4 The Eurozone in Crisis, 2008–2013

European policymakers were concerned with hitting their inflation target and with the failure of governments to adhere to SGP fiscal rules. But they ignored other, dangerous developments.

1. Boom and Bust: Causes and Consequences of an Asymmetrical Crisis

Focusing on price stability, the ECB paid little attention to financial stability. Some peripheral countries were enjoying booms (and real estate bubbles) financed by heavy borrowing from Northern countries. There was an asymmetric boom. Then came the global turndown. The bubbles collapsed and construction and wealth failed. Meanwhile households were saddled with high debts, and wages were so high as to be uncompetitive. The economy contracted, banks cut lending, and saw many of their loans go bad. Core countries responded by tightening credit.

a. The Policymaking Context

The policy response was timid and quickly reversed. Why? (1) The ECB was obsessed with inflation, and limited in its ability to make loans to act as a lender of last resort. (2) There was no transfer mechanism to shift resources to members in need. They had to borrow from the EU, ECB, and IMF, which in turn demanded austerity policies that made the recession worse. (3) There was no banking union, so responsibility for rescuing insolvent banks was left to the member states. (4) Since there was no banking or fiscal union, sovereign debt was held by central banks of the members. Propping up the banks in turn jeopardized the creditworthiness of the sovereign; at the same time, the decline in the value of sovereign debt hurt the balance sheets of the commercial banks. (5) Labor in Europe is immobile, so unemployment rates stayed very high. (6) Uncertainty about economic conditions caused capital flight.

b. Timeline of Events

A detailed chronology of events starting from April 2010 (when Greece first asked for help) through March 2013 (when Cyprus imposed taxes on bank deposits).

c. Who Bears the Costs?

The core countries made little effort to help the periphery, and expect their debts to be repaid in full. Peripheral countries could have been allowed to default. Instead, the EU provided bailouts to banks or governmental creditors. To prevent peripheral countries from defaulting, the ECB was forced to lend to banks against the weak collateral of the debtor governments bonds. Draghi famously promised to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro. But Germany is opposed to this since it might monetize debts and cause inflation.

d. What Next?

Europe needs plans to recapitalize weak banks and restore fiscal stability of governments. Yet the policy response of the EU and ECB has been confused and, as of 2013, it still wasn’t clear if losses would be recognized or written down. Meanwhile, austerity policies were implemented to repay the debts, unemployment in the stricken countries increased, and political unrest grew. In addition, ECB monetary policy was still fairly tight and most EU also implemented austerity policies, reducing growth even more. Europe as a whole went into a recession. The peripheral countries need to grow to service their debt, but where will this come from? Neither C nor G can pick up. I might increase, and exporting might help. However the latter normally requires depreciation, which is not an option in the euro. Alternatively, they must lower wages and costs to regain competitiveness, a painful process that rarely works. It imposes real social and political pain, but also entails a deflation that could prolong the recession and raise debt burdens. Austerity policies make things worse. Peripheral countries may withdraw from the zone after. Core countries might also take losses if they prop up the system, and balk a “transfer system” to help the periphery. The zone itself may be in peril.

For almost 10 years, Eurozone policy making focused on two main macroeconomic goals: the ECB’s monetary policy credibility and inflation target, seen as a broad success given low and stable inflation outcomes; and the Eurozone governments’ fiscal responsibility, seen as a failure given the general disregard for the SGP rules. However, policy makers (like their counterparts all over the world) failed to spot key macroeconomic and financial developments that were to plunge the Eurozone into crisis in 2008 and beyond.

Boom and Bust: Causes and Consequences of an Asymmetrical Crisis With a fanatical devotion to inflation targeting, the ECB (and its constituent central banks) paid insufficient attention to what was historically a primary responsibility of central banks, namely, financial stability. Within some parts of the Eurozone (as elsewhere) borrowers in the private sector were engaged in a credit-fueled boom. In other parts of the Eurozone, savers and banks funneled ever more loans toward those borrowers. The creditors were core Northern European countries like Germany and the Netherlands; the debtors were fast-growing peripheral nations such as Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain (so called because they are located geographically on the periphery of Europe).

