Chapter Introduction

401

The Euro

This chapter is consecrated to the euro. It begins by developing the theory of optimal currency areas, but concludes that the Eurozone is not an optimal currency area. The chapter then puts the euro in its broader historical and political context, and describes its evolution.

- The Economics of the Euro

- The History and Politics of the Euro

- Eurozone Tensions in Tranquil Times, 1999–2007

- The Eurozone in Crisis, 2008–2013

- Conclusions: Assessing the Euro

There is no future for the people of Europe other than in union.

Jean Monnet, a “founding father” of the European Union

This Treaty marks a new stage in the process of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen.

Maastricht Treaty (Treaty on European Union), 1992, Title 1, Article A

Political unity can pave the way for monetary unity. Monetary unity imposed under unfavorable conditions will prove a barrier to the achievement of political unity.

Milton Friedman, Nobel laureate, 1997

Mention that this is the same guy whom we encountered in the IS-LM-FX model.

1. Mundell wondered in 1961 if his famous paper on optimum currency areas had any policy relevance. Forty years later the Eurozone was created and he was awarded the Nobel Prize.

2. This chapter will explore the economics and politics of the euro. Most economists think that, from a purely economic perspective, does not make much sense. From a broader political and social perspective, however, it is part of a bigger undertaking.

3. The Ins and Outs of the Eurozone

Some basic facts: the euro is the currency of the European Union, an economic and increasingly political union of European states. The plan for the euro was laid out in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which created the European Monetary Union (EMU). The EMU was to establish a monetary union with a common monetary policy run by a European Central Bank (ECB). In 2014 there were 28 members of the EU; three countries—Denmark, Sweden, and the UK—are in the EU, but not in the Eurozone. To join the Eurozone a country must first peg to the euro by joining the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM).

In 1961, the economist Robert Mundell wrote a paper discussing the idea of a currency area, also known as a currency union or monetary union, in which states or nations replace their national monies with a single, common currency.

At the time, almost every country was a separate currency area, so Mundell wondered whether his research would have any practical relevance: “What is the appropriate domain of a currency area? It might seem at first that the question is purely academic since it hardly appears within the realm of political feasibility that national currencies would ever be abandoned in favor of any other arrangement.”1

Almost 40 years later, on January 1, 1999, 11 nations in Europe joined together to form such a currency area, now known as the Euro area, or Eurozone. Later that year, Mundell found himself the recipient of a Nobel Prize.

The Eurozone has since expanded and continues to expand. By January 1, 2014, it comprised 18 of the 28 member states of the European Union. They use the notes and coins bearing the name euro and the symbol € that have taken the place of former national currencies (francs, marks, liras, and others).

402

The euro remains one of the boldest experiments in the history of the international monetary system. It is a new currency that is used by more than 330 million people in one of the world’s most prosperous economic regions. The euro is having enormous economic impacts that will be felt for many years to come.

The goal of this chapter is to understand as fully as possible the euro project: its economic as well as political logic, its institutional form and how it actually operates. We first examine the euro’s economic logic by exploring and applying theories that seek to explain when it makes economic sense for different economic units (nations, regions, states) to adopt a common currency and when it makes economic sense for them to have distinct monies. To spoil the surprise: based on the current evidence, most economists judge that the Eurozone may not make sense from a purely economic standpoint, at least for now.

We then turn to the historical and political logic of the euro and discuss its distant origins and recent evolution within the larger political project of the European Union. Looking at the euro from these perspectives, we can see how the euro project unfolded as part of a larger enterprise. In this context, the success of the euro depends on assumptions that the European Union functions smoothly as a political union and adequately as an economic union—assumptions that are constantly under question.

Summarize these broad facts. Many U.S. students may not be familiar them.

The Ins and Outs of the Eurozone Before we begin our discussion of the euro, we need to familiarize ourselves with the EU and the Eurozone. Way back at the start of the euro project policy makers imagined that the euro would end up as the currency of the European Union (EU). The EU is a mainly economic, but increasingly political, union of countries that is in the process of extending across—and some might argue beyond—the geographical boundaries of Europe. The main impetus for the euro project came in 1992 with the signing of the Treaty on European Union, at Maastricht, in the Netherlands. Under the Maastricht Treaty, the EU initiated a grand project of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). A major goal of EMU was the establishment of a currency union in the EU whose monetary affairs would be managed cooperatively by members through a new European Central Bank (ECB).2

