3 The Balance of Payments

The CA = TB + NFIA + NUT summarizes transaction in goods, services, factor services, and transfers. Now look at transactions in assets, which finance CA imbalances.

1. Accounting for Asset Transactions: The Financial Account

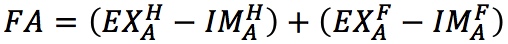

Assets include real as well as financial assets issued by firms, governments, or households. A country can export assets or import them. Then the financial account is net exports of home assets,

FA = EXA - IMA.

2. Accounting for Asset Transactions: The Capital Account

The KA includes nonfinancial, nonproduced assets (e.g., patents or copyrights) and debt forgiveness. It is very small for most developed countries.

3. Accounting for Home and Foreign Assets

Importing a foreign asset means we are acquiring an obligation from the other country; exporting an asset means we are incurring an obligation or liability to the other country (we are borrowing). Therefore  means FA =net additions to home liabilities – net additions to external liabilities. Asset accumulation will affect a nation’s wealth.

means FA =net additions to home liabilities – net additions to external liabilities. Asset accumulation will affect a nation’s wealth.

4. How the Balance of Payments Accounts Work: A Macroeconomic View

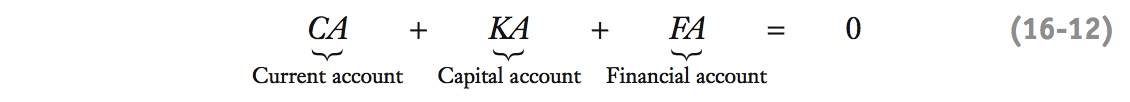

BOP = CA + KA + FA = 0, so the BOP is identically zero. CA deficits must be financed with FA surpluses (borrowing).

5. How the Balance of Payments Accounts Work: A Microeconomic View

Transactions that generate payments from the rest of the world (ROW) are credits; transactions that generate payments to the ROW are debits. Every debit creates a corresponding credit, and vice versa. Therefore the BOP is identically zero.

In the previous section, we saw that the current account summarizes the flow of all international market transactions in goods, services, and factor services plus nonmarket transfers. In this section, we look at what’s left: international transactions in assets. These transactions are of great importance because they tell us how the current account is financed and, hence, whether a country is becoming more or less indebted to the rest of the world. We begin by looking at how transactions in assets are accounted for, once again building on the intuition developed in Figure 16-2.9

Accounting for Asset Transactions: The Financial Account

Here too, they should have the basic idea already from Section 1. Just emphasize key points that may need elaboration.

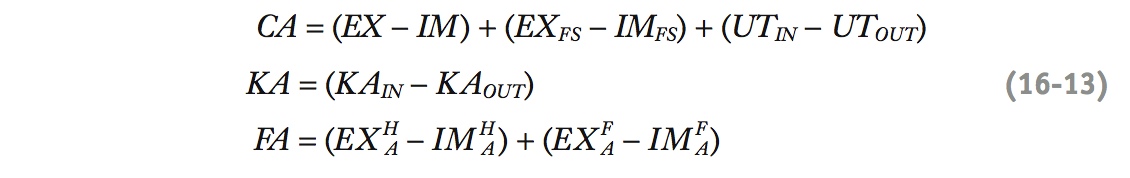

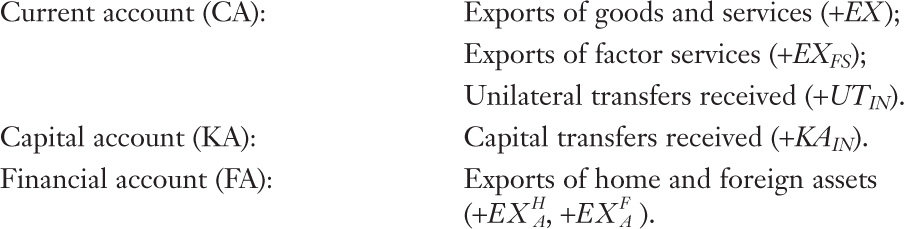

The financial account (FA) records transactions between residents and nonresidents that involve financial assets. The total value of financial assets that are received by the rest of the world from the home country is the home country’s export of assets, denoted EXA (the subscript “A” stands for asset). The total value of financial assets that are received by the home country from the rest of the world in all transactions is the home country’s import of assets, denoted IMA.

