5 Export Tariffs

Export tariffs so obviously hurt both consumers and producers that students wonder why they would used at all. The answer, of course, is that it is a reliable source of government revenue in countries that lack a sound fiscal system.

Export tariffs provide a source of revenue to the government, but do not benefit producers. Examples: Argentine agricultural products, Mozambican diamonds, Thai teak wood.

1. Impact of an Export Tariff in a Small Country

The tariff reduces the domestic price, raising quantity demand lowering quantity supplied. Exports fall. The export supply curve shifts up.

a. Impact of the Export Tariff on Small Country Welfare

Consumer surplus increases, producer surplus falls, and the government gains revenue. Consumption and production losses produce a deadweight loss.

2. Impact of an Export Tariff in a Large Country

Since exports fall, there is an improvement in the TOT. However, the increase in the world price is less than the tariff, so part of the burden of the tariff is shifted to Foreign consumers. There is a deadweight loss, but it is offset by a TOT gain equal to the increase in the value of exports caused by the increase in price. If the TOT gain exceeds the deadweight loss, Home may be better off. However, this is a beggar-thy-neighbor policy; it makes the Foreign country worse off by making it pay more for its imports.

Export and production subsidies are not the only policies that countries use to influence trade in certain products. Some countries apply export tariffs—which are taxes applied by the exporting country when a good leaves the country. As we saw in the introduction to this chapter, Argentina applies export tariffs on many of its agricultural products. Mozambique charges a tariff on exports of diamonds, and Thailand charges a tariff on exports of teak wood. The main purpose of these export tariffs is to raise revenue for the government; farmers and other companies do not benefit from the export tariffs, because they pay the tax.

For what it is worth, note that export tariffs are unconstitutional in the U.S.

In this section we look at how export tariffs affect the overall welfare of the exporting country, taking into account the effects on consumers, producers, and government revenue. We start with the case of a small exporting country, facing fixed world prices. Following that, we look at how the outcome differs when the country is large enough to affect world prices.

