3 Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

So far we’ve looked at unilateral pegs to a single country. There are more complicated fixed exchange rate systems, with multiple countries. Examples include Bretton Woods and the ERM. These systems consist of N countries who adopt the reserve currency of the Nth country, called the center country. Examples: the U.S. in Bretton Woods, Germany in the ERM. Each noncenter country pegs to the center country, and so loses its control over monetary policy; the center country does not. This is a recipe for political conflict, and is called the Nth country problem. It may be alleviated through cooperative agreements.

1. Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Interest Rates

Suppose the noncenter country suffers an adverse demand shock. To prevent its currency from depreciating it must raise its interest rates, which pushes it even deeper into recession. Meanwhile the center country is unaffected. This is the noncooperative outcome. Consider instead a cooperative outcome: The center country agrees to lower its interest rate, so the noncenter country does too. This reduces expenditures in both countries, but this contractionary effect is offset by the expansionary monetary policies. Both countries see an increase in income. The center country has income slightly greater than what it would desire, but the noncenter country avoids recession.

a. Caveats

Why would countries cooperate? Both countries would like to have the benefits of the peg, but neither wants to unilaterally peg to the other, and thereby incur the stability costs of being the noncenter country. However, this is hard to implement in practice because countries often face asymmetric shocks. If the center country in our previous example is already overheating, for example, it may be reluctant to lower interest rates to help the noncenter country. The refusal of the Bundesbank to lower interest rates during the ERM crisis is a case in point. Conclusion: the center country usually doesn’t want to surrender its autonomy.

2. Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Exchange Rates

Now imagine two noncenter countries, Home and Foreign, relative to a center country, the U.S. As before, Home suffers a decline in demand, which is exacerbated by the increase in interest rates required to maintain the peg. Now suppose that there is a cooperative agreement for Home to devalue a little relative to Foreign (and the dollar). This raises Home income, but lowers Foreign income, so the pain is shared. Alternatively, Home could engage in a large, noncooperative devaluation that allows it to regain full employment. However, this would amount to exporting the recession to Foreign.

a. Caveats

Noncooperative devaluations are beggar-thy-neighbor policies that may elicit competitive devaluations by other countries. Cooperative devaluations may be needed to sustain the system, but they are hard to implement.

So far, our discussion has considered only the simplest type of fixed exchange rate: a single home country that unilaterally pegs to a foreign base country. In reality there are more complex arrangements, called fixed exchange rate systems, which involve multiple countries. Examples include the global Bretton Woods system, in the 1950s and 1960s, and the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), to which all members have to adhere for at least two years as a precondition to euro entry.

Fixed exchange rate systems like these are based on a reserve currency system in which N countries (1, 2, …, N) participate. The Nth country, called the center country, provides the reserve currency, which is the base or center currency to which all the other countries peg. In the Bretton Woods system, for example, N was the U.S. dollar; in the ERM, N was the German mark until 1999, and is now the euro.

Remind the students that we have already encountered this asymmetry in our discussion of Germany, Britain, and France in the ERM.

Throughout this chapter, we have assumed that a country pegs unilaterally to a center country, and we know that this leads to a fundamental asymmetry. The center country has monetary policy autonomy and can set its own interest rate i* as it pleases. The other noncenter country, which is pegging, then has to adjust its own interest rate so that i equals i* in order to maintain the peg. The noncenter country loses its ability to conduct stabilization policy, but the center country keeps that power. The asymmetry can be a recipe for political conflict and is known as the Nth currency problem.

Are these problems serious? And can a better arrangement be devised? In this section, we show that cooperative arrangements may be the answer. We study two kinds of cooperation. One form of cooperation is based on mutual agreement and compromise between center and noncenter countries on the setting of interest rates. The other form of cooperation is based on mutual agreements about adjustments to the levels of the fixed exchange rates themselves.

Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Interest Rates

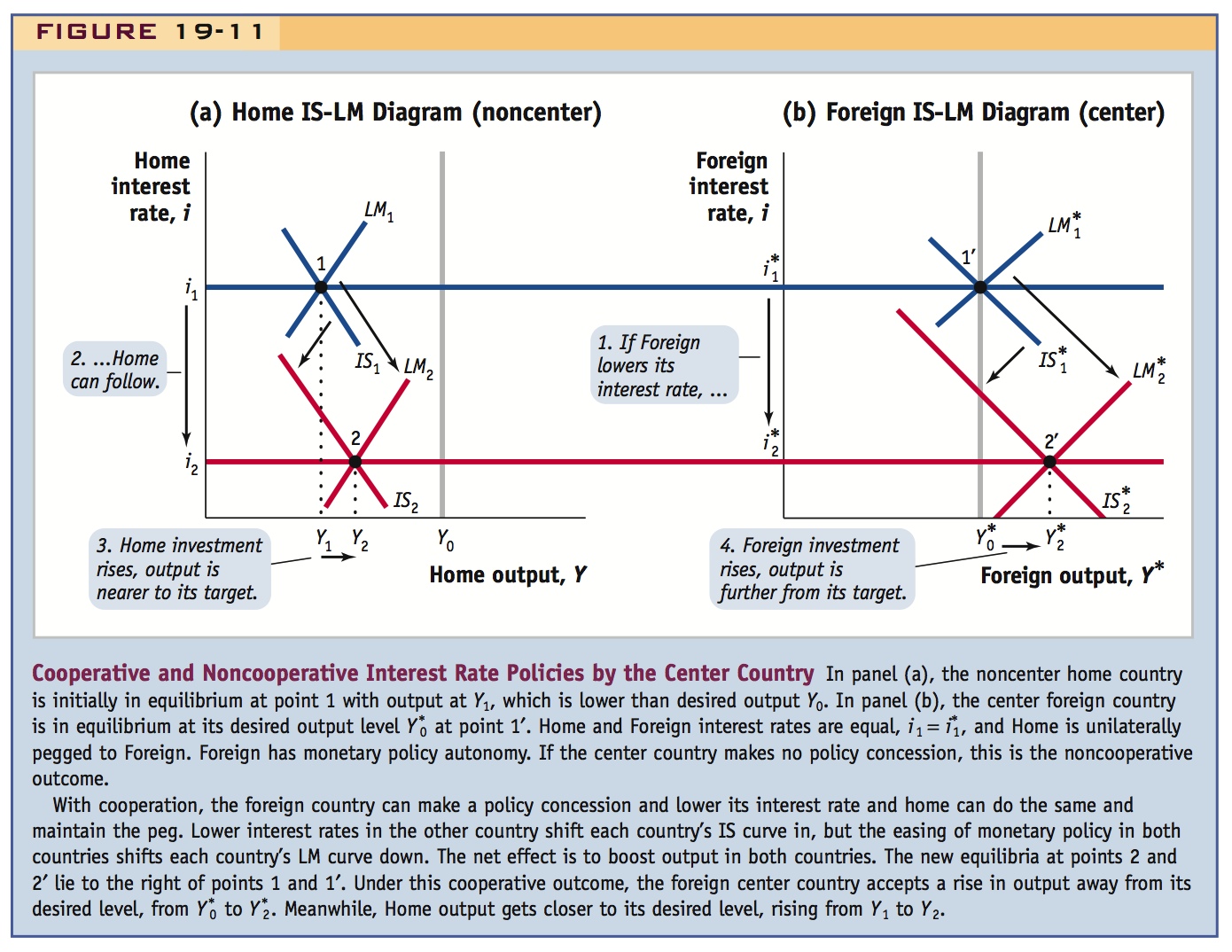

Figure 19-11, panel (a), illustrates the possibility of policy conflict between center and noncenter countries. Suppose that Home, which is the noncenter country, experiences an adverse demand shock, but Foreign, the center country, does not. We have studied this case before in the previous chapter: the Home IS curve shifts left and the Home LM curve then must shift up to maintain the peg and ensure that the Home interest rate i is unchanged and equal to i*.