The financial account measures all “movement” of financial assets across the international border. By this, we mean a movement from home to foreign ownership, or vice versa, even if the assets do not physically move. This definition also covers all types of assets: real assets such as land or structures, and financial assets such as debt (bonds, loans) or equity. The financial account also includes assets issued by any entity (firms, governments, households) in any country (home or overseas). Finally, the financial account includes market transactions as well as transfers, or gifts of assets.

Subtracting asset imports from asset exports yields the home country’s net overall balance on asset transactions, which is known as the financial account, where FA = EXA − IMA. A negative FA means that the country has imported more assets than it has exported; a positive FA means the country has exported more assets than it has imported. The financial account therefore measures how the country can increase or decrease its holdings of assets through international transactions.

Accounting for Asset Transactions: The Capital Account

The capital account (KA) covers some remaining, minor activities in the balance of payments account. One is the acquisition and disposal of nonfinancial, nonproduced assets (e.g., patents, copyrights, trademarks, franchises, etc.). These assets have to be included here because such nonfinancial assets do not appear in the financial account, although like financial assets, they can be bought and sold with resulting payments flows. The other important item in the capital account is capital transfers (i.e., gifts of assets), an example of which is the forgiveness of debts.10

179

As with unilateral income transfers, capital transfers must be accounted for properly. For example, the giver of an asset must deduct the value of the gift in the capital account to offset the export of the asset, which is recorded in the financial account, because in the case of a gift the export generates no associated payment. Similarly, recipients of capital transfers need to record them to offset the import of the asset recorded in the financial account.

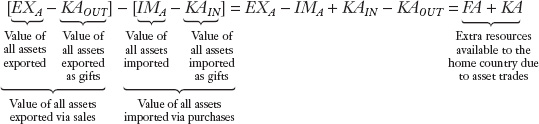

Using similar notation to that employed with unilateral transfers of income, we denote capital transfers received by the home country as KAIN and capital transfers given by the home country as KAOUT. The capital account, K A = KAIN − KAOUT, denotes net capital transfers received. A negative KA indicates that more capital transfers were given by the home country than it received; a positive KA indicates that the home country received more capital transfers than it made.

The capital account is a minor and technical accounting item for most developed countries, usually close to zero. In some developing countries, however, the capital account can at times play an important role because in some years nonmarket debt forgiveness can be large, whereas market-based international financial transactions can be small.

Accounting for Home and Foreign Assets

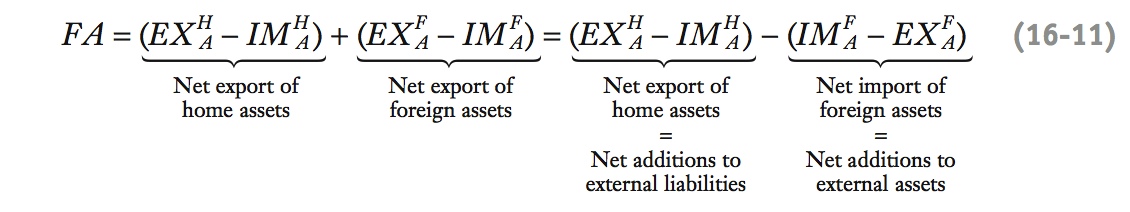

Asset trades in the financial account can be broken down into two types: assets issued by home entities (home assets) and assets issued by foreign entities (foreign assets). This is of economic interest, and sometimes of political interest, because the breakdown makes clear the distinction between the location of the asset issuer and the location of the asset owner, that is, who owes what to whom.

