4 The Global Macroeconomy and the 2007–2013 Crisis

This is a nice, short but comprehensive narrative of recent events. Students will like it a lot. Look for places where you can link specific ideas or incidents, things you've covered in previous chapters.

1. Backdrop to the Crisis

a. Preconditions for the Crisis

For a decade prior to the crisis, there was a massive increase in saving by emerging market (EM) economies. They were already saving a lot, but then saved even more as a form of self-insurance after the currency crises of the 1990s. Part of the saving came from the private sector, but increasingly it took the form of the accumulation of external reserves by EM central banks. Their lending created “global imbalances,” with EMs running large CA surpluses, mirrored in CA deficits for developed market (DM) economies. This global saving glut had perverse consequences: On the one hand, EMs were now lending, when normally they should have been borrowing to finance investment. On the other hand, DMs now enjoyed very low interest rates that financed consumption and investment. Unfortunately, the credit boom increasingly financed risky investments of dubious quality.

b. Exacerbating Policies and Distortions

These can all be debated, but just for starters: (1) China and other Asian countries intervened in the FX market to keep their currencies undervalued. This promoted exported-lead growth: Western countries were happy to go deeper into debt to buy more of the cheaper Asian manufactured goods. Rebuttal: there isn’t much evidence that their currencies were much out of line. (2) The Fed kept interest rates too low for too long, fueling a real estate bubble. Meanwhile, the ECB kept interest rates low too, starting bubbles in Ireland and Spain. Rebuttal: at the time the Fed seemed to pursuing its dual mandate successfully, and it is easy to find fault ex post. (3) After the wave of financial deregulation that began in the 1970s, there was inadequate supervision and regulation of banks and the financial sector. Rebuttal: The problem was not that regulation changed, but that financial innovation outpaced them. (4) The government implemented variety of policies that produced perverse effects. For example, Fannie Mae and Freddie purchased or guaranteed a lot of the mortgages that went bad; “too big to fail” policies create moral hazard problems leading to excessively risky investments. Rebuttal: Most of the credit markets were not directly affected by the government. (5) Financial markets may be subject to various sorts of market failure, including investor irrationality, herd behavior, imperfect information, and asymmetric information, that may contribute to crisis: Rebuttal: Even if this is true, it is hard to spot a bubble ahead of time.

c. Summary

Historically, economies based upon financial capitalism are subject to periods of financial instability. The strict financial regulations imposed in the wake of the Great Depression reduced this instability, but the financial deregulation after the 1970s brought it back. Then the credit bubble burst, leading to the worst recession since the Great Depression.

2. Panic and the Great Recession

The quality of residential mortgages declined, so mortgage delinquencies increased. Large banks, investment banks, and insurance companies started to take losses.

a. A Very Modern Bank Run

Since these institutions were so inadequately capitalized, it got harder for them to borrow from each other. This meant they had to shrink their balance sheets by reducing their loans and by selling securities, depleting their capital. Some failed; others were purchased cheap in takeovers.

b. Financial Decelerators

The financial crisis affected the real economy through the financial decelerator: It became harder to borrow, so firms couldn’t finance their day-to-day activities or invest; the fall in wealth reduced consumption and investment as households and firms tried to rebuild it. The stock market fell, reducing wealth still more.

c. The End of the World Was Nigh

The stock market fell until 2009. By then, three of the biggest investment banks had failed or been taken over. The U.S. and Britain implemented plans to recapitalize the banks. Meanwhile, most countries initiated stimulatory fiscal policies, and monetary policies lowered interest rates to almost zero. Credit started to recover, and incomes and trade volumes stopped falling. There have been huge costs: a large decline in output, and a dramatic increase in unemployment that will last for years, the worst recession since the Great Depression, in addition to the costs of recapitalizing the banks (in Britain), and increased government debt.

d. Europe

In Ireland, the bubble burst and the economy went into recession. Likewise for the Baltic states, Greece, Spain, and Portugal. Greece and Portugal had chronic, large fiscal deficits and already steep risk premia; Spain and Ireland were unfairly mixed with them in the PIGS group and also saw steep increases in risk premia. They avoided insolvency only through loans from the ECB, EU, and IMF. Still the debt burden for Greece was too high, so it defaulted and restructured it in 2012. Spain and Italy came under pressure too. Finally, Draghi announced he would do whatever it takes to prop up the euro—meaning presumably that the ECB will act to prevent sovereign defaults. But the whole episode raises deep and pressing questions about European fiscal policies, the regulation of cross-border banking and finance in Europe, and the viability of the euro itself.

e. The Rest of the World

The impact of the crisis was smaller outside the U.S. and the Eurozone. EMs recovered quickly, and suffered no banking, currency, or default crises.

f. The Road to Recovery

By 2013, the U.S. was recovering, but Europe and Britain were still in recession. Risks: (1) In the U.S. the fiscal stimulus ended and was followed sequestration; in Europe many countries imposed austerity policies. These could slow the recovery. (2) Central banks are operating at the zero interest lower bound, so conventional monetary policy—working through short-term interest rates—isn’t working. (3) The unconventional policy measures used by the Fed—quantitative easing (QE) in different incarnations—have increased the Fed’s balance sheet. They involve a new form of involvement in the financial markets that is controversial; it could also weaken the dollar, which makes other countries anxious. (4) How the Fed will exit from QE is not clear. On the one hand, can this be achieved without risking inflation? On the other hand, can it be achieved without raising interest rates too far, too fast and so causing bankruptcies and defaults? (5) In Europe growth was still weak in 2013. Austerity policies were still in effect. The ECB was providing liquidity, but otherwise there was no clear strategy. (6) All of the DM came out of the crisis with higher private and public debt. Conversely, EMs were growing rapidly, but through rapid private credit growth that was starting to falter.

3. Conclusion: Lessons for Macroeconomics

The crisis is still not over, and it will take a long time to assess its consequences. However, it is already affecting the way we study macroeconomics: (1) It is highlighting the defects of some standard models: We can’t focus on the real side of the economy and ignore the financial sector; we need to re-integrate money and banking into our macro models; we need to focus on how the demands for money and financial assets change in time of crisis; we need to incorporate irrational herding, limits to arbitrage, moral hazard and imperfect information. (2) Policy needs to be reconsidered: Should central banks be concerned about financial stability as well as price stability and full employment? Should they focus narrowly upon interest rate policy, or should they shoulder broader macro-prudential goals? (3) Arguably, we wouldn’t have been quite so surprised by the crisis if we had paid greater attention to its historical precedents. Perhaps economists should reacquaint themselves with history.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007–09 and the associated Great Recession constitute one of the most significant global macroeconomic events of modern history. Even now, when the full implications are as yet unclear, we may anticipate that when these times are assessed by economic historians in the distant future, they will probably rank in the memory not far behind such momentous events as the 1930s Great Depression. And already, looking only to the very near future, in terms of the economic damage created, the current recessions will not be forgotten quickly by our generation of households, firms, banks, or governments, all of whom have been affected by the downturn, and many of whom have endured serious suffering.

In this section of the chapter, we look at the crisis using the tools of international macroeconomics developed throughout this book. We begin by looking at the origins of the crisis not only in events of the previous decade, but also as part of longer-term trends in the U.S. and global economies. We then look at the Great Recession itself, how events unfolded, and what we can learn about the economic shocks and policy responses. Next, we look at how the global economy can recover from this shock, a process that was under way, but still fragile and with a long way to go as this chapter was written in late 2013.

Macroeconomists have much to learn from the crisis. Some key macro-financial and policy issues have been known about since the early 1800s, but they had been ignored or forgotten by many economists, and more future research is likely to focus on these important issues.

Backdrop to the Crisis

Several features of the precrisis global economy can help us understand some of the calamitous events that were to follow. Keep in mind, however, that the benefits of hindsight should not cause us to underestimate the difficulties observers had in understanding these developments as they were unfolding at the time. Although a number of these trends were recognized by some observers as problematic, opinions were split as to whether any one of these issues was serious enough to justify any corrective action prior to the crisis.

494

This article argues that the IMF is the world’s “fire brigade” in times of crisis.

Is the IMF “Pathetic”?

The IMF is the closest thing to a global lender of last resort. When times are calm, it may be tempting to think of abolishing the institution. As this precrisis column pointed out, to have done so would have been a remarkably complacent idea.

Meral Karasulu did what any seasoned International Monetary Fund staffer would do: She grinned and, for the umpteenth time, listened to suggestions that the institution was to blame for the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

“Thank you for your question,” she replied to an audience member at a May 14 EuroMoney conference in Seoul. Then, she launched into a defense of the IMF’s actions.

As the IMF’s representative in South Korea, Karasulu is used to the drill. After all, many Koreans routinely refer to the “IMF crisis.” It’s a reminder that a decade after Asia’s turmoil, the IMF is still explaining itself wherever it goes.

Three weeks after the Seoul conference, there was similar griping at an event I attended in Buenos Aires. The mood had barely changed since March 2005, when President Nestor Kirchner scored points with many of Argentina’s 40 million people by calling the IMF “pathetic.” He has been demanding that the institution stop criticizing the Latin American country.

Korea and Argentina have little in common. Yet Korea is among the nations stockpiling currency reserves to avoid having to go to the IMF for a bailout ever again. Argentina, meanwhile, continues to tout the end of its IMF-backed program last year as an economic victory.

