4 International Monetary Experience

Apply the tools we have developed to explain actual, historical choices about exchange rate regime.

1. The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard

There was rapid growth in trade from 1870 until 1914. This integration increased the benefit from having a fixed rate. There was little concern about stabilization policies, partly because growth was perceived as stable, and partly because the people most affected by the business cycle had little political power. Price stability was the priority. These considerations also pointed towards fixed rates. Why gold? Using a commodity as the standard confers a network externality, so that only one can dominate in the end. There were problems: Prices and output stagnated in the U.S. in the 1890s, so the Populist Party agitated to leave the gold standard. But the Populists lost, and the U.S. stayed in gold.

WWI forced countries to rely upon seigniorage from inflation, so they gave up the gold standard. Also the volume trade fell during the war, a trend prolonged by protectionist policies in the interwar years. The decrease in integration lowered the benefits of fixed rates. The Great Depression increased the costs of having fixed rates by increasing the need for stabilization policies. Countries engaged in competitive devaluations. This undermined the credibility of the pegs, and prompted speculation that led to currency crises. The gold standard unraveled. In terms of the trilemma, countries responded in three different ways: (1) Some, like the U.S. and Britain, opted to keep capital mobility but adopted flexible rates; (2) others, like Germany, adopted capital controls to regain control of monetary policy, but retained fixed rates; (3) still others, like France and Switzerland, kept both capital mobility and fixed rates. But countries that kept on gold were hit harder and longer by the Depression.

2. Bretton Woods to the Present

The Bretton Woods system reinstated fixed rates—countries pegged to the dollar, which in turn was pegged to gold—but it also embraced capital controls. However, by the late 1950s many countries wanted to liberalize capital flows; furthermore, investors found ways to circumvent capital controls. As capital started to flow more freely, countries started to lose control of their monetary policies. This meant they had to resort to devaluations as a policy instrument, which became more and more frequent. This in turn encouraged speculation, making the system less stable. In the 1960s the U.S. suffered from inflation, which made other countries less willing to peg to the dollar. The U.S. went off gold in 1971, and Bretton Woods collapsed between 1971 and 1973. Various responses: (1) Most advance economies (like the U.S.) adopted capital mobility and flexible rates; (2) others (like the ERM) adopted capital mobility, but tried to keep fixed rates among themselves; (3) some developing countries have kept capital controls, others see the value of capital mobility, but are afraid of floating and still peg; (4) some countries (like India) have tried to find an intermediate regime, such as dirty floats; (5) some countries (like China) have imposed capital controls, although this may be changing, and manage their currencies.

A vast diversity of exchange rate arrangements have been used throughout history. In the chapter that introduced exchange rates, we saw how different countries fix or float at present; at the start of this chapter, we saw how exchange rate arrangements have fluctuated over more than a century. These observations motivated us to study how countries choose to fix or float.

To try to better understand the international monetary experience and how we got to where we are today, we now apply what we have learned in the book so far.19 In particular, we rely on the trilemma, which tells us that countries cannot simultaneously meet the three policy goals of a fixed exchange rate, capital mobility, and monetary policy autonomy. With the feasible policy choices thus set out, we draw on the ideas of this chapter about the costs and benefits of fixed and floating regimes to try to understand why various countries have made the choices they have at different times.

The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard

As we saw in Figure 19-1, the history of international monetary arrangements from 1870 to 1939 was dominated by one story: the rise and fall of the gold standard regime. In 1870 about 15% of countries were on gold, rising to about 70% in 1913 and almost 90% during a brief period of resumption in the 1920s. But by 1939, only about 25% of the world was pegged to gold. What happened? The analysis in this chapter provides insights into one of the grand narratives of economic history.20

The period from 1870 to 1914 was the first era of globalization, with increasingly large flows of trade, capital, and people between countries. Depending on the countries in question, some of these developments were due to technological developments in transport and communications (such as steamships, the telegraph, etc.) and some were a result of policy change (such as tariff reductions). Our model suggests that as the volume of trade and other economic transactions between nations increase, there will be more to gain from adopting a fixed exchange rate (as in Figure 19-4). Thus, as nineteenth-century globalization proceeded, it is likely that more countries crossed the FIX line and met the economic criteria for fixing.

338

Explaining why the gold standard developed when it did here is a very nice application of the basic criteria for fixing.