From the home perspective, a foreign asset is a claim on a foreign country. When a home entity holds such an asset, it is called an external asset of the home country because it represents an obligation owed to the home country by the rest of the world. Conversely, from the home country’s perspective, a home asset is a claim on the home country. When a foreign entity holds such an asset, it is called an external liability of the home country because it represents an obligation owed by the home country to the rest of the world. For example, when a U.S. firm invests overseas and acquires a computer factory located in Ireland, the acquisition is an external asset for the United States (and an external liability for Ireland). When a Japanese firm acquires an automobile plant in the United States, the acquisition is an external liability for the United States (and an external asset for Japan). A moment’s thought reveals that all other assets traded across borders have a nation in which they are located and a nation by which they are owned—this is true for bank accounts, equities, government debt, corporate bonds, and so on. (For some examples, see Side Bar: The Double-Entry Principle in the Balance of Payments.)

If we use superscripts “H” and “F” to denote home and foreign assets, we can break down the financial account as the sum of the net exports of each type of asset:

180

In the last part of this formula, we use the fact that net imports of foreign assets are just minus net exports of foreign assets, allowing us to change the sign. This reveals to us that FA equals the additions to external liabilities (the home-owned assets moving into foreign ownership, net) minus the additions to external assets (the foreign-owned assets moving into home ownership, net). This is our first indication of how flows of assets have implications for changes in a nation’s wealth, a topic to which we return shortly.

How the Balance of Payments Accounts Work: A Macroeconomic View

To further understand the links between flows of goods, services, income, and assets, we have to understand how the current account, capital account, and financial account are related and why, in the end, the balance of payments accounts must balance as seen in the open-economy circular flow (Figure 16-2).

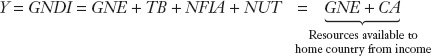

Recall from Equation (5-4) that gross national disposable income is

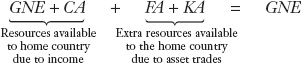

Does this expression represent all of the resources that are available to the home economy to finance expenditure? No. It represents only the income resources, that is, the resources obtained from the market sale and purchase of goods, services, and factor services and from nonmarket transfers. In addition, the home economy can free up (or use up) resources in another way: by engaging in net sales (or purchases) of assets. We can calculate these extra resources using our previous definitions:

Adding the last two expressions, we arrive at the value of the total resources available to the home country for expenditure purposes. This total value must equal the total value of home expenditure on final goods and services, GNE:

We can cancel GNE from both sides of this expression to obtain the important result known as the balance of payments identity or BOP identity:

This, for example, bears emphasis.

The balance of payments sums to zero: it does balance!

181

How the Balance of Payments Accounts Work: A Microeconomic View

We have just found that at the macroeconomic level, CA + KA + FA = 0, a very simple equation that summarizes, in three variables, every single one of the millions of international transactions a nation engages in. This is one way to look at the BOP accounts.

Another way to look at the BOP is to look behind these three variables to the specific flows we saw in Figure 16-2, and the individual transactions within each flow.

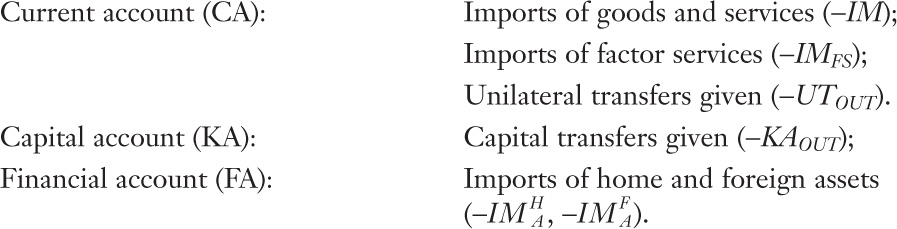

Written this way, the components of the BOP identity allow us to see the details behind why the accounts must balance. As you can observe from these equations, there are 12 transaction types (each preceded by either a plus or minus sign) and 3 accounts (CA, KA, FA) in which they can appear.