In Greece, much of the borrowing was by a fiscally irresponsible government that was later found to be falsifying its accounts. In the other peripheral nations, however, the flow of loans funded rapid investment and consumption surges, including a residential construction boom that in places (e.g., Dublin and Barcelona) rivaled the property bubble in parts of the United States. In Ireland and Spain, even as this boom took place, the governments had maintained a fiscal position close to balance, or even surplus; the asymmetric boom helped them at that time. The trouble was to come when the boom gave way to a severe asymmetric bust.

434

Growth slowed sharply when the global boom turned to a bust that dragged Europe down with it. Much of the construction and overconsumption in the peripheral economies turned out to be unjustified and unsustainable. Along the way, however, the boom had bid up the prices of assets (notably houses) and of many nontraded services (and thus wages), and had left households in the peripheral nations saddled with high debts and uncompetitive, high wage levels that could not be sustained once the artificially high demand of the boom years was exhausted. These events were bad enough, but other factors made things worse.

A vicious spiral began in the peripherals. Construction and nontraded sectors started to collapse, which lowered demand. House prices fell, as did the value of firms. Wealth collapsed, lowering demand further. Output fell in the short run, as did tax revenues. Households cut spending further, and the governments also tightened their belts. With everyone suffering lower incomes and wealth, and the economy contracting, banks tightened lending, which hurt demand still more. As the spiral continued, banks found that their loans were often turning bad, and that many debts would be repaid only partially if at all. Because much of the periphery’s lending came from banks connected to the Northern European core, these developments triggered tighter credit everywhere in the Eurozone as banks turned cautious. Lending growth for the whole Eurozone was virtually frozen for five years.

Follow this section in providing a brief survey of the problems of the last few years. Focus upon these institutional features that made it difficult for the Eurozone to respond effectively.

The Policymaking Context The Eurozone faced hard choices after the crisis hit in 2008, but the policy measures taken were more timid and quickly reversed, as compared with actions in other countries.

Why? The choices made can potentially be explained by considering the unique features of the European monetary union. We highlight six points.

- Limited Lender of Last Resort The Eurozone is a monetary union, and has a common central bank, but the ECB is highly inflation averse, is restricted from direct government finance, and is required not to engage in lender of last resort actions to banks lacking good collateral. It is therefore unwilling to intervene with emergency liquidity in weak local banks, except with strict guarantees from the local sovereign government; and it has been generally unwilling (with some exceptions) to intervene to ensure weak sovereigns remain funded at sustainable interest rates.

- No Fiscal Union The Eurozone lacks a political-fiscal union, and has no fiscal policy tools, because there is no central budget that can be used to engage in cross-country stabilization of shocks. This is in large part due to the absence of a central European government (executive power) standing above the sovereigns (the member states). In contrast, in the United States, with a strong center, substantial federal-level automatic transfers between states act as a significant buffer. In fact, the Eurozone has the reverse problem: when the national sovereigns lose credit market access on reasonable terms, they must beg for assistance from the EU, ECB, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As a condition for granting assistance, these organizations have imposed harsh terms that require the countries to undertake fiscal contractions during their slumps, amplifying their business cycle. Overall, even for countries not in a rescue program, the EU authorities have sought even stricter fiscal rules and monitoring since the crisis, adding new stringencies for all countries on top of the Maastricht and SGP protocols.

- No Banking Union The Eurozone also lacks even the minimal political-fiscal cooperation to create a banking union, meaning that responsibility for supervising banks, and resolving or rescuing them when they are insolvent, rests with national sovereigns. In the United States, in contrast, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and other institutions underpin a true federal-level banking union with a common pool of fiscal and monetary resources. Critically, the insurance of an individual U.S. state’s banking system does not depend at all on the fiscal position of the state itself.

- Sovereign-Bank Doom Loop Because there isn’t a banking union or a political-fiscal union, a Eurozone country’s national banks tend to hold the local national sovereign’s debt; but, in turn, these sovereigns can end up bearing large fiscal costs to repair banking systems and protect depositors from losing their money. The banks and the sovereign can then enter into a so-called “doom loop”: weak banks’ losses can damage the sovereign’s creditworthiness just when it may need funds to resolve a crisis; simultaneously, a weak sovereign’s debt can decline in value, damaging the balance sheets of local banks where such local debt is predominantly held. In contrast, there is no local U.S. doom loop: a California bank does not hold California debt, and a California bank failure would not burden the state itself.

