5 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes

The monetary approach emphasizes that all nominal magnitudes—money, prices, and exchange rates—are inextricably linked. This raises important issues of policy design: Central banks adopt a long-run nominal anchor to maintain long-run price stability, but often grant themselves short run flexibility. Long-run anchoring and short-run flexibility characterize the monetary regime.

1. The Long Run: The Nominal Anchor

Three main types of anchors:

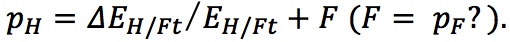

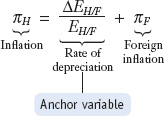

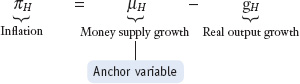

a. Exchange Rate Target: Rewrite relative PPP as  Then to control inflation use the expected rate of depreciation (e.g., a peg, or a crawl, or bands) as the anchor. Problem: The economy may be subject to foreign inflation shocks. Most pegs are relative to a currency known for its stability.

Then to control inflation use the expected rate of depreciation (e.g., a peg, or a crawl, or bands) as the anchor. Problem: The economy may be subject to foreign inflation shocks. Most pegs are relative to a currency known for its stability.

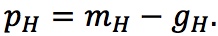

b. Money Supply Target: From the quantity theory  Use the money growth rate as the anchor. Here variations in real growth can drive inflation—too high in downturns, too low in expansions. Money targets aren’t used much anymore.

Use the money growth rate as the anchor. Here variations in real growth can drive inflation—too high in downturns, too low in expansions. Money targets aren’t used much anymore.

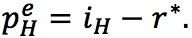

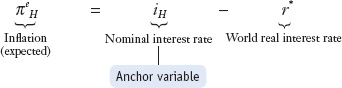

c. Inflation Target Plus Interest Rate Policy: From Fisher  Use the nominal interest rate as the anchor. Appealing if world real rates are stable, so commonly used now. Also allows short run flexibility in changing nominal rates.

Use the nominal interest rate as the anchor. Appealing if world real rates are stable, so commonly used now. Also allows short run flexibility in changing nominal rates.

2. The Choice of a Nominal Anchor and Its Implications

Two observations: (1) Under fixed rates, no other anchor can be used. However, adopting an intermediate regime permits a mix of different anchors. (2) Any anchor is a way for the central bank to commit to future monetary policies that achieve the desired target. Therefore any anchor surrenders monetary autonomy in the long run.

The monetary approach shows that, in the long run, all nominal variables—the money supply, interest rate, price level, and exchange rate—are interlinked. Hence, monetary policy choices can radically affect some important economic outcomes, notably prices and inflation, about which policy makers, governments, and the people they represent deeply care. The approach therefore highlights issues that must be taken into account in long-run economic policy design, and we will explore these important connections between theory and policy in this final section of the chapter.

We have repeatedly stressed the importance of inflation as an economic variable. Why is it so important? High or volatile inflation rates are considered undesirable. They may destabilize an economy or retard its growth.12 Economies with low and stable inflation generally grow faster than those with high or volatile inflation. Inflationary crises, in which inflation jumps to a high or hyperinflationary level, are very damaging indeed.13

Motivate the importance of a nominal anchor, and explain that fixed rates are often adopted in order to serve this function.

Thus, an overarching aspect of a nation’s economic policy is the desire to keep inflation within certain bounds. The achievement of such an objective requires that policy makers be subject to (or subject themselves to) some kind of constraint in the long run. Such constraints are called nominal anchors because they attempt to tie down a nominal variable that is potentially under the policy makers’ control.

Policy makers cannot directly control prices, so the attainment of price stability in the short run is not feasible. The question is what can policy makers do to promote price stability in the long run and what types of flexibility, if any, they will allow themselves in the short run. Long-run nominal anchoring and short-run flexibility are the characteristics of the policy framework that economists call the monetary regime. In this section, we examine different types of monetary regimes and what they mean for the exchange rate.

100

The Long Run: The Nominal Anchor

Explain each of the three types of anchors and their limitations. Argue that fixed rates may not even be the best choice, since they risk importing inflation.

Which variables could policy makers use as anchors to achieve an inflation objective in the long run? To answer this key question, all we have to do is go back and rearrange the equations for relative PPP at Equation (3-2), the quantity theory in rates of change at Equation (3-6), and the Fisher effect at Equation (3-8), to obtain alternative expressions for the rate of inflation in the home country. To emphasize that these findings apply generally to all countries, we re-label the countries Home (H) and Foreign (F) instead of United States and Europe.