344

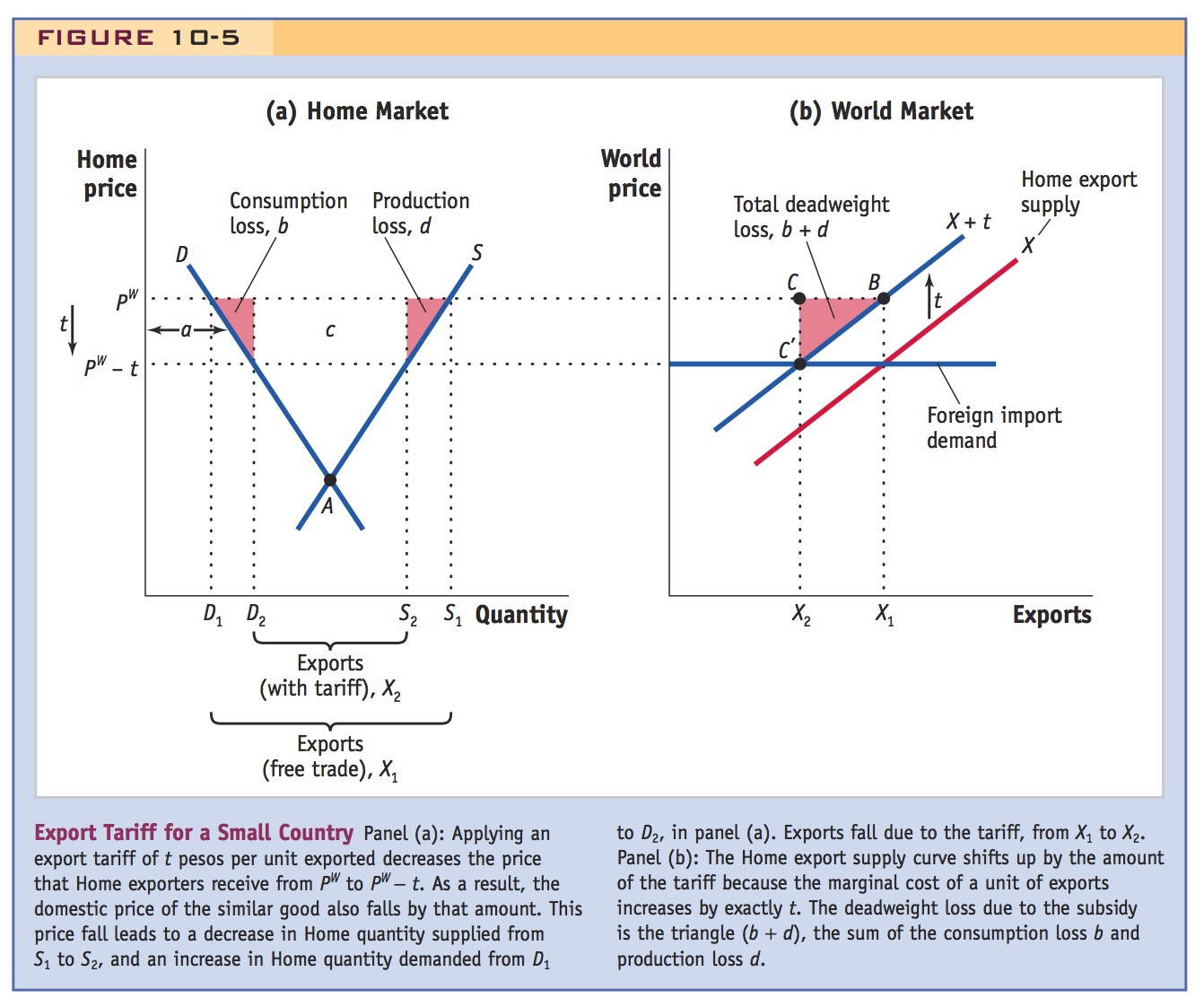

Impact of an Export Tariff in a Small Country

Consider a small country (like Argentina) that exports soybeans. The Home no-trade equilibrium is shown at point A in panel (a) of Figure 10-5. With free trade, Home faces a world price of soybeans of PW pesos (we are using the currency of Argentina). At that price, the quantity supplied at Home is S1 and the quantity demanded is D1 in panel (a), so Home will export soybeans. The quantity of exports is X1 = S1 − D1, which is shown by point B in panel (b). So far, the free trade equilibrium in Figure 10-5 is the same as that in Figure 10-1, which showed the impact of an export subsidy. But the two figures will change when we consider the effects of an export tariff.

Now suppose that the government applies a tariff of t pesos to the exports of soybeans. Instead of receiving the world price of PW, producers will instead receive the price of PW − t for their exports, because the government collects t pesos. If the price they receive at Home is any higher than this amount, then producers will sell only in the Home market and not export at all. As a result there would be an oversupply at Home and the local price would fall. Thus, in equilibrium, the Home price must also fall to equal the export price of PW − t.

345

With the price falling to PW − t, the quantity supplied in Home falls to S2, and the quantity demanded increases to D2 in panel (a). Therefore, Home exports fall to X2 = S2 − D2. The change in the quantity of exports can be thought of as a leftward, or upward, shift of the export supply curve in panel (b), where we measure the world price rather than the Home price on the vertical axis. The export supply curve shifts up by the amount of the tariff t. This result is analogous to what happened when we introduced a subsidy in Figure 10-1. In that case, the export supply curve fell by the amount of the subsidy s.

The new intersection of supply and demand in the world market is at point C in panel (b), with exports of X2. Alternatively, on the original export supply curve X, exports of X2 occur at the point C′ and the domestic price of PW − t.

Only the government benefits.

Impact of the Export Tariff on Small Country Welfare We can now determine the impact of the tariff on the welfare of the small exporting country. Since the Home price falls because of the export tariff, consumers benefit. The rise in consumer surplus is shown by area a in panel (a). Producers are worse off, however, and the fall in producer surplus is shown by the amount (a + b + c + d). The government collects revenue from the export tariff, and the amount of revenue equals the amount of the tariff t times exports of X2, area c.

Adding up the impact on consumers, producers, and government revenue, the overall impact of the export tariff on the welfare of a small exporting country is:

Students should be getting the hang of this by now, so you can go through this quickly.