- Labor Immobility Because the Eurozone is especially weak on labor mobility (one of the OCA criteria), a local economic slump (say, in Spain) is likely to persist for longer because unemployed workers cannot migrate easily to another country where there are better opportunities. After the crisis, local long-term unemployment rates (especially among the youth) rose to very high levels in some countries, despite stronger economic conditions in the core Eurozone countries. The United States saw more labor migration between asymmetrically affected areas in its slump.

- Exit Risk We know that after barely more than a decade, the credibility of the Eurozone as permanent, with no possibility of exit, is not 100% certain. Events have shown that the risk of a country’s exit can put financial pressure on that country. If investors suspect that a country will exit the Eurozone, they will want to pull their money out of the country’s banks and sell its debt, to avoid potential losses. The result is capital flight to safe havens, and higher risk premiums on local interest rates. These reflect the nonzero “redenomination risk” of local assets out of euro and into a new, and much depreciated, local currency plus the risk of losses of depositors via bank restructuring. This dynamic was much in evidence in Cyprus in 2013, for example.

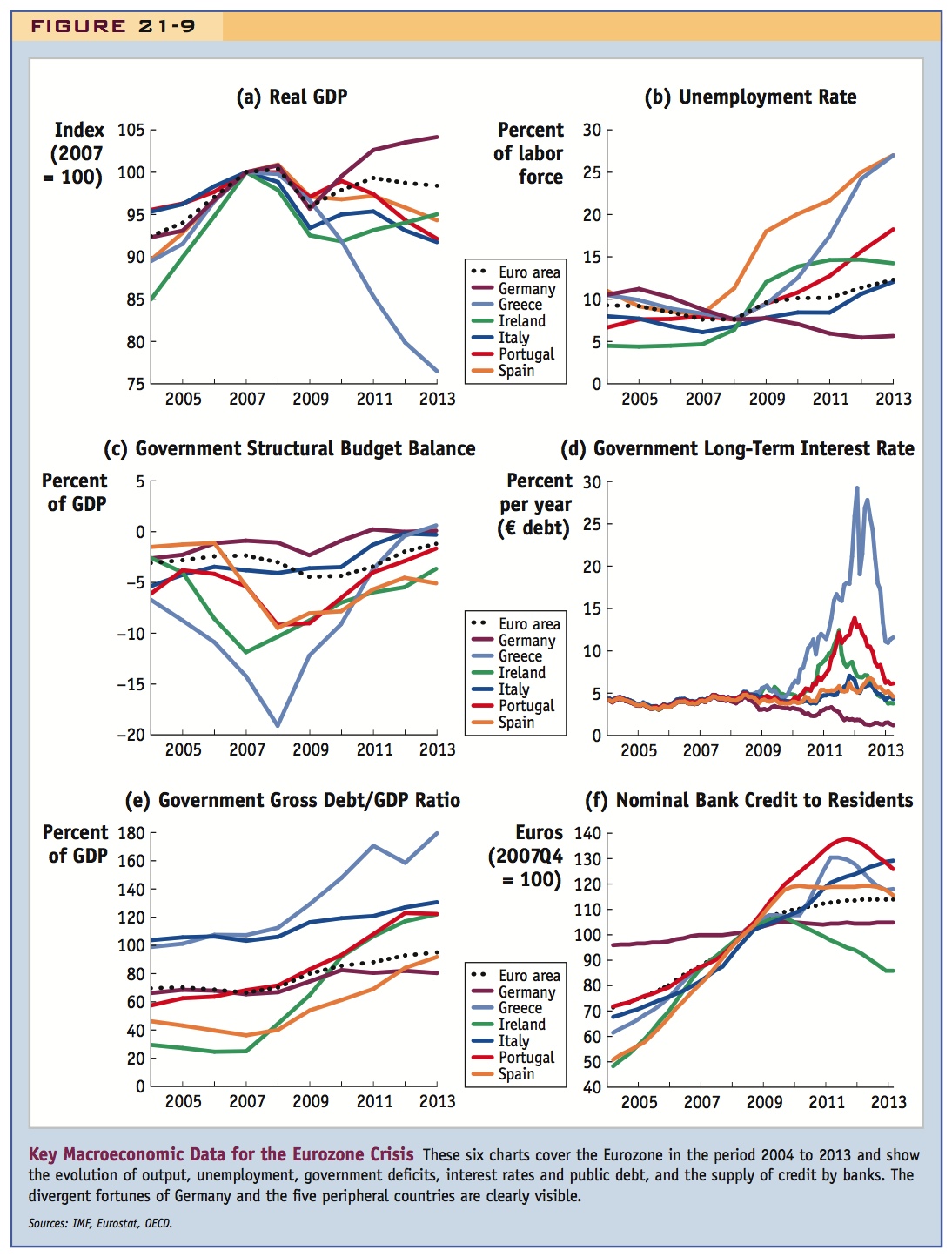

Many of the events in the timeline of 2008–13 can be better understood if we keep these six major points in mind. We now take a closer look at this period, with some key macroeconomic data present for reference in Figure 21-9.

Timeline of Events The first big problem occurred in April 2010 when Greece requested help as its country risk premium spiked and it could no longer borrow at sustainable rates, an action that roiled global financial markets. The EU/ECB/IMF troika jointly devised a plan to stave off the disaster of an uncontrolled default–cum–banking crisis. Together, the troika would provide €110 billion of loans that would give Greece two to three years of guaranteed funding. This help would only be provided under strict conditions that the Greek government radically cut its spending. Financial market turmoil continued, however, and the troika announced further measures for Greece on May 7, 2010.

436

437

To help other troubled nations (Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Italy were all at risk), all EU countries established a fund to provide loans of up to €440 billion. This fund, now known as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), was founded on the good credit of the other EU members and was backed by a once unimaginable bond-buying commitment from the ECB. In addition, funds of up to €60 billion from the EU budget provided a theoretical credit line of up to €500 billion. A further sum of €250 billion was pledged by the IMF. The troika believed that these funds would be large enough to cope with any financing problems that might arise in Ireland and Portugal. If financing problems had occurred in larger countries like Spain (or, even worse, Italy), the troika would have had to come up with more resources.