We now assume that these shifts have already occurred, and we start the analysis with the Home equilibrium at point 1 (where IS1 and LM1 intersect) in Home’s IS-LM diagram in panel (a). Home output is at Y1, which is lower than Home’s desired output Y0. Foreign is in equilibrium at point 1′ (where IS1 and LM1 intersect) in Foreign’s IS-LM diagram in panel (b). Because it is the center country, Foreign is assumed to have used stabilization policy and is therefore at its preferred output level  . The Home interest rate equals the Foreign interest rate,

. The Home interest rate equals the Foreign interest rate,  , because Home is pegged to Foreign; this is the interest rate shown on both vertical axes.

, because Home is pegged to Foreign; this is the interest rate shown on both vertical axes.

Because this is a unilateral peg, only Foreign, the center country, has monetary policy autonomy and the freedom to set nominal interest rates. Home is in recession (its output Y1 is below its desired output Y0), but Foreign has its desired output. If Foreign makes no policy concession to help Home out of its recession, this would be the noncooperative outcome. There would be no burden sharing between the two countries: Home is the only country to suffer.

331

Now suppose we shift to a cooperative outcome in which the center country makes a policy concession. How? Suppose Foreign lowers its interest rate from  to

to  . Home can now do the same, and indeed must do so to maintain the peg. How do the IS curves shift? A lower Foreign interest rate implies that, all else equal, Home demand is lower, so the Home IS curve shifts in to IS2; similarly, in panel (b), a lower Home interest rate implies that, all else equal, Foreign demand is lower, so the Foreign IS* curve shifts in to

. Home can now do the same, and indeed must do so to maintain the peg. How do the IS curves shift? A lower Foreign interest rate implies that, all else equal, Home demand is lower, so the Home IS curve shifts in to IS2; similarly, in panel (b), a lower Home interest rate implies that, all else equal, Foreign demand is lower, so the Foreign IS* curve shifts in to  in panel (b). However, the easing of monetary policy in both countries means that the LM curves shift down in both countries to LM2 and

in panel (b). However, the easing of monetary policy in both countries means that the LM curves shift down in both countries to LM2 and  .

.

This is useful to work through both because the result is interesting and because it offers such a complicated figure exercise with the model. Go through it slowly.

What is the net result of all these shifts? To figure out the extent of the shift in the IS curve, we can think back to the Keynesian cross and the elements of demand that underlie points on the IS curve. The peg is being maintained. Because the nominal exchange rate is unchanged, the real exchange rate is unchanged, so neither country sees a shift in its Keynesian cross demand curve due to a change in the trade balance. But both countries do see a rise in the Keynesian cross demand curve, as investment demand rises thanks to lower interest rates. The rise in demand tells us that new equilibrium points 2 and 2′ lie to the right of points 1 and 1′: even though the IS curves have shifted in, the downward shifts in the LM curves dominate, and so output in each country will rise in equilibrium.

332

Compared with the noncooperative equilibrium outcome at points 1 and 1′, Foreign now accepts a rise in output away from its preferred stable level, as output booms from  to

to  . Meanwhile, Home is still in recession, but the recession is not as deep, and output is at a level Y2 that is higher than Y1. In the noncooperative case, Foreign achieves its ideal output level and Home suffers a deep recession. In the cooperative case, Foreign suffers a slightly higher output level than it would like and Home suffers a slightly lower output level than it would like. The burden of the adverse shock to Home has been shared with Foreign.

. Meanwhile, Home is still in recession, but the recession is not as deep, and output is at a level Y2 that is higher than Y1. In the noncooperative case, Foreign achieves its ideal output level and Home suffers a deep recession. In the cooperative case, Foreign suffers a slightly higher output level than it would like and Home suffers a slightly lower output level than it would like. The burden of the adverse shock to Home has been shared with Foreign.