This column isn’t a defense of the IMF’s actions during the Asian crisis or Argentina’s in the early 2000s. The Washington-based fund has a small army of well-compensated people to do that. And the IMF has had its fair share of blunders, including telling Asian countries to tighten fiscal policy during a crisis.

Yet all this talk of IMF irrelevance is overdone. What’s more, the chatter suggests the creation of a new bubble called complacency.

“It’s ironic to my mind that people say the fund isn’t needed anymore because nothing in the global financial system is broken at the moment,” John Lipsky, the IMF’s first deputy managing director, said in an interview last month in Tokyo. “It strikes me we are trying to anticipate and prepare for when things may go wrong again.”…

Sure, Asia has insulated itself from markets with trillions of dollars of currency reserves. The IMF’s phones may be ringing off the hook if China’s economy hits a wall, the U.S. dollar plunges, the so-called yen-carry trade blows up, a major terrorist attack occurs, oil prices approach $100 a barrel or some unexpected event roils world markets.

The thing is, the IMF and its Bretton Woods sister institution, the World Bank, have scarcely been more necessary. How efficient and cost-effective they are is debatable; what’s not is that today’s global economy needs the buffering role that both of them play….

The IMF was never set up to play the role it did during crises in Mexico, Asia and Russia in the 1990s and turmoil in Latin America since then. Even so, it will be called upon the instant a crisis in one country spreads to another. As imperfect as the IMF is, the world needs the economic equivalent of a fire brigade when markets plunge.

There’s much chatter about how global prosperity is reducing the need for billion-dollar IMF bailouts. As of March, IMF lending had shriveled to $11.8 billion from a peak of $81 billion in 2004. A single nation, Turkey, accounted for about 75 percent of the IMF’s portfolio.

Isn’t that a good thing? The IMF is like a paramedic: You hope you won’t need one, but it’s great that one is just a phone call away. Plenty of things could still go awry and necessitate a call to the IMF….

Complacency looms large in today’s world. All too many investors think the good times are here to stay and all too many governments are ignoring their imbalances for similar reasons….

All this means that, far from being irrelevant, the IMF may be in for a very busy couple of years.

Source: Extract from William Pesek, “Is IMF ‘Pathetic’ or Just Awaiting Next Crisis?” bloomberg.net, June 12, 2007. Used with permission of Bloomberg L.P. Copyright © 2013. All rights reserved.

495

Preconditions for the Crisis The global financial crisis was primarily a story of investments turned bad, that is, of savings unwisely allocated. To get a sense of what fueled the boom and bust cycle, it is worth asking where those savings materialized at a global and macroeconomic level and where they ended up.

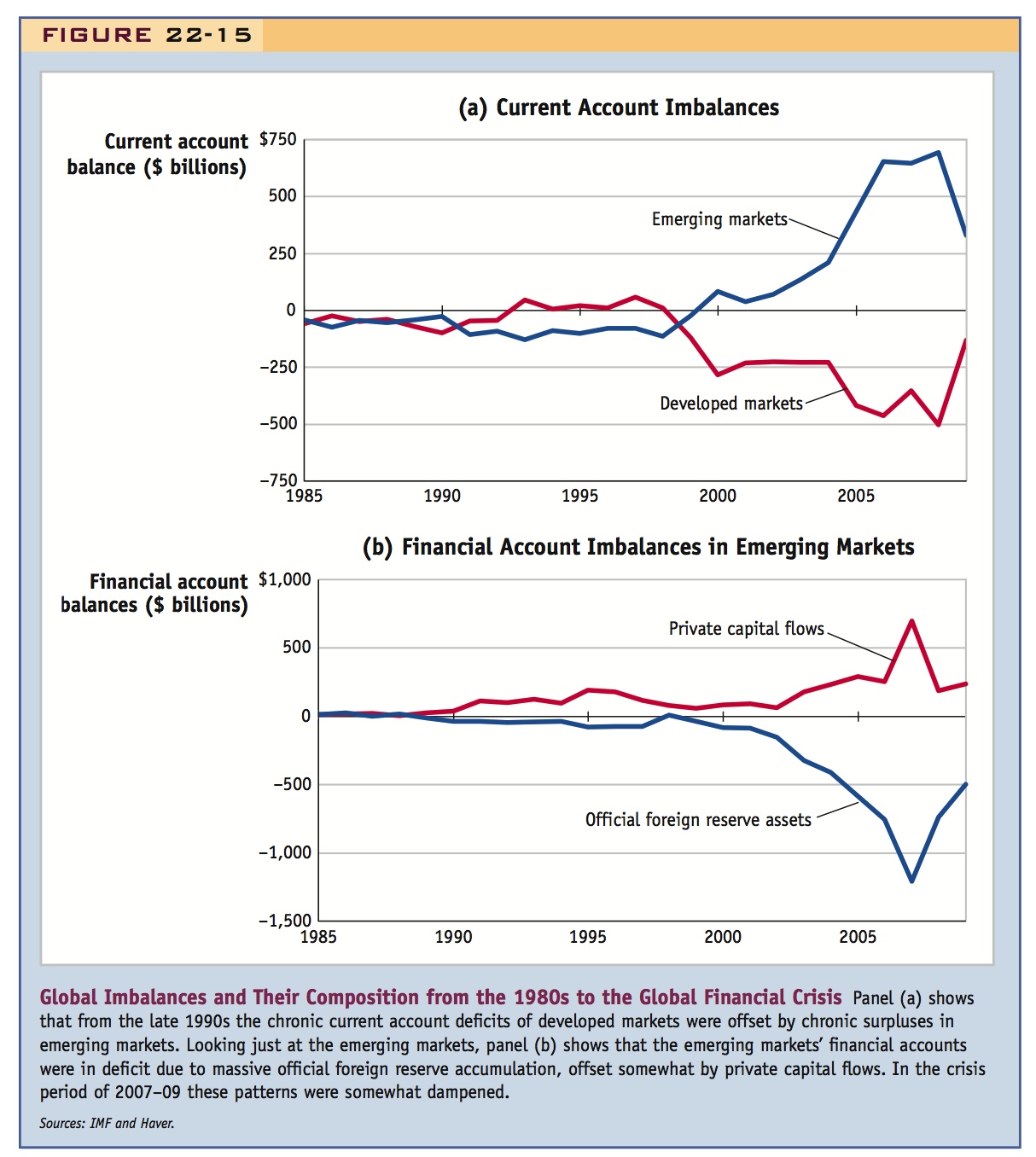

As we saw in the chapter on crises, a large source of global saving in the ten years prior to the crisis was the group of emerging market (EM) countries that consistently ran surpluses on their current accounts, as their investment rates (quite high) were consistently exceeded by their saving rates (even higher). Because the world as a whole has to have a current account equal to zero, these EM surpluses had to be offset by equal and opposite developed market (DM) current account deficits, as shown in Figure 22-15, panel (a). Given their sheer size, the largest surplus and deficit countries—China and the United States, respectively—often came to dominate the discussion, but when we adjust for country size, the trends were much broader than that. Most EMs ran significant current account surpluses (along with some DMs like Japan and Germany) and many DMs ran current account deficits of a size comparable to or exceeding those in the United States (e.g., the United Kingdom, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece).

Use this to review the U.S. CA deficit, and the effects of low world interest rates in the IS-LM-FX model.

This unusual situation soon drew the attention of economists and policy makers, and began to generate its own vocabulary. The unidirectional flow from EM to DM was referred to as the problem of global imbalances; the high level of savings in the EMs that was a part of it was referred to as the savings glut. Because real interest rates had fallen in this era, analysts recognized that even if the global level of savings supply and investment demand had risen in parallel, the fall in interest rates suggested that, on net, it was an increase in the supply of savings (relative to investment demand) that had upset the global equilibrium. What were the causes and consequences of this shift? To understand the causes, we need to assess policies in the EM economies where the flows originated; to grasp the consequences, we need to focus on the DM economies where the funds were put to use.

Remind students of the discussion of precautionary reserves accumulation and fear of floating.

On the EM side, at the broadest level, economists understand the dramatic increase in savings after 1997 as a conscious act of self-insurance. Many of these countries (especially those in Asia) had been very high saving societies for many, many years, and much of this was private saving. However, the new twist was the rapid increase in public (government) saving. As we saw in the balance of payments chapter, holding fixed private saving and investment, an increase in government saving necessarily sends the current account toward more surplus. Why did governments want to save? As we saw in the chapter on crises, and even in the introduction to macroeconomics, EM countries pay a high economic and political cost for crises. This outcome became painfully clear in the 1990s, starting with the Mexican crisis of 1994, but the lesson was rammed home by the chaos in Asian economies unleashed by the 1997 crisis, when currencies collapsed, deep recessions took hold, and governments were overturned when access to external financing dried up.

Looking back on those bleak times and on the inability of private capital markets or multilateral agencies such as the IMF to offer financial help that was both constructive and sufficient, many EM policy makers reached two key conclusions. First, they knew that they did not want to be the next Suharto, the Indonesian president humiliated by having to do the bidding of the IMF in exchange for funding; and they knew that to avoid being put in that position, they would have to take responsibility for their own financial security and, instead of relying on access to borrowed funds, would instead have to build up a war chest of liquid savings that could be drawn down in the event of a crisis.

