2 Globalization of Finance: Debts and Deficits

There has been rapid globalization

of finance in recent years. To understand, review basic concepts of income, expenditure, and wealth, applied at the national level. Discuss the effects of default.

1. Deficits and Surpluses: The Balance of Payments

Running deficit requires you to borrow; running a surplus means you are lending. Look at data on the U.S. current account (CA). The U.S. is borrowing from other countries.

a. Key Topics: How do different types of transactions affect the CA? How are CA imbalances financed? How long can they be sustained? Why do some countries have CA deficits, and others surpluses? What is the function of CA imbalances in a well-functioning economy? Why are they so hotly debated?

2. Debtors and Creditors: External Wealth

Define a country’s external wealth as its net worth—the difference between its foreign assets and liabilities. CA surpluses can increase external wealth, while deficits can reduce it. However, it is also affected by capital gains or losses, as well as changes in the value of a country’s liabilities, which can change if debtors default.

a. Key Topics: What forms can external wealth take? Does its composition matter? What explains the level of external wealth and its change over time? How important is the CA in determining wealth? How does this affect a country’s current and future welfare?

3. Darlings and Deadbeats: Defaults and Other Risks

Recent historical examples of sovereign defaults. Note that sovereign states can default without legal penalty. Investors deal with sovereign default risk by monitoring debtors; credit ratings.

a. Key Topics: What causes sovereign defaults? What are there consequences? What determines risk premiums? How do risk premia affect the macroeconomy?

4. Summary and Plan of Study

Coming chapters expand upon these insights: Chapter 16, the balance of payments; Chapter 17, the role of CA imbalances in a well-functioning economy; Chapter 18, the role of imbalances in the macroeconomy in the short run, and the effects of monetary and fiscal policies; Chapter 19, the effects of exchange rate fluctuations on wealth and its macroeconomic consequences; Chapter 20, risk premia for exchange rates and the link between default and currency crises; Chapter 22, more detailed treatment of topics such as global imbalances and default.

Financial development is a defining characteristic of modern economies. Households’ use of financial instruments such as credit cards, savings accounts, and mortgages is taken for granted, as is the ability of firms and governments to use the products and services offered in financial markets. A few years ago, very little of this financial activity spilled across international borders; countries were very nearly closed from a financial standpoint. Today many countries are more open: financial globalization has taken hold around the world, starting in the economically advanced countries and spreading to many emerging market countries.

Although you might expect that you need many complex and difficult theories to understand the financial transactions between countries, such analysis requires only the application of familiar household accounting concepts such as income, expenditure, and wealth. We develop these concepts at the national level to understand how flows of goods, services, income, and capital make the global macroeconomy work. We can then see how the smooth functioning of international finance can make countries better off by allowing them to lend and borrow. Along the way, we also find that financial interactions are not always so smooth. Defaults and other disruptions in financial markets can mean that the potential gains from globalization are not so easily realized in practice.

Deficits and Surpluses: The Balance of Payments

Do you keep track of your finances? If so, you probably follow two important figures: your income and your expenditure. The difference between the two is an important number: if it is positive, you have a surplus; if it is negative, you have a deficit. The number tells you if you are living within or beyond your means. What would you do with a surplus? The extra money could be added to savings or used to pay down debt. How would you handle a deficit? You could run down your savings or borrow and go into deeper debt. Thus, imbalances between income and expenditure require you to engage in financial transactions with the world outside your household.

9

The students may be familiar with the trade balance, but not with the CA yet. For the moment just say that the CA is a generalization of the TB. Emphasize-- using the household analogy--that a CA deficit implies that we are borrowing, and a surplus means lending.