Caveats Why would Home and Foreign agree to a cooperative arrangement in the first place? Cooperation might be possible in principle if neither country wants to suffer too much exchange rate volatility against the other—that is, if they are close to wanting to be in a fixed arrangement but neither wants to unilaterally peg to the other. A unilateral peg by either country gives all the benefits of fixing to both countries but imposes a stability cost on the noncenter country alone. If neither country is willing to pay that price, there can be no unilateral peg by either country. They could simply float, but they would then lose the efficiency gains from fixing. But if they can somehow set up a peg with a system of policy cooperation, then they could achieve a lower instability burden than under a unilateral peg and this benefit could tip the scales enough to allow the gains from fixing to materialize for both countries.

Cooperation sounds great on paper. But the historical record casts doubt on the ability of countries to even get as far as announcing cooperation on fixed rates, let alone actually backing that up with true cooperative behavior. Indeed, it is rare to see credible cooperative announcements under floating rates, where much less is at stake. Why?

A major problem is that, at any given time, the shocks that hit a group of economies are typically asymmetric. A country at its ideal output level not suffering a shock may be unwilling to change its monetary policies just to help out a neighbor suffering a shock and keep a peg going. In theory, cooperation rests on the idea that my shock today could be your shock tomorrow, and we can all do better if we even out the burdens with the understanding that they will “average out” in the long run. But policy makers have to be able to make credible long-run commitments to make this work and suffer short-run pain for long-run gain. History shows that these abilities are often sadly lacking: shortsighted political goals commonly win out over longer-term economic considerations.

For example, consider the European ERM, which was effectively a set of unilateral pegs to the German mark, and now to the euro. The ERM was built around the idea of safeguarding gains from trade in Europe by fixing exchange rates, but the designers knew that it had to incorporate some burden-sharing measures to ensure that the burden of absorbing shocks didn’t fall on every country but Germany. The measures proved inadequate, however, and in the crisis of 1992 the German Bundesbank ignored pleas from Italy, Britain, and other countries for an easing of German monetary policy as recessions took hold in the bloc of countries pegging to the German mark. When the test of cooperation came along, Germany wanted to stabilize Germany’s output, and no one else’s. Thus, even in a group of countries as geographically and politically united as the European Union, it was tremendously difficult to make this kind of cooperation work. (This problem was supposed to be alleviated by true monetary union, with the arrival of the euro and the creation of the European Central Bank in 1999, but even there tensions remain.)

The U.S. at the end of Bretton Woods might be another example to use.

Our main conclusion is that, in practice, the center country in a reserve currency system has tremendous autonomy, which it may be unwilling to give up, thus making cooperative outcomes hard to achieve consistently.

333

Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Exchange Rates

We have studied interest rate cooperation. Is there scope for cooperation in other ways? Yes. Countries may decide to adjust the level of the fixed exchange rate. Such an adjustment is (supposedly) a “one-shot” jump or change in the exchange rate at a particular time, which for now we assume to be unanticipated by investors. Apart from that single jump, at all times before and after the change, the exchange rate is left fixed and Home and Foreign interest rates remain equal.

Suppose a country that was previously pegging at a rate  announces that it will henceforth peg at a different rate,

announces that it will henceforth peg at a different rate,  . By definition, if

. By definition, if  , there is a devaluation of the home currency; if

, there is a devaluation of the home currency; if  , there is a revaluation of the home currency.

, there is a revaluation of the home currency.

These terms are similar to the terms “depreciation” and “appreciation,” which also describe exchange rate changes. Strictly speaking, the terms “devaluation” and “revaluation” should be used only when pegs are being adjusted; “depreciation” and “appreciation” should be used to describe exchange rates that float up or down. Note, however, that these terms are often used loosely and interchangeably.