The three main nominal anchor choices that emerge are as follows:

- Exchange rate target: Relative PPP at Equation (3-2) says that the rate of depreciation equals the inflation differential, or ΔEH/F/EH/F = πH − πF. Rearranging this expression suggests one way to anchor inflation is as follows:

Relative PPP says that home inflation equals the rate of depreciation plus foreign inflation. A simple rule would be to set the rate of depreciation equal to a constant. Under a fixed exchange rate, that constant is set at zero (a peg). Under a crawl, it is a nonzero constant. Alternatively, there may be room for movement about a target (a band). Or there may be a vague goal to allow the exchange rate “limited flexibility.” Such policies can deliver stable home inflation if PPP works well and if policy makers keep their commitment. The drawback is the final term in the equation: PPP implies that over the long run the home country “imports” inflation from the foreign country over and above the chosen rate of depreciation. For example, under a peg, if foreign inflation rises by 1% per year, then so, too, does home inflation. Thus, countries almost invariably peg to a country with a reputation for price stability (e.g., the United States). This is a common policy choice: fixed exchange rates of some form are in use in more than half of the world’s countries.

- Money supply target: The quantity theory suggests another way to anchor because the fundamental equation for the price level in the monetary approach says that inflation equals the excess of the rate of money supply growth over and above the rate of real income growth:

A simple rule of this sort is: set the growth rate of the money supply equal to a constant, say, 2% a year. The printing presses should be put on automatic pilot, and no human interference should be allowed. Essentially, the central bank is run by robots. This would be difficult to implement. Again the drawback is the final term in the previous equation: real income growth can be unstable. In periods of high growth, inflation will be below the desired level. In periods of low growth, inflation will be above the desired level. For this reason, money supply targets are waning in popularity or are used in conjunction with other targets. For example, the European Central Bank claims to use monetary growth rates as a partial guide to policy, but nobody is quite sure how serious it is.

- Inflation target plus interest rate policy: The Fisher effect suggests yet another anchoring method:

The Fisher effect says that home inflation is the home nominal interest rate minus the foreign real interest rate. If the latter can be assumed to be constant, then as long as the average home nominal interest rate is kept stable, inflation can also be kept stable. This type of nominal anchoring framework is an increasingly common policy choice. Assuming a stable world real interest rate is not a bad assumption. (And in principle, the target level of the nominal interest rate could be adjusted if necessary.) More or less flexible versions of inflation targeting can be implemented. A central bank could in theory set the nominal interest rate at a fixed level at all times, but such rigidity is rarely seen and central banks usually adjust interest rates in the short run to meet other goals. For example, if the world real interest rate is r* = 2.5%, and the country’s long-run inflation target is 2%, then its long-run nominal interest rate ought to be on average equal to 4.5% (because 2.5% = 4.5% − 2%). This would be termed the neutral level of the nominal interest rate. But in the short run, the central bank might desire to use some flexibility to set interest rates above or below this neutral level. How much flexibility is a matter of policy choice, as is the question of what economic objectives should drive deviations from the neutral rate (e.g., inflation performance alone, or other factors like output and employment that we shall consider in later chapters).

In fact, argue that a flexible interest rate rule might be better than either fixed rates or a money rule.

The Choice of a Nominal Anchor and Its Implications Under the assumptions we have made, any of the three nominal anchor choices are valid. If a particular long-run inflation objective is to be met, then, all else equal, the first equation says it will be consistent with one particular rate of depreciation; the second equation says it will be consistent with one particular rate of money supply growth; the third equation says it will be consistent with one particular rate of interest. But if policy makers announced targets for all three variables, they would be able to match all three consistently only by chance. Two observations follow.