To sum up, the export tariff for a small country has a deadweight loss of (b + d). (This outcome is similar to the results of the import tariff that we studied in Chapter 8 and the export subsidy we studied earlier in this chapter.) That loss can be broken up into two components. The triangle b in panel (a) is the consumption loss for the economy. It occurs because as consumers increase their quantity from D1 to D2, the amount that they value these extra units varies between PW and PW − t, along their demand curve. The true cost to the economy of these extra units consumed is always PW. Therefore, the value of the extra units is less than their cost to the economy, indicating that there is a deadweight loss.

Triangle d is the production loss for the economy. It occurs because as producers reduce their quantity from S1 to S2, the marginal cost of supplying those units varies between PW and PW − t, along their supply curve. But the true value to the economy of these extra units consumed is always PW, because that is the price at which they could be exported without the tariff. Therefore, the value of the forgone units exceeds their cost to the economy, indicating again that there is a deadweight loss.

Impact of an Export Tariff in a Large Country

State the intuition first: Since exports will be lower, the world price will increase and Home will enjoy a TOT gain.

We have shown that the export tariff in a small country leads to a decline in overall welfare. Despite that, some governments—especially in developing countries—find that export tariffs are a convenient way to raise revenue, because it is very easy to apply the tax at border stations as goods leave the country. The fact that the economy overall suffers a loss does not prevent governments from using this policy.