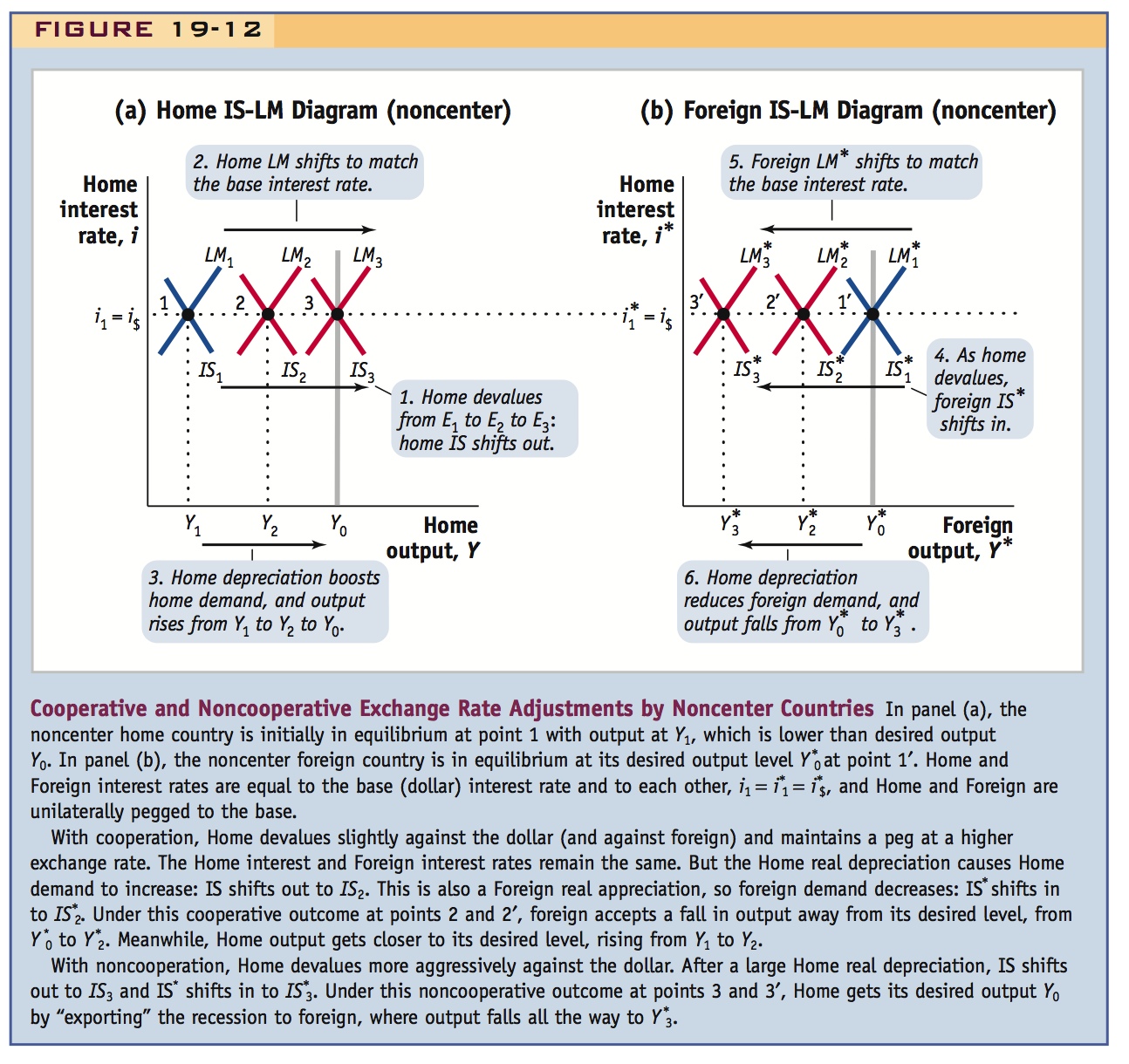

A framework for understanding peg adjustment is shown in Figure 19-12. We assume now that both Home and Foreign are noncenter countries in a pegged exchange rate system and that each is pegged to a third center currency, say, the U.S. dollar.

(Why this change in the setup compared with the last section? Interest rate adjustment required us to study moves by the center country to help noncenter countries; with exchange rate adjustment, noncenter countries change their exchange rates relative to the center, so in this problem our focus shifts away from the center country.)