496

The private sectors in EM countries also learned and made some changes to their behavior after the 1990s crises: for example, there was typically a shift toward less borrowing in foreign currency to reduce the liability dollarization problem that we noted in the chapter on global financialization as one of the peculiar risks for EM countries. However, EM policymakers first began a large, concerted accumulation of public external assets in their central bank or treasury accounts. That is, policymakers increased the purchase of official foreign assets as recorded in the Official Settlements Balance of the balance of payments (described in the first balance of payments chapter). In balance of payments terms, these large-scale imports of official assets by EMs were the Financial Account counterpart to their large Current Account (CA) surpluses, as seen in Figure 22-15, panel (b).

497

Review the discussion of the benefits of capital markets, and why capital should be flowing downhill.

Thus, official capital was flowing from EM to DM economies. Indeed, the official savings dwarfed the private sector capital flows that were generally moving in the opposite direction, from DM and into EM. On net, as some described it, capital was flowing uphill from poor to rich countries, an outcome viewed as odd by some observers because capital is generally expected to flow downhill from rich to poor countries, given the need for poor countries to invest in finance growth and economic development. As we saw in the chapter on the gains from financial globalization, economists have identified many reasons (summed up in the catch-all term “productivity”) to explain why capital might not flow from rich to poor countries. But there was a new development in the first decade of the new century: the flows had not simply stopped, they had reversed! As we have argued, however, this change might have been for good reason.

What impact did these flows have on the rich DM countries? First let us note that although the EM economies were largely engaged in the purchase of official assets like U.S. Treasuries, the effect of the massive purchase programs was felt in all credit markets. Buying a large amount of U.S. government debt bids down the yield on that debt (as the prices of the bonds are bid up). A result is that other holders of Treasuries now decide, on the margin, that they don’t find the asset so attractive anymore, and they seek higher returns from other assets. This change in portfolio balance lowers yields on other forms of debt such as corporate debt, loans, mortgages, and so on. This large flow of EM savings thus created a large wave of liquid funds in global capital markets seeking profitable investment opportunities, and allowing borrowers access to capital on some of the most generous terms that had been seen in a very long time.

On the face of it, access to a large flow of credit on extremely favorable terms sounds like a fantastically beneficial opportunity for the DM economies. However, behind that view is the assumption that given such an increase in economic opportunities, DM economies would use the funds wisely, with due regard to the risk and return on each project. In theory, good investments would be supported, and the benefits realized from those investments (the marginal product of capital) would be positive and high enough to exceed the real costs of borrowing. In other words, if the financial systems of the world, and particularly those in the DM economies, had been efficient in their allocation of such capital flows, and if all projects by private or public borrowers had been a wise use of funds, then all would have been well.

Depict the effects of this cheap credit on DM using IS-LM-FX. Have students think about the relevance of this cycle of booms and busts in EM for DMs.

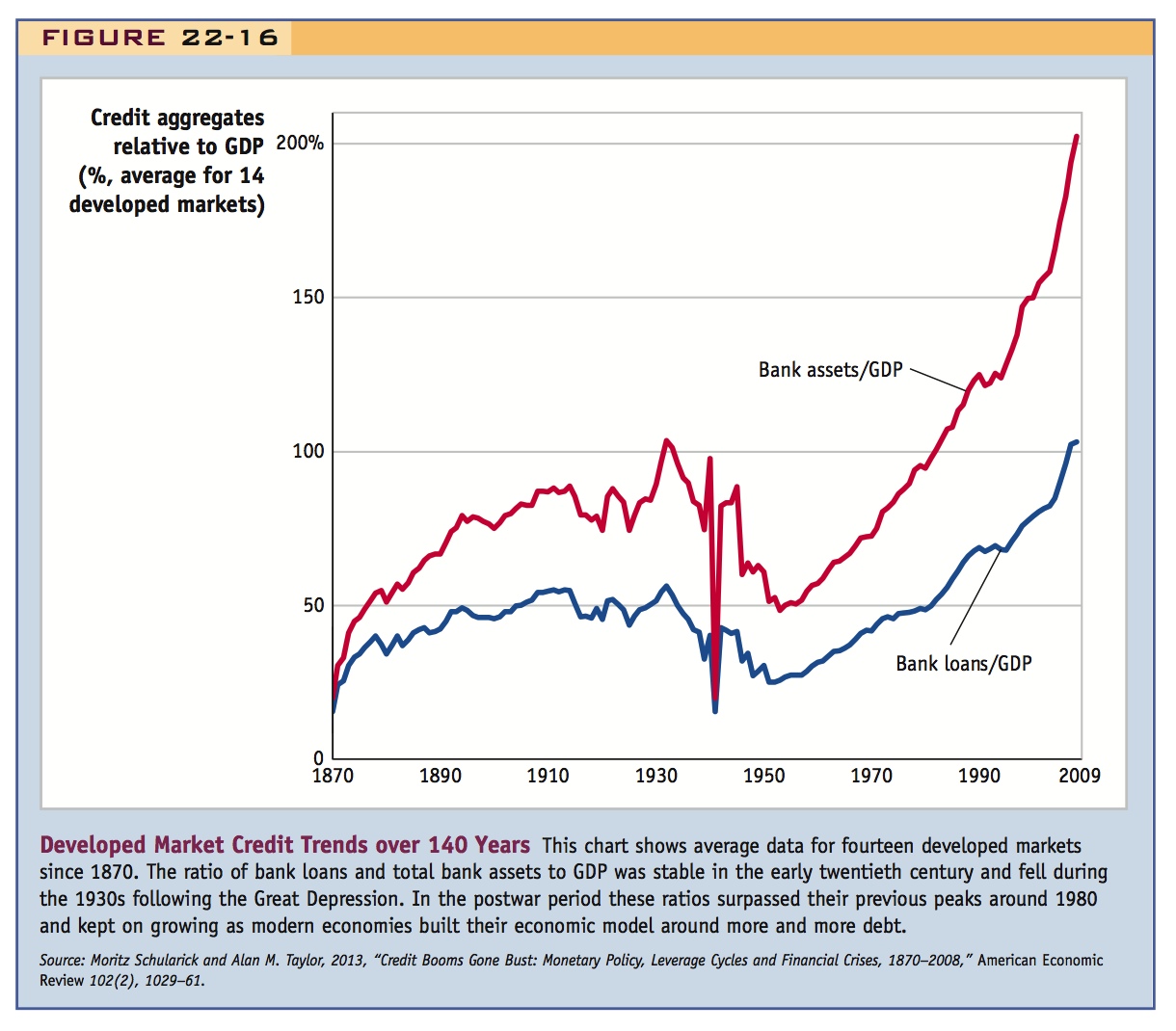

Unfortunately, such an outcome, often assumed in theory, is not guaranteed in practice. Many observers of emerging economies, and of the deeper history of the developed countries, were acutely aware of this possibility because they had seen repeated episodes of credit booms and busts that ended in tears for developing economies. These busts usually led to some combination of banking/currency/default crises, as we saw in the earlier chapters on crises. These observers saw that the DM countries now risked a similar fate, as the decade of the 2000s witnessed the expansion of credit in developed economies rise to a level not seen before in the entire recorded history of financial capitalism, as revealed by the trends shown in Figure 22-16.

Agreed. Use this to provoke discussion in class.

The view that the DM world could absorb these savings and put them to good use, and do so at ever higher levels of debt, depended on a particularly presumptive, some might say arrogant, view that despite the lessons from emerging economies, somehow the developed economies were “different.” The DM optimists’ argument could be summed up along the following lines: “Sure, those rather backward emerging countries with all their political problems and unsophisticated financial systems are inevitably going to have banking crises now and then and all the resulting problems, but we’ll never see that sort of thing here, because we are developed, and that sort of thing doesn’t happen to us anymore.” A period of relatively stable economic performance in the 1990s and early 2000s lent support to the claim that even if occasional financial shocks hit the economy, policy makers had developed the tools needed to contain such problems and ensure that this “Great Moderation” of the business cycle could continue. However, for a few skeptical observers (including, notably, some economists at the Bank for International Settlements), this attitude appeared overconfident, and it was soon exposed as such in a rather spectacular way.

498

Possibly assign teams to present each of these, and invite them to think of others.

Exacerbating Policies and Distortions The discussion of the longer-run forces behind capital flows from DM to EM countries provides a backdrop to the crisis, but as an explanation, it is incomplete. Many other questions remain. Why did these flows accelerate so rapidly in the years 2004 to 2007? Why did these capital flows result in such poor economic outcomes in places as diverse as the United States, Ireland, Latvia, or Greece? Was the problem generated by failures in economic policy making and regulation, or was it primarily a result of mistakes by market participants themselves? At the time of writing, these remain contested issues, but we can summarize some of the more influential and persuasive viewpoints.

499

Have them depict this, for both EMs and DMs, using IS-LM-FX.

Here too. Also invite debate about whether CBs should prick the bubble. Point out that this debate is very much alive right now.

This will provoke fierce debate among the students.

Discuss the argument for macroprudential objectives for the CBs, in addition to price stability and unemployment or income. . .

. . .as will this.

Assign chapters from Akerloff Shiller's "Animal Spirits," and possibly let students summarize them in class.

