be better to use an expansionary monetary policy than an expansionary fiscal policy.

There are many examples of this targeting principle in economics. To limit the consumption of cigarettes and improve public health, the best policy is a tax on cigarette purchases, as many countries use. To reduce pollution from automobiles, the best policy would be a tax on gasoline, the magnitude of which is much higher in Europe than in the United States. And, to use an example from this book, to compensate people for losses from international trade, it is better to provide trade adjustment assistance directly (discussed in Chapter 3) to those affected than to impose an import tariff or quota.

343

Effect of the Production Subsidy in a Large Home Country

We will not draw the large-country case in detail but will use Figure 10-4 to briefly explain the effects of a production subsidy on prices, exports, and welfare. When the price for Home producers rises from PW to PW + s, the quantity of the exported good supplied increases from S1 to S2. Because demand has not changed, exports increase by exactly the same amount as the quantity supplied by domestic producers. We show that increase in exports by the outward shift of the export supply curve, from X to X′ in panel (b). As mentioned previously, the rise in the quantity of exports due to the production subsidy, from point B to C′ in Figure 10-4, is less than the increase in the quantity of exports for the export subsidy, from point B to C′ shown in Figure 10-1. With the export subsidy, the price for Home producers and consumers rose to PW + s, so exports increased because of both the rise in quantity supplied and the drop in quantity demanded. As a result, the export subsidy shifted down the Home export supply curve by exactly the amount s in Figure 10-1. In contrast, with a production subsidy, exports rise only because Home quantity supplied increases so that export supply shifts down by an amount less than s in Figure 10-4.

If we drew a downward-sloping Foreign import demand curve in panel (b), then the increase in supply as a result of the production subsidy would lower the world price. But that drop in world price would be less than the drop that occurred with the export subsidy because the increase in exports under the production subsidy is less.

There is a smaller increase in exports, so world prices decrease less.

Summary Production subsidies in agriculture still lower world prices, but they lower prices by less than export subsidies. For this reason, the WTO is less concerned with eliminating production subsidies and other forms of domestic support for agriculture. These policies have a smaller impact on world prices and, as we have also shown, a smaller deadweight loss as compared with that of export subsidies.