We assume that the center (the United States) is a large country with monetary policy autonomy that has set its interest rate at i$. Home is pegged to the U.S. dollar at  and Foreign is pegged at

and Foreign is pegged at  . In Home’s IS-LM diagram in panel (a), equilibrium is initially at point 1 (where IS1 and LM1 intersect). Again, because of a prior adverse demand shock, Home output is at Y1 and is lower than Home’s desired output Y0. In Foreign’s IS-LM diagram in panel (b), equilibrium is at Foreign’s desired output level

. In Home’s IS-LM diagram in panel (a), equilibrium is initially at point 1 (where IS1 and LM1 intersect). Again, because of a prior adverse demand shock, Home output is at Y1 and is lower than Home’s desired output Y0. In Foreign’s IS-LM diagram in panel (b), equilibrium is at Foreign’s desired output level  at point 1′ (where

at point 1′ (where  and

and  intersect). Because Home and Foreign peg to the center currency (here, the U.S. dollar), Home and Foreign interest rates equal the dollar interest rate,

intersect). Because Home and Foreign peg to the center currency (here, the U.S. dollar), Home and Foreign interest rates equal the dollar interest rate,  .

.

Now suppose that in a cooperative arrangement, Home devalues against the dollar (and against Foreign) and maintains a peg at a new, higher exchange rate. That is, there is an unanticipated rise in  . The Home and Foreign interest rates remain equal to the dollar interest rate,

. The Home and Foreign interest rates remain equal to the dollar interest rate,  , because both countries still peg. We can think back to the IS-LM model, or back to the Keynesian cross that we used to construct the IS curve, if necessary, to figure out the effect of the change. Because the nominal depreciation by Home is also a real depreciation, Home sees demand increase: the Home IS curve shifts out to IS2. Furthermore, the real depreciation for Home is also a real appreciation for Foreign, so Foreign demand decreases: the IS* curve shifts in to

, because both countries still peg. We can think back to the IS-LM model, or back to the Keynesian cross that we used to construct the IS curve, if necessary, to figure out the effect of the change. Because the nominal depreciation by Home is also a real depreciation, Home sees demand increase: the Home IS curve shifts out to IS2. Furthermore, the real depreciation for Home is also a real appreciation for Foreign, so Foreign demand decreases: the IS* curve shifts in to  . The outcome is cooperative because the burden of the adverse demand shock is being shared: Home output at Y2 is lower than the ideal Y0 but not as low as at Y1; and Foreign has accepted output lower at

. The outcome is cooperative because the burden of the adverse demand shock is being shared: Home output at Y2 is lower than the ideal Y0 but not as low as at Y1; and Foreign has accepted output lower at  than its ideal

than its ideal  .

.

Students will ask why countries would cooperate. Answer that it may be a repeated game, but concede that cooperation may in fact be difficult to enforce (as the historical record seems to suggest).

Why might this kind of cooperation work? Home and Foreign could agree that Home would devalue a little (but not too much) so that both countries would jointly feel the pain. Some other time, when Foreign has a nasty shock, Home would “repay” by feeling some of Foreign’s pain.

334

So devaluations are in fact often beggar-thy-neighbor policies.

Now suppose we shift to a noncooperative outcome in which Home devalues more aggressively against the dollar. After a large real depreciation by Home, Home demand is greatly boosted, and the Home IS curve shifts out all the way to IS3. Home’s real depreciation is also a large real appreciation for Foreign, where demand is greatly reduced, so the Foreign IS* curve shifts in all the way to  . The outcome is noncooperative: Home now gets its preferred outcome with output at its ideal level Y0; it achieves this by “exporting” the recession to Foreign, where output falls all the way to

. The outcome is noncooperative: Home now gets its preferred outcome with output at its ideal level Y0; it achieves this by “exporting” the recession to Foreign, where output falls all the way to  .

.

There are two qualifications to this analysis. First, we have only considered a situation in which Home wishes to devalue to offset a negative demand shock. But the same logic applies when Home’s economy is “overheating” and policy makers fear that output is above the ideal level, perhaps creating a risk of inflationary pressures. In that case, Home may wish to revalue its currency and export the overheating to Foreign.