The announcement of these measures kept the panic under control only for a time. The risk premiums of the peripherals spiked again in November 2010, after EU leaders said they wanted to possibly impose losses on bondholders in any future rescues. When the EU leaders made this announcement, financial markets realized that they could suffer losses not only on their Greek bonds but on their bonds issued by other weak countries on the periphery. Even though the EU officials backtracked, the financial markets continued to worry and the borrowing costs for all peripherals started to climb. As their borrowing costs rose, they too lined up to seek official bailout programs from the troika, often under some duress.

The troika thought their official funding would help keep the periphery countries governments afloat until they could get back on their feet again. But Greece’s debt was so high that it eventually had to impose a partial default in February 2012. During May and June of 2012, many thought that Greece was on the verge of exiting the Eurozone and there was further turmoil in financial and political circles. Greece remained in the Eurozone, but by 2013 the Greek unemployment rate was 27%; among youths, the unemployment rate was 58%.

By mid-November 2010, Ireland approached the troika to ask for an ESM program, which further shook confidence in the peripherals and in the euro itself. The Irish had a self-made problem. In 2008–09 Ireland guaranteed the safety of deposits in their private banks to prevent bank runs by bank debt holders that would cause even more economic pain. This method of preventing bank failures did not solve the problem of the private losses, it just transferred the financial sector’s massive losses to the government. By late 2010, the Irish government had to admit a loss of about 20% of GDP just to cover the banks’ bad debts. The overall fiscal deficit for Ireland that year was an unheard-of 32% of GDP. Financial markets got scared, and the Irish government’s interest rate climbed astronomically. They too were pushed into a program of harsh austerity involving public sector cuts and higher taxes. Unemployment rose from 4% in 2006 to 15% by 2012, and among youths it rose to 30%. Ireland was not able to borrow affordably in financial markets again until July 2012, but the economy remained weak.

Spain also faced a banking crisis, and although the Spanish government did not intervene as quickly or as generously as the Irish government, the losses could not be hidden forever, and the country’s economy suffered. Banking systems in countries like Spain and Ireland have become so impaired that they do not lend much, and when they do, they do not pass on the ECB’s low interest rates to local borrowers: the monetary policy transmission mechanism is broken as low ECB interest rates are not passed through to local firms and consumers. The banks may try to survive as “zombie banks,” but they do not help the real economy very much. Similar banking stresses occurred in Portugal and Italy, and by 2013 the interest rates at which Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian firms could borrow from their countries’ banks were 2 to 3 percentage points higher than the rates available to German or Austrian firms, causing even greater asymmetry.