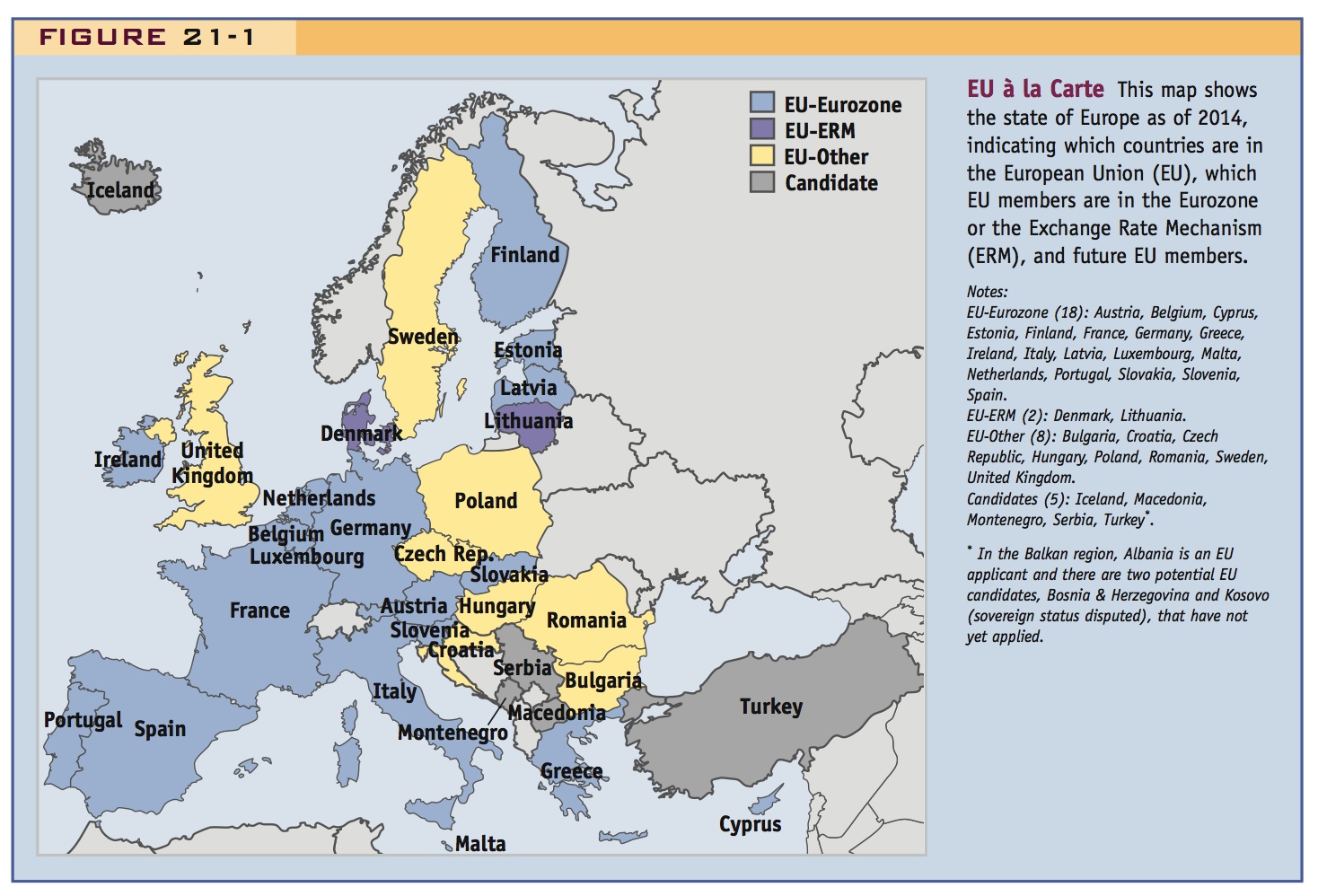

The map in Figure 21-1 shows the state of play at the time of this writing in late 2013. The map depicts some of the EU’s main political and monetary alignments. The two are not the same: different countries choose to participate in different aspects of economic and monetary integration, a curious feature of the EU project known as variable geometry.

- As of 2014, the EU comprised 28 countries (EU-28). Ten of these had joined as of 2004, Romania and Bulgaria joined in 2007, and Croatia in mid-2013. Five more official candidate countries were formally seeking to join—Iceland, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey.3

- A country can be in the EU but not in the Eurozone. It is important to remember who’s “in” and who’s “out.” In 1999, just 3 of 15 EU members opted to stay out of the Eurozone and keep their national currencies: these “out” countries were Denmark, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The other 12 all went “in” by 2001. From then until 2013, a total of 13 new entrants joined the EU, with all of them initially “out” of the euro. Then, on January 1, 2007, the first of these countries, Slovenia, became a member of the Eurozone, followed by Cyprus and Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009), Estonia (2011), and Latvia (2014). As of 2014, the other 7 new entrants still remained “out” of the Eurozone.

- Most of the “outs” want to be “in.” The official procedure to join the Eurozone requires that those who wish to get “in” must first peg their exchange rates to the euro in a system known as the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) for at least two years and must also satisfy certain other qualification criteria. Two countries were part of the ERM as of 2014: Denmark and Lithuania. Participation in the ERM is usually taken as an indication of the intent to adopt the euro shortly (Latvia left the ERM to join the euro in January 2014). We discuss the ERM, the qualification criteria, and other peculiar rules later in this chapter.

404