Second, we have not considered the center country, here the United States. In reality, the center country also suffers some decrease in demand if Home devalues because the center will experience a real appreciation against Home. However, there is less to worry about in this instance: because the United States is the center country, it has policy autonomy, and can always use stabilization policy to boost demand. Thus, there may be a monetary easing in the center country, a secondary effect that we do not consider here.

335

Mention the competitive devaluations of the Great Depression, and their devastating consequences.

Caveats We can now see that adjusting the peg is a policy that may be cooperative or noncooperative in nature. If noncooperative, it is usually called a beggar-thy-neighbor policy: Home can improve its position at the expense of Foreign and without Foreign’s agreement. When Home is in recession, and its policy makers choose a devaluation and real depreciation, they are engineering a diversion of some of world demand toward Home goods and away from the rest of the world’s goods.

This finding brings us to the main drawback of admitting noncooperative adjustments into a fixed exchange rate system. Two can play this game! If Home engages in such a policy, it is possible for Foreign to respond with a devaluation of its own in a tit-for-tat way. If this happens, the pretense of a fixed exchange rate system is over. The countries no longer peg and instead play a new noncooperative game against each other with floating exchange rates.

Cooperation may be most needed to sustain a fixed exchange rate system with adjustable pegs, so as to restrain beggar-thy-neighbor devaluations. But can it work? Consider continental Europe since World War II, under both the Bretton Woods system and the later European systems such as ERM (which predated the euro). A persistent concern of European policy makers in this period was the threat of beggar-thy-neighbor devaluations. For example, the British pound and the Italian lira devalued against the dollar and later the German mark on numerous occasions from the 1960s to the 1990s. Although some of these peg adjustments had the veneer of official multilateral decisions, some (like the 1992 ERM crisis) occurred when cooperation broke down.

The gold standard was a symmetric system with no center currency. All countries pegged to gold, and so were indirectly pegged to each other. It rested upon the principle of convertibility: every central bank was ready to convert its gold for currency and trade in gold was unrestricted. Arbitrage in gold would change money supplies endogenously to stabilize exchange rates. Comments: (1) In practice arbitrage was not costless, so there was a small band—the upper and lower gold points—within which the exchange rate could fluctuate without arbitrage. But the band was very narrow. (2) Since expected depreciation was zero (ignoring fluctuations within the gold points), interest rates had to equalize: the trilemma still applies. (3) The system is symmetric if all countries allow their money supplies to adjust (by gold flows): No country has the privilege of having an independent monetary policy. But it didn’t always work that way.

The Gold Standard

Our analysis in this section has focused on the problems of policy conflict in a reserve currency system in which there is one center country issuing a currency (e.g., the dollar or euro) to which all other noncenter countries peg. As we know from Figure 19-1, this is an apt description of most fixed exchange rate arrangements at the present time and going back as far as World War II. A key issue in such systems is the asymmetry between the center country, which retains monetary autonomy, and the noncenter countries, which forsake it.

Are there symmetric fixed exchange rate systems, in which there is no center country and the asymmetry created by the Nth currency problem can be avoided? In theory the ERM system worked this way before the advent of the euro in 1999, but, as the 1992 crisis showed, there was, in practice, a marked asymmetry between Germany and the other ERM countries. Historically, the only true symmetric systems have been those in which countries fixed the value of their currency relative to some commodity. The most famous and important of these systems was the gold standard, and this system had no center country because countries did not peg the exchange rate at  , the local currency price of some base currency, but instead they pegged at

, the local currency price of some base currency, but instead they pegged at  , the local currency price of gold.

, the local currency price of gold.

