3 Eurozone Tensions in Tranquil Times, 1999–2007

The Eurozone was a success over this period, with financial stability, no inflation problems, and no recessions. This section talks about how the ECB’s policy rules were developed, and concerns over fiscal stability.

1. The European Central Bank

Key attributes of the ECB: (1) It’s policy instrument is the bank borrowing rate; its goals are first price stability, and second, supporting the economic objectives of the EU. (2) It is forbidden to finance member countries’ deficits or to bail out governments or national public bodies. (3) Monetary policy is set by the Governing Council, which has six members from the ECB’s executive board and the governors of the members’ central banks. (4) It has sole control of monetary policy, and is independent of any political body or state.

a. Criticisms of the ECB

All four points are contentious: (1) Some say price stability is vague and asymmetric (no lower bound); others say there should also be a growth or unemployment target. The ECB is also criticized for using a money target, in addition to an interest rate target, but normally it ignores the money target. (2) The restriction on lending would preclude the extension of credit to troubled banks in a crisis. (3) The deliberations of the Governing Board are criticized as insufficiently transparent. (4) The ECBs lack of accountability may hinder its legitimacy.

b. The German Model

Supporters of the ECB assert that its independence is necessary to prevent political interference and to maintain credibility in fighting inflation. This independence is modeled on the Bundesbank, which was insulated from political pressures, so that it could focus on price stability.

c. Monetary Union with Inflation Bias

Central banks face a time inconsistency problem: A central point may commit to price stability, but unless it can credibly pre-commit to it, it will be tempted to inflate in order to raise output. But if people know the central bank will be tempted to inflate, they will change their expectations and there will be an effect on output. The economy will have an inflationary bias. The German model is a re-commitment device designed to solve the time inconsistency problem. Germany had great bargaining power in designing the ECB, so other countries had to accept the German model.

2. The Rules of the Club

Maastricht set rules for admission to the Eurozone, five convergence criteria:

a. Nominal Convergence

A country must stay within its ERM band for two years. It must have inflation close to that of the lowest inflation countries in the zone. It must have a long-term interest rate close to those in the lowest inflation countries. But adopting the euro would force countries to have the same inflation and interest rates after the fact anyway, so why impose them ahead of time? The answer is that these criteria force countries to converge on a common, low inflation rate. Countries have to prove their commitment to low inflation before joining the club.

b. Fiscal Discipline

Inflation is often caused by fiscal deficits, so Maastricht constrained fiscal policy: debts and deficits cannot exceed prescribed levels as fractions of GDP. This is designed to prevent high-debt countries from lobbying for higher inflation.

c. Criticism of the Convergence Criteria

Criticisms: (1) To converge to inflation rates acceptable to Germany, some countries had to impose tighter monetary and fiscal policies. But austerity policies are especially contractionary under fixed rates. This makes them politically unpalatable, and undermines the credibility of the peg. (2) Since countries abandon monetary policy, they should have some leeway to use fiscal policy as a stabilization tool. (3) Just because a country meets the targets before joining doesn’t mean they will after joining.

3. Sticking to the Rules

How to assure that countries wouldn’t run big deficits and lobby for inflation after joining? Price stability was supposed to be assured by the ECB’s independence. Prudent fiscal policies were supposed to be assured by mechanisms to enforce the Maastricht criteria. This did not work well.

a. The Stability and Growth Pact

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) of 1997 gave the EU greater power to monitor and enforce fiscal discipline. But it was a failure: (1) Some members concealed their budgetary problems (Greece being the most infamous example). (2) Punishment was inadequate. (3) Deficit rules preclude not only stabilization policy, but also automatic stabilizers, making recessions even more painful. (4) The main reason to obey the rules of the club was to get in; after getting in there was little to use as an incentive. The SGP was in ruins by the early 2000s.

From its launch in 1999 until 2007 or so, the Eurozone was considered a success. Compared to what came next, this was a time of economic growth and stability for the Eurozone—a period with no recession and with the ECB untroubled by problems either with its explicit inflation target goal or its broader responsibility to support Eurozone economic and financial stability.

424

In this section we review this fortunate period, focusing on the way in which the ECB’s monetary policy rules were devised, and the broader concerns about fiscal stability. This period will be remembered for a somewhat narrow and limited policy focus and a general complacency concerning some of the ultimately more dangerous macroeconomic trends that we discuss in the section which follows.

The European Central Bank

Suppose some German economists from the 1950s or 1960s, after having traveled forward in time to the present day, pop up next to you on a Frankfurt street corner, and say, “Take me to the central bank.” They are surprised when you lead them to the gleaming glass and steel Eurotower at Kaiserstrasse instead of the old Bundesbank building.