If an item has a plus sign, it is called a balance of payments credit, or BOP credit. Six types of transactions receive a plus (+) sign as follows:

If an item has a minus sign, it is called a balance of payments debit, or BOP debit. Six types of transactions receive a minus (−) sign as follows:

And this does too.

Now, to see why the BOP accounts balance overall, we have to understand one simple principle: every market transaction (whether for goods, services, factor services, or assets) has two parts. If party A engages in a transaction with a counterparty B, then A receives from B an item of a given value, and in return B receives from A an item of equal value.11

182

Thus, whenever a transaction generates a credit somewhere in the BOP account, it must also generate a corresponding debit somewhere else in the BOP account. Similarly, every debit generates a corresponding credit. (For more detail on this topic, see Side Bar: The Double-Entry Principle in the Balance of Payments.)

It might not be obvious where the offsetting item is, but it must exist somewhere if the accounts have been measured properly. As we shall see shortly, this is a big “if”: mismeasurement can sometimes be an important issue.

Have the students think up transactions and figure out how they'd be recored in the BOP.

Examples of how transactions are entered in the BOP. Always look for a credit to match the debit, or vice versa.

The Double-Entry Principle in the Balance of Payments

We can make the double-entry principle more concrete by looking at some (mostly) hypothetical international transactions and figuring out how they would be recorded in the U.S. BOP accounts.

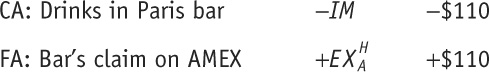

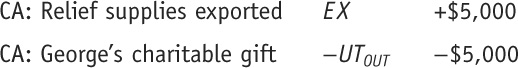

- Recall from Chapter 13 that our friend George was in Paris. Suppose he spent $110 (€100) on French wine one evening. This is a U.S. import of a foreign service. George pays with his American Express card. The bar is owed $110 (or €100) by American Express (and Amex is owed by George). The United States has exported an asset to France: the bar now has a claim against American Express. From the U.S. perspective, this represents an increase in U.S. assets owned by foreigners. The double entries in the U.S. BOP appear in the current account and the financial account:

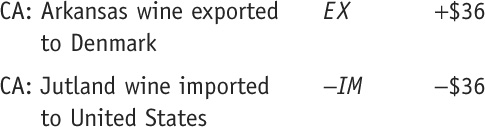

- George was in the bar to meet his Danish cousin Georg. They both work as wine merchants. After a few bottles of Bordeaux, George enthuses about Arkansas chardonnay and insists Georg give it a try. Georg counters by telling George he should really try some Jutland rosé. Each cousin returns home and asks his firm to ship a case of each wine (worth $36) to the other. This barter transaction (involving no financial activity) would appear solely as two entries in the U.S. current account:

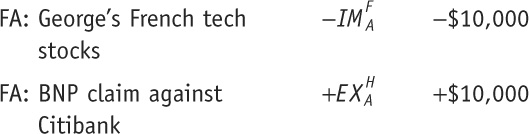

- Later that night, George met a French entrepreneur in a smoky corner of the bar. George vaguely remembers the story: the entrepreneur’s French tech company was poised for unbelievable success with an upcoming share issue. George decides to invest $10,000 to buy the French stock; he imports a French asset. The stock is sold to him through the French bank BNP, and George sends them a U.S. check. BNP then has a claim against Citibank, an export of a home asset to France. Both entries fall within the financial account:

- Rather surprisingly, George’s French stocks do quite well. Later that year they have doubled in value. George makes a $5,000 donation to charity. His charity purchases U.S. relief supplies that will be exported to a country suffering a natural disaster. The two entries here are entirely in the U.S. current account. The supplies are a nonmarket export of goods offset by the value of the unilateral transfer:

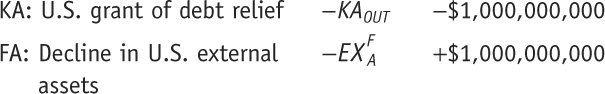

- George was also pleased to see that some poor countries were benefiting from another kind of foreign assistance, debt forgiveness. The U.S. Secretary of State announced that the United States would forgive $1 billion of debt owed by a developing country. This would decrease U.S.-owned assets overseas. The United States was exporting the developing country’s assets: it hands the canceled debts back, a credit in the financial account. The double entries would be seen in the capital and financial accounts:

183

Understanding the Data for the Balance of Payments Account

6.Understanding the Data for the Balance of Payments Account

A look at the U.S. BOP in 2012. The U.S. had a TB deficit, but earned net income (NFIA) from abroad. It ran a NUT deficit, so it was a net donor. The CA deficit is financed running an FA surplus, borrowing from the rest of the world. Note also: (1) Financial transactions are broken down into nonreserve and reserve components, of which the latter represents intervention in FX markets by central banks. (2) CA + FA + KA ≠ 0 because of the statistical discrepancy.

7.What the Balance of Payments Account Tells Us

The CA measures imbalances in goods, services, and transfers; the FA measures financial transactions. Surpluses on one side of the BOP must be offset by deficits on the other. CA imbalances imply borrowing or lending that will affect national wealth.