- Some observers believe that monetary policies in the EM economies, particularly China and other Asian economies, made the problem worse by pursuing a policy of deliberately undervalued exchange rates. This policy promoted an overly rapid, export-led growth strategy highly dependent on the Western (mainly U.S.) consumer being willing to go deeper into debt to purchase a growing supply of manufactured goods. However, it is hard to find robust evidence that, given their stage of development, these economies’ exchange rates were drastically out of line with normal historical or cross-country levels. These countries might just have been saving more for the precautionary reasons noted above.

- Some argue that much of the blame for the crisis resides with monetary policy makers in the DM economies, and especially the too-easy monetary policy of the U.S. Federal Reserve. These critics feel that under former Chairman Alan Greenspan, the Fed kept interest rates too low for too long in the period after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. These low interest rates encouraged lending across all credit markets at a time when the wave of savings from EMs hit the system, and facilitated bubbles at least in some places (e.g., the California and Florida housing markets). A similar argument can be leveled at the ECB, which also pursued rates that were “too low” for some euro member countries where similar bubbles were ignited (e.g., Ireland and Spain). However, it can be argued that the Fed was following its legal dual mandate of low inflation and high employment, with no sign of failure on either target. It can also be argued that, in theory, a low interest rate policy should not necessarily compromise a good financial system’s ability to do proper credit risk evaluation when properly regulated and left to itself.

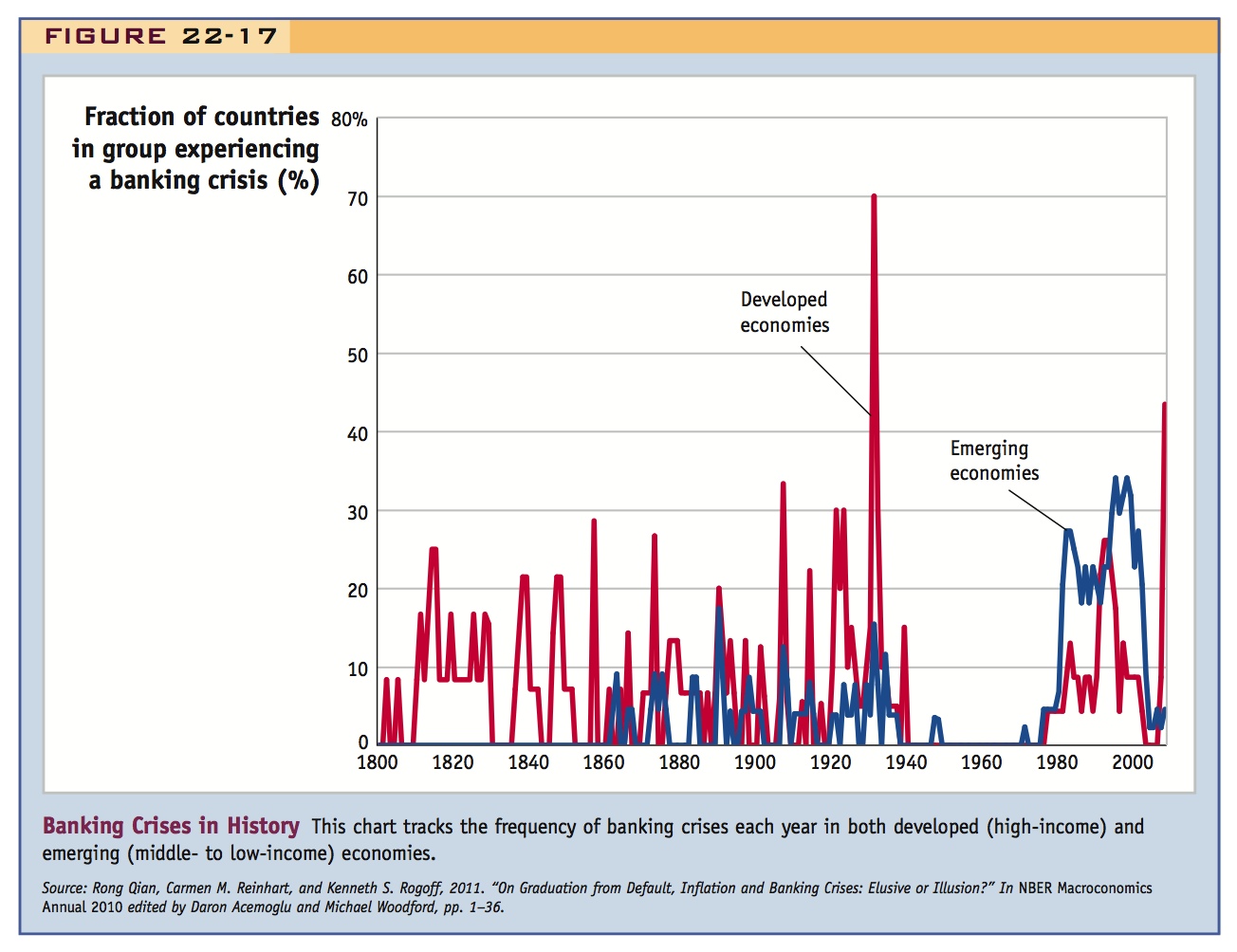

- Others would argue that the problem was a failure of regulation and supervision in that the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, and countless other central banks, as well as national regulatory bodies and lawmakers, simply allowed the financial systems to run out of control. This process had much deeper roots, going back to the trend toward financial deregulation seen around the world since the 1970s. This view is supported by the telling observation that under the more stringent regulatory regimes created after the 1930s disaster (e.g., legislation such as the U.S. Glass-Steagall Act, and more proactive regulators employing stricter standards), no developed country witnessed any banking crises whatsoever from 1945 to 1970. A slightly different take would argue that regulations did not shift, so much as they were simply outpaced by the scale of financial innovation, which both allowed the system to take on greater risks through new products (e.g., the securitization of credit with a reliance on rating agencies and the use of unregulated derivatives) and to expand so much as to create large, complex, “too big to fail” (or in some countries “too big to save”) banks. Either way, regulators share some of the blame either for relaxing rules too much or not keeping up with the times.

- Some analysts believe that government failure is to blame because governments distorted private incentives in various ways, over and above any impact of easy monetary policies noted above. For example, in the United States, the government gave implicit backing to quasi-official organizations like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which purchased or guaranteed large shares of the mortgage market, and ended up effectively bankrupt. The government was also seen as offering implicit backstops to many “too big to fail” banks. When this happens, the implicit insurance gives people an incentive to take too much risk, knowing that they will be bailed out of some or all losses, a problem known as moral hazard. Similar concerns arose about European banks, which in some countries were larger than those in the United States, and even more leveraged when the crisis struck. In addition, the central banks stood accused of offering some kind of similar downside protection, by seeming to declare, when asked, that their doctrine concerning asset price bubbles was not to pop them or lean against them, but rather to wait for them to collapse and then step in to fix any problems. Yet against these points, it could be noted that large swathes of credit market excess—indeed, the majority—flowed through channels quite distant from the government’s reach, and that ex post, whatever the perceived bailouts the bankers thought they might get, in practice most of those exposed found themselves with a lot of “skin in the game,” of which they lost a great deal (or, in the case of Lehman Brothers and many other entities around the world, almost all of it).

- Many other observers see widespread evidence of market failure, in which irrational investors, herding, imperfect information, and asymmetric information all created serious inefficiencies in financial systems. According to this view, which is hundreds of years old, the financial markets are capable of sustained bouts of euphoria followed by revulsion, a kind of mood swing where investors switch from being willing to take on lots of risk, only to then switch quickly to avoid the same risks, an oscillation between greed and fear that has no real connection to market fundamentals and that creates unnecessary and unwelcome volatility in the economy. Yet even if this view often looks persuasive after the fact, spotting the bubble or the imminent crisis beforehand is a very different matter: even if we can now agree that there was a U.S. housing bubble, as it unfolded, it took an awfully long time for more than just a few observers to voice their concerns.

Summary History shows that economies based on financial capitalism have experienced banking crises throughout the modern era. This is true whether one is speaking of developed markets or emerging markets, with the possible exception of a brief interlude of calm during the financially repressed post-1945 era, as shown in Figure 22-17. However, as the financial sector was deregulated in the last three or four decades, it regrouped and expanded, and we have once again found ourselves in what is, to the economic historian, if not the economist, a very familiar place characterized by periodic episodes of financial instability. With some success, policy makers mitigated some of these shocks, but after credit and leverage grew to unprecedented levels, there came a shock so large that it defied control and sent the world economy into the most severe slump since the 1930s Great Depression.