It is no coincidence that the European Central Bank is located in Frankfurt. It is a testament to the strong influence of German monetary policy makers and politicians in the design of the euro project, an influence they earned on account of the exemplary performance of the German economy, and especially its monetary policy, from the 1950s to the 1990s. To see how German influence has left its mark on the euro, we first examine how the ECB operates and then try to explain its peculiar goals and governance.

Go carefully through these features of the ECB, in particular the "primary directive" of price stability and its autonomy. Relate these features to the need for a credible nominal anchor and to the crucial role of Germany in establishing them.

For economists, central banks have a few key features. To sum these up, we may ask: What policy instrument does the bank use? What is it supposed to do (goals) and not do (forbidden activities)? How are decisions on these policies made given the bank’s governance structure? To whom is the bank accountable, and, subject to that, how much independence does the bank have? For the ECB, the brief answers are as follows:

- Instrument and goals. The instrument used by the ECB is the interest rate at which banks can borrow funds. According to its charter, the ECB’s primary objective is to “maintain price stability” in the euro area. Its secondary goal is to “support the general economic policies in the Community with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Community.” (Many central banks have similar instruments and goals, but the ECB has a relatively strong focus on inflation.)

- Forbidden activities. To prevent the use of monetary policy for other goals, the ECB may not directly finance member states’ fiscal deficits or provide bailouts to member governments or national public bodies. In addition, the ECB has no mandate to act as a lender of last resort by extending credit to financial institutions in the Eurozone in the event of a banking crisis. (Most central banks are not so constrained, and they typically can act as a lender of last resort.)

- Governance and decision making. Monetary policy decisions are made at meetings of the ECB’s Governing Council, which consists of the central bank governors of the Eurozone national central banks and six members of the ECB’s executive board. In practice, policy decisions are made by consensus rather than by majority voting. Meetings are usually held twice each month.

- Accountability and independence. No monetary policy powers are given to any other EU institution. No EU institution has any formal oversight of the ECB, and the ECB does not have to report to any political body, elected or otherwise. The ECB does not release the minutes of its meetings. The ECB has independence not only with respect to its instrument (it sets interest rates) but also with respect to its goal (it gets to define what “price stability” means). (A small but growing number of central banks around the world has achieved some independence, but the ECB has more than most.)

On all four points, the working of the ECB has been subject to strong criticisms.

425

Criticisms of the ECB There is controversy over the price stability goal. The ECB chooses to define price stability as a Eurozone consumer price inflation rate of less than but “close to” 2% per year over the medium term. This target is vague (the notions of “close to” and “medium term” are not defined). The target is also asymmetrical (there is no lower bound to guard against deflation), a characteristic that became a particular worry as inflation rates fell toward zero during the Great Recession following the global financial crisis of 2008.

This is a useful comparison to draw with the Fed.

There is controversy over having only price stability as a goal. On paper, the ECB technically has a secondary goal of supporting and stabilizing the Eurozone economy. But in practice, the ECB has acted as if it places little weight on economic performance, growth, and unemployment, and where the real economy is in the business cycle. In this area, the ECB’s policy preferences are different from, say, those of the U.S. Federal Reserve, which has a mandate from Congress not only to ensure price stability but also to achieve full employment. The ECB also differs from the Bank of England, whose former Governor Mervyn King once famously used the term “inflation nutter” to describe a policy maker with an excessive focus on price stability. The ECB’s early obsessive focus on money and prices was thought to reflect a combination of its Germanic heritage and its relative lack of long-term reputation.

There is controversy over the ECB’s way of conducting policy to achieve its goal. In addition to the “first pillar,” which uses an economic analysis of expected price inflation to guide interest rate decisions, the bank has a “second pillar” in the form of a reference value for money supply growth (4.5% per annum). As we saw in the chapter on exchange rates in the long run, however, a fixed money growth rate can be consistent with an inflation target only by chance. For example, in the quantity theory model, which assumes a stable level of nominal interest rates in the long run, inflation equals the money growth rate minus the growth rate of real output. So the ECB’s twin pillars will make sense only if real output just happens to grow at less than 2.5% per year, for only then will inflation be, at most, 4.5 − 2.5 = 2% per year. Perhaps aware of the inconsistency of using two nominal anchors, the ECB has given the impression that most of the time it ignores the second pillar; nonetheless, concern about money supply growth is occasionally expressed.