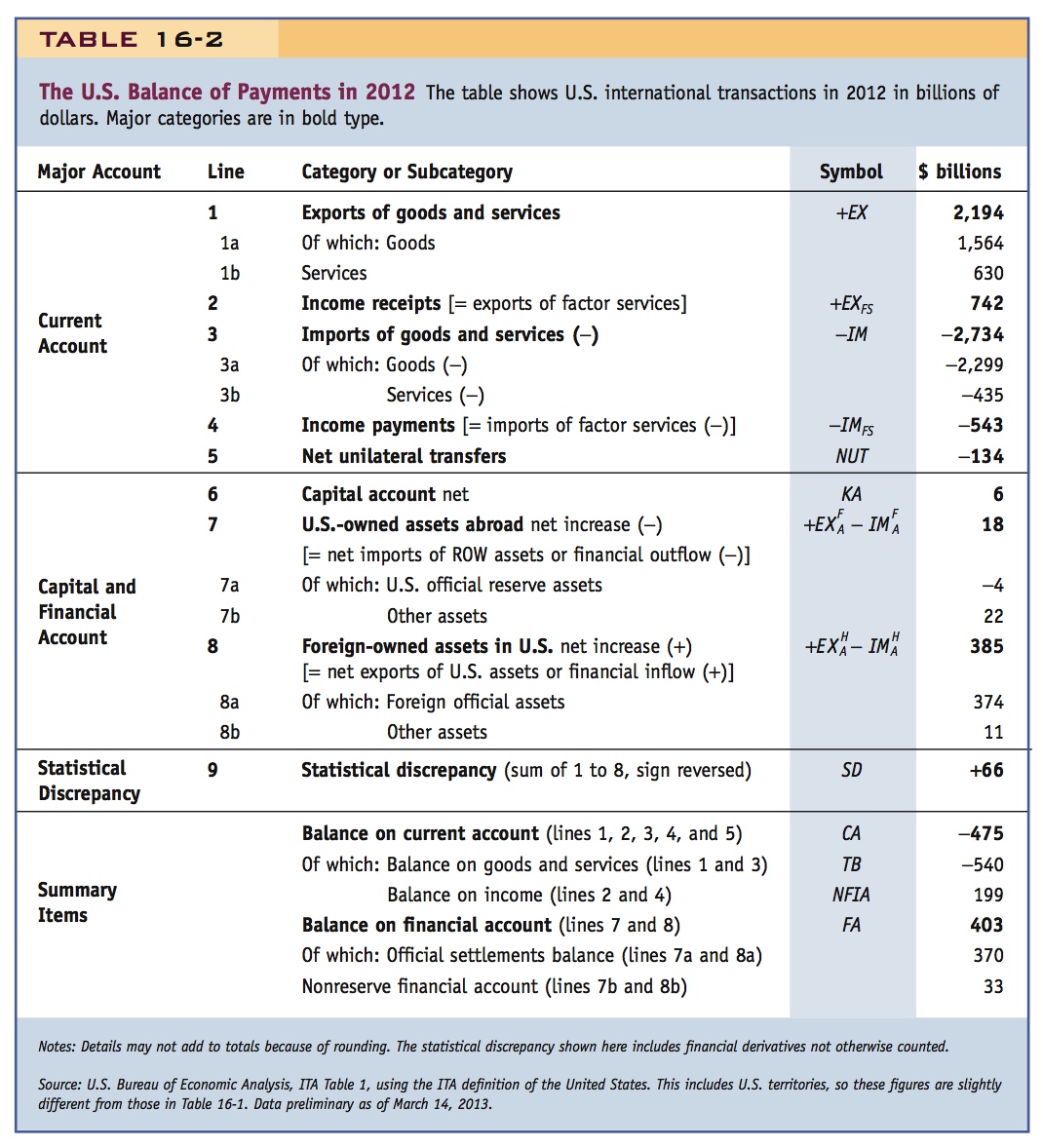

To illustrate all the principles we’ve learned, let’s look at the United States’ balance of payments account. Table 16-2 shows an extract of the U.S. BOP accounts for 2012.12

In the current account, in the top part of the table, we look first at the trade in goods and services on lines 1 and 3. Overall exports EX were +$2,194 billion (line 1, a credit), and imports IM were −$2,734 billion (line 3, a debit). In the summary items, we see the balance on goods and services, the trade balance TB, was −$540 billion (line 1 plus line 3, or exports minus imports). Exports and imports and the trade balance are also broken down even further into goods and service components (lines 1a, 1b, 3a, and 3b).

184

The next part of the current account on lines 2 and 4 deals with trade in factor services, also known as the income account (referring to the income paid to those factors). Income receipts for factor service exports, EXFS, generated a credit of +$742 billion and income payments for factor service imports, IMFS, generated a debit of −$543 billion. Adding these two items resulted in net factor income from abroad NFIA equal to +$199 billion (line 2 plus line 4), a net credit.

Lastly, we see that net unilateral transfers NUT were −$134 billion, a net debit (line 5); the United States was a net donor as measured by the net transfer of goods, services, and income to the rest of the world. (Typically, in summary tables like these, unilateral transfers are shown only in net form.)

Overall, summing lines 1 through 5, the 2012 U.S. current account balance CA was −$475 billion, that is, a deficit of $475 billion, as shown in the summary items at the foot of the table.

Emphasize again that CA surpluses (deficits) imply lending (borrowing).

A country with a current account surplus is called a (net) lender. By the BOP identity, we know that it must have a deficit in its asset accounts, so like any lender, it is, on net, buying assets (acquiring IOUs from borrowers). For example, China is a large net lender. A country with a current account deficit is called a (net) borrower. By the BOP identity, we know that it must have a surplus in its asset accounts, so like any borrower, it is, on net, selling assets (issuing IOUs to lenders). As we can see, the United States is a large net borrower.

Now we move to the capital and financial accounts. Typically, in summary tables like these, the capital account is shown only in net form. The United States in 2012 had a negligible capital account KA of +$6 billion (line 6).

Lastly, we move to the financial account. As explained, this account can be broken down in terms of the exports and imports of two kinds of assets: U.S. assets (U.S. external liabilities) and rest of the world assets (U.S. external assets). In this summary the net trades are shown for each kind of asset.