438

Even though Portugal and Spain were not initially as damaged as Greece and Ireland, they shared in the collapse of economic growth in the Eurozone periphery. Spain’s banking losses were continually revealed to be larger than previously admitted, and Portugal’s growth rate—already bad before the crisis—got even worse. The continuing deterioration in fiscal conditions caused their lending rates to rise, so that in 2011 and 2012 Portugal and Spain, respectively, also reluctantly entered into bailout programs. By 2013 Spanish unemployment reached 27%, and 56% among youths; in Portugal the rates reached 11%, and 38%, respectively.

As of mid-2013, the latest country to enter an official bailout program was Cyprus, a small but telling example of how the Eurozone might cope with further distress. Cyprus had its own boom and bust, a housing bubble of sorts that had been fueled by an influx of foreign wealth (much of it Russian) seeking a safe, offshore tax haven. Cyprus’s economy stalled in 2011 after its government credit rating had been downgraded. By 2012, banking problems in Cyprus were apparent: Cypriot banks still held significant Greek debt, and were badly hit when the troika decided to allow a Greek default. As early as July 2012 Cyprus began months of confusing and contentious negotiations with the troika. As rumors emerged that bank depositors might suffer losses, a slow bank run developed in late 2012 and early 2013.

As it turns out, the rumors were well founded. On an extraordinary weekend in March 2013 the troika and the Cyprus government talked long into the night and finally made a deal that would impose significant “taxes” on all bank deposits, including those below the EU’s legally guaranteed level of €100,000. All hell broke loose: angry protests began, people tried to get their money out of the banks and out of the country, parliament rejected the deal, and it took another weekend to sort out a different compromise that protected those with less than €100,000 in the bank, but imposed losses on everyone else. Along the way, the government maneuvered around other laws and treaties: it imposed capital controls on banks and at the border, and also shunted aside the priority of depositors and creditors at Laiki Bank and Bank of Cyprus (so that the ECB would be made a preferred creditor ex post—its loans to Laiki, secured with specific collateral, would be transferred whole, without losses, and the losses would be forced onto other secured and unsecured debts of the bank’s large creditors, and, remarkably, those of the impaired-yet-acquiring Bank of Cyprus, too). Even though the entire operation was widely judged a political and economic disaster, the President of the Eurogroup (the organization of Eurozone finance ministers) described the outcome as a “template” for handling future crises, a view echoed by ECB President Mario Draghi some days later.

Who Bears the Costs? The view that countries should bear all of the pain for their crises is a consequence of the weak level of cooperation and collective burden-sharing in the Eurozone project. As we have noted, this is very different from the U.S. monetary union where political, fiscal, and banking union structures work together to help spread risks and absorb shocks. The core countries of the Eurozone have made little effort to provide assistance to the peripherals, beyond lending them money which will supposedly have to be paid back one day. The belief has been that every country is responsible for its own fiscal position.

439

But there is some inconsistency in the Eurozone’s approach. Note that in principle the governments (and the banks) of the peripherals could have been allowed to default, and resume operation in a more creditworthy state. Instead, the EU decided on a “moral hazard” or “bailout” approach of trying to ensure that no bank or government creditors were ever hurt. This controversial step had several motivations, many of them understandable, including the desire to protect core EU banks, to protect the collateral of the ECB, to avoid further contagion and panic in financial markets, and perhaps to defend the reputation of the euro as a serious global currency. These decisions cast aside the prior notion that every Eurozone country was responsible unto itself and the idea that the ECB would not go along in any bailouts. Politically, this course of action would bring about much greater centralization of power, with the European and/or IMF authorities dictating more and more terms on which periphery countries in official bailout programs could run their economic policies.