A timely question that may provoke discussion

There is controversy over the strict interpretation of the “forbidden activities” rules. What happens in the event of a large banking crisis in the Eurozone? When banking crises hit other nations, many central banks would choose to extend credit to specific troubled banks or to relax lending standards to the banking sector as a whole, and they could print money to do so. In the Eurozone, officially the ECB can print the money but it cannot implement either type of additional lending; the national central banks of countries in the Eurozone can do the lending but can’t print the money. National central banks can devise limited, local credit facilities or arrange private consortia to manage a small crisis, or they can hope for fiscal help from their national treasuries. Big crises could therefore prove more difficult to prevent or contain. (In a discussion that appears later in the chapter, we look at how the ECB reacted during and after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and eased these rules somewhat.)

426

There is controversy over the decision-making process and lack of transparency. Votes are not formally required, and no votes of any kind are reported. Consensus decisions are preferred but these may favor the status quo, causing policy to lag when it ought to move. Minutes are recorded but can be kept secret for 30 years and their level of detail is not known. Some parts of meetings are private without any record being kept at all. Insistence on having all central bank governors on the Council leads to a very large body where consensus may be more difficult to achieve. This design will become even more cumbersome as more countries join the euro, but the structure of the Council is set in the Maastricht Treaty and would be impossible to change without revising the treaty.

There is controversy over the ECB’s lack of accountability. Because so much of its operation is secret and it answers to no political masters, some fear that people in the Eurozone will conclude that the ECB lacks legitimacy. Although the EU is a collection of democratic states, many of its decisions are made in places that are far from the people in these states. Many EU bodies suffer a perceived “democratic deficit,” including the work of the unelected Commission and the treaties pursued at the intragovernmental level with no popular ratification and little consultation. The ECB can appear to be even further removed at a supra-governmental level. There is nothing akin to the U.S. requirement that the Federal Reserve chairman regularly answer questions from Congress. Rather, the ECB has a more informal dialogue and consultations with the Council, Commission, and Parliament. In response, the finance ministers of the Eurozone have ganged up to form the Eurogroup, which meets and opines about what is happening in the Eurozone and what the ECB is (or should be) doing. Occasionally, national heads of governments weigh in to attack the ECB’s policy choices or to defend them. Along with the EU’s commissioner for economic and monetary affairs, heads of government can make pronouncements and lobby, but they can do little more unless a treaty revision places the ECB under more scrutiny.

Again emphasize the German influence in the constitution of the euro. Explain the German historical aversion to inflation.

The German Model Some of these criticisms are valid and undisputed, but others are fiercely contested. Supporters of the ECB say that strong independence and freedom from political interference are exactly what is needed in a young institution that is struggling to achieve credibility and that the dominant problem in the Eurozone in the recent past has been inflation not deflation. For many of these supporters, the ECB is set up the right way—almost a copy of the Bundesbank, with a strong focus on low inflation to the exclusion of other criteria and a complete separation of monetary policy from politics. Here, German preferences and German economic performance had been very different from those for the rest of the Eurozone, yet they prevailed. How can this be understood?

German preferences for a low-inflation environment have been extremely strong ever since the costly and chaotic interwar hyperinflation (discussed in the chapter on exchange rates in the long run). It was clear that the hyperinflation had been driven by reckless fiscal policy, which had led politicians to take over monetary policy and run the printing presses. After that fiasco, strong anti-inflation preferences, translated from the people via the political process, were reflected in the conduct of monetary policy by the Bundesbank from 1958 until the arrival of the euro in 1999. To ensure that the Bundesbank could deliver a firm nominal anchor, it was carefully insulated from political interference.

427

Today, as we learned when studying exchange rates in the long run, a popular recipe for sound monetary policy is a combination of central bank independence and an inflation target. Sometimes, the inflation target is set by the government, the so-called New Zealand model. But the so-called German model went further and faster: the Bundesbank was not only the first central bank to be granted full independence, it was also given both instrument independence (freedom to use interest rate policy in the short run) and goal independence (the power to decide what the inflation target should be in the long run). This became the model for the ECB, when Germany set most of the conditions for entering a monetary union with other countries where the traditions of central bank independence were weaker or nonexistent.

This would be a good place to digress and talk about time inconsistency in general (for example, go through the examples at the beginning of the original Kydland & Prescott paper). Also, some students may need more explanation for why anticipated money growth would lead to inflation but have no real effects. In other words, be prepared to develop the intuition of the Barro-Gordon story, without getting lost in the details.

Monetary Union with Inflation Bias We can see where Germany’s preferences came from. But how did it get its way? A deep problem in modern macroeconomics concerns the time inconsistency of policies.12 According to this view, all countries have a problem with inflation bias under discretionary monetary policy. Policy makers would like to commit to low inflation, but without a credible commitment to low inflation, a politically controlled central bank has the temptation to use “surprise” monetary policy expansions to boost output. Eventually, this bias will be anticipated, built into inflation expectations, and hence, in the long run, real outcomes—such as output and unemployment—will be the same whatever the extent of the inflation bias. Long-run money neutrality means that printing money can’t make an economy more productive or create jobs.