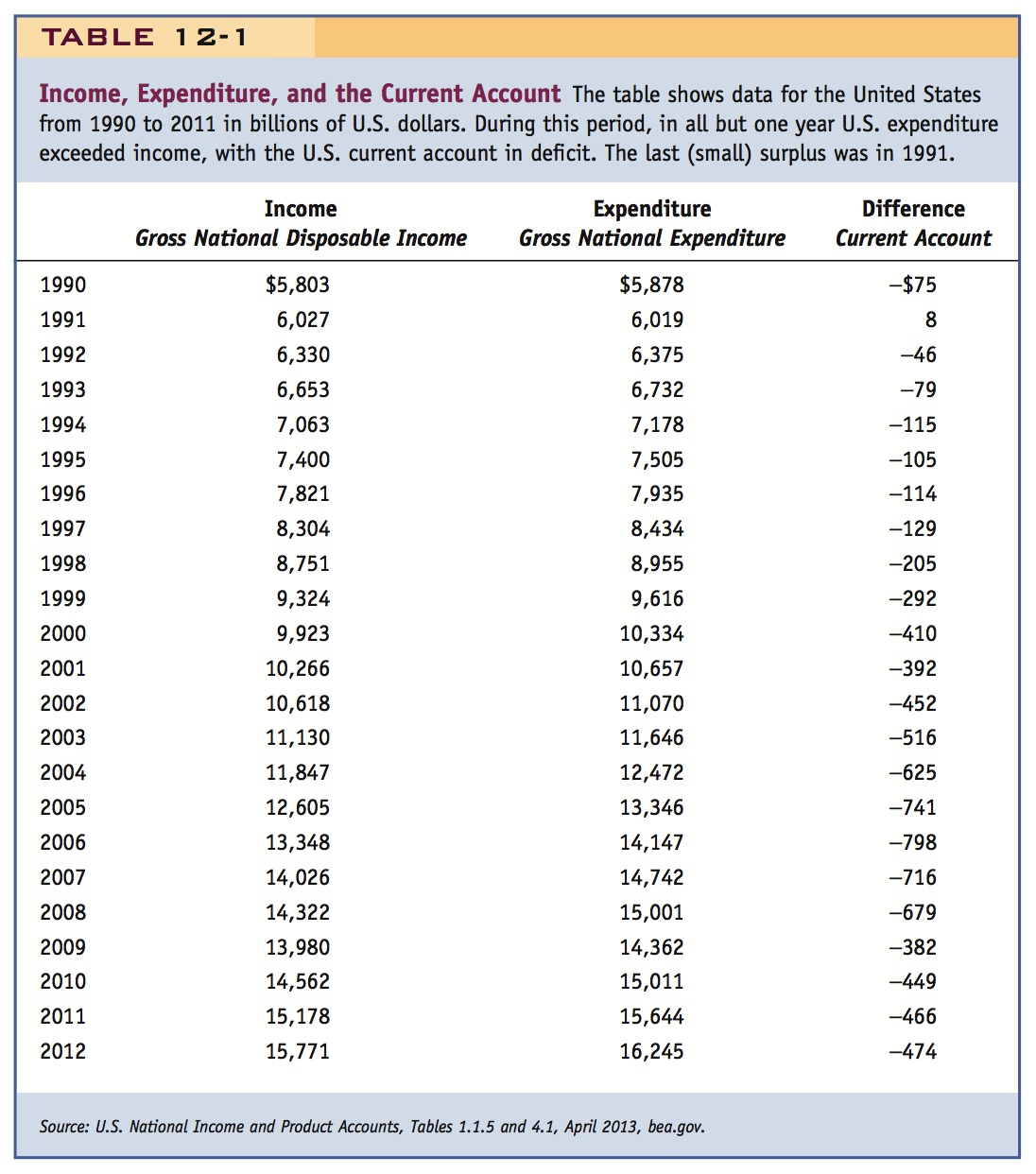

At the national level, we can make the same kinds of economic measurements of income, expenditure, deficit, and surplus, and these important indicators of economic performance are the subject of heated policy debate. For example, Table 12-1 shows measures of U.S. national income and expenditure since 1991 in billions of U.S. dollars. At the national level, the income measure is called gross national disposable income; the expenditure measure is called gross national expenditure. The difference between the two is a key macroeconomic aggregate called the current account.