336

How did this system work? Under the gold standard, gold and money were seam-lessly interchangeable, and the combined value of gold and money in the hands of the public was the relevant measure of money supply (M). For example, consider two countries, Britain pegging to gold at  (pounds per ounce of gold) and France pegging to gold at

(pounds per ounce of gold) and France pegging to gold at  (francs per ounce of gold). Under this system, one pound cost 1/

(francs per ounce of gold). Under this system, one pound cost 1/ ounces of gold, and each ounce of gold cost

ounces of gold, and each ounce of gold cost  francs, according to the fixed gold prices set by the central banks in each country. Thus, one pound cost

francs, according to the fixed gold prices set by the central banks in each country. Thus, one pound cost  francs, and this ratio defined the par exchange rate implied by the gold prices in each country.

francs, and this ratio defined the par exchange rate implied by the gold prices in each country.

The gold standard rested on the principle of free convertibility. This meant that central banks in both countries stood ready to buy and sell gold in exchange for paper money at these mint prices, and the export and import of gold were unrestricted. This allowed arbitrage forces to stabilize the system. How?

American Numismatic Association

Suppose the market exchange rate in Paris (the price of one pound in francs) was E francs per pound and deviated from the par level, with E < Epar francs per pound. This would create an arbitrage opportunity. The franc has appreciated relative to pounds, and arbitrageurs could change 1 ounce of gold into  francs at the central bank, and then into

francs at the central bank, and then into  pounds in the market, which could be shipped to London and converted into

pounds in the market, which could be shipped to London and converted into  ounces of gold, which could then be brought back to Paris. Because we assumed that

ounces of gold, which could then be brought back to Paris. Because we assumed that  , and the trader ends up with more than an ounce of gold and makes a profit.

, and the trader ends up with more than an ounce of gold and makes a profit.

As a result of this trade, gold would leave Britain and the British money supply would fall (pounds would be redeemed at the Bank of England by the French traders, who would export the gold back to France). As gold entered France, the French money supply would expand (because the traders could leave it in gold form, or freely change it into franc notes at the Banque de France).

We can note how the result tends to stabilize the foreign exchange market (just as interest arbitrage did in the chapters on exchange rates). Here, the pound was depreciated relative to par and the arbitrage mechanism caused the British money supply to contract and the French money supply to expand. The arbitrage mechanism depended on French investors buying “cheap” pounds. This would bid up the price of pounds in Paris, so E would rise toward Epar, stabilizing the exchange rate at its par level.

Four observations are worth noting. First, the process of arbitrage was not really costless, so if the exchange rate deviated only slightly from parity, the profit from arbitrage might be zero or negative (i.e., a loss). Thus, there was a small band around the par rate in which the exchange rate might fluctuate without any arbitrage occurring. However, this band, delineated by limits known as the upper and lower “gold points,” was typically small, permitting perhaps at most ±1% fluctuations in E on either side of Epar. The exchange rate was, therefore, very stable. For example, from 1879 to 1914, when Britain and the United States were pegged to gold at a par rate of $4.86 per pound, the daily dollar–pound market exchange rate in New York was within 1% of its par value 99.97% of the time (and within half a percent 77% of the time).18

Second, in our example we examined arbitrage in only one direction, but, naturally, there would have been a similar profitable arbitrage opportunity—subject to transaction costs—in the opposite direction if E had been above Epar and the franc had been depreciated relative to parity. (Working out how one makes a profit in that case, and what the net effect would be on each country’s money supply, is left as an exercise.)

337

Third, gold arbitrage would enforce a fixed exchange rate at Epar (plus or minus small deviations within the gold points), thus setting expected depreciation to zero. Interest arbitrage between the two countries’ money markets would equalize the interest rates in each country (subject to risk premiums). So our earlier approach to the study of fixed exchange rates remains valid, including a central principle, the trilemma.

Fourth, and most important, we see the inherent symmetry of the gold standard system when operated according to these principles. Both countries share in the adjustment mechanism, with the money supply contracting in the gold outflow country (here, Britain) and the money supply expanding in the gold inflow country (here, France). In theory, if these principles were adhered to, neither country has the privileged position of being able to not change its monetary policy, in marked contrast to a center country in a reserve currency system. But in reality, the gold standard did not always operate quite so smoothly, as we see in the next section.

A numerical example helps here.

Assign this as a homework problem, or invite a team of students to exposit it on the board.

Emphasize the importance of the rules of the game.