Emphasize the importance of an independent central with a price-stability mandate as a commitment device.

The inflation bias problem can be solved if we can separate the central bank from politics and install a “conservative central banker” who cares about inflation and nothing else. This separation was strong in Germany, but not elsewhere. Hence, a historically low-inflation country (e.g., Germany) might be worried that a monetary union with a high-inflation country (e.g., Italy) would lead to a monetary union with on average a tendency for middling levels of inflation—that is, looser monetary policies on average for Germany and tighter on average for Italy. In the long run, Germany and Italy would still get the same real outcomes (though in the short run, Germany might have a monetary-led boom and Italy a recession). But, while Italy might gain in the long run from lower inflation, Germany would lose from the shift to a high-inflation environment. Germany would need assurances that this would not happen, and because Germany was such a large and pivotal country in the EU, a Eurozone without Germany was unimaginable (based on simple OCA logic or on political logic). So Germany had a lot of bargaining power.

Essentially, the bargaining over the design of the ECB and the Eurozone boiled down to this: other countries were content to accept that in the long run their real outcomes would not be any different even if they switched to a monetary policy run by the ECB under the German model, and thus had to settle for less political manipulation of monetary policy.

An interesting interpretation of Maastricht in terms of time inconsistency.

Or so they said at the time. But how could one be sure that these countries did in fact mean what they said? One could take countries’ word for it—trust them. Or one could make them prove it—test them. In a world of inflation bias, trust in monetary authorities is weak, so the Maastricht Treaty established some tests—that is, some rules for admission.