Again, go online and show students the most recent data too.

Since posting a small surplus in 1991, the U.S. deficit on the current account (a negative number) has grown much larger and at times it has approached $1 trillion per year, although it fell markedly in the latest recession. That is, U.S. income has not been high enough to cover U.S. expenditure in these years. How did the United States bridge this deficit? It engaged in financial transactions with the outside world and borrowed the difference, just as households do.

10

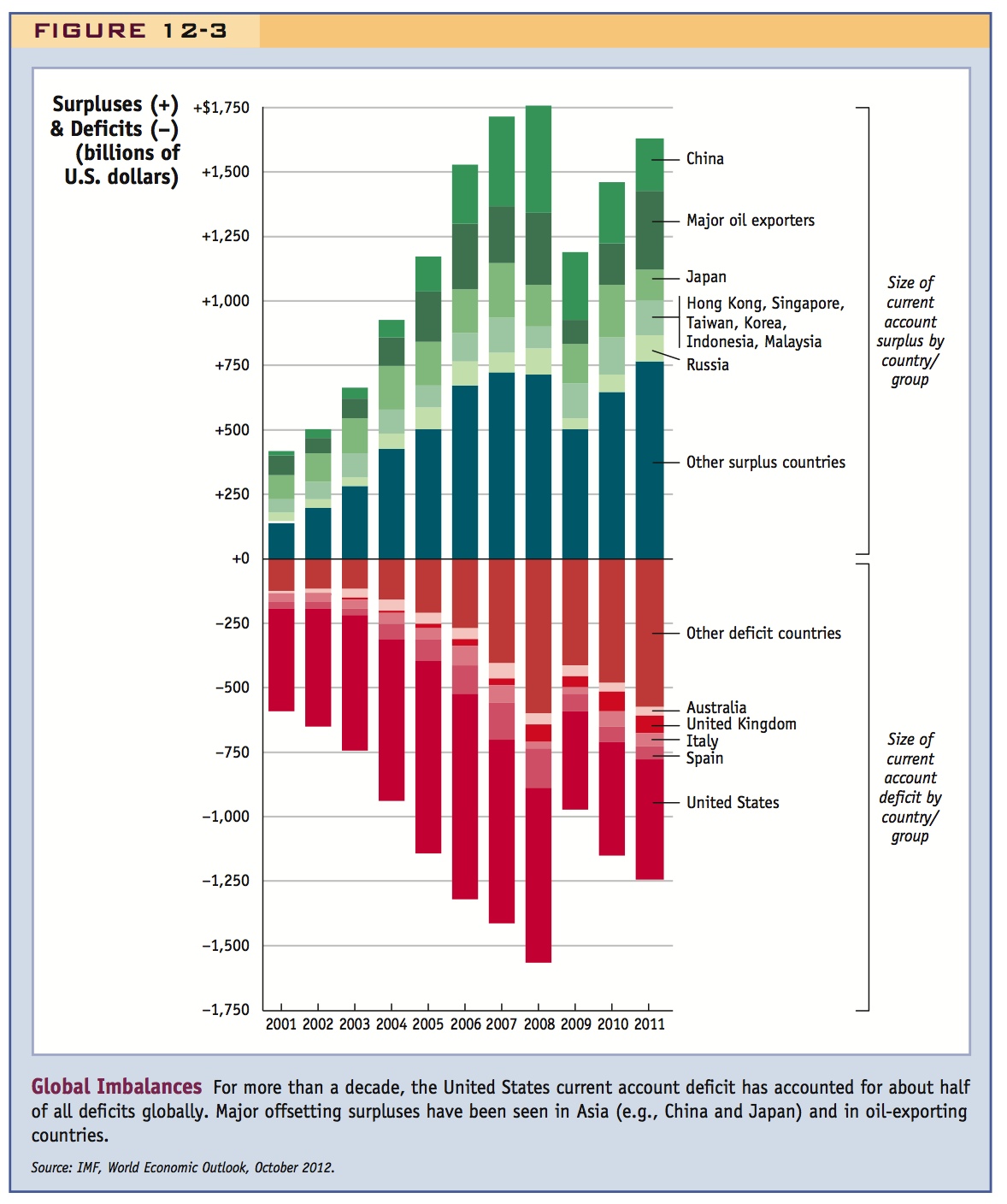

Because the world as a whole is a closed economy (we can’t borrow from outer space, as yet), it is impossible for the world to run a deficit. If the United States is a net borrower, running a current account deficit with income less than expenditure, then the rest of the world must be a net lender to the United States, running surpluses with expenditure less than income. Globally, the world’s finances must balance in this way, even if individual countries and regions have surpluses or deficits. Figure 12-3 shows the massive scale of some of these recent imbalances, dramatically illustrating the impact of financial globalization.

11

Key Topics How do different international economic transactions contribute to current account imbalances? How are these imbalances financed? How long can they persist? Why are some countries in surplus and others in deficit? What role do current account imbalances perform in a well-functioning economy? Why are these imbalances the focus of so much policy debate?

Debtors and Creditors: External Wealth

To understand the role of wealth in international financial transactions, we revisit our household analogy. Your total wealth or net worth is equal to your assets (what others owe you) minus your liabilities (what you owe others). When you run a surplus, and save money (buying assets or paying down debt), your total wealth, or net worth, tends to rise. Similarly, when you have a deficit and borrow (taking on debt or running down savings), your wealth tends to fall. We can use this analysis to understand the behavior of nations. From an international perspective, a country’s net worth is called its external wealth and it equals the difference between its foreign assets (what it is owed by the rest of the world) and its foreign liabilities (what it owes to the rest of the world). Positive external wealth makes a country a creditor nation (other nations owe it money); negative external wealth makes it a debtor nation (it owes other nations money).