There were also other forces at work encouraging a switch to the gold peg before 1914. The stabilization costs of pegging were either seen as insignificant—because the pace of economic growth was not that unstable—or else politically irrelevant—because the majority of those adversely affected by business cycles and unemployment were from the mostly disenfranchised working classes. With the exception of some emerging markets, price stability was the major goal and the inflation tax was not seen as useful except in emergencies.

Students find this concept very interesting. Ask them if they can think of other examples (twitter might strike a chord).

As for the question, why peg to gold? (as opposed to silver, or something else), note that once a gold peg became established in a few countries, the benefits of adoption in other countries would increase further. If you are the second country to go on the gold standard, it lowers your trade costs with one other country; if you are the 10th or 20th country to go on, it lowers your trade costs with 10 or 20 other countries; and so on. This can be thought of as a “snowball effect” (or network externality, as economists say), where only one standard can dominate in the end.21

It is fun to digress and talk about the Wizard of Oz as an allegory about the gold standard.

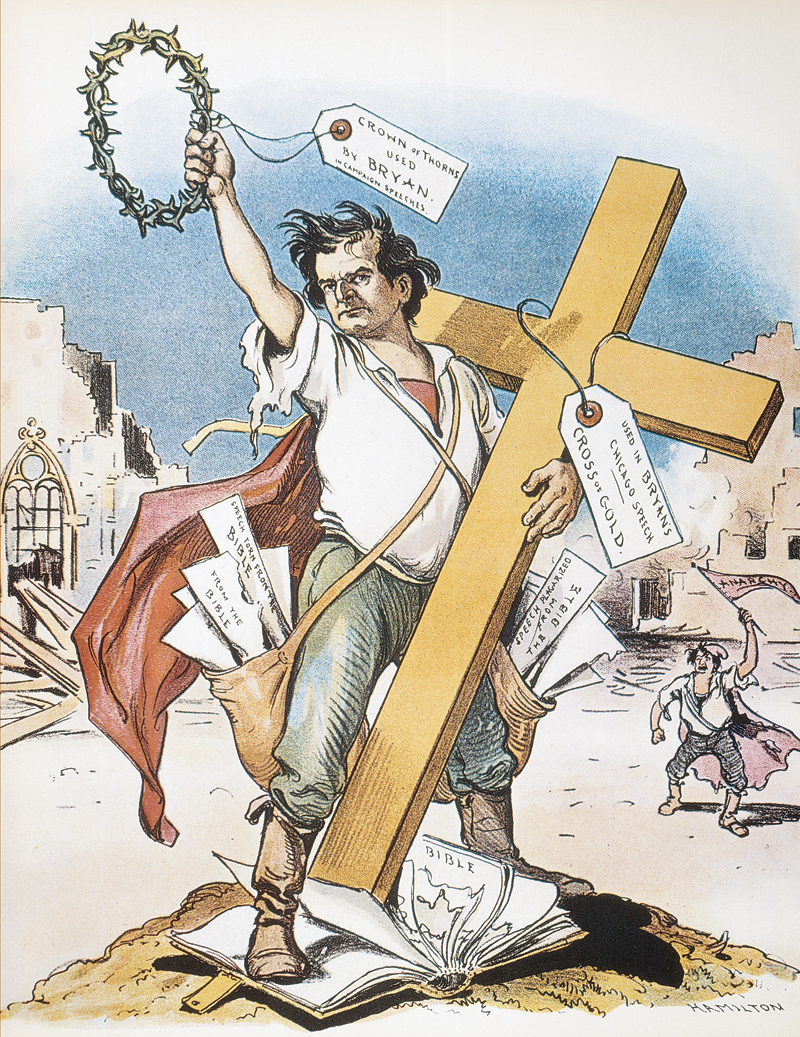

This is not to say that all was plain sailing before 1914. Many countries joined gold, only to leave temporarily because of a crisis. Even in countries that stayed on gold, not everyone loved the gold standard. The benefits were often less noticeable than the costs, particularly in times of deflation or in recessions. For example, in the United States, prices and output stagnated in the 1890s. As a result, many people supported leaving the gold standard to escape its monetary restrictions. The tensions reached a head in 1896 at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, when presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan ended his speech saying: “Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” (Bryan lost, the pro-gold McKinley became president, the Gold Standard Act of 1900 was passed to bury any doubts, and tensions defused as economic growth and gold discoveries raised output and prices.)