428

The Rules of the Club

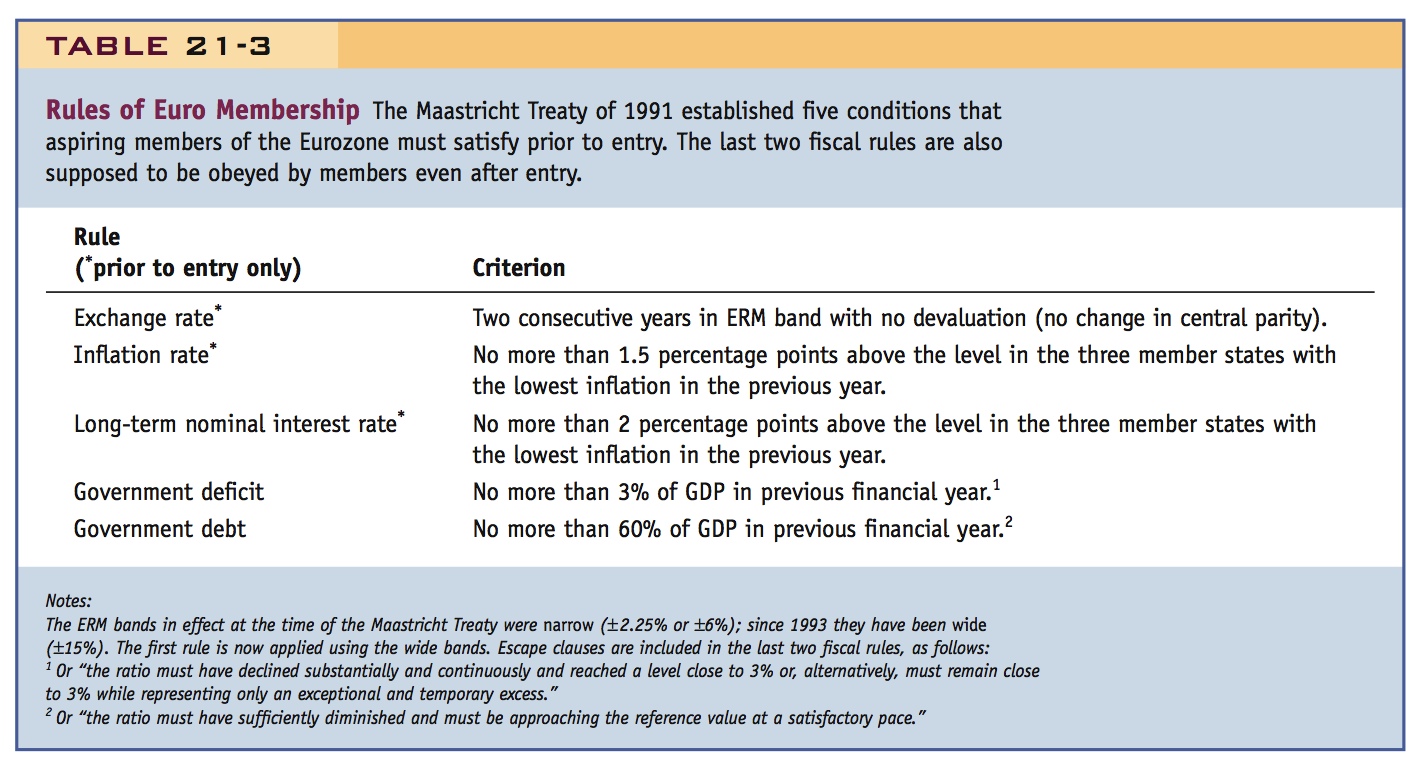

The Maastricht Treaty established five rules for admission to the euro zone, as shown in Table 21-3. All five of these convergence criteria need to be satisfied for entry. Two of the five rules also serve as ongoing requirements for membership. The rules can be divided into two parts: three rules requiring convergence in nominal measures closely related to inflation and two rules requiring fiscal discipline to clamp down on the deeper determinants of inflation.

Nominal Convergence In the chapters on short- and long-run exchange rates, we explored some of the central implications of a fixed exchange rate, implications that also apply when two countries adopt a common currency (i.e., a fixed exchange rate of 1). Let’s consider three implications:

- Under a peg, the exchange rate must be fixed or not vary beyond tight limits.

- Purchasing power parity (PPP) then implies that the two countries’ inflation rates must be very close.

- Uncovered interest parity (UIP) then implies that the two countries’ long-term nominal interest rates must be very close.

In fact, we may recall that the Fisher effect says that the inflation differential must equal the nominal interest rate differential—so if one is small, the other has to be small, too.

These three conditions all relate to the nominal anchoring provided by a peg, and they roughly correspond to the first three Maastricht criteria in Table 21-3.

429

The rules say that a country must stay in its ERM band (with no realignment) for two years to satisfy the peg rule.13 It must have an inflation rate “close to” that of the three lowest-inflation countries in the zone to satisfy the inflation rule. And it must have a long-term interest rate “close to” that in the three low-inflation countries.14 All three tests must be met for a country to satisfy the admission criteria.

What is the economic sense for these rules? They appear, in some ways, superfluous because if a country credibly pegged to (or has adopted) the euro, theory says that these conditions would have to be satisfied in the long run anyway. For that reason they are also difficult to criticize—except to say that, if the rules are going to be met anyway, why not “just do it” and let countries join the euro without such conditions? The answer relates to our earlier discussion about inflation bias. If two countries with different inflation rates adopt a common currency, their inflation rates must converge—but to what level, high or low?

This makes the argument for the Maastricht criteria as a way of achieving credibility beautifully.