Panic and the Great Recession

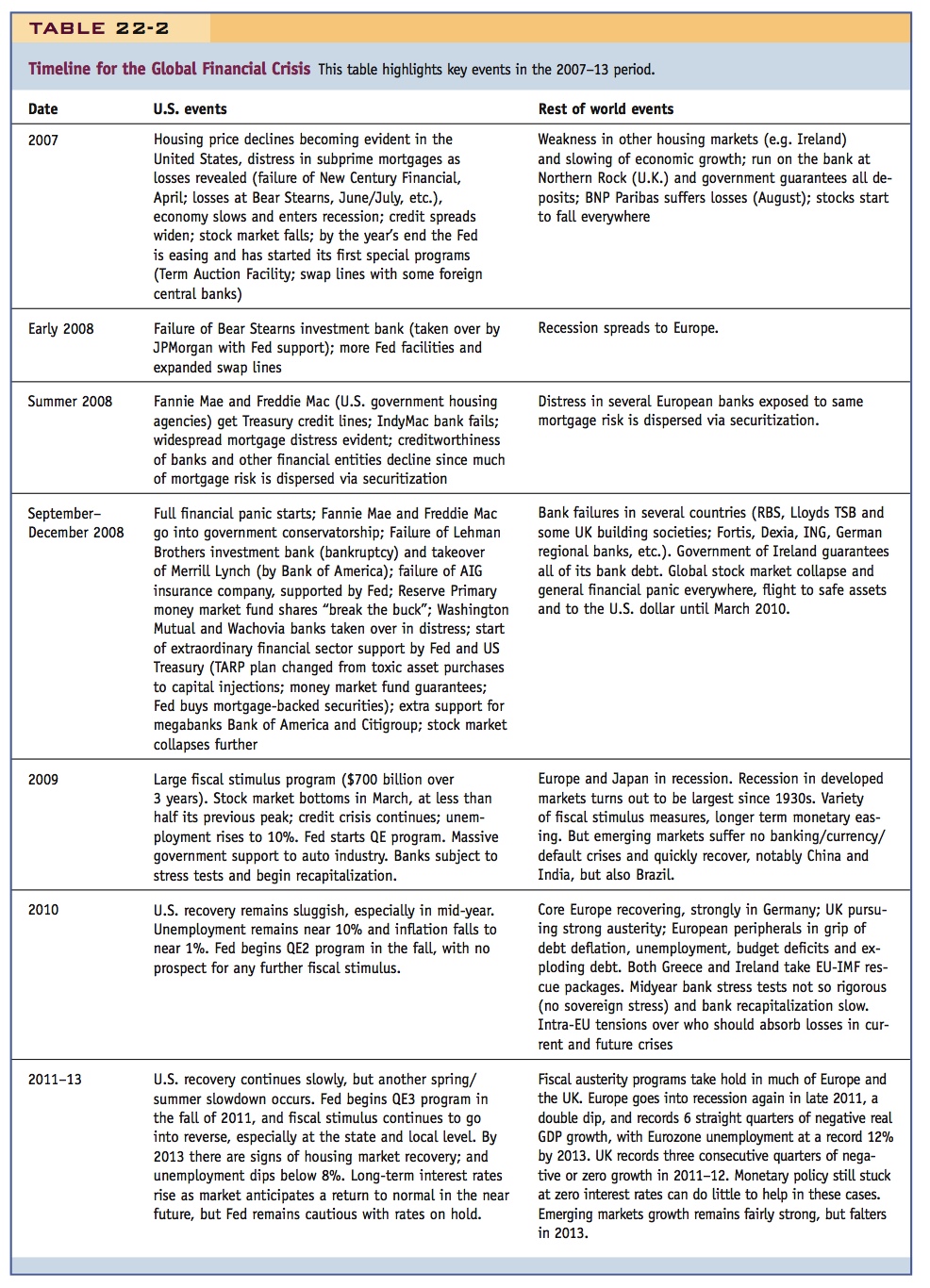

In 2007 the Global Financial Crisis started to unfold quickly from a set of potential risks into a massive catastrophe that would wreak havoc on the global economy for the next several years (see the timeline in Table 22-2).

501

Like almost all financial crashes seen over the course of modern economic history, some particular event triggered a flight from risk to safety in capital markets. In this case, the trigger was a deterioration in the quality of U.S. residential mortgages. As house prices stalled, and then fell, and mortgage delinquencies rose in 2006 and 2007, problems quickly became evident, especially in the more risky subprime mortgages. Similar stresses also erupted in the financial and housing markets in other countries such as the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The losses were centered on major financial institutions in the United States and overseas including commercial banks (some of the very largest like Citibank or Bank of America in the United States, and RBS in the United Kingdom), investment banks (which held some of the mortgage risk), and insurance companies (like AIG, which had provided lucrative but ultimately underpriced default insurance policies on many mortgage products that it was ill-equipped to honor).

Ask students to compare and contrast this with other bank runs they encountered in this book.

A Very Modern Bank Run Once the problems of bad mortgages had spread, and given the very thin (some would later say, too thin) capitalization of the financial system in general, it became very difficult not only for outsiders to borrow from banks, but also for banks to borrow from outsiders and from each other. People feared that banks might end up unable to repay their loans. With one or two exceptions, deposit runs were mostly avoided thanks to deposit insurance. But in today’s economy banks also fund themselves by short-term loans, and it was these funding facilities that shrank in size, or became prohibitively expensive, when the creditworthiness of banks came into question.

502

503

This inability to borrow had the same effect as a run on deposits: banks had to shrink their balance sheets and scramble for liquid funds to fill the funding gap left by their inability to borrow. To free up and conserve cash, they had to stop making new loans and/or allow old loans to “roll off” their books. They also had to sell their securities starting with the most liquid, but as the crisis took its toll, they then had to sell more illiquid assets (such as hard-to-value mortgages and derivatives) into collapsing markets at what would later turn out to have been “fire sale” prices precipitated by the usual lack of buyers in a panic. Because the banks were taking steep losses not only on their loan books but also now on securities, their capital was soon depleted. As their share values fell, many banks were on the edge of bankruptcy. Several huge banks, including the investment banks Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers and retail banks such as Washington Mutual, either failed outright or were bought in a takeover for pennies. In September 2008 the financial systems in the United States and all over the world were plagued with a banking panic of a magnitude not seen since the early 1930s.

Mention Bernanke's work on this, as well as on the Depression, both of which affected his response to the crisis.

Financial Decelerators As always, the financial crisis had the effect of depressing real economic activity, through the so-called financial accelerator mechanism (or in this case, decelerator). Much of business depends on a reliable financial system to fund day-to-day activities and the massive problems in the financial system added a real friction to the economy. Also, when wealth is destroyed by a panic, the impaired households and firms tend to rebuild their wealth by saving to pay off liabilities or accumulate assets, thus dampening the demand for goods and services. Lost wealth also impedes access to credit, making recovery slower than it otherwise would be. In 2008 and 2009 there was also policy uncertainty as authorities in the United States and throughout the world tried to devise a sequence of monetary, financial, and fiscal policies to stem the crisis.

A curious side effect of the crisis was the effect on the dollar and the unusually high spread between U.S. government interest rates and private sector interest rates: at the height of panic, investors sought out U.S. dollar assets as a safe haven (a typical experience for a reserve currency). This caused the dollar to appreciate markedly and the yields on U.S. government bills to approach zero. That is to say, risk premiums became a factor in all currency and asset markets, not just in emerging countries, and these forces rather than, say, policy interest rates, became for a while the major drivers of market rates and currency values.

Have students explain these policies using IS-LM-FX; add the liquidity trap and possibly interest inelastic investment. Talk about QE.