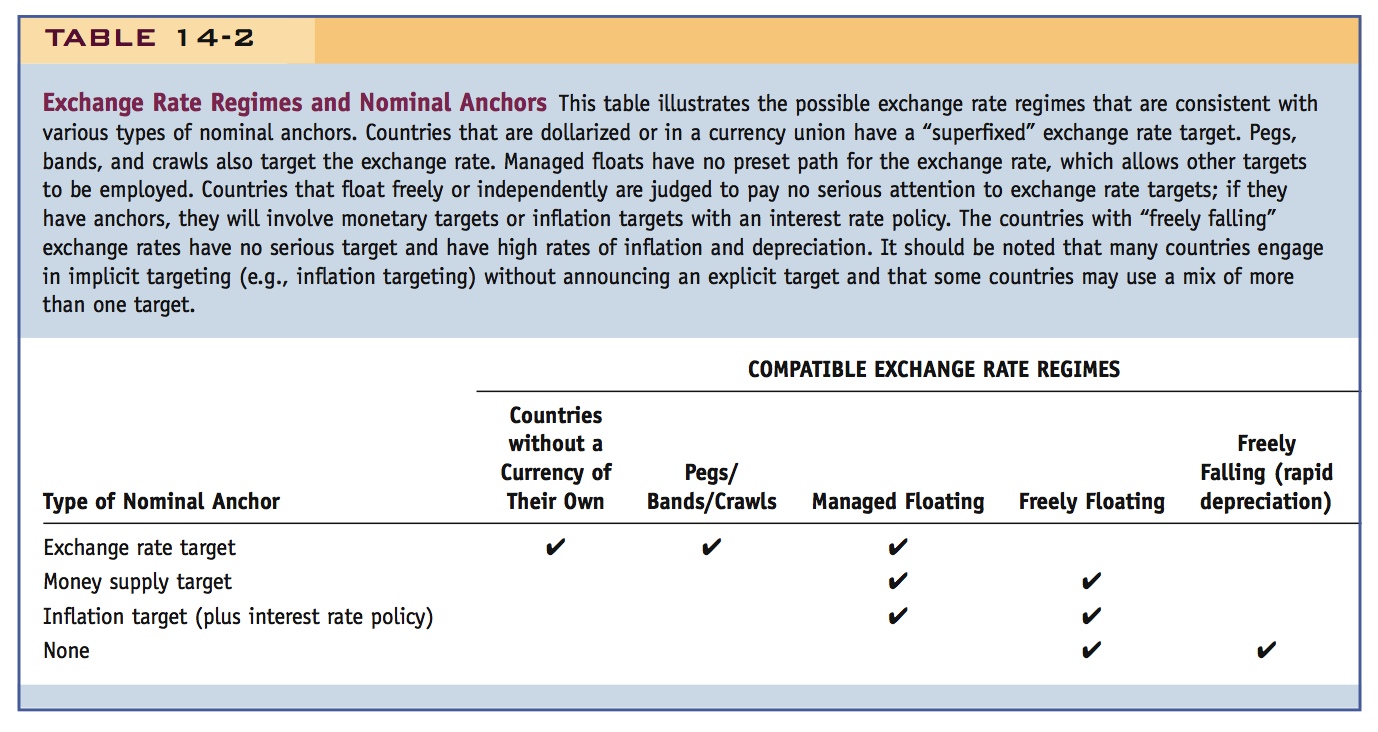

First, using more than one target may be problematic. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, policy makers cannot employ any target other than the exchange rate. However, they may be able to use a mix of different targets if they adopt an intermediate regime, such as a managed exchange rate with limited flexibility. Table 14-2 illustrates the ways in which the choice of a target as a nominal anchor affects the choice of exchange rate regime. Obviously, these are not independent choices. But a variety of choices do exist. Thus, nominal anchoring is possible with a variety of exchange rate regimes.

102

A deep point: Every nominal anchor achieves price stability by surrendering monetary autonomy in the long run.

Second, whatever target choice is made, a country that commits to a target as a way of nominal anchoring is committing itself to set future money supplies and interest rates in such a way as to meet the target. Only one path for future policy will be compatible with the target in the long run. Thus, a country with a nominal anchor sacrifices monetary policy autonomy in the long run.

A brief history of monetary regimes and anchors since the Great Inflation.

Note the trend towards central bank independence, perhaps epitomized by the ECB.

Nominal Anchors in Theory and Practice

An appreciation of the importance of nominal anchors has transformed monetary policy making and inflation performance throughout the global economy in recent decades.

In the 1970s, most of the world was struggling with high inflation. An economic slowdown prompted central banks everywhere to loosen monetary policy. In advanced countries, a move to floating exchange rates allowed great freedom for them to loosen their monetary policy. Developing countries had already proven vulnerable to high inflation and now many of them were exposed to even worse inflation. Those who were pegged to major currencies imported high inflation via PPP. Those who weren’t pegged struggled to find a credible nominal anchor as they faced economic downturns of their own. High oil prices everywhere contributed to inflationary pressure.