We see that the United States was engaged in the net sale of foreign assets, so that external assets (U.S.-owned assets abroad) decreased by $18 billion. This net export of foreign assets is recorded as a credit of +$18 billion (line 7). Note that the plus sign maintains the convention that exports are credits.

So that the CA deficit of the U.S. is offset by a FA surplus.

At the same time, the United States was engaged in the net export of U.S. assets to the rest of the world so that external liabilities (foreign-owned assets in the United States) increased by $385 billion; the net export of U.S. assets is duly recorded as a credit of +$385 billion (line 8).

The sum of lines 7 and 8 gives the financial account balance FA of +$403 billion, recorded in the summary items.

Explain how FX intervention enters here.

For further information on interventions by central banks, financial account transactions are often also broken down into reserve and nonreserve components. Changes in reserves arise from official intervention in the foreign exchange market—that is, purchases and sales by home and foreign monetary authorities. The balance on all reserve transactions is called the official settlements balance, and the balance on all other asset trades is called the nonreserve financial account. We see here that U.S. authorities intervened a little: a net import of $4 billion of U.S. official reserves (line 7a) means that the Federal Reserve bought $4 billion in foreign (i.e., nondollar) exchange reserves from foreigners. In contrast, foreign central banks intervened a lot: U.S. entities sold them $374 billion in U.S. dollar reserve assets (line 8a).

185

Adding up the current account, the capital account, and the financial account (lines 1 through 8), we find that the total of the three accounts was −$66 billion (−$475 + $6 + $403 = −$66). The BOP accounts are supposed to balance by adding to zero—in reality, they never do. Why not? Because the statistical agencies tasked with gathering BOP data find it impossible to track every single international transaction correctly, because of measurement errors and omissions. Some problems result from the smuggling of goods or trade tax evasion. Larger errors are likely due to the mismeasured, concealed, or illicit movement of financial income flows and asset movements (e.g., money laundering and capital tax evasion).

The Statistical Discrepancy To “account” for this error, statistical agencies create an accounting item, the statistical discrepancy (SD) equal to minus the error SD = −(CA + KA + FA). With that “correction,” the amended version of the BOP identity will hold true in practice, sweeping away the real-world measurement problems. In the table, the statistical discrepancy is shown on line 9.13 Once the statistical discrepancy is included, the balance of payments accounts always balance.

Go back to CA = S - I to explain these changes.