Since the EU leadership desperately wanted to prevent any country from defaulting, the ECB (like central banks in centuries past) became the only Eurozone institution willing and able to lend a hand. The ECB continued to lend to the private banks against the ever-weaker collateral of the peripheral governments’ bonds. Prior to the crisis, the ECB had supposedly said it would refuse to lend against such government bonds when their ratings fell, but when push came to shove, the ECB relaxed its lending criteria again and again, because to do otherwise would have triggered a funding crisis for both the banks and their respective governments. By 2012, new ECB President Mario Draghi was promising to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, but it isn’t clear what he meant by that statement. We still do not know, for example, the exact scope and terms of the Outright Monetary Transactions program, a proposed ECB bond-buying program. But some Eurozone officials, such as German Bundesbank head Jens Weidmann, are not eager for the ECB to act as a backstop in government bond markets. He and others fear that undertaking such programs will lead to fiscal dominance, money printing, and inflationary budget financing.

What Next? To the skeptical, the Eurozone/ECB approach has been a giant “extend and pretend” refinancing scheme to postpone tough choices at the nexus of monetary, fiscal, and banking policies. Given the dismal growth path that is expected to continue into the future, the approach will likely fail unless it makes a plan to write down or restructure the underlying losses of banks and governments in the periphery, and even some in the core. The Eurozone needs to have plans and policies in place that will allow it to recapitalize failing banks and restore fiscal health to the governments.

The EU, ECB, IMF, and all of the Eurozone’s member governments have been slow to understand (or even agree on) what is happening, and so it has been difficult for them to figure out what to do. As a result of this confusion, they send different signals to different program countries at different times. As of 2013 it remains unclear how these losses will be finally recognized, and the uncertainty created by the Cyprus crisis has done nothing to clarify the matter, as now even humble bank depositors feel themselves to be in the firing line. In addition, political and social unrest remains high, which is hardly surprising given the persistently high levels of unemployment and stagnant living standards. New loans continue to roll out, or rollover, in the program countries, but their debt-to-GDP levels remain high and rising. Yet one way or another, through cuts in public spending, losses for depositors, levies for taxpayers, defaults or inflation for bondholders, or all of the above, the losses will eventually be felt and dealt with. We just don’t know how the story will end yet.

440

A sudden growth miracle could quickly erase all of these problems. But many even doubt whether the current policies will be enough to maintain stability and prevent a continued long depression in the short to medium term. The ECB monetary policy stance changed little in 2010–13, but the governments of the Eurozone turned very hard in the direction of fiscal austerity, which led to a change in the total Eurozone government structural budget surplus of between 3 and 4 percentage points of GDP from 2010 to 2013.

Not coincidentally, in late 2011 the Eurozone went into a double-dip recession, and by early 2013 had recorded six straight quarters of negative growth. Measured from the last peak in output, the slump had dragged on in Europe for about as long as the Great Depression of the 1930s. To service their large euro-denominated debt, program countries like Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Cyprus need to see their economies recover and their nominal GDP grow (as measured in euros). In the near term, however, growth forecasts for these economies are dismal. Their real economies continue to shrink, and neither private nor government consumption will provide any relief. Investment might eventually pick up a little and bring about some economic growth (after all, the capital stock is slowly wearing out). A rise in net exports would seem the best hope, but this would normally require a real depreciation in a nation’s currency. Because peripherals have no currencies to depreciate (they use the euro), the only way they can restore competitiveness and output is by a large decline in wages and costs, a tough process that is rarely successful, and which is being forced along by high unemployment. In addition to severe social and political pain, this harsh deflation may keep nominal GDP low and falling for a long time, causing the countries’ debt burdens to grow ever larger as a fraction of income, despite their best efforts to cut government expenditures. By lowering demand and increasing unemployment, the austerity-under-duress undertaken by the peripherals may have been self-defeating.

If all these efforts to keep the Eurozone intact fail, and if political will evaporates, one or more peripheral countries may default, and even exit the Eurozone. In that event, huge economic sacrifices and deep social damage will have been imposed on their populations, seemingly for nothing. Core countries may also take large losses if they attempt to prop up the system, and they could balk at a “transfer union” based on payments to a group of peripherals to defend the honor of their single currency project. If uncontained, the potentially serious side effects of such an event would surely be an adverse shock for the global economy, but they would be an incredibly serious crisis for Europe itself. Should a scenario like this unfold, tensions will rise, and the Eurozone in its present form might be in peril (see Headlines: A Bad Marriage?).

441