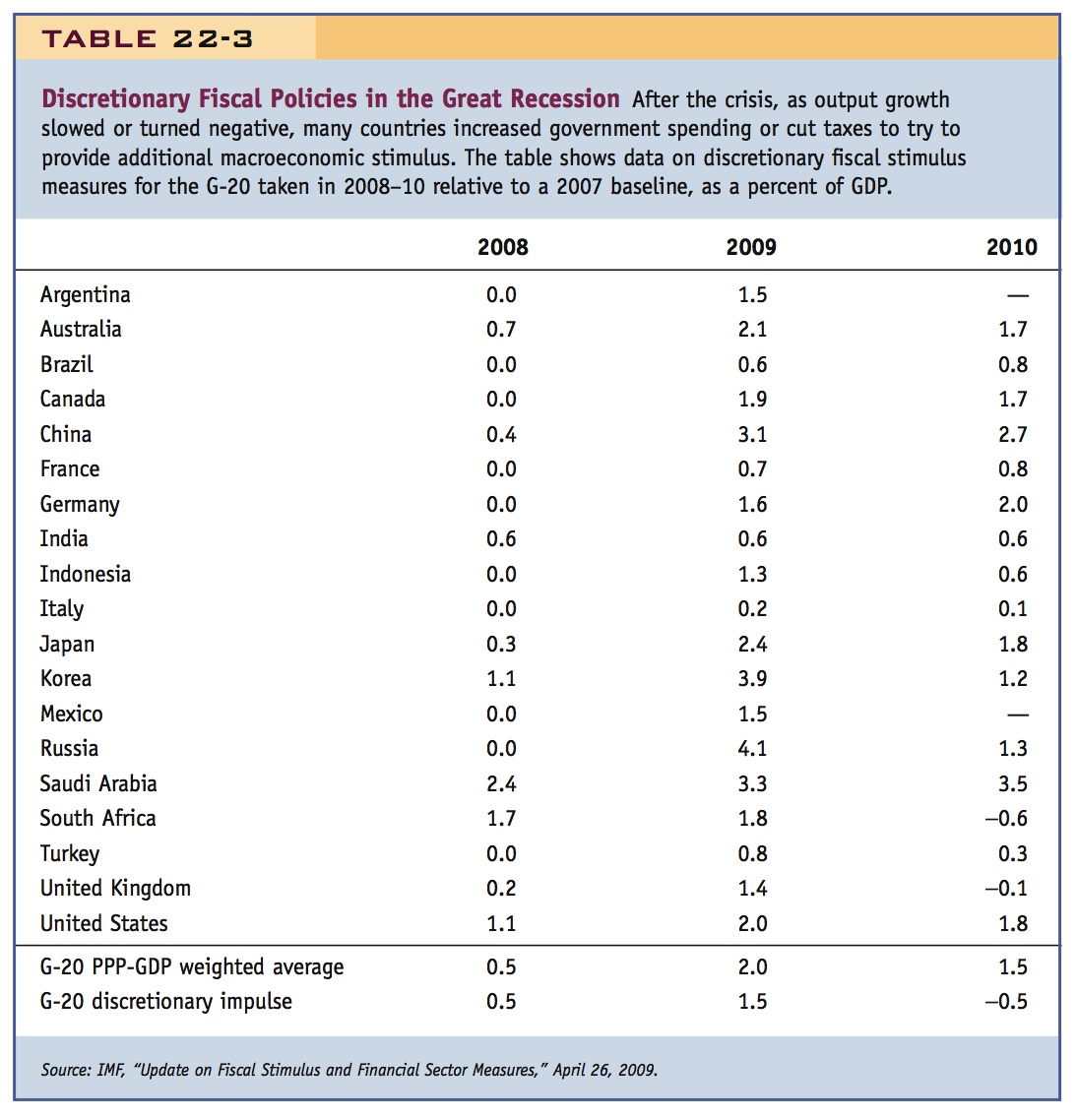

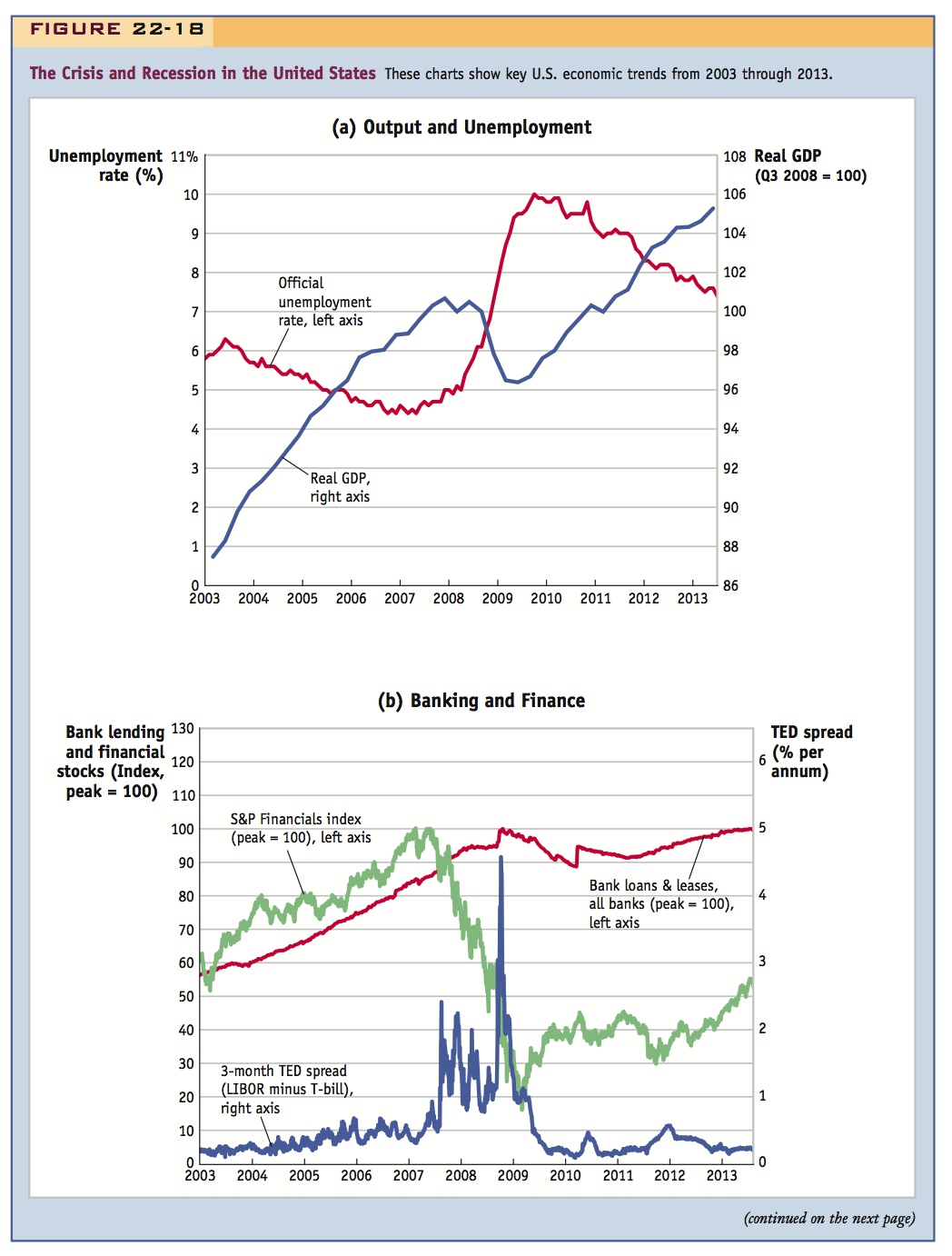

The End of the World Was Nigh It took until March 2009 for the collapse of U.S. stock markets to end (the S&P 500 Index hit a low point of 666). By this time three of the big five U.S. specialist investment banks had failed or been taken over and a $700 billion bank recapitalization scheme had been created by the U.S. Treasury in fits and starts during the last days of the Bush administration and the first days of the Obama administration. Confidence in the ability of the economic and financial situation to recover was low, to put it mildly. Bank recapitalization projects took shape in other countries, too (the United Kingdom took the lead on this front), and a greater sense of calm was restored by the April 2009 G-20 summit in London, at which a united front of global leaders pledged greater support and cooperation. Fiscal policy makers had by then stepped in with large-scale stimulus plans in most countries (see Table 22-3) and monetary policy had been eased everywhere, in many countries all the way down to zero interest rates. Credit was still tight, but for those who could get it, costs had fallen. Despite fears of a return to 1930s-style protectionism, world trade policies stayed open, thanks in part to countries’ commitments to and oversight by the World Trade Organization, and trade volumes started to pick up.

504

As these efforts took hold, the freefall of the world economy halted, and the sharp downward trends in GDP and trade (similar to those seen after 1929) hit bottom. But by now the economic costs of the financial meltdown had reached unfathomable heights (see Figure 22-18 for U.S. evidence).

Despite initial concerns, it was not the actual direct costs of financial bailouts that were the main problem. In the United States, the terms obtained in the depths of the crisis were so favorable that taxpayers made a small profit; in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, and especially Ireland, the costs to the public purse of bailing out the banks were huge. Instead, the main problem was that in the United States and elsewhere output was 5% or more below capacity and unemployment near to or above 10%, conditions that were likely to persist for years. In terms of lost output and employment, this was the worst U.S. and global slump in 80 years. In terms of the massive lost tax revenues for governments, along with some much smaller increases in spending, this event blew a large hole in the fiscal stability of many developed countries that is likely to last for decades. In some countries the economic crisis has brought into question the solvency of the government itself. Thus, as history has shown time and again, a banking crisis can quickly mutate into a sovereign debt crisis as governments, to try to prop up the system, socialize the losses of the financial system at significant fiscal cost.

505

506

Talk about hysteresis and the secular stagnation argument.