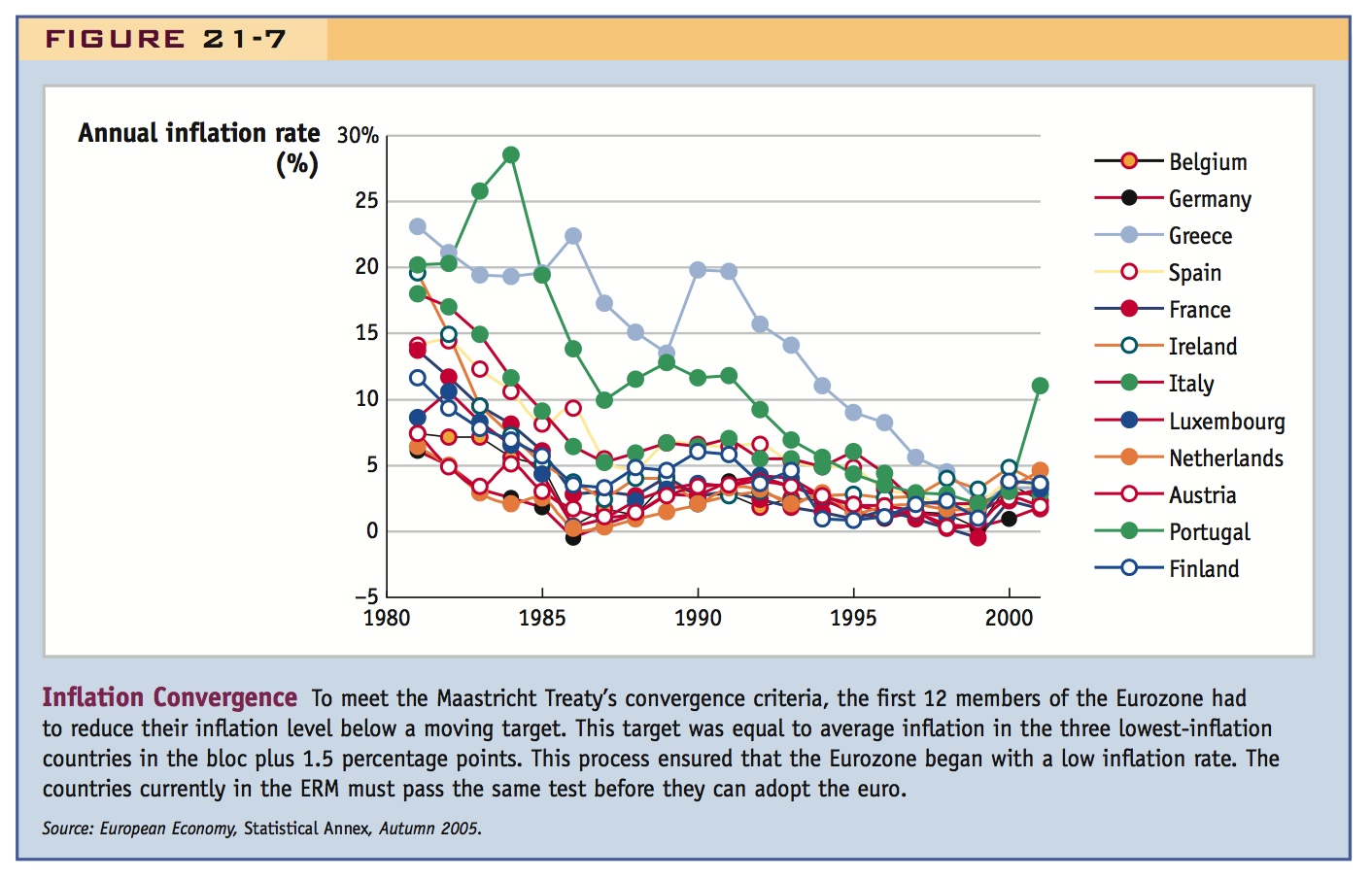

The way the rules were written forces countries to converge on the lowest inflation rates in the zone. We have argued that this outcome is needed for low-inflation countries to sign up, although it will require possibly painful policy change in the high-inflation countries. The Maastricht criteria ensure that high-inflation countries go through this pain and attain credibility by demonstrating their commitment to low inflation before they are allowed in. This process supposedly prevents governments with a preference for high inflation from entering the Eurozone and then trying to persuade the ECB to go soft on inflation. These three rules can thus be seen as addressing the credibility problem in a world of inflation bias. All current euro members successfully satisfied these rules to gain membership, and the end result was marked inflation convergence as shown in Figure 21-7. Current and future ERM members are required to go through the same test.

Fiscal Discipline The Maastricht Treaty wasn’t just tough on inflation, it was tough on the causes of inflation, and it saw the fundamental and deep causes of inflation as being not monetary, but fiscal. The other two Maastricht rules are openly aimed at constraining fiscal policy. They are applied not just as a condition for admission but also to all member states once they are in. The rules say that government debts and deficits cannot be above certain reference levels (although the treaty allows some exceptions). These levels were chosen somewhat arbitrarily: a deficit level of 3% of GDP and a debt level of 60% of GDP. However arbitrary these reference levels are, there still exist economic rationales for having some kinds of fiscal rules in a monetary union in which the member states maintain fiscal sovereignty.

Why might inflation ultimately be a fiscal problem? Consider two countries negotiating the treaty, one with low debt levels (e.g., Germany) and one with high debt levels (e.g., Italy). Germany has several possible fears in this case. One is that if Italy has high nominal debt (measured in lira, but soon to be measured in euros), Italy will lobby for high inflation once in the union (because inflation destroys the real value of the government’s debt). Another fear is that Italy has a higher default risk, which might result in political pressure for the ECB to break its own rules and bail out Italy in a crisis, which the ECB can do only by printing euros and, again, generating more inflation.

Although the independence of the ECB should weaken its power to lobby.

This might make more sense, but is again circumscribed by the ECB's independence.

430

The main arguments for the fiscal rules are that any deal to form a currency union will require fiscally weak countries to tighten their belts and meet criteria set by fiscally strong countries in order to further ensure against inflation.

Here, too, pick debate teams from the class to make both cases.

Criticism of the Convergence Criteria Because these rules constitute the main gatekeeping mechanism for the Eurozone, they have been carefully scrutinized and have generated much controversy.