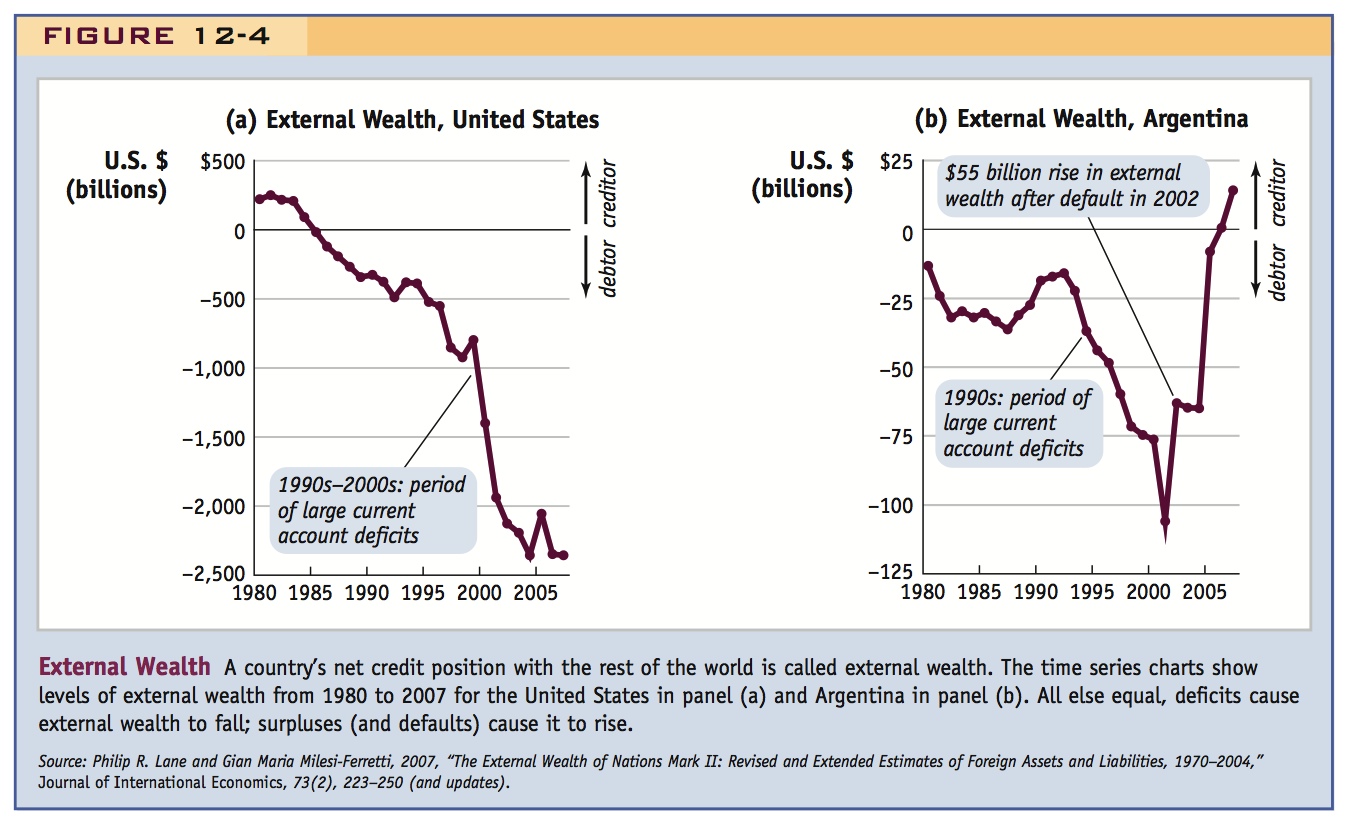

Changes in a nation’s external wealth can result from imbalances in its current account: external wealth rises when a nation has a surplus, and falls when it has a deficit, all else equal. For example, a string of U.S. current account deficits, going back to the 1980s, has been a major factor in the steady decline in U.S. external wealth, as shown in Figure 12-4, panel (a). The United States was generally a creditor nation until the mid-1980s when it became a debtor nation. More recently, by the end of 2012, the United States was the world’s largest debtor, with external wealth equal to −$4,416 billion.5 Argentina, another country with persistent current account deficits in the 1990s, also saw its external wealth decline, as panel (b) shows.

Emphasize that wealth can change for both of these reasons.

A closer look at these figures shows that there must be other factors that affect external wealth besides expenditure and income. For example, in years in which the United States ran deficits, its external wealth sometimes went up, not down. How can this be? Let us return to the household analogy. If you have ever invested in the stock market, you may know that even in a year when your expenditure exceeds your income, you may still end up wealthier because the value of your stocks has risen. For example, if you run a deficit of $1,000, but the value of your stocks rises by $10,000, then, on net, you are $9,000 wealthier. If the stocks’ value falls by $10,000, your wealth will fall by $11,000. Again, what is true for households is true for countries: their external wealth can be affected by capital gains (or, if negative, capital losses) on investments, so we need to think carefully about the complex causes and consequences of external wealth.

We also have to remember that a country can gain not only by having the value of its assets rise but also by having the value of its liabilities fall. Sometimes, liabilities fall because of market fluctuations; at other times they fall as a result of a deliberate action such as a nation deciding to default on its debts. For example, in 2002 Argentina announced a record default on its government debt by offering to pay about 30¢ for each dollar of debt in private hands. The foreigners who held most of this debt lost about $55 billion. At the same time, Argentina gained about $55 billion in external wealth, as shown by the sudden jump in Figure 12-4, panel (b). Thus, you don’t have to run a surplus to increase external wealth—external wealth rises not only when creditors are paid off but also when they are blown off.