Try to find the famous graph by Kindleberger (in the World in Depression) showing the volume of trade spiraling downwards.

These trends were upset by World War I. Countries participating in the war needed some way to finance their efforts. The inflation tax was heavily used, and this implied exit from the gold standard. In addition, once the war began in Europe (and later drew in the United States), the majority of global trade was affected by it: trade was almost 100% wiped out between warring nations, and fell by 50% between participants and neutral countries. This effect persisted long after the war ended, and was made worse by protectionism (higher tariffs and quotas) in the 1920s. By the 1930s, world trade had fallen to close to half of its 1914 level. All of these developments meant less economic integration—which in turn meant that the rationale for fixing based on gains from trade was being weakened.22

339

Then, from 1929 on, the Great Depression undermined the stability argument for pegging to gold. The 1920s and 1930s featured much more violent economic fluctuations than had been seen prior to 1914, raising the costs of pegging. Moreover, politically speaking, these costs could no longer be ignored so easily with the widening of the franchise over time. The rise of labor movements and political parties of the left started to give voice and electoral weight to constituencies that cared much more about the instability costs of a fixed exchange rate.23

Consider depicting how deflation might exacerbate a recession using IS-LM.

Mention that Ben Bernanke did famous research suggesting that countries that abandoned gold recovered faster and were hurt less by the Depression. Students may have heard of him.

Other factors also played a role. The Great Depression was accompanied by severe deflation, so to stay on gold might have risked further deflation given the slow growth of gold supplies to which all money supplies were linked. Deflation linked to inadequate gold supplies therefore undermined the usefulness of gold as a nominal anchor.24 Many countries had followed beggar-thy-neighbor policies in the 1920s, choosing to re-peg their currencies to gold at devalued rates, making further devaluations tempting. Among developing countries, many economies were in recession before 1929 because of poor conditions in commodity markets, so they had another reason to devalue (as some did as early as 1929). The war had also left gold reserves distributed in a highly asymmetric fashion, leaving some countries with few reserves for intervention to support their pegs. As backup, many countries used major currencies as reserves, but the value of these reserves depended on everyone else’s commitment to the gold peg, a commitment that was increasingly questionable.

All of these weaknesses undermined the confidence and credibility of the commitment to gold pegs in many countries, making the collapse of the pegs more likely. Currency traders would then speculate against various currencies, raising the risk of a crisis. In the face of such speculation, in 1931 both Germany and Austria imposed capital controls, and Britain floated the pound against gold. The gold standard system then unraveled in a largely uncoordinated, uncooperative, and destructive fashion.

Notice how the text weaves the theory into a narrative of historical changes. Try to do this in class. It will deepen understanding of the theory and convince students of its usefulness.