First, these rules involve asymmetric adjustments that take a long time. In the 1980s and 1990s, they mostly involved German preferences on inflation and fiscal policy being imposed at great cost on other countries. Germany had lower inflation and larger surpluses than most countries, and the criteria were set close to the German levels, not surprisingly. To converge on these levels, tighter fiscal and monetary policies had to be adopted in countries like France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain while they tried to maintain the peg (to obey rule 1: staying in their ERM bands). As we saw in the chapter on output, exchange rates, and macroeconomic policy, fiscal contractions are even more contractionary under a peg than under a float. Such policies are politically costly, and hence the peg may not be fully credible. As we saw in the chapter on crises, foreign exchange traders often have doubts about the resolve of the authorities to stick with contractionary policies, and these doubts can increase the risk of self-fulfilling exchange rate crises, as happened in 1992. The same costs and risks now weigh on current Eurozone applicants seeking to pass these tests.

431

Second, the fiscal rules are seen as inflexible and arbitrary. The numerical targets have little justification: Why 3% for the deficit and not 4%? Why 60% and not 70% for the debt level? As for flexibility, the rules in particular pay no attention to the stage of the business cycle in a particular applicant country. A country in a recession may have a very large deficit even if on average the country has a government budget that is fairly balanced across the whole business cycle. In other words, the well-established arguments for the prudent use of countercyclical fiscal policy (including even nondiscretionary automatic stabilizers) are totally ignored by the Maastricht criteria. This is an ongoing problem, as we shall see in a moment.

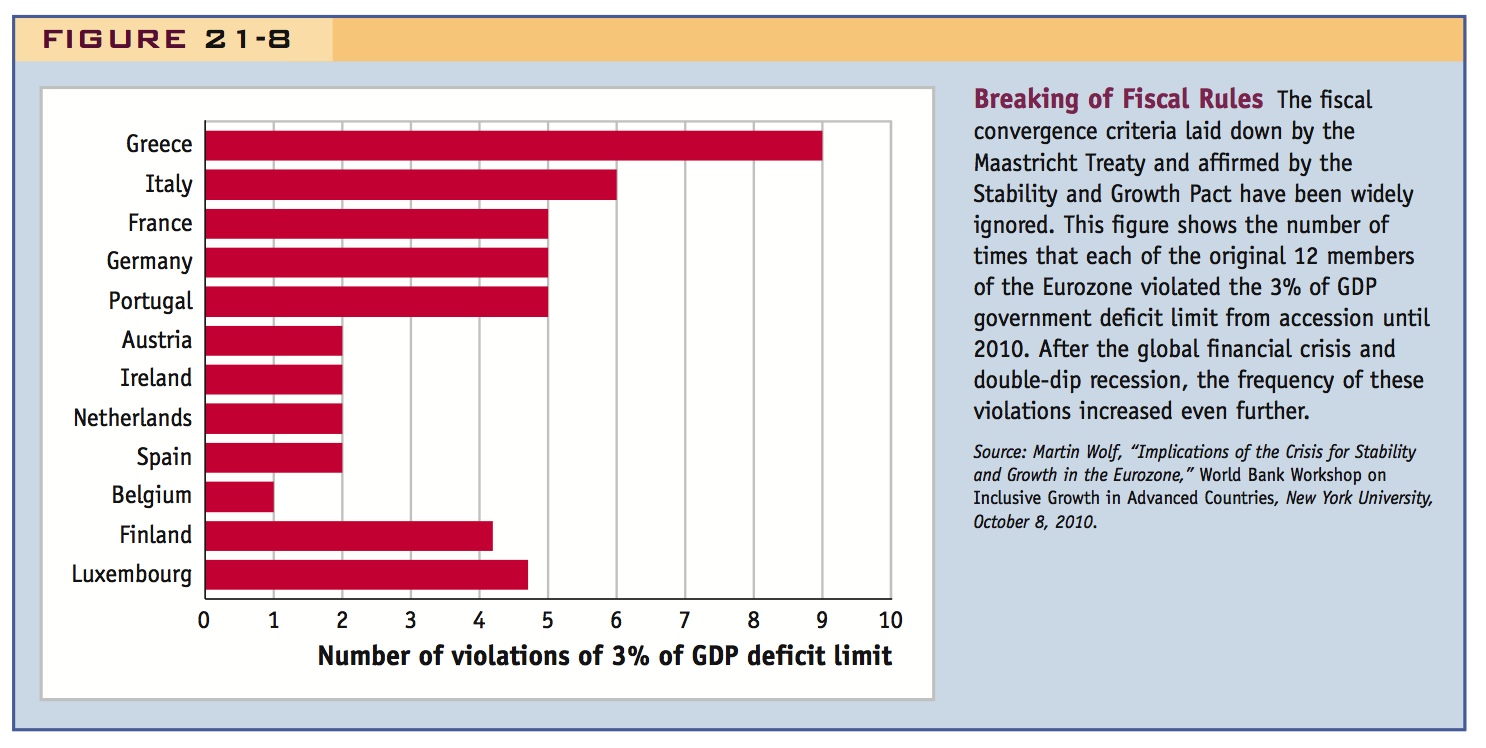

Third, whatever good might result from the painful convergence process, it might be only fleeting. For example, the Greek or French governments of the 1990s may have subjected themselves to budgetary discipline and monetary conservatism. Have their preferences really changed or did they just go along with the rules (or pretend to) merely as a way to get in? The same question applies to current Eurozone applicants. As Figure 21-8 shows, once the original dozen members of the Eurozone were in the club, their commitment to fiscal discipline (as reflected in their fiscal deficits) started to weaken in the subsequent decade, in some cases dramatically so.