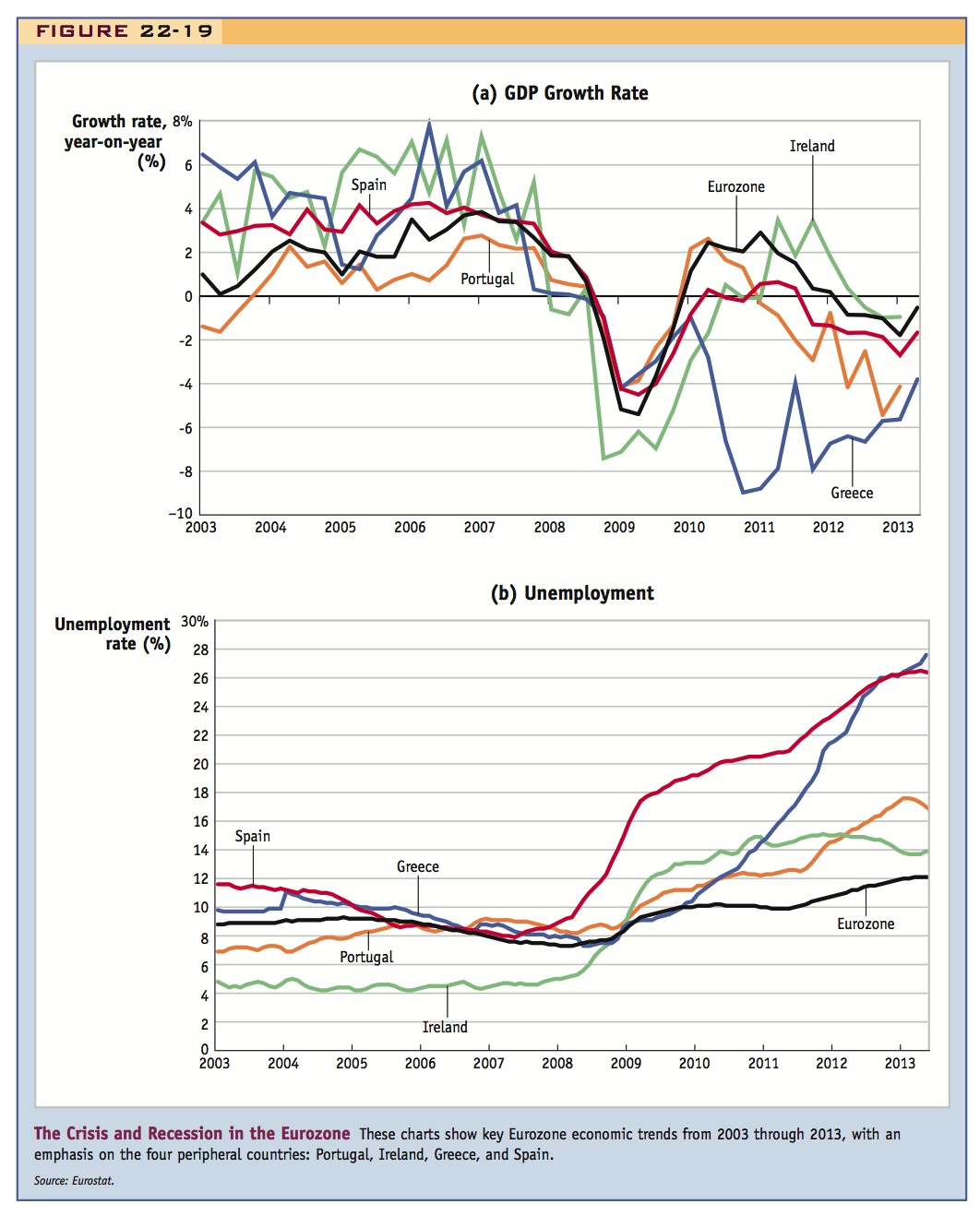

Europe As the crisis wore on, and recovery started, the full extent of the shock and the policy responses varied in different countries. One of the most striking examples of divergence was the experience of the Eurozone during this episode. The traditional core countries of the Eurozone, especially Germany, managed to escape quite lightly, even though their banking systems had been infected by U.S. toxic assets. Deep trouble was brewing on the periphery of Europe, however (see Figure 22-19).

In Ireland large property booms went bust and the banking system was at risk of collapse. All these potential losses were rather hastily absorbed by the government in September 2008, but their eventual size grew to about half of GDP in late 2010 and the necessary fiscal adjustment, already austere, had to be tightened even further. Despite these efforts, Ireland was seen by markets to be at an elevated risk of default. The use of monetary policy to boost the economy was not an option: the Irish had joined the euro and could pull no policy lever but the one marked “fiscal,” which was hard in reverse. By 2009 real GDP had fallen by 13% from its 2007 peak and unemployment had risen dramatically; even in 2013 output was still 10% below peak as the depression dragged on.

507

508

Similar forces were at work in places as far afield as the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Greece, and Spain and Portugal. Although the Baltics still had their own currencies, they chose not to break their peg to the euro and suffered greatly as a result. Spain had a housing boom and bust, but fortunately, it was less extreme than Ireland’s. Less exposed to a housing meltdown and domestic banking crisis, the less-developed economies of Portugal and Greece faced the more traditional problem of a chronically large budget deficit that blew out to a massive gap in 2009 and 2010 once recessions caused tax revenues to evaporate. Greece faced an additional and long-standing credibility problem as a result of reporting falsified economic data that disguised its true problems.

Even though the cause of their fiscal disasters was different, however, Portugal and Greece were lumped together with Ireland and Spain in the uncharitably named “PIGS” group, and given low (near-junk) credit ratings. By 2010 this group had access to financial markets, if at all, only at very high interest rates. They skirted very close to insolvency and had avoided default only through funds advanced by the ECB, the EU, and the IMF (the “troika”).

In March 2010, for example, Greece needed a special EU-IMF loan rescue package. But this only staved off the problems for a while. By October 2010 the peripherals were facing punitive market interest rates, and in November the Irish government was persuaded to follow Greece into a very contentious EU-IMF loan rescue package to allow it to pay off (at taxpayer expense) the vast losses of its banks. Portugal would end up needing a similar program. Eventually, even under the terms of the new Greek program, the debt burden remained too high and Greece defaulted and restructured its debts in 2012, to lower the debt burden (by this time most of the debt was in official, not private, hands). Again, peripheral countries like Spain and, more important, Italy came under funding pressure, which was only relieved when new ECB President Mario Draghi said “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” which has been interpreted to mean that the ECB will step in to prevent further sovereign crises, a belief which thus far has been self-reinforcing and not tested.

However, much Greek debt was held by banks in Cyprus, and with the banks’ solvency in question a bank run developed there slowly at first then building up to a massive crisis in early 2013. Cyprus’s government and the troika then imposed capital controls, suspended bank withdrawals, and imposed losses on large depositors and other bank creditors. Cyprus was de facto outside the Eurozone and the problem of how to resolve failed banks in a monetary union without a fiscal or banking union was brought to the fore.

Relate this to the earlier discussions of fixed versus flexible rates and the euro.

Needless to say, this debacle exposed the difficulties of how to regulate cross-border banking and finance within Europe, and, most serious of all, raised many questions about the long-term viability of the euro project (as we saw in the chapter on the euro). For example: What, if anything, should be done about Eurozone fiscal policy rules after the spectacular failure of previous efforts? Is it possible for such disparate economies to be safely put into a common currency given the asymmetric shocks they face? Can a way be found for European cross-border banks to operate safely? How can the “global imbalance” problem within the Eurozone microcosm be resolved to temper the flow of capital from sober and restrained high-savers in Germany and elsewhere to persistent-deficit, credit-bubble, and crisis-prone low-saving peripheral countries? Can the Eurozone tolerate a default by either a state or a banking system, or will moral hazard prevail? Will the ECB be left to pick up the bill? Or will it be the taxpayers, and if so, which ones? The resolution of these Eurozone problems may require shifts to greater banking, fiscal, or even political union, but as of now any meaningful steps in these various directions have yet to appear.

509

The Rest of the World What about the rest of the world? Outside of the United States and the Eurozone, the impacts were less catastrophic. Japan escaped lightly for the rather depressing reason that its economy had already been in a quasi-slump for over 15 years, had already seen its banking system collapse, and had very slow growth and near-zero rates of inflation and interest.

The most remarkable outcome was, however, in the emerging market world where rapid growth quickly resumed. These countries had experienced strong precrisis economic growth, were not exposed so much to financial sector risk at home (or to problems in the developed market’s financial world), carried less debt in their economies, and had also amassed large war chests of reserves. In many cases, these nations spent their reserves to support fiscal policy expansions that buffered their economies from the global shock, without necessitating new borrowing (when credit markets were impaired) or placing their exchange rate regimes at risk. These nations had saved for a rainy day, and now it was pouring.

The main locus of this rapid EM recovery was in Asia (except for Japan), which was buttressed by strong support measures in China, including a large-scale public spending program. Latin America also turned around very quickly, led by boom conditions in Brazil and deft deployment of reserves in Chile. Only Mexico, more closely tied to the economic disaster in the United States, had to contend with macroeconomic difficulties. The luck of Brazil, as a commodity exporter, was also shared by a few DM countries, like Australia, Canada, and Norway, whose valuable natural resources were quickly in demand again after the resumption of growth in China and other EM countries.