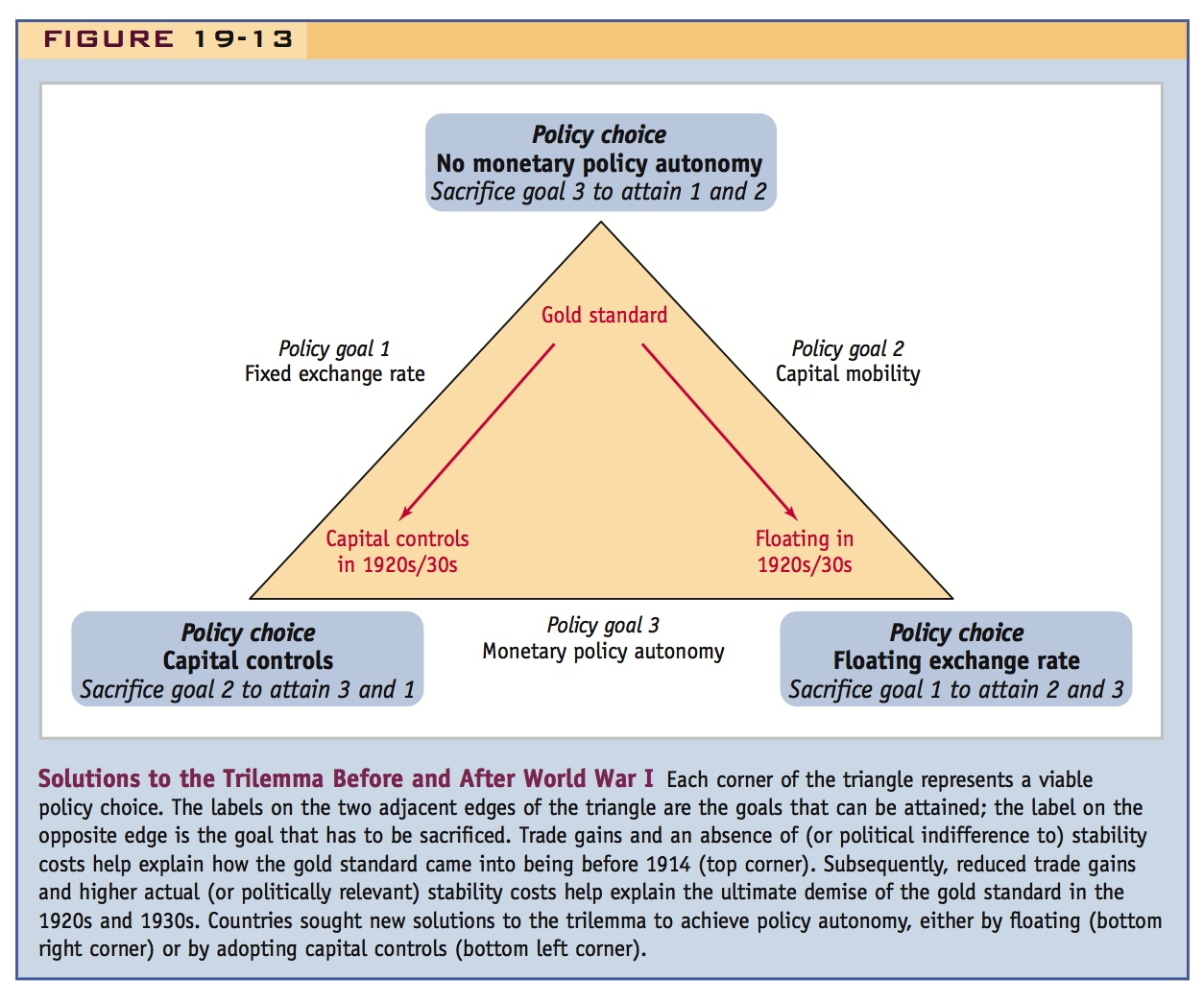

In the language of the trilemma, with its three solutions or “corners,” the 1930s saw a movement by policy makers away from the “open capital market/fixed exchange rate” corner, and the other two corners came to dominate. Countries unwilling to close their capital markets by imposing controls opted to abandon the gold peg and moved to the open capital market/floating exchange rate solution, allowing them to regain monetary policy autonomy: Britain and the United States among others made this choice. Countries willing to adopt capital controls but unwilling to suffer the volatility of a floating rate moved to the “closed capital market/fixed exchange rate” solution, allowing them to regain monetary policy autonomy in a different way: Germany and many countries in South America made this choice. Gaining monetary autonomy gave all of these countries the freedom to pursue more expansionary monetary policies to try to revive their economies, and most of them did just that. Finally, a few countries (such as France and Switzerland) remained on the gold standard and did not devalue or impose controls, because they were not forced off gold (they had large reserves) and because they were worried about the inflationary consequences of floating. Countries that stuck with the gold standard paid a heavy price: compared with 1929, countries that floated had 26% higher output in 1935, and countries that adopted capital controls had 21% higher output, as compared with the countries that stayed on gold.25

340

Figure 19-13 shows these outcomes. To sum up: although many other factors were important, trade gains and an absence of (or political indifference to) stability costs helped bring the gold standard into being before 1914; reduced trade gains and stability costs that were higher (or more politically relevant) help explain the ultimate demise of the gold standard in the interwar period.

Bretton Woods to the Present

The international monetary system of the 1930s was chaotic. Near the end of World War II, allied economic policy makers gathered in the United States, at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to try to ensure that the postwar economy fared better. The architects of the postwar order, notably Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, constructed a system that preserved one key tenet of the gold standard regime—by keeping fixed rates—but discarded the other by imposing capital controls. The trilemma was resolved in favor of exchange rate stability to encourage the rebuilding of trade in the postwar period. Countries would peg to the U.S. dollar; this made the U.S. dollar the center currency and the United States the center country. The U.S. dollar was, in turn, pegged to gold at a fixed price, a last vestige of the gold standard.