12

Key Topics What forms can a nation’s external wealth take and does the composition of wealth matter? What explains the level of a nation’s external wealth and how does it change over time? How important is the current account as a determinant of external wealth? How does it relate to the country’s present and future economic welfare?

Darlings and Deadbeats: Defaults and Other Risks

The 2002 Argentine government’s debt default was by no means unusual. The following countries (among many others) have defaulted (sometimes more than once) on private creditors since 1980: Argentina (twice), Chile, Dominican Republic (twice), Ecuador, Greece, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru (twice), Philippines, Russia (twice), South Africa (twice), Ukraine, and Uruguay (twice).6 Dozens more countries could be added to the list if we expanded the definition of default to include the inability to make payments on loans from international financial institutions like the World Bank. (These debts may be continually rolled over, thus avoiding default by a technicality. In some cases, such loans are eventually forgiven, so they do not fall into the “default” category.)

13

Remind them that this is what makes sovereign debt different from private.

Defaults highlight a peculiar risk of international finance: creditors may be poorly protected in foreign jurisdictions. Sovereign governments can repudiate debt without legal penalty or hurt creditors in other ways such as by taking away their assets or changing laws or regulations after investments have already been made.

International investors try to avoid these risks as much as possible by careful assessment and monitoring of debtors. For example, any financial misbehavior by a nation or firm usually ends up on a credit report: a “grade A” credit score means easy access to low-interest loans; a “grade C” score means more limited credit and very high interest rates. Advanced countries usually have good credit ratings, but emerging markets often find themselves subject to lower ratings.

In one important type of credit rating, countries are also rated on the quality of the bonds they issue to raise funds. Such bonds are rated by agencies such as Standard & Poor’s (S&P): bonds rated BBB− or higher are considered high-grade or investment-grade bonds and bonds rated BB+ and lower are called junk bonds. Poorer ratings tend to go hand in hand with higher interest rates. The difference between the interest paid on a safe “benchmark” U.S. Treasury bond and the interest paid on a bond issued by a nation associated with greater risk is called country risk. Thus, if U.S. bonds pay 3% and another country pays 5% per annum on its bonds, the country risk is +2%.

For example, on September 28, 2012, the Financial Times reported that relatively good investment-grade governments such as Poland (grade A−) and Brazil (BBB) carried a country risk of +1.15% and +0.67% respectively, relative to U.S. Treasuries. Governments with junk grades such as Indonesia (grade BB+) and Turkey (BB) had to pay higher interest rates, with a country risk of 1.66% and 2.69%, respectively. Finally, Argentina, a country still technically in default, had bonds trading so cheaply (unrated, and considered beyond junk) they carried a massive +58% of country risk.

Key Topics Why do countries default? And what happens when they do? What are the determinants of risk premiums? How do risk premiums affect macroeconomic outcomes such as output, wealth, and exchange rates?

Summary and Plan of Study

International flows of goods, services, income, and capital allow the global macroeconomy to operate. In our course of study, we build up our understanding gradually, starting with basic accounting and measurement, then moving on to the causes and consequences of imbalances in the flows and the accumulations of debts and credits. Along the way, we learn about the gains from financial globalization, as well as some of its potential risks.

In Chapter 16, we learn how international transactions enter into a country’s national income accounts. Chapter 17 considers the helpful functions that imbalances can play in a well-functioning economy in the long run, and shows us the potential long-run benefits of financial globalization. Chapter 18 then explores how imbalances play a role in short-run macroeconomic adjustment and in the workings of the monetary and fiscal policies that are used to manage a nation’s aggregate demand. In Chapter 19, we learn that assets traded internationally are often denominated in different currencies and see how wealth can be sensitive to exchange rate changes and what macroeconomic effects this might have. Chapter 20 examines the implications of risk premiums for exchange rates, and shows that exchange rate crises and default crises are linked. Chapter 22 explores in more detail topics such as global imbalances and default.

14