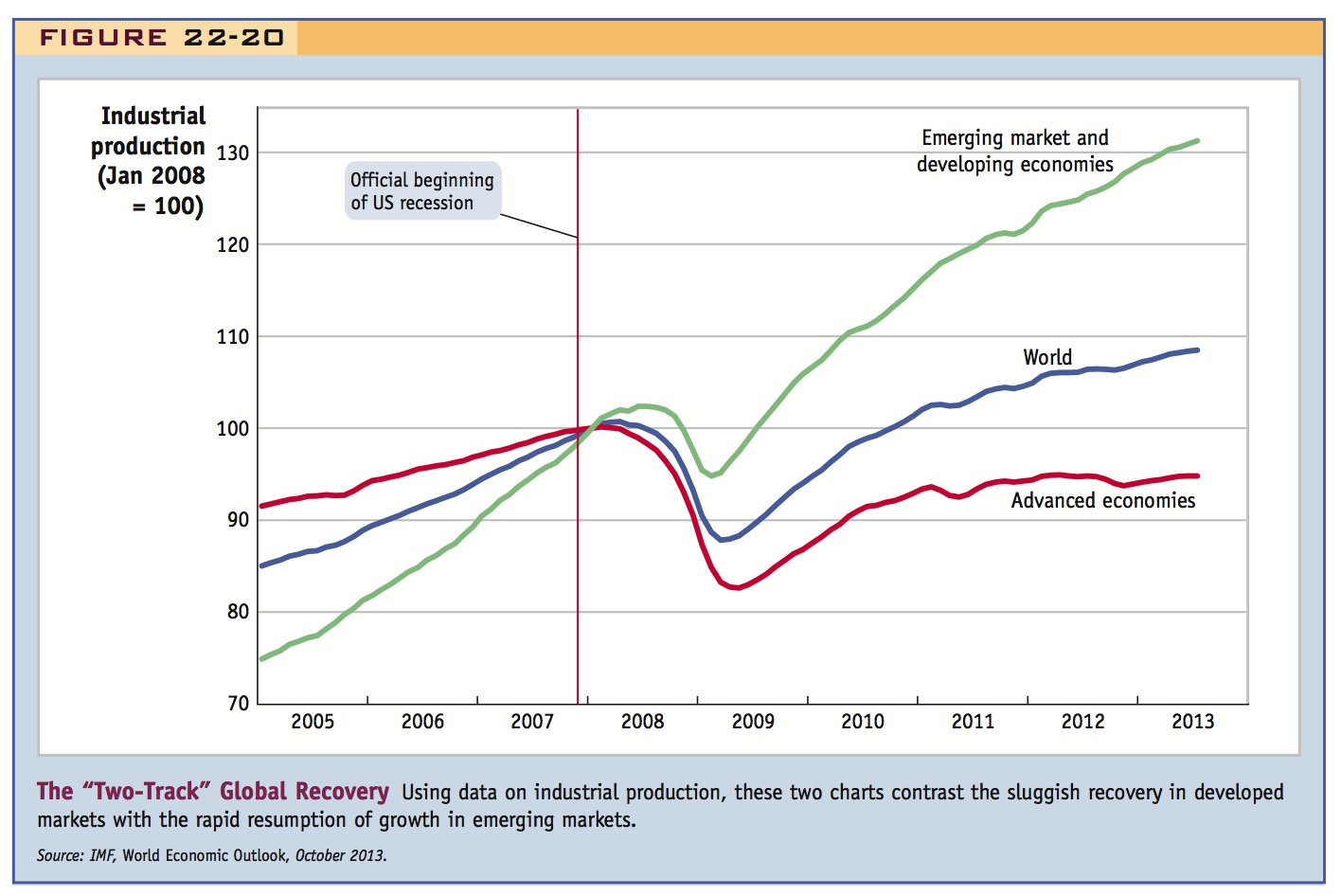

In this way, a remarkable “two-track” economic recovery started to take shape in 2009 (see Figure 22-20). It was something never witnessed before: the DM countries were unable to kick start a true recovery, but the EM countries powered ahead regardless, largely under their own steam. The “decoupling” of the EM fate from the DM trend was unusual. From a historical point of view, however, it was even more striking that the world had gone through its greatest synchronized global financial crisis ever and not a single EM country had experienced a banking, currency, or sovereign default crisis. Had anyone suggested this outcome before the fact, they would surely have been greeted with incredulity.

Here too, assign teams to explain each of these points.

The Road to Recovery The question going forward is how long this state of affairs can persist. When, if ever, will the DM countries, and especially the United States and the Eurozone, return to “normal” (whatever that means)? As of late 2013, the U.S. recovery was further along, with output creeping above its previous peak; but Europe and the U.K. remained stuck in deep depressions exceeded in severity only by the downturns of the 1930s. Several risks (some of them remote) still lurked in the background:

Try to depict how QE might affect things in the IS-LM-FX story.

- In most DM countries, fiscal policies were tightened in 2010 and later years, via the withdrawal of U.S. fiscal stimulus, or as part of U.K. and European austerity programs. There were also sequestrations and government shutdowns in the United States. Countries tightened in peripheral Europe, when they were forced to do so by the troika after they could not borrow in markets, but for others it was a choice, as in core Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States. Critics argued that austerity slowed growth and exacerbated public debt levels.

- Monetary policy had hit the zero interest rate lower bound at the Fed and other central banks. This left no further room for easing using conventional tools when such easing was badly needed (especially when fiscal stimulus started to be withdrawn in conditions of still-high unemployment and below-target inflation). In addition, the conventional transmission mechanisms through which monetary policy affects economic activity remained impaired as many banks continued to struggle with damaged balance sheets. Many small and medium-size firms were unable to borrow at low rates. Many households held little or negative equity in their homes and were unable to borrow or refinance at low rates.

- The Fed had instituted unconventional measures such as quantitative easing (QE) used in the crisis and QE2 and QE3, additional rounds undertaken in 2010 and 2012, causing the Fed’s balance sheet to expand. These unsterilized large-scale asset purchases could provide stimulus through a variety of channels to lower interest rates throughout the market, support asset prices and wealth, and also weaken the U.S. dollar. The latter effect was not always welcomed by trading partners and has sparked concerns of a global “currency war” that could then mutate into a protectionist battle or trade war. And supporting asset markets in such an open and sustained way marked a controversial new step for the Fed.

- How the Fed or Bank of England or Bank of Japan would exit from QE-type measures and how the ECB would pull back its special liquidity support and (sterilized) bond purchase programs are, as of late 2013, future problems still to be resolved. Can these steps be taken without igniting inflation if liquidity isn’t contracted sharply enough? Can they be done without sparking bankruptcies or defaults if interest rates rise too quickly and hurt those on floating interest rates? It is hard to find precedents for these unusual monetary experiments, and even a hint of the Fed scaling back its QE program spooked markets in mid-2013.

- As of 2013, the Eurozone remained in a fragile state: growth was dismal, with weak banks and fiscal positions, especially in the periphery. There was still no grand strategy apart from liquidity provided by the ECB. Fiscal austerity continued to bite, especially in the periphery as a required condition of the bailout programs. Greece’s debt levels continued to climb into unsustainable ranges, making a second default more likely. Europe’s new European Stability Mechanism cannot be used for legacy problems, but even going forward it would be too small to cope with crises in multiple countries all at once. Beyond this scheme no larger or more permanent arrangements to handle Eurozone financial instability and sovereign crises had yet been determined.

- Almost all of the advanced economies emerged from the crisis with still historically high private debit levels (debts of households and firms) as well as rapidly rising public debt levels. The emerging countries grew more strongly, with less fiscal strain, but on the back of rapid private credit growth of their own. By 2013 even that engine of growth was faltering. How much this burden of public and private debt will continue to weigh on DM and EM prospects for future economic growth and complete global recovery remains unclear, but such levels have not been seen before. Here again, we are in uncharted waters and economic research is active in these areas.

We should hope that the world will discover how or if some of the conditions that helped shape the crisis might be avoided in the future. Can better financial regulation prevent damaging credit booms? Can improved bankruptcy procedures help countries deal with failing banks quickly and with less damage to the economy or the taxpayer? Can more EM economies find alternative insurance mechanisms, or else accumulate an adequate level of reserves? Can the Eurozone develop a more stable political and economic architecture than the half-built structure currently in place? Will global imbalances persist at the levels seen in the last decade, or will they moderate either through smooth market adjustments, or in response to more direct policy activism?

Conclusion: Lessons for Macroeconomics

The crisis is still not over, and it will take a long time to assess its consequences. However, it is already affecting the way we study macroeconomics: (1) It is highlighting the defects of some standard models: We can’t focus on the real side of the economy and ignore the financial sector; we need to re-integrate money and banking into our macro models; we need to focus on how the demands for money and financial assets change in time of crisis; we need to incorporate irrational herding, limits to arbitrage, moral hazard and imperfect information. (2) Policy needs to be reconsidered: Should central banks be concerned about financial stability as well as price stability and full employment? Should they focus narrowly upon interest rate policy, or should they shoulder broader macro-prudential goals? (3) Arguably, we wouldn’t have been quite so surprised by the crisis if we had paid greater attention to its historical precedents. Perhaps economists should reacquaint themselves with history.

The above description of the global financial crisis and its aftermath is necessarily incomplete. The event itself is far from over, and it represents a massive shock to the world economy, both economically and politically. Its full repercussions will unfold over many years and are impossible to predict with certainty.

Use these assertions to provoke debate, about the crisis itself, and more broadly about the implications of the crisis for how we do economics.

What is more certain is that the crisis is already causing serious intellectual repercussions and is profoundly changing our thinking with respect to the way that macroeconomists do their research and teaching. It is now clear that many defects of existing, standard macroeconomic models need to be fixed. It is not enough to model the real side of the economy and ignore the financial sector. Deeper thinking will be needed to integrate finance and macroeconomics and to modernize the neglected area of money and banking, once a core subject of macroeconomics. In this respect, economists will need to think carefully about what drives the demand for money and other safe assets when markets fail, and how to understand and incorporate rival views of crises, such as irrational herding, limits to arbitrage, imperfect information, moral hazard, and so forth.

512

The scope of policy objectives will have to be carefully scrutinized to determine whether and how the authorities can develop sufficient (and sufficiently sharp) instruments to meet their targets of not just price stability and, possibly, maximum employment, but also financial stability (an original, but somewhat forgotten, responsibility of central banks). Here, a narrow focus on interest rate policy will be joined by a broader investigation of what a sensible macroprudential policy for the financial sector might look like.

Lastly, the challenges will require new evidence to guide theory and refute or confirm hypotheses. Financial shocks of the kind we have just witnessed are rare events. For the purposes of empirical study, a sample of comparable episodes can be found, but only if one looks deep into economic history. The calm and prosperity of the world economy from the mid-1980s up to 2007, the so-called Great Moderation, lulled many into thinking that we had entered a new era, in which “this time is different”; it turned out to be an illusion. Greater attention to the lessons of economic history might have counteracted some of that complacent and naïve thinking. In the end, economists and policy makers face the task of better linking aggregate economic outcomes to financial conditions, a task that will surely take economic research down some new and interesting paths. There is much work to do.