103

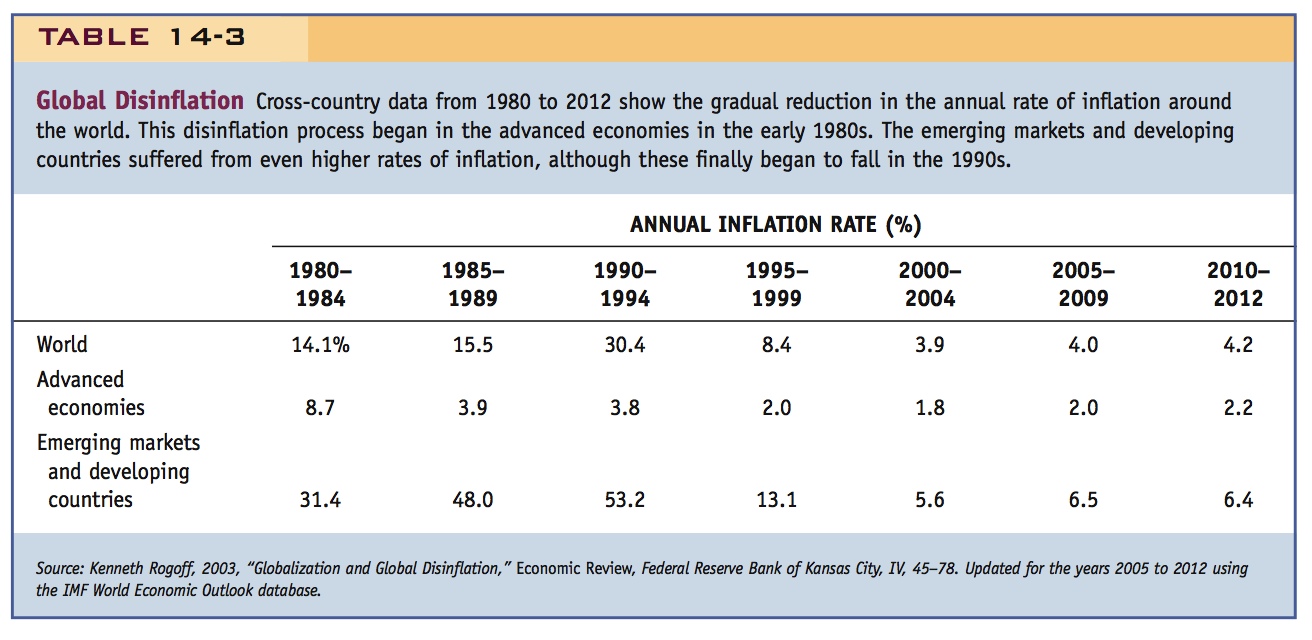

In the 1980s, inflationary pressure continued in many developed countries, and in many developing countries high levels of inflation, and even hyperinflations, were not uncommon. Governments were forced to respond to public demands for a more stable inflation environment. In the 1990s, policies designed to create effective nominal anchors were put in place in many countries, and these have endured to the present.

One study found that the use of explicit targets grew markedly in the 1990s, replacing regimes in which there had previously been no explicit nominal anchor. The number of countries in the study with exchange rate targets increased from 30 to 47. The number with money targets increased from 18 to 39. The number with inflation targets increased most dramatically, almost sevenfold, from 8 to 54. Many countries had more than one target in use: in 1998, 55% of the sample announced an explicit target (or monitoring range) for more than one of the exchange rate, money, and inflation. These shifts have persisted. As of 2010, more than a decade later, there were still more than 50 inflation-targeting countries (many now part of the single Eurozone block), and there were more than 80 countries pursuing some kind of exchange rate target via a currency board, peg, band or crawl type arrangement.14

Looking back from the present we can see that most, but not all, of those policies have turned out to be credible, too, thanks to political developments in many countries that have fostered central bank independence. Independent central banks stand apart from the interference of politicians: they have operational freedom to try to achieve the inflation target, and they may even play a role in setting that target.

Overall, these efforts are judged to have achieved some success, although in many countries inflation had already been brought down substantially in the early to mid-1980s before inflation targets and institutional changes were implemented. Table 14-3 shows a steady decline in average levels of inflation since the early 1980s. The lowest levels of inflation are seen in the advanced economies, although developing countries have also started to make some limited progress. In the industrial countries, central bank independence is now commonplace (it was not in the 1970s), but in developing countries it is still relatively rare.

104

Still, one can have too much of a good thing, and the crisis of 2008–2010 prompted some second thoughts about inflation targets. Typically, such targets have been set at about 2% in developed countries, and with a world real interest rate of 2% this implies a neutral nominal interest rate of 4%. In terms of having room to maneuver, this rate permits central banks to temporarily cut their interest rates up to four percentage points below the neutral level. Prior to the crisis this range was considered ample room for central banks to take short-run actions as needed (e.g., to stimulate output or the rate of inflation if either fell too low). In the crisis, however, central banks soon hit the lower bound of zero rates and could not prevent severe output losses and declines in inflation rates to low or, at times, negative levels (deflation). As Irving Fisher famously noted, deflation is very damaging economically—it drives up real interest rates when nominal rates can fall no further as an offset, and falling prices make the real burden of nominal debts higher. These problems have led some economists, among them the IMF’s Chief Economist, Olivier Blanchard, to question whether inflation targets should be set higher (e.g., at 4% rather than 2%).15 The idea received a lukewarm reception, however: moving to a higher inflation target is easy in principle, but many feared its potential abuse would risk the hard-won credibility gains that central banks have earned for themselves in the last three decades. Indeed, even as inflation rates fell almost to zero in major economies like the United States and Eurozone, many central bankers continued to speak of their vigilance in guarding against inflation.