346

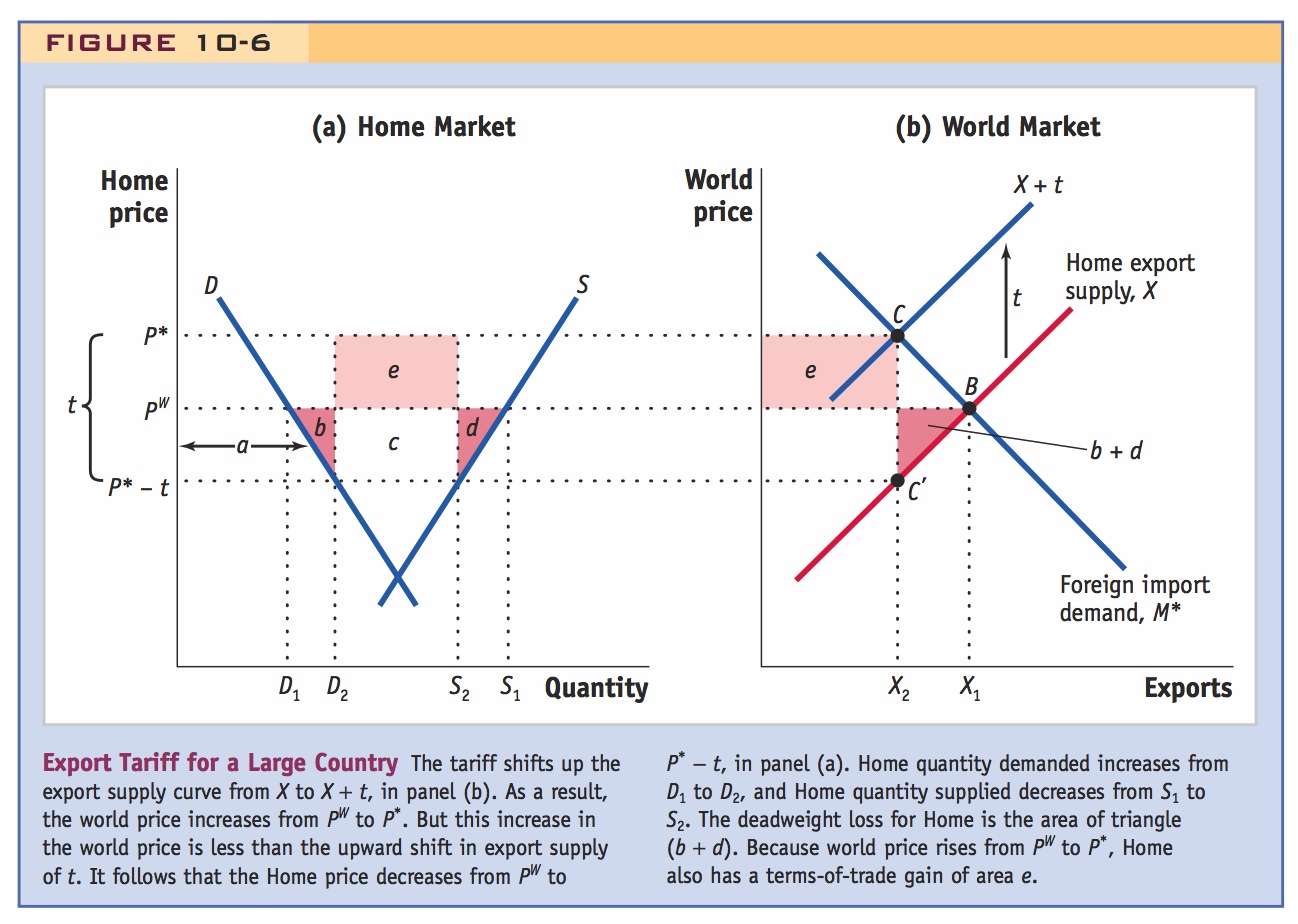

What happens in a large exporting country? Does an export tariff still produce an overall loss? Recall from Chapter 8 that an import tariff in a large country would lead to an overall gain rather than a loss, provided that the tariff is not too high. This gain arises because the import tariff reduces demand for the imported product, and therefore lowers its price, which leads to a terms-of-trade gain. In this section, we see that an export tariff also leads to a terms-of-trade gain. That result occurs because an export tariff reduces the amount supplied to the world market, and therefore increases the price of the export product, which is a terms-of-trade gain.

Figure 10-6 illustrates the effect of an export tariff for a large country. Under free trade the price of soybeans is PW, which is at the intersection of Home export supply X and Foreign import demand M* in panel (b). When the government applies a tariff of t pesos to soybean exports, the Home export supply curve shifts up by exactly the amount of the tariff from X to X + t. The new intersection of the Home export supply curve and the Foreign import demand curve occurs at point C, and the world price has risen from PW to P*.

The price P* is paid by Foreign buyers of soybeans and includes the export tariff. The Foreign import demand curve M* is downward sloping rather than horizontal as it was in Figure 10-5 for a small country. Because the Foreign import demand curve slopes downward, the price P* is greater than PW but not by as much as the tariff t, which equals the upward shift in the export supply curve. Home receives price P* − t, which is measured net of the export tariff. Because P* has risen above PW by less than the amount t, it follows that P* − t falls below PW, as shown in panel (a).

347

Impact of the Export Tariff on Large Country Welfare We can now determine the impact of the tariff on the welfare of the large exporting country. Home consumer and producers faced the free trade price of PW under free trade, but face the lower price of P* − t once the tariff is applied. The rise in consumer surplus is shown by area a in panel (a) and the fall in producer surplus is shown by area (a + b + c + d). The revenue the government collects from the export tariff equals the amount of the tariff t times exports of X2, by area (c + e).

Adding up the impacts on consumers, producers, and government revenue, the overall impact of the export tariff on the welfare of a large exporting country is:

Compared with the effect of an export tariff for a small country, we find that the net effect on large-country Home welfare can be positive rather than negative, as long as e < (b + d). The amount (b + d) is still the deadweight loss; area e is the terms-of-trade gain due to the export tariff. In either panel of Figure 10-6, this terms-of-trade gain is measured by the rise in the price paid by Foreign purchasers of soybeans, from PW to P*, multiplied by the amount of exports X2. This terms-of-trade gain is the “extra” money that Home receives from exporting soybeans at a higher price. If the terms-of-trade gain exceeds the deadweight loss, then the Home country gains overall from applying the tariff.

To sum up, the effect of an export tariff is most similar to that of an import tariff because it leads to a terms-of-trade gain. In Chapter 8 we argued that for an import tariff that is not too high, the terms-of-trade gain e would always exceed the deadweight loss (b + d). That argument applies here, too, so that for export tariffs that are not too high, the terms-of-trade gain e exceeds the deadweight loss and Home country gains. In Chapter 8 we stressed that this terms-of-trade gain came at the expense of the Foreign country, which earns a lower price for the product it sells under an import tariff. Similarly, the Foreign country loses under an export tariff because it is paying a higher price for the product it is buying. So, just as we called an import tariff a beggar-thy-neighbor policy, the same idea applies to export tariffs because they harm the Foreign country. These results are the opposite of those we found for an export subsidy, which for a large Home country always leads to a terms-of-trade loss for Home and a benefit for Foreign buyers.