341

Another nice example of using the theory to elucidate the history.

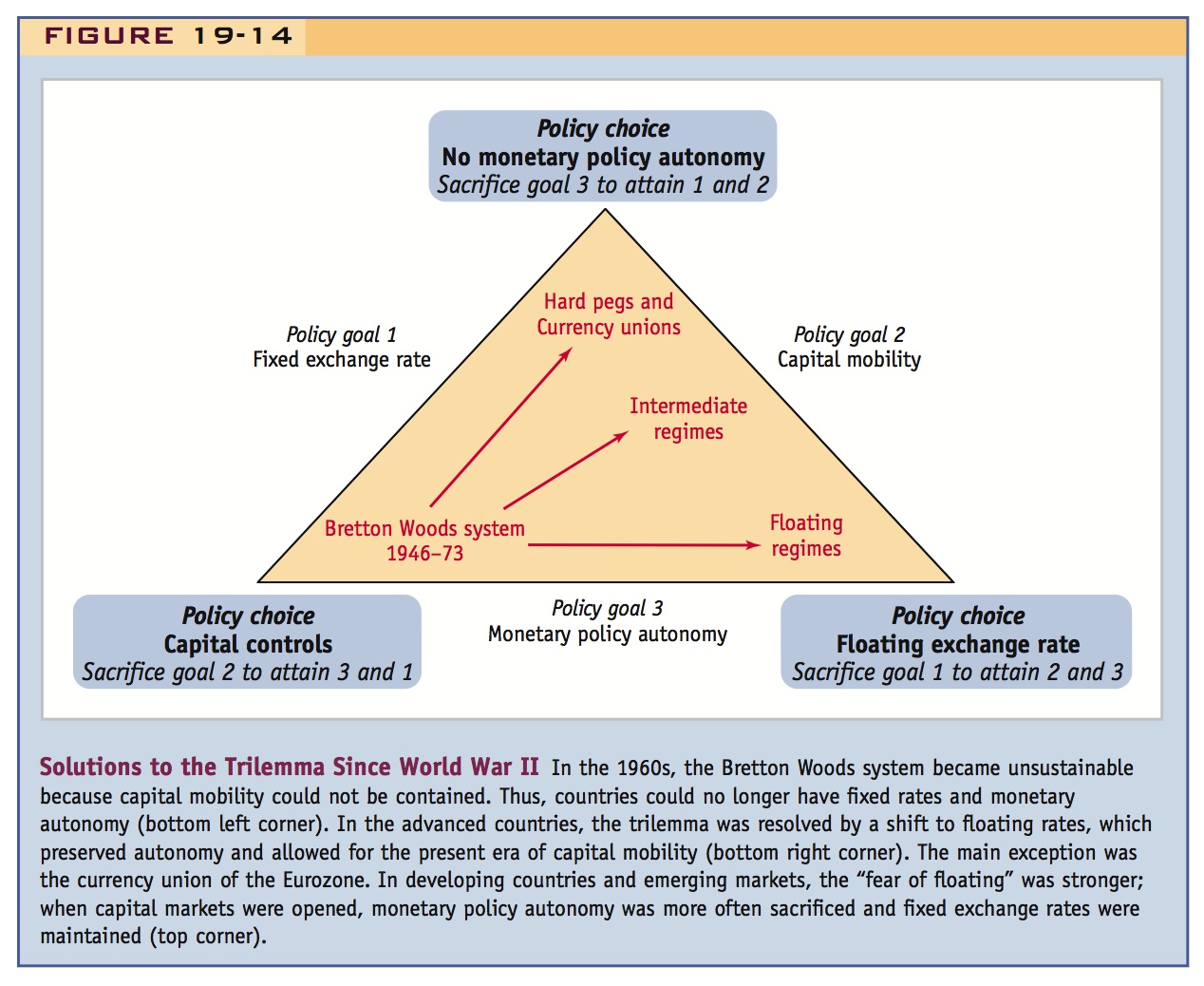

In Figure 19-14, the postwar period starts with the world firmly in the “closed capital market/fixed exchange rate” corner on the left. At Bretton Woods, the interests of international finance were seemingly dismissed, amid disdain for the speculators who had destabilized the gold standard in the 1920s and 1930s: U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau pronounced that the new institutions would “drive…the usurious money lenders from the temple of international finance.” At the time, only the United States allowed full freedom of international capital movement, but this was soon to change.