Pose the question of whether these tests of credibility before the fact mean anything after the fact?

The problems just noted do not disappear once countries are in the Eurozone. Countries continue to have their own fiscal policies as members of the Eurozone, and they all gain a share of influence on ECB policy through the governance structure of the central bank. Countries’ incentives are different once the carrot of EMU membership has been eaten.

432

Sticking to the Rules

If “in” countries desire more monetary and fiscal flexibility than the rules allow, and being “in” means they no longer risk the punishment of being excluded from the Eurozone, then a skeptic would have to expect more severe budgetary problems and more lobbying for loose monetary policy to appear once countries had entered the Eurozone.

The answer: The ECB's independence achieves credible commitment to price stability. However, mechanisms to ensure adherence to fiscal criteria are inadequate.

On this point, as we see, the skeptics were to some extent proved right, but the problems they identified were not entirely ignored in the Eurozone’s design. On the monetary side, success (low and stable Eurozone inflation) would rest on the design of the ECB as an institution that could withstand political pressure and act with independence to deliver low inflation while ignoring pleas from member governments. In that respect, we have already noted the formidable efforts to make the ECB as independent as possible. On the fiscal side, however, success (in the shape of adherence to the budgetary rules) would rest on the mechanisms established to enforce the Maastricht fiscal criteria. This did not turn out quite so well.

The Stability and Growth Pact Within a few years of the Maastricht Treaty, the EU suspected that greater powers of monitoring and enforcement would be needed. Thus, in 1997 at Amsterdam, the EU adopted the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which the EU website has described as “the concrete EU answer to concerns on the continuation of budgetary discipline in Economic and Monetary Union.” In the end, this provided no answer whatsoever and even before the ink was dry, naysayers were unkind enough to term it the “stupidity pact.”

Throwing another acronym into the mix, the SGP was aimed at enforcing the 3% deficit rule and proposed the following to keep states in line: a “budgetary surveillance” process that would check on what member states were doing; a requirement to submit economic data and policy statements as part of a periodic review of “stability and convergence programs”; an “early warning mechanism” to detect any “slippage”; a “political commitment” that “ensures that effective peer pressure is exerted on a Member State failing to live up to its commitments”; and an “excessive deficits procedure” with “dissuasive elements” in the event of failure to require “immediate corrective action and, if necessary, allow for the imposition of sanctions.”15

The shortcomings of the SGP, which became clear over time, were as follows:

- Surveillance failed because member states concealed the truth about their fiscal problems. Some hired private-sector accounting firms to make their deficits look smaller via accounting tricks (a suspiciously common deficit figure was 2.9%). In the case of Greece, the government simply falsified deficit figures for the purpose of gaining admission to the euro in 2001 and owned up once it was in.

- Punishment was weak, so even when “excessive deficits” were detected, not much was done about it. Peer pressure was ineffective, perhaps because so many of the governments were guilty of breaking the pact that very few had a leg to stand on. Corrective action was rare and states “did their best,” which was often not very much. Formal SGP disciplining processes often started but never resulted in actual sanctions because heads of government in Council proved very forgiving of each other and unwilling to dispense punishments.

- Deficit limits rule out the use of active stabilization policy, but they also shut down the “automatic stabilizer” functions of fiscal policy. Recessions automatically lower government revenues and raise spending, and the resulting deficits help boost aggregate demand and offset the recession. This makes deficit limits tough to swallow, even if monetary policy autonomy is kept as a stabilization tool. In a monetary union, where states have also relinquished monetary policy to the ECB, the pain of hard fiscal rules is likely to be intolerable.

- Once countries joined the euro, the main “carrot” enticing them to follow the SGP’s budget rules (or to pretend to follow them) disappeared. Hence, surveillance, punishment, and commitment all quite predictably weakened once the euro was up and running.

These failures of the SGP came to light only gradually, but by 2003 the pact was in ruins, once it became clear that France and (ironically) Germany would be in breach of the pact and that no serious action would be taken against them. As we see next, fiscal problems in the Eurozone have only gotten worse, although whether the principles of the SGP can, or should, be reinstated is the subject of ongoing disagreement.