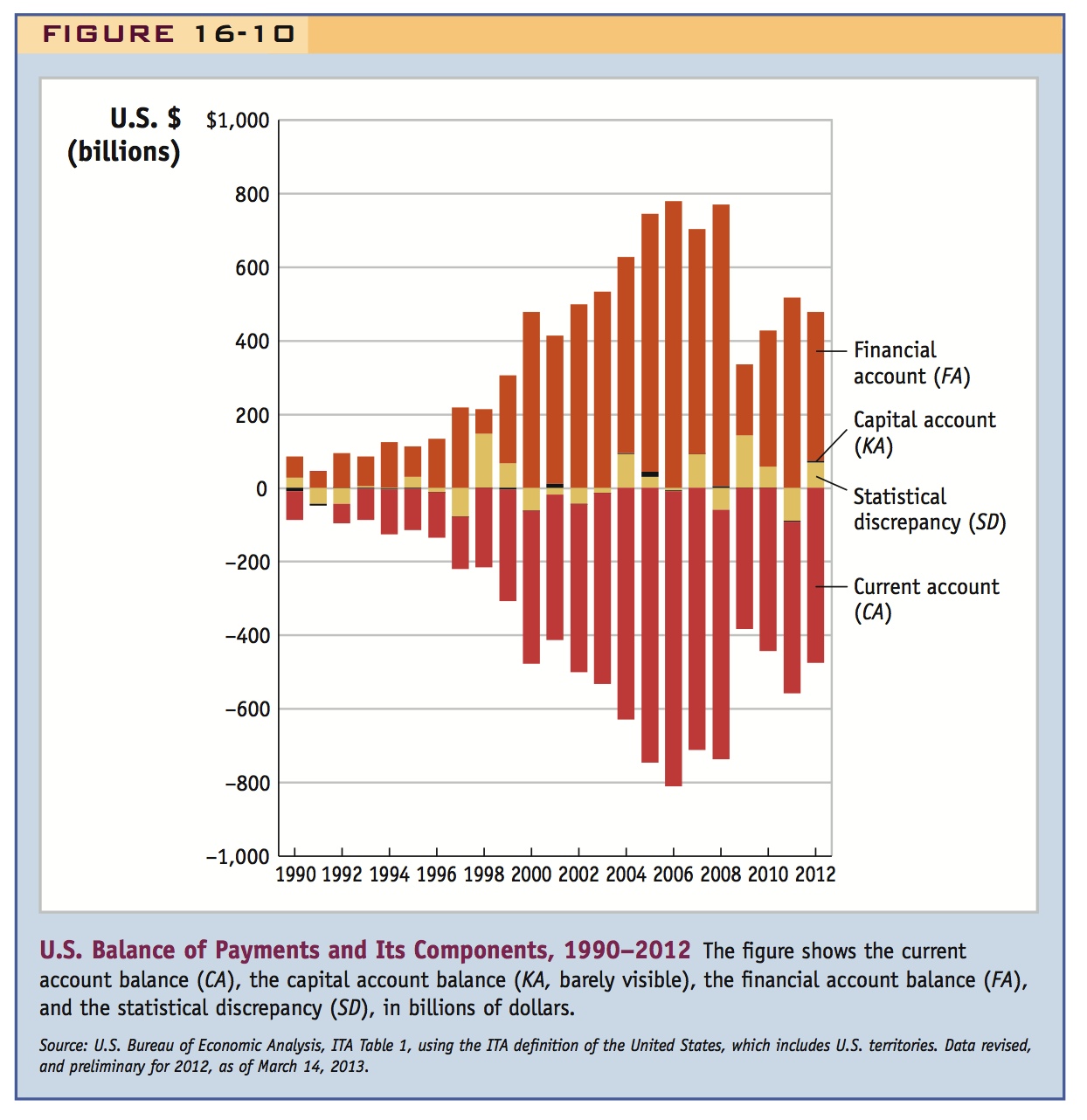

Some Recent Trends in the U.S. Balance of Payments Figure 16-10 shows recent trends in various components of the U.S. balance of payments. The sharp downward trend of the current account is as previously shown in Figure 16-6, so for the balance of payments identity to hold, there must be an offsetting upward trend in other parts of the BOP accounts. This is indeed the case. We can see that the United States has been financing its growing deficit on the current account primarily by running an expanding surplus on the financial account. In the mid-1990s, there was close to a $100 billion current account deficit and a comparable financial account surplus. A decade later, both figures were in the region of $800 billion, with a substantial decline seen in the period since the global financial crisis of 2008 and up to 2012.

What the Balance of Payments Account Tells Us

The balance of payments accounts consist of the following:

- The current account, which measures external imbalances in goods, services, factor services, and unilateral transfers.

- The financial and capital accounts, which measure asset trades.

Using the principle that market transactions must consist of a trade of two items of equal value, we find that the balance of payments accounts really do balance.

This is intuitive, but elaborate on it anyway: A CA surplus means we are lending, so our wealth will accumulate over time.

Surpluses on the current account side of the BOP accounts must be offset by deficits on the asset side. Similarly, deficits on the current account must be offset by surpluses on the asset side. By telling us how current account imbalances are financed, the balance of payments connects a country’s income and spending decisions to the evolution of that country’s wealth, an important connection we develop further in the final section of this chapter.

186