It was obvious that to have trade one needed to have payments, so some kind of system for credit was needed, at least on a short-term basis. By the late 1950s, after getting by with half measures, many countries in Europe and elsewhere were ready to liberalize financial transactions related to current account transactions to free up the trade and payments system. At the same time, they sought to limit speculative financial transactions that were purely asset trades within the financial account (e.g., interest arbitrage by forex traders).

342

Unfortunately, in practice it proved difficult then (and has proved so ever since) to put watertight controls on financial transactions. Controls in the 1960s were very leaky and investors found ways to circumvent them and move money offshore from local currency deposits into foreign currency deposits. Some used accounting tricks such as over- or underinvoicing trade transactions to move money from one currency to another. Others took advantage of the largely unregulated offshore currency markets that had emerged in London and elsewhere in the late 1950s.

Here too.

As capital mobility grew and controls failed to hold, the trilemma tells us that countries pegged to the dollar stood to lose their monetary policy autonomy. This was already a reason for them to think about exiting the dollar peg. With autonomy evaporating, the devaluation option came to be seen as the most important way of achieving policy compromise in a “fixed but adjustable” system. But increasingly frequent devaluations (and some revaluations) undermined the notion of a truly fixed rate system, made it more unstable, generated beggar-thy-neighbor policies, and—if anticipated—encouraged speculators.

Note that the dollar peg was not supported by the U.S. depleting its international reserves, but by other countries buying up dollars. This meant the U.S. was effectively exporting its inflation.

The downsides became more and more apparent as the 1960s went on. Other factors included a growing unwillingness in many countries to peg to the U.S. dollar, after inflation in the Vietnam War era undermined the dollar’s previously strong claim to be the best nominal anchor currency. It was also believed that this inflation would eventually conflict with the goal of fixing the dollar price of gold and that the United States would eventually abandon its commitment to convert dollars into gold, which happened in August 1971. By then it had become clear that U.S. policy was geared to U.S. interests, and if the rest of the world needed a reminder about asymmetry, they got it from U.S. Treasury Secretary John Connally, who in 1971 uttered the memorable words, “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”

Figure 19-14 tells us what must happen in an international monetary system once capital mobility reasserts itself, as happened to the Bretton Woods system in the 1960s. The “closed capital market/fixed exchange rate” corner on the left is no longer an option. Countries must make a choice: they can stay fixed and have no monetary autonomy (move to the top corner), or they can float and recover monetary autonomy (move to the right corner).

These choices came to the fore after the Bretton Woods system collapsed between 1971 and 1973. How did the world react? There have been a variety of outcomes, and the tools developed in this chapter help us to understand them:

- Most advanced countries have opted to float and preserve monetary policy autonomy. This group includes the United States, Japan, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. They account for the growing share of floating regimes in Figure 19-1. For these countries, stability costs outweigh integration benefits. They are at the bottom right corner of the trilemma diagram.

- A group of European countries instead decided to try to preserve a fixed exchange rate system among themselves, first via the ERM and now “irrevocably” through the adoption of a common currency, the euro. Integration gains in the closely integrated European market might, in part, explain this choice. This group of countries is at the top corner of the trilemma diagram.

- Some developing countries have maintained capital controls, but many of them (especially the emerging markets) have opened their capital markets. Given the “fear of floating” phenomenon, their desire to choose fixed rates (and sacrifice monetary autonomy) is much stronger than in the advanced countries, all else equal. These countries are also at the top corner of the trilemma diagram.

- Some countries, both developed and developing, have camped in the middle ground: they have attempted to maintain intermediate regimes, such as “dirty floats” or pegs with “limited flexibility.” India is often considered to be a case of an intermediate regime somewhere between floating or fixed. Such countries are somewhere in the middle on the right side of the trilemma diagram.

- Finally, some countries still impose some capital controls rather than embrace globalization. China has been in this position, although things are gradually starting to change and the authorities have suggested further moves toward financial liberalization in the future. These countries, mostly developing countries, are clinging to the bottom left corner